Margarita V. Beltrán: Arder la casa

Margarita V. Beltrán’s piercing photo essay Arder la casa is a powerful exploration of her family’s hidden history and its deep entanglement with the tumultuous political landscape of Colombia. Throughout the project, fire acts as a revelatory — and indeed revolutionary — force, revealing hidden aspects of her family’s past as well as Colombia’s national mythologies, realities, and collective traumas. When viewed through a broader lens, Beltrán’s compelling photo essay offers a poignant portrayal of the far-reaching repercussions stemming from six decades of Colombian armed conflict and political unrest. Presently, over half a million Colombians have sought refuge in exile, driven by the desperate quest for safety. Regrettably, a significant portion of these exiles are forced to escape and live in concealment due to the constant threat of violence and persecution. Beltrán’s photographs do more than just make visible this anonymity. They function as a universal mirror, revealing the survival strategies and identity transformations of not only thousands of those who depart but also of those who are left behind navigating the complexities of fragmented bonds, memories, geographies, and timelines.

Arder la casa

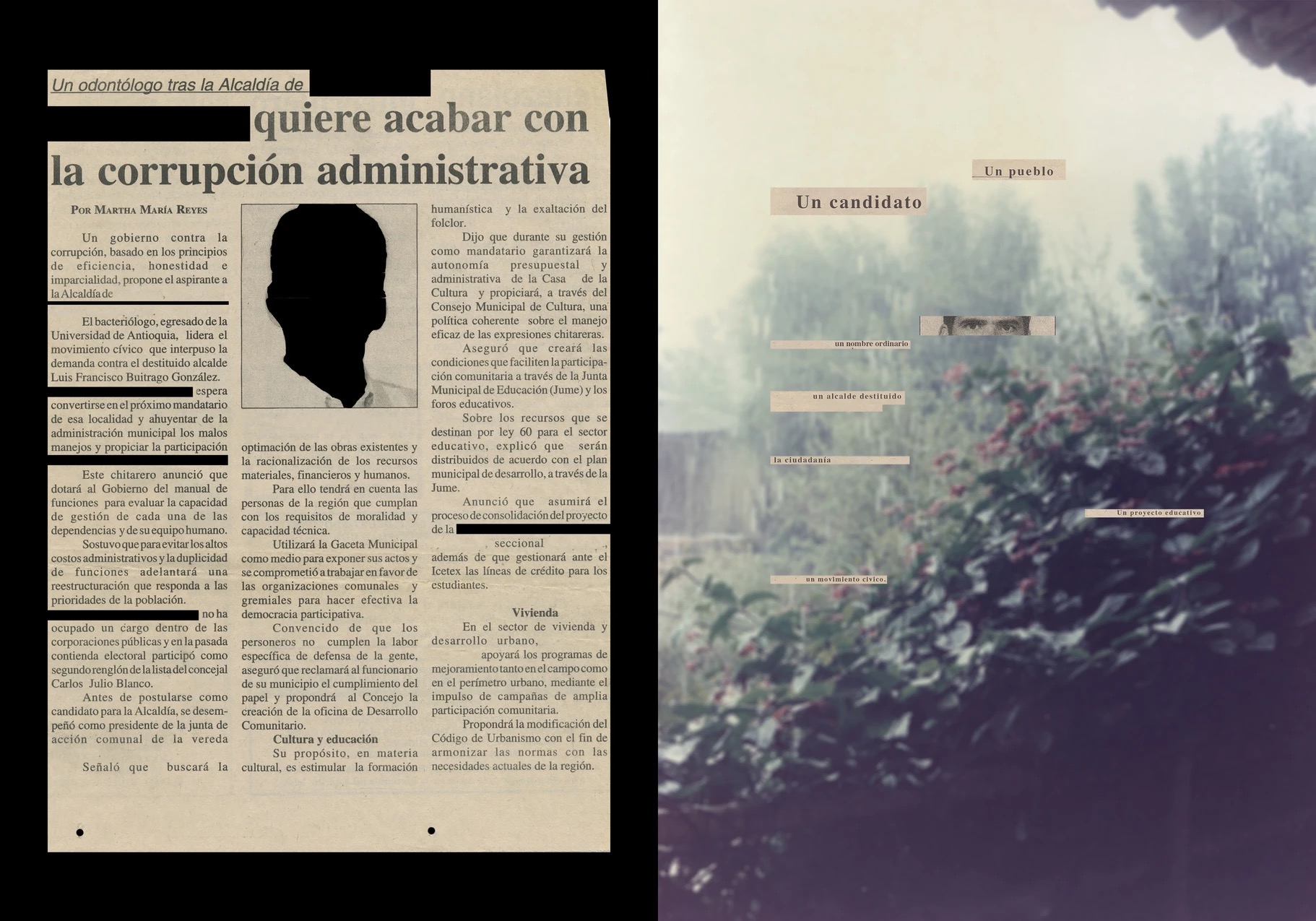

Fictions constructed to protect, hide or to forget. National myths that become inseparable from personal memories, flooding family albums and burning child fantasies. I can think about the globality of certain tropes as the one of the hero, that same one that attempted to be a father but decided for a public life. This project, Arder la casa, explores the contingencies of political violence in Colombia through my family history and my father’s exile. In 2015, after finishing his term as mayor of a small town bordering Venezuela, my papa crossed the Colombian border — fleeing the political persecution he had been subjected to for decades. I remember him disappearing on different occasions when I was still a child. But fairy tales that my parents told me justified his absence. Now, for the first time, I could understand my family was fragmented and separated in the harshness of a country where political violence reaches the worst statistics in the world. Witchcraft, religion, socialism, and mafia culture are at play within the cultural environment of the story. My father’s exile marks an inflection point from which the project develops. Traveling between past, present, and future, I unveil our history to reveal traces of violence, separation, and cyclical escapes. The project utilizes archives such as pictures or newspaper clippings, paintings, analog photography, video, and sculpture.

Margarita V. Beltran (she/her) is a Colombian lens based artist based in between Berlin and Colombia. For a number of years, Margarita has worked on gender, race, and political violence in the context of Colombia and Germany. One of her most recent projects, Arder la casa, has been on display at the Michael Horbach Stiftung in Cologne, Rizoma space in Palermo, the PH Museum of photography in Bologna, among others. Margarita works as a teacher of photography with an approach on decolonization at Bauhaus University and gives workshops in various foundations and institutions worldwide. Beltran is interested in the intersections between art, the politics of care, and apocalyptic fabulations. She is a member of diversify photo and Native Agency.

Follow Margarita on Instagram: @margarita.v.beltran

Vicente Cayuela: For a long time you were unaware of the political violence that compelled your father to leave Colombia. In Arder la casa, you explore the idea of your father’s exile as a turning point not only in your life but also your art. How has your understanding of your family’s history and yourself evolved through the process of creating this body of work?

Margarita V. Beltran: My father left Colombia in 2015, 15 years after he finished his term as mayor and many years after he stopped being politically involved. I was already an adult, and my life had changed significantly. … I vaguely knew he had some issues, but it didn’t seem serious until one day when I called to say hello, and he told me he wasn’t okay. That was the last time we spoke before he left, and it took us four months to communicate again. Having spent most of my life in a different city, my understanding of our separation had always been alluded to for any reason other than political violence. The past was blurry, filled with fairy tales my parents told me, but there was a deep, red wound in the middle that became increasingly visible after he left. What circumstances had I been unaware of that led us to this point?

Before my father’s exile, I was unaware of the influence that the armed conflict in Colombia had on our family. As a child I had heard stories from my aunts or cousins, stories that always seemed like fictions out of a magical realism tale and that I interpreted as alien to my reality. We never lived together as a family in the same geographic location, but that was attributed to my parents’ jobs, which were in different cities. At times my father, who called us daily, stopped calling us seasonally, my mother justifying his absence with work reasons.

It was only after his exile that through my research I managed to discover the hidden reasons for his absence, for our family fragmentation, for the sense of danger. This discovery was fundamental to expand my perspective on the violence in my country, to understand myself as a victim of the conflict and to speak from that place of enunciation. … My art underwent a complete transformation after that moment. I had never created art connected to the conflict in Colombia, but from that point on, I understood my voice as an artist to be deeply connected to that issue. This project has brought me closer to my identity as an artist.

VC: Can you tell us about the inspiration behind the title “Arder la casa” (Burning the house) and how it relates to the themes of family and visibility in your project?

MB: The title of the project came about two years after I had been working on it. I had used two or three tentative names that failed to invoke the intention of the project until the year 2021, while I was in an artistic residency in Bogota. Working on the research and recognition of the photographic archive, I came across a photograph from the family archive where a mountain was on fire. In the photo you could only see the smoke coming out of the trees, covering the landscape. I called my father to ask him about the history of this photograph and he told me that the fire had been set by his political enemies after he became mayor in 1997. It was his welcome to the political world of the town. I understood that the act of setting fire was fundamental to tell the story of my family, that to tell this story without putting anyone at risk, I had to leave some parts in anonymity, in the text or in the images, and that there was nothing better than fire, ashes or smoke to do it. I understood that to do this project I had to set the house on fire.

Hiding to reveal information, to cover, to protect, and not to put at risk — That was the strategy my parents had with my brother and me when we were children in the time of severe violence in the town where my father was mayor. They told us many fantasy stories to hide the violence we lived through, to keep us as far away from it as possible. In my extended family and in the town where I lived, people talked about the conflict using euphemisms. It was a survival strategy, “if you don’t call the devil by his name he will never appear”. The paramilitaries were called “the bad guys” so as not to create suspicion or make unnecessary enemies. In my project I make use of the same strategy of concealment to reveal the danger behind it. As it is a current, living history, maintaining anonymity is important to protect my family.

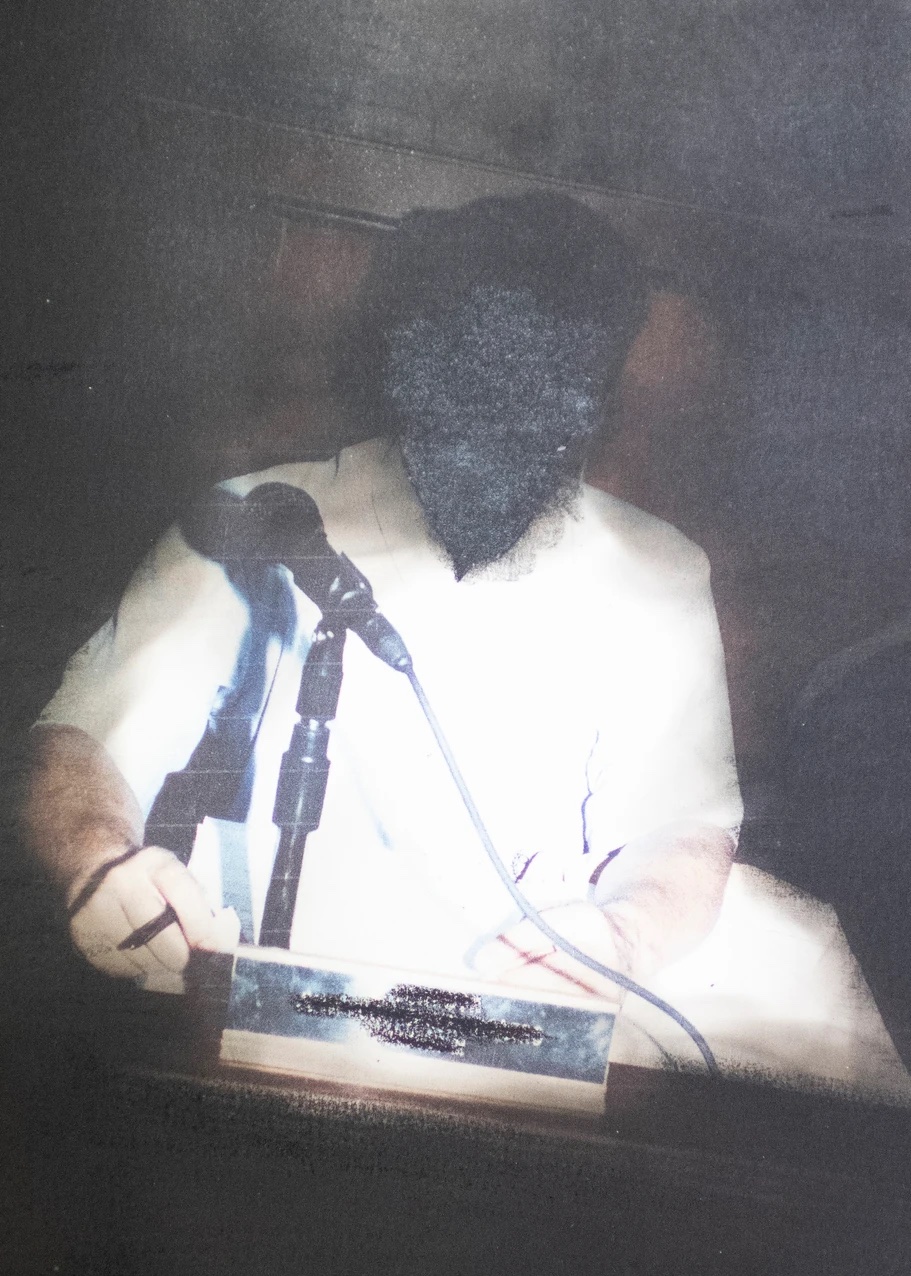

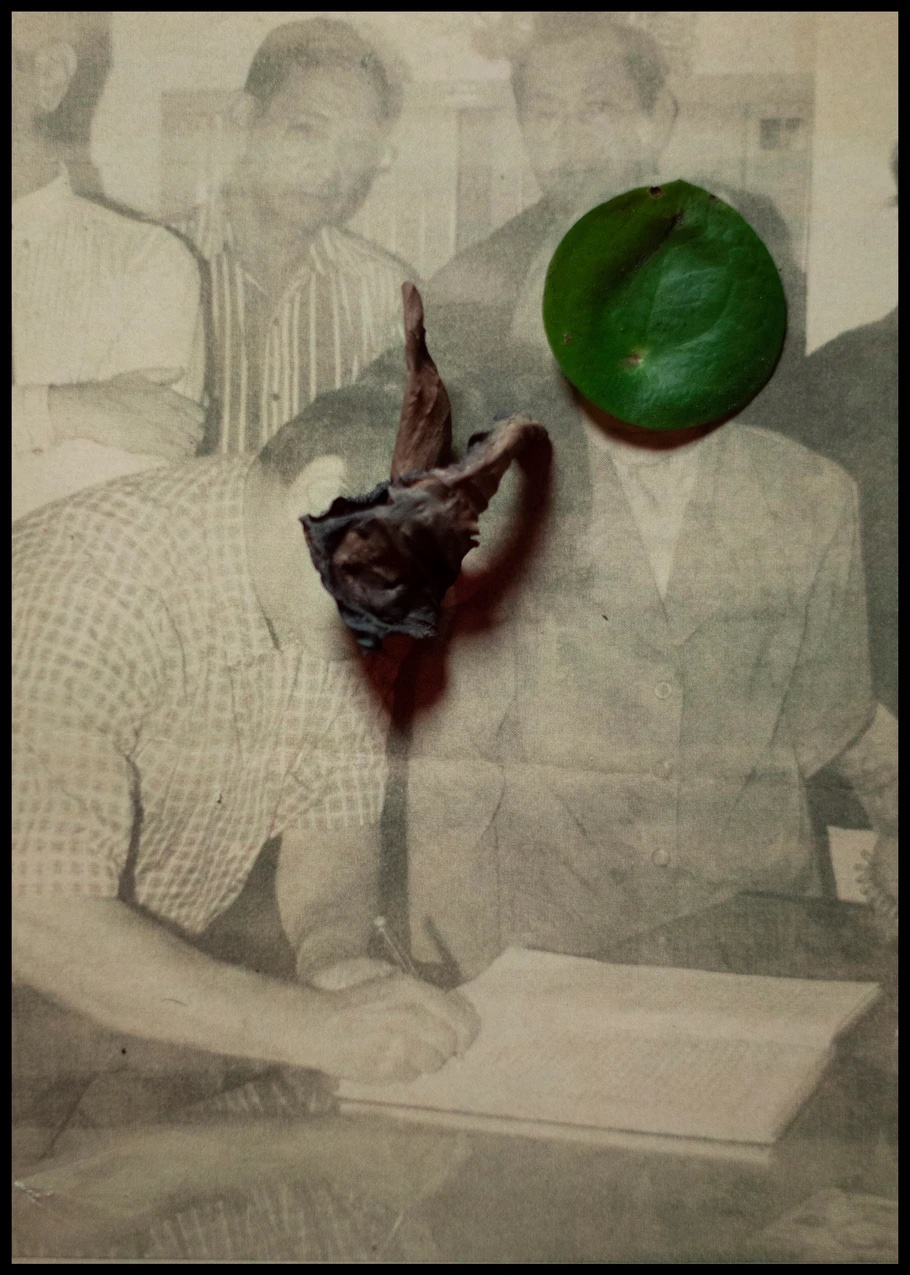

©Margarita Beltran, Arder la casa. “Chinacota, Norte de Santander, Colombia. Intervened archive image of one of the last political campaign gatherings of the “Movimiento Cívico” party in 1997. The faces of specific individuals are covered to protect their safety and ensure this story can be safely shared in public. Intervention made with fire and smoke in August 2021.”

©Margarita V. Beltran, Arder la casa. “A male family member sits on a horse seat belonging to his grandfather in the gardens of a farmhouse. The picture is staged and it represents faked idealizations of national symbols in the tales of heroes and revolutions in Colombia: a man in an invented horse, helped by invisible others.”

VC: What has the experience been like collaborating with your family on this project?

MB: It has been a very interesting and sometimes intense process to collaborate with my family in the development of the project. Except for a few archival photographs, all the people in my photos are my family: my mom, my brother, my aunts, my cousins, sometimes me. On the one hand, [collaborating] implies opening the conversation about our family trauma and listening to each other from our pain or fear, from our personal memories, and understanding each other’s positions. On the other hand, it is a way to rebuild our bonds of affection that have been worn out as a result of this conflict. Sometimes it has happened with my mother, one of the most photographed people in the project, that after taking a picture and showing it to her, she does not feel represented in the image. That’s when I realized that the reading I have about my family is ultimately personal, and that confronting the photo with its interpretation makes sense and is enriching, to talk about the imaginaries that each one of us constructs about that collective space.

VC: Have you had the opportunity to speak to other people with similar family histories?

MB: Yes, as part of my research I have connected with other victims, asylum seekers and refugees from Colombia and other parts of the world. Is a way to understand my own story and find commonality between our lived experiences, to find a community.

VC: Do you believe your project captures the experiences of other individuals who had to leave your country due to similar stories of violence, reflecting a broader narrative of Colombian exile?

MB: I think that the project captures the experience of the ones that are left behind. When we think about migration and forced displacement we often think about the people that have to leave, the ones that flee to other countries. But we often disregard what happens with the ones that cannot leave, the ones that stay. I wanted this project to be a voice for those who are highly affected by the separation but whose stories are hidden.

VC: Have your concepts of home and homeland changed as you saw your family and other people go through this process of displacement?

MVB: As I developed the project, it became clear that the concept of homeland, for me, implies multiplicity. I never had just one home, I moved around the country during my childhood and youth, and later during university and work, I traveled and lived in different continents. As my parents always lived in different cities, I grew up with the experience of distance, virtuality, and dislocation as part of my family reality. This project allowed me to be at peace with those circumstances and to recognize that not having just one homeland has allowed me to claim different places as part of my identity and consider them home.

VC: Your artist statement mentions the interplay of national myths and personal memories. Could you elaborate on how these two aspects come together in your work?

MB: Through this photographic project I rebel, I am critical and I play with the archetypes, with the ideological guidelines of my parents and my country. Our life is the result of their struggle but also of their blindness. Through my photos I want to satirize the myth, the heroism, the sanctity of certain figures that have been venerated in my family and in my country and that for lack of criticism have ceased to be revolutionary to become status quo. I combine objects that carry a strong symbolism with spaces that allude to memory, to memories of my childhood. It is a way to bring those fictions to reality and give them another meaning.

VC: I find this particular image of a sickle lit in fire to be one of those moments.

MB: Fire is use to threaten, instill fear and destroy evidence in Colombia. During The Palace of Justice siege in 1985 in Colombia, hundreds of criminal records and warrants were burned with rockets that the military used. My father’s coffee plantation was set on fire when he won the elections in 1997. In my project, I am playing with the different forms of fire: the living flame, the ashes, the smoke, the fire that is extinguished, etc. In this photograph, I was thinking about the symbols that have been part of that narrative construction of the proletariat, of the left in Colombia and in the world. At the same time I was thinking about how those symbols and objects have crossed my reality. That sickle has been hanging in my paternal house for decades as a decorative object in the house, as the representation of a family ideology. This photograph is an activation of that symbol in a space where it ceases to be a historical object and becomes a tool in use, allowing our history to be present.

VC: I love that you touch on ideas of historical activation because you are also working with archival documents, photographs, and ephemera. What is the most significant part of working with an archive and making it accessible to a larger audience?

MB: Working with archives has been wonderful to understand personal and collective visions and how they are staged in a photograph, in a text, in an illustration. The archive allows us to understand parts of the past and invokes atmospheres that could not be staged today. Navigating the universe of a story when there is an archive available is almost like having a paranormal encounter with our dead, I live it in a very ritualistic way and to be able to present that universe to the public is to invite them to join that encounter, that game with the past.

VC: You mentioned earlier that some of the stories you were told as a child seemed like fictions out of a magical realism tale. Has Colombia’s literature inspired your artistic approach to photography?

MB: I believe that magical realism in Colombia, beyond a literary style, is a reality of life that many of us experience. We live in a country where things happen that seem to be taken out of a fiction story, in Colombia there is a saying “reality surpasses fiction”. I could tell you many tales and stories, news that come out on television that would be perfect for a Marquez story. My influence is living in this town full of real characters that have gone to heaven and hell, have faced the gods, have danced with the devil, have given concerts to the dead and all of that has been true and has happened. For example, when I was a child, I was taught to greet the spirits, so that in case one day I ran into one, I would know how to respond.

VC: When I first saw your work, I was intrigued and captivated by your use of greens and reds. Do they play a special significance in your work?

MB: It was in the process of traveling, being, observing again and again this territory that the colors green and red appeared and consolidated as part of the aesthetics of the photographic essay. I traveled by car more than 16 times, crossing the central and western cordillera, twenty hours each way. I immersed myself in the thick green jungle that surrounds our farm, in the banana, bamboo or heliconia gardens that the animals tend. I walked in the mountains, swam in the river, and slept in every room of that house. And in every place I saw the green, alive, breathing. And then I understood that that green had to be in these photos and in this project because like it, history is also alive, speaking in past, present and future through the animals, through the landscape.

Something similar happens with the color red although in a more conceptual way, red in Colombia has a very specific connotation. It is in our flag portraying the violence that the country has suffered; it is related to the political left, to communism and socialism, to the guerrillas and the armed conflict that has been going on for more than 70 years. Red has been a color that has been vetoed, massacred, stigmatized, parodied and above all feared. It is a color that represents danger in this territory where history takes place and I am interested in using it as a metaphor for all these social and political relations in Colombia.

VC: I am also very interested in the scars and hands. Do they hold a particular significance?

MB: Yes, the wound is the foundational center of this story. It is a wound that runs through us as a family and as a country, and that I reveal in my mother’s body and mine, in her cesarean scar and in the idea of intergenerational trauma. It is a way of appealing to the intersectional perspective of how violence has done its deepest injury to the bodies of women and girls and has irreparably pierced us. Hands are important because they carry knowledge, history, community, through hands we connect, we protect ourselves, we learn from our ancestors.

VC: In addition to Arder la casa, you are also working on a short film, Toro Candela. It incorporates a highly distinct aesthetic that deliberately juxtaposes the tone of the photo essay. Additionally, it functions as a critical commentary on the portrayal of violence in Colombia, especially as depicted in television and media. What motivated the fusion of these two contrasting aesthetics?

MB: I was interested in making a parallel between the narrative function of the documentary style and the sensationalist fiction of the telenovela style that is very recurrent in stories about violence in Colombia in the entertainment industry. Our visual culture in Colombia, exported to the world, has been crossed by a series of tropes and stereotypes about the conflict, mafias, communism, drug trafficking, etc. that have simplified the reading of historical facts as complex as the armed conflict and that have been left without critical review, turned into entertainment. My interest in confronting these two styles is to generate a shock to the viewer, to bring his or her television-educated gaze closer to a space of intersection with his or her experience as a human being. As a living subject of a reality where these conflicts can be reflected.

VC: Can you tell us more about the production of this film? What has been the process for you?

MB: I decided that I wanted to make a short film based on an anecdote that my aunt told me in one of our interviews. It was the story of a fake funeral that was organized by the political opponents of my father, during the candidacy for the municipality. I was particularly interested in filmmaking as a medium as It would allow me to present the paraphernalia behind the story, to exaggerate gestures and to satirize the characters. It was also an exercise of understanding how the people that have hurt us the most, my father’s political enemies, the mafia clans in Colombia, operate, think, behave. I wrote the script based on the anecdote with the help of my aunt and contacted a production company in Colombia to shoot it. We decided to invite a group of natural actors that are former members of armed groups in Colombia, they were part of paramilitary groups, guerrilla groups, military and civilians victims of the conflict. It was a turning point in the making of the short film because it became a cathartic experience for all of us, understanding our role in this conflict, our collective delusion, our personal (wound, pain, trauma) and thinking, processing and feeling collectively. For me, it was a very vulnerable process of opening up this wound to show it to the crew and do something artistic with it. It was scary as I had never directed a film before; so being in charge of something so big felt overwhelming at times but also necessary and fundamental for my own personal process.

Vicente Cayuela is a Chilean multimedia artist working primarily in research-based, staged photographic projects. Inspired by oral history, the aesthetics of picture riddle books, and political propaganda, his complex still lifes and tableaux arrangements seek to familiarize young audiences with his country’s history of political violence. His 2022 debut series “JUVENILIA” earned him an Emerging Artist Award in Visual Arts from the Saint Botolph Club Foundation, a Lenscratch Student Prize, an Atlanta Celebrates Photography Equity Scholarship, and a photography jurying position at the 2023 Alliance for Young Artists & Writers’ Scholastic Art and Writing Awards in the Massachusetts region. His work has been exhibited most notably at the Griffin Museum of Photography, Abigail Ogilvy Gallery, PhotoPlace Gallery, and published nationally and internationally in print and digital publications. A cultural worker, he has interviewed renowned artists and curators and directed several multimedia projects across various museum platforms and art publications. He is currently a content editor at Lenscratch Photography Daily and Lead Content Creator at the Griffin Museum of Photography. He holds a BA in Studio Art from Brandeis University, where he received a Deborah Josepha Cohen Memorial Award in Fine Arts and a Susan Mae Green Award for Creativity in Photography.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Casey Lance Brown: KudzillaApril 25th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Larissa ArazMarch 28th, 2024

-

Rebecca Sexton Larson: The Reluctant CaregiverFebruary 26th, 2024

-

Mexican Week: Cannon BernáldezFebruary 6th, 2024

-

Erika Kapin: Mom and MeJanuary 19th, 2024