The Rebecca Senf Mixtape

From my position more generally as a photo historian and photo curator, I’m looking for photographers who are conveying something of themselves, that only they can say, through their artwork; and who have a good command of their craft, and are using their materials in a way that complements the message they are trying to convey. I consider it a bonus if they are able to clearly discuss what they are doing – that’s going to serve the photographer well, but isn’t at all necessary to my appreciation of their photographs (unless they communicate so poorly that I don’t understand the scope or depth of the project).

I met Rebecca Senf at a review event a couple of years ago and was impressed by her dedication to photography and to her commitment to her community. She is a thoughtful curator, one that shifts her focus from the historic to the contemporary, from the Arizona region to global communities, and from the grand scope of landscape and aerial photography to work that is more intimate and personal. It’s that breath of curiosity and focus that makes her unique. Not only does she straddle different photographic realms, but she straddles two amazing job positions, working for both the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona and the Phoenix Art Museum in Phoenix as the Norton Family Curator. She truly is a rich voice in the photographic community and it is with great pleasure that I present, The Rebecca Senf Mixtape.

Tell us about your growing up and what brought you to photography.

I grew up in Tucson, Arizona. My dad – like many men of his generation (and those that followed) – admired Ansel Adams’s photography and was, himself, an amateur photographer. My dad loved the desert landscape and was inspired by the way light and shadow revealed contours and textures and the range of colors produced by the setting sun. When I was a child, my dad would often sit and watch the shifting light on the Catalina Mountains in the early evening – he called it sun-on-the-mountain time. If I wanted to sit with him, which I was welcome to do, I had to sit quietly so the looking wouldn’t be disturbed. It made a big impression on me – the value of quiet observation. As a high school, and then undergraduate student, I found art history captivating. I attended the University of Arizona, which offers a three-semester survey of the history of photography. As I sat in the class (taught by Dr. Keith McElroy) and learned about Edward Weston and Charis Wilson and Alfred Stieglitz and Georgia O’Keeffe I decided that I wanted to be a photo historian. At that moment, I didn’t know what that meant, but I went on to complete a MA and Ph.D. in art history, both with a focus in history of photography. [I attended Boston University, which has a wonderful photo history program, and was one of a dozen or so programs at the time that had a photo historian – Dr. Kim Sichel – on the art history faculty. I was lucky to have a large group of cohorts, all pursuing doctorate degrees in the history of photography.]

What is your title and job description and tell us about a typical day?

My title is “Norton Family Curator” and I’m in a unique joint appointment between the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona and the Phoenix Art Museum. In my position, which was created in 2006, I am responsible for curating exhibitions from the holdings of the Center for Creative Photography and putting them on view at Phoenix Art Museum (about 100 miles north of Tucson). I live in Tucson and work most days of the week at the Center, where I can be close to the collection. I typically spend one day a week at Phoenix Art Museum, meeting with my museum colleagues, installing exhibitions, training docents, speaking to the public, hosting photography related programs or lectures, and meeting with photographers. Unfortunately, a typical day is spent in front of a computer screen, communicating with colleagues, artists, and donors by email, as I plan upcoming exhibitions. This includes all kinds of minutia and glorified secretarial work. But my favorite days are those where I’m either in the vault at the Center for Creative Photography, reviewing photographs for possible inclusion in an exhibition – or where I’m meeting with photographers during studio visits, portfolio reviews (either at one of my institutions or at a review event), or working together on a joint project. My job involves a lot of writing – exhibitions require proposals, descriptions, member magazine articles, brochure text, wall text, and object labels. I am also invited to write for book publications – often by the artist themselves.

There’s another aspect of daily work that is really important to me. Curatorial work is best learned through an apprenticeship process. I was fortunate, as a graduate student, to have five amazing years at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, working with a number of curators in the Prints, Drawings and Photographs Department. Looking closely at photographs with the guidance of a seasoned professional is the best way to learn how to look at prints and to articulate what you see. I also learned other aspects of the job – like learning how to talk with artists and donors, or how to organize an exhibition to best convey your ideas and vision – by repeated exposure to my curatorial mentors as they did their work and brought me in to their process. As a curator at the Center for Creative Photography, where we exist alongside the photo history and studio programs of the University of Arizona, I get to work with incredibly talented graduate students. The time I spend working with interns, sharing what I’ve learned, and drawing on their considerable knowledge and insight, has been one of the rewarding elements of daily curatorial work.

What are some of your proudest achievements?

Is it too greedy to list three? From an exhibitions standpoint, I have had a number of shows that I felt were successful, or beautiful, or resonated well with our audience and that’s always gratifying. In 2010, I got to curate a major exhibition for the Phoenix Art Museum called Ansel Adams: Discoveries. My goals for the exhibition were to include objects from the Center’s Ansel Adams Archive, to represent Ansel Adams as a person (not just the maker of photographs), and to demonstrate the depth and variety in his career that often gets overlooked in “greatest hits” books, calendars and exhibitions. The exhibition drew on my doctoral dissertation research, and gave my scholarly knowledge and understanding of Ansel Adams a beautiful, informative, and effective incarnation. It was a massive undertaking, and a complex collaboration with dozens of colleagues at both the Center and the Phoenix Art Museum. It was a struggle and required a steep learning curve, but the feedback we received was so overwhelmingly positive that I’m especially proud of that show.

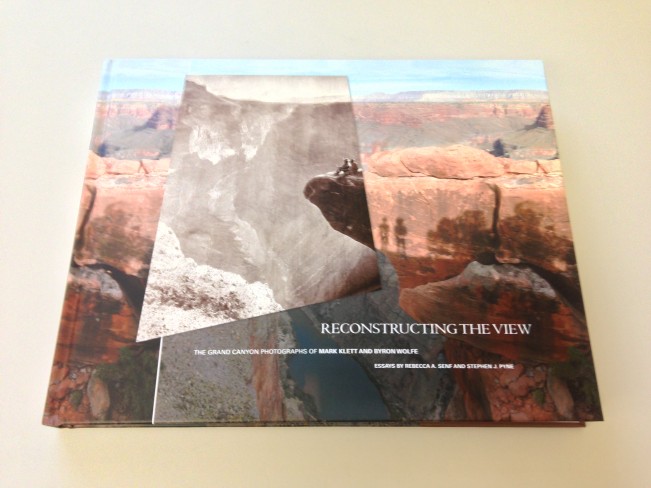

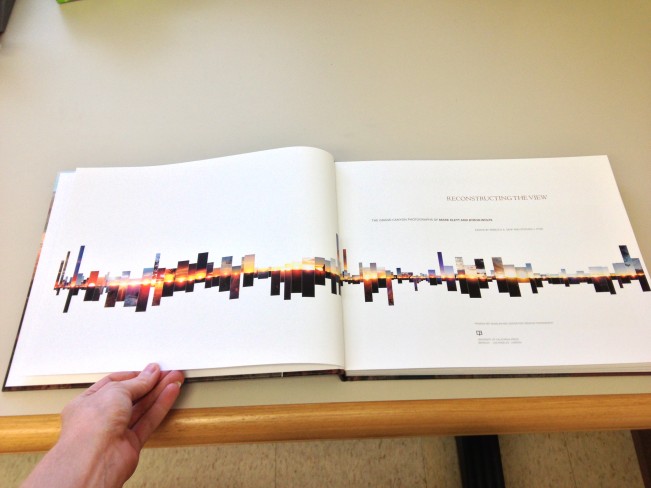

From a publications standpoint, I am incredibly proud and honored to have been able to work with Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe. In 2009, Phoenix Art Museum showed Mark and Byron’s collaborative work at the Grand Canyon with the title “Charting the Canyon.” At that point, they were just a few years into their fieldwork for the project. I had the chance to join them on one of their photographic trips to the Canyon’s South Rim and watch them in their working process. It was essential to be with them as they found locations, made photographs, and discussed ideas for potential photographs because their new work is about capturing the fun and discovery of the process in the final prints…and that’s what I wrote about in my essay for the book. In 2012, University of California Press published Reconstructing the View: The Grand Canyon Photographs of Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe. I enjoyed working with Mark and Byron, with the publisher at UC Press, with designer David Skolkin, and with the other writer, Stephen Pyne. Creating a book is hard work, but the lasting and tangible product is such a gratifying result!

Reconstructing the View: The Grand Canyon Photographs of Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe by Stephen Pyne and Rebecca Senf: Cover

Reconstructing the View: The Grand Canyon Photographs of Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe by Stephen Pyne and Rebecca Senf: title page.

Finally, I am very proud of the creation of a photography support organization at Phoenix Art Museum called INFOCUS. I am the first curator to hold the joint position between the Center for Creative Photography and the Phoenix Art Museum. The collaboration was inaugurated in November of 2006, and I began in April of 2007. In March of 2009, a group of volunteers set out to create a support organization to promote photography at Phoenix Art Museum by underwriting the publication of brochures; hosting a series of monthly programs including lectures, workshops, and collection and studio visits; and helping to fund exhibitions. Four years later the group has over 200 committed members, has contributed nearly $100,000 to the museum, has brought in nationally known speakers, does an annual members’ exhibition, hosts a fun and profitable silent auction fundraiser called PhotoBid, and allows me to do ambitious exhibitions and a hefty, illustrated brochure with each show. I work with the organization’s board of directors to help guide their programs, and I’m amazed by what they have been able to accomplish. And now we can expect that this group will continue to serve the museum for many decades to come!

What do you look for when attending a portfolio review?

I imagine that photographers come to portfolio reviews with certain hopes about what a museum curator might do: 1) museum curators will buy their work; 2) museum curators will give them a show; 3) museum curators will help them publish a book; and, 4) museum curators will provide useful feedback and advice.

I can’t speak for all museum curators, but I am rarely in a position to purchase work, give an exhibition, or help publish a book of an artist I meet at a portfolio review event. But I often liken the artist/curator relationship to gardening: an artist showing their work to a curator is like planting seeds. It could take years before anything comes to fruition, but if you don’t plant the seeds, nothing can happen.

I see my role as a portfolio reviewer thus: 1) to provide useful feedback and advice IF the photographer wants it; 2) provide answers to specific questions the photographer may have for me; 3) describe what I see in the photographer’s work, and articulate what I see as particular and/or unique strengths in the work; 4) offer suggestions of other people who should see the work; 5) mention artists, authors, websites, products, or ideas that I think may resonate with the artist based on what they’ve shown me.

So, to answer the question you asked, I’m looking on several different levels when I attend a portfolio review event. As a curator at the Center for Creative Photography, I’m most interested in photographers who may be doing something that relates to our collection. The collection includes the archives of twentieth century photographers such as Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, W. Eugene Smith, Lola Alvarez Bravo, Robert Heinecken, Garry Winogrand, Harry Callahan, Aaron Siskind, and Louise Dahl-Wolfe. So, I may ask myself, does this photographer’s work create a dialogue with material in the Center’s collection, and if that dialogue is rich and complex, then the photographer could be a valuable potential speaker, workshop leader, artist-in-residence candidate, or maybe even someone whose work we should acquire. From my position more generally as a photo historian and photo curator, I’m looking for photographers who are conveying something of themselves, that only they can say, through their artwork; and who have a good command of their craft, and are using their materials in a way that complements the message they are trying to convey. I consider it a bonus if they are able to clearly discuss what they are doing – that’s going to serve the photographer well, but isn’t at all necessary to my appreciation of their photographs (unless they communicate so poorly that I don’t understand the scope or depth of the project). I’m interested in seeing innovative or unique approaches to the medium – either conceptually, or related to process or materials – but obviously that’s not necessary for the artwork to be successful. As a curator of exhibitions at Phoenix Art Museum, I have some themes that I’m exploring for potential future projects, so I’m interested in panoramic photography, in platinum (and other alt process) photography, in projects dealing with issues of the Mexican-US border, and projects that attempt to capture the essence of past events. And then there are my personal interests: minimalism and abstraction; family, childhood and women’s issues; and portraiture. Of course, I’m always looking for all of these things, and when I find talented photographers whose work I love, their pictures are going to stay with me. I keep those people in my memory – like seeds waiting to sprout – until I have the opportunity to do something that I hope will be helpful. It may be a suggestion to another curator looking for photographers for a possible show, it may be an invitation to speak, it may be to nominate someone for an award or to write a letter of reference, it may be a connection to a private collector, or it may be curating them into an exhibition of mine.

Any advice for photographers coming to a review event?

If you have a special type of presentation – face mounted to plexi, or large prints, or special lighting, or an unusual way you arrange the prints on the wall – be sure you have a way to convey that to the reviewer. It’s not enough to describe it – you need to show it. So, bring some installation views, or a sample of the presentation. If you print large, inquire about whether you can display one or two big prints in the review room. If it’s not possible to bring a whole print at the full scale, consider bringing a portion of a print at full scale to convey the image quality at your preferred printing size. (I’ve seen people come up with all kinds of solutions to showing big prints, including cutting a print into parts, taping them back together, and folding it like a road map, which can easily be opened up for viewing and the returned to a small box.)

I prefer a “leave behind” to be an image-rich printed piece. I realize that blurb books (or the like) are expensive, but for me that’s ideal. It’s nice to see how the photographer presents their work in a book format, and it gives me a piece I can easily show to colleagues who I think may be interested. If that’s cost prohibitive, a large card or bi-fold that contains several images on front and back is also good. If you are showing more than one project, have a “leave behind” that shows each body of work (or multiple “leave behinds” – one for each project or group of pictures). Also, think carefully about the graphic design of the piece, and consider working with a designer if you feel uncomfortable about doing it yourself. As a visual person, I’m very sensitive to the quality of design, typography, color selection, image placement, etc. The better the design of your piece, the better overall impression you will make. [I don’t like to get a CD of images, but that’s my personal preference.]

If you are going to portfolio reviews, it is ESSENTIAL that you have a website. The most frequent way that I recommend photographers to curators and collectors is to send an email message with a short description of the photographer (which I write) along with a link to their website. Again, your website should be well designed and image rich, and if possible should include installation views, pictures of you working, links to press about you, images of your publications, and your contact information!

I know that the typical advice is to bring a small number of prints. Personally, I prefer to see more rather than less. If a photographer comes to me and says, “I have prints from these three projects, which do you want to see?” I always say, “Let’s see how much we can get through!” However, I have also had photographers bring one set of prints, and then show me additional work in books or on an iPad, which can also work fine.

Some of the most effective reviews I’ve had have been when a photographer brought a specific question – like, I’m ready to do a book, are there publishers you would recommend and who do you think might write for me? Or, I had a photographer once bring a big set of 4×5 proof prints of work they had done. She was trying to decide what direction to take her project and asked me to sort the proofs into ones I liked and ones I didn’t. That was a really practical way for me to convey where I imagined her work could go, based on ideas she had already explored. And, if you’re not looking for feedback about the work – for instance, you see the project as complete and you’re happy with it as is – go ahead and say that, and then articulate what you hope the reviewer can do for you – perhaps it’s recommend appropriate commercial galleries to show the work, or effective ways to get the project greater visibility.

Oh, and do not send a museum curator a photographic print as a thank you gift. It’s a conflict of interest for a curator to accept art work from artists. If we get a print, we have to return it – so it becomes a problem to deal with, rather than a welcome and thoughtful token. I suggest a hand-written thank you card – preferably a handmade one with your image(s) on it. I would also suggest sending a follow up thank you email, within a couple of weeks, if the reviewer gave you their card and/or email address. It can be helpful to have your email address easily accessible in one’s in-box.

If I meet you at a review, and then we run into one another in the future, please re-introduce yourself to me. I may not remember your face (especially out of context) but if you remind me what your work looks like, I promise, I’ll immediately know who you are!

What is something unexpected that we don’t know about you?

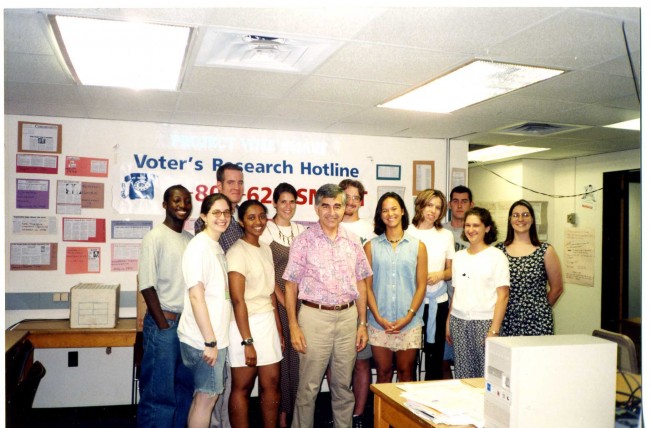

Between undergraduate and graduate school I worked for a political non-profit called Project Vote Smart that provided non-partisan voter information. Initially I worked in their press office, and then supervised a “voter information hotline,” which was a toll-free number people could call to get unbiased facts about their candidates for state and federal offices. It was an interesting way to be involved with politics – in a strictly non-partisan informational capacity, rather than as an advocate for a particular person or cause. I think it taught me diplomacy and how to keep my personal beliefs private. However, in a portfolio review I think I’m pretty transparent and people have said they can read what I’m thinking on my face!

Becky Senf (far right) in Project Vote Smart days, with student interns and Michael Dukakis (center). © All rights reserved Project Vote Smart.

And because this is a Mixtape, what is your favorite song, band, and do you dance?

I think I’d have to answer a question about favorite music the way I’d answer a question about a favorite photograph or photographer – it’s whatever I’m discovering right now. I listen to the radio and love having the music up loud in the car, singing along to the music with my kids. We play all sorts of radio games – guess who’s singing (and then check ourselves with the Shazam app on the iPhone) or try and name all the instruments we hear or talk about how best to remember which artist is which (I suggested trying to envision what they look like as you hear their voice). I love to dance and don’t do it nearly frequently enough.

And now Becky Senf takes over and creates her own playlist:

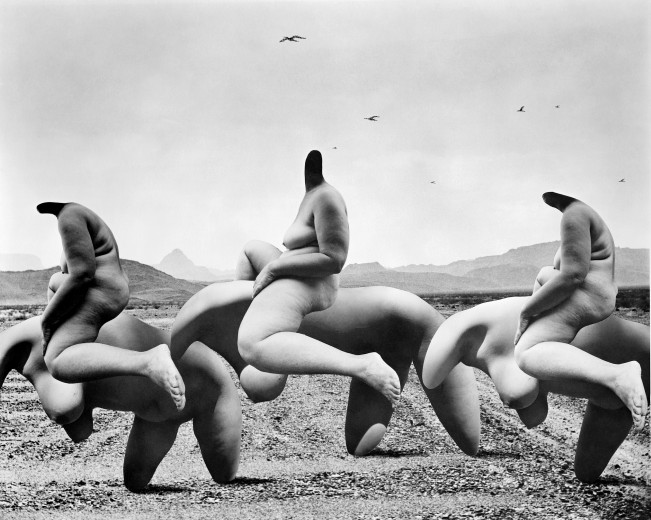

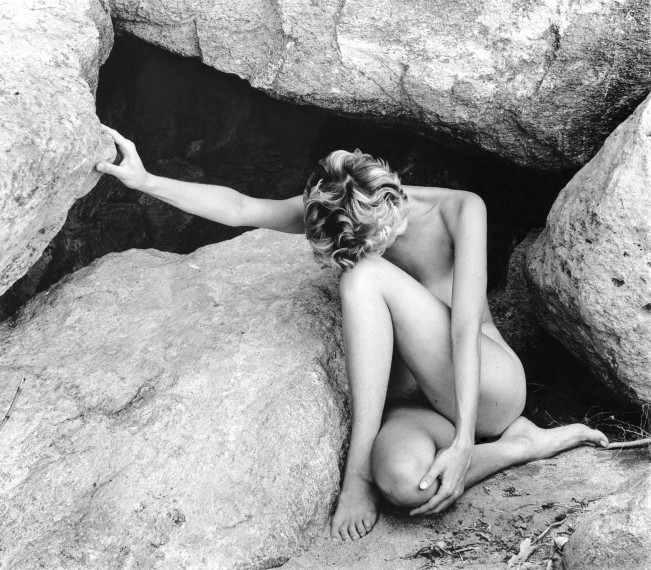

What a pleasure it is to get to take over an entry for LENSCRATCH! There are so many things I would love to discuss, but I have a local photographer that I would enjoy introducing to a larger audience. Allen Dutton, a 91-year-old Arizona native, has had many illustrious careers in photography, including working as a photographic educator at Phoenix College; curating the work of Minor White, Paul Caponigro, Harry Callahan, and Brett and Edward Weston for a Phoenix College gallery; creating a popular “Arizona Then and Now” publication; and pursuing his own fine art work, which is heavily influenced by surrealism. I had the honor of writing a biographical text for a revised edition of his book Real to Surreal, which will be available soon, through Tempe Camera (www.tempecamera.biz). That text is presented below.

The Many Lives of Allen A. Dutton

Sitting in the living room of Allen Dutton’s Phoenix condominium, I studied photographs spanning from the late-1950s to the 1990s. I had first gotten to know Dutton’s work through a portfolio of ten Hide and Seek nudes in the collection of the Center for Creative Photography, where I am curator. Completely intrigued by the Hide and Seek photographs – which seemed to combine the modernist intensity of Frederick Sommer’s horizonless desert landscapes with a playful silliness not usually associated with high modernism – I was eager to learn more about their creator. The opportunity to do so presented itself when I endeavored to write a history of important photographic institutions in Arizona, to complement a centennial exhibition called “Made in Arizona” which was presented at the Center for Creative Photography in the fall of 2012. Dutton, perhaps Arizona’s earliest photographic educator, had run a program at Phoenix College in the 1960s and 1970s which, in its seriousness to the principles of art, could rival many of today’s MFA programs. Indeed, Dutton, who was an early member of the Society for Photographic Education, taught most of the photography courses himself. In addition, Dutton created an exhibition program which brought the work of the medium’s masters to Phoenix, so his students (and the larger community) could experience what photography could do. He assembled a collection of photographic prints by Nathan Lyons, Brett and Edward Weston, Ansel Adams, Paul Caponigro and Minor White, and offered a new exhibition by a major photographer every two months. These exhibitions gained national recognition and soon photographers – including Harry Callahan – were approaching Dutton to be included.

I wanted to hear more about his experience as a teacher and curator, so I called the octogenarian photographer, and we enjoyed a lively and wide-ranging discussion. Although thirty years had passed since he had been active in the classroom, his investment in his students and his fervor for the experience had not waned. When I asked him about his goal for the students, Dutton focused on issues fundamental to art, rather than specific to photography, saying “I wanted the students to learn how to see, and to broaden their outlook. I still have students who can quote Sufi sayings because of my class. I wanted them to know that there is a much larger world of non-commercial photography. Photography can be revealing to the individual, and can help develop the whole person. I think the most important things to be gained from working with the camera are life enrichment and self-contemplation – getting to a place where there are no answers.”

Dutton, now ninety-one, has enjoyed several careers in his long professional life. In addition to being a photographic educator, his own photography has included periods of such distinctly different pursuits that sometimes it is hard to synchronize them as all belonging to the same man.

Allen Dutton was born in April of 1922 in Kingman, located in the northwest corner of Arizona. Despite the great distance between the cattle country of interwar Kingman and the bustling art centers of the eastern US and Europe, Dutton cites surrealism – and specifically, Salvador Dali – as a childhood influence in his interest in art. He persuaded his father to allow him to attend the Art Center School in Los Angeles, where he trained in painting and sculpting. After a semester in LA, Dutton returned to Arizona State College (later Arizona State University) in Tempe, Arizona, where he majored in science.

Dutton’s academic studies were interrupted by the United States entry into World War II ; he enlisted in the Army as an infantryman, and was stationed in Northern Africa. These many years later, Dutton’s experiences of the war remain vivid – as is to be expected. The stories he tells, however, are not typical expressions of heroism, youthful bravery, or even of realizing the miseries and horrible realities of war. Instead, when he speaks of North Africa he reminisces about the bonds he formed with his British counterparts when they learned that he could recite Kipling and Shakespeare. Even now, the stanzas and verses pour forth easily, as Dutton relaxes into familiar literature, and recites the words that helped him connect to the young soldiers he met decades ago.

Following the four years he spent in the Army, he returned to school in Tempe, majoring in history and minoring in art . For the next ten years Dutton taught art and civics in public schools around Phoenix. He then joined the art department at Phoenix College in 1960 and eventually became department head and photography program director, retiring in 1982. Early in his photographic career, and with no academic training in the medium, he sought instruction at a Denver, Colorado workshop with Minor White. Dutton credits White for having changed his outlook on photography. Over this period of teaching at Phoenix College and creating a stellar photography collection and exhibition program for the campus, Dutton also actively pursued his own artistic career as photographer, the fruits of which are presented in Real to Surreal.

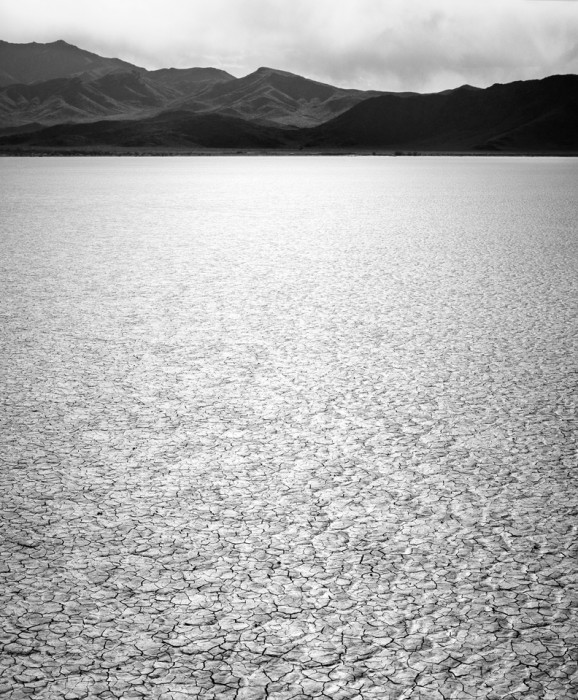

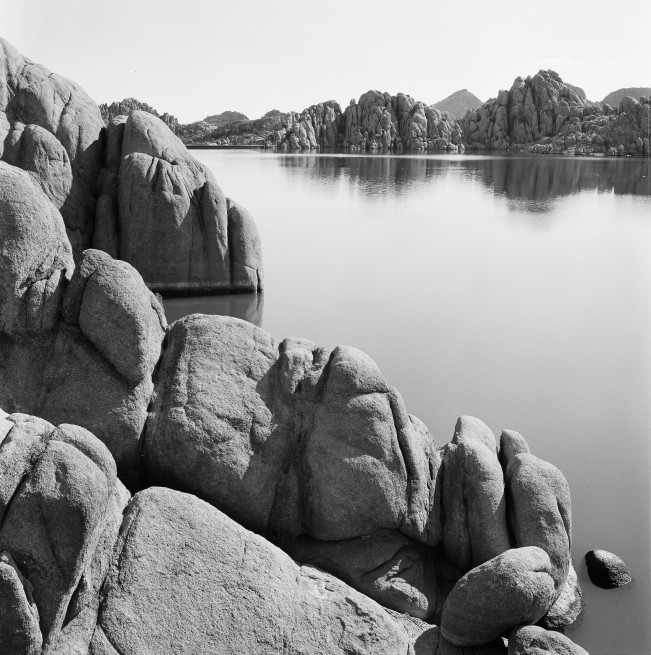

For Dutton, the Arizona landscape has provided an endless source of subject matter. His knowledge of trails, canyons, rock formations and desert vegetation meant that his large-format camera was endlessly engaged with new material. The desert, unlike more verdant landscapes, has a way of revealing itself, and for Dutton, many of his favorite places are charged with an intense vitality, one that becomes visceral. In these vibrant locations, Dutton’s photographs range from “straight” studies of cactus, skeletal trees, and undulating rocks, to scenes where he intervenes in the desert space, by inserting a nude figure (or perhaps more than one) or a staged explosion. Like a good surrealist, his creative work also includes many darkroom experiments, exploring how the negative might be transformed by solarizing the print in the development tray, by reprinting portions of a single negative to create symmetry, or by collaging elements from disparate shots into new compositions. All of these works, whether straight studies of the natural world or carefully crafted inventions, benefit from Dutton’s sharp wit and engagement with language. Titles, sequencing, and the use of section or portfolio titles help convey the humor, double entendre, and mystery Dutton feels is so crucial to his artistic output.

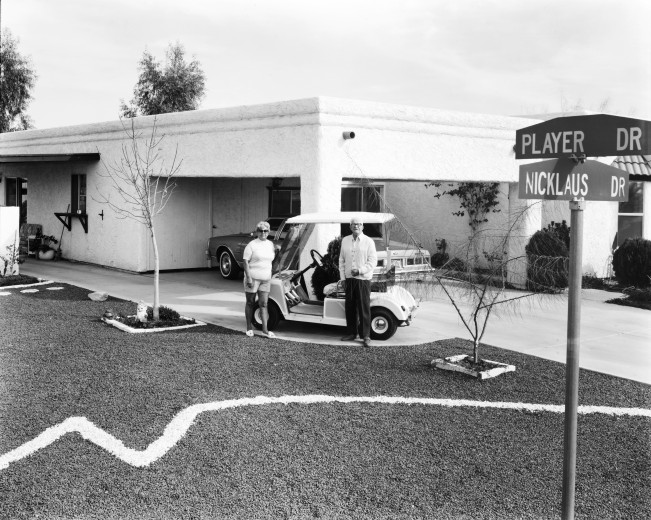

Another of Dutton’s photographic careers – one in which he was wildly successful – represents a more documentary impulse. Beginning in the 1970s, when he was still at Phoenix College, Dutton began making pictures of Arizona communities and their residents. Some, in newly developed and highly planned places like Sun City, captured the timely, and at times ironic, signs of Arizona in the midst of a dramatic transformation. The project grew, and Dutton began to rephotograph locations based on historic pictures. As the scope of this documentary project expanded, Dutton retired from Phoenix College to devote his energies to chronicling cities and towns throughout his home state with the detail and definition provided by the large-format view camera. The massive archive, including over 25,000 negatives, now resides at the Arizona Historical Society. The pairs of rephotographs, published by Westcliff Press as Arizona Then and Now, has sold over 30,000 copies – a phenomenal circulation of Dutton’s careful cataloguing of Arizona’s changing places.

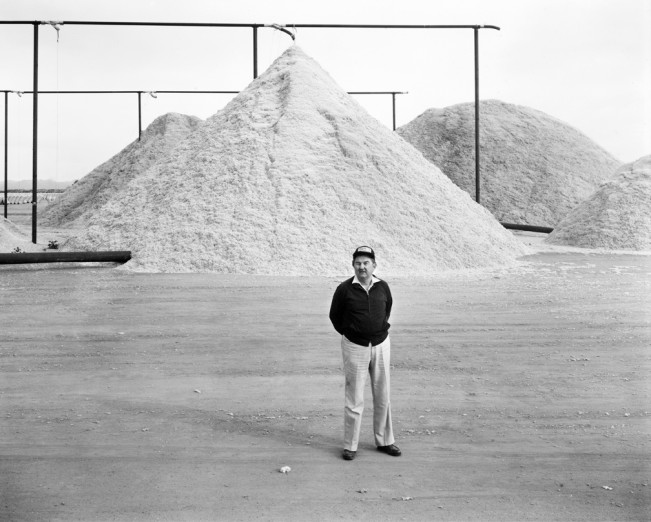

Allen A. Dutton, Peggy and Jack Williams at Nickolas and Palmer Drive, Sun Lakes, 1979. © Allen A. Dutton

Allen A. Dutton, Artillery Protecting Yuma Proving Grounds with Iowa Visitors, 1982. © Allen A. Dutton

Dutton has published eight books, including his recent Historic Rhinos of Arizona, which includes his paintings of a fictional Western estate (called the Rockin’ AD) where rhinoceros replace horses in the myriad functions of the ranch. He has had solo exhibitions world-wide, including in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Tokyo, Rome, Milan, Paris, New York, Albuquerque, Tucson, and Phoenix. An exhibition of his work at the Corcoran Gallery of Art entitled Strange but True: The Arizona Photographs of Allen Dutton included an exhibition catalogue by Paul Roth (2001). His work is in permanent collections nationally and internationally including Northlight Gallery, Tempe; Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art; Center for Creative Photography, Tucson; University of New Mexico Art Museum, Albuquerque; Santa Barbara Museum of Art; University of Louisville Photographic Archives; Princeton University Art Museum; Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven; Museum of Modern Art, New York; and the Kiyosato Museum of Photographic Arts, Japan.

Allen A. Dutton, Me and Old Drifter – Best Cutting Rhino on the Rockin’ A.D. Ranch, 1971. © Allen A. Dutton

Thank you Rebecca for all you do for photography and photographers…and introducing us to the amazing Allen A Dutton!

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The Christy Karpinski MixtapeDecember 2nd, 2023

-

The Rotem Rozental MixtapeJanuary 27th, 2023

-

The Brian Taylor MixtapeJune 14th, 2019

-

The David Rosenberg MixtapeMay 3rd, 2019

-

The Jonathan Blaustein MixtapeJuly 20th, 2018