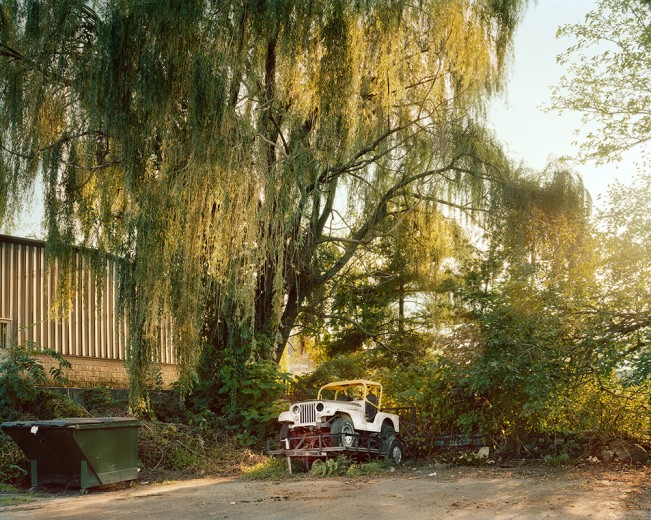

Thomas Gardiner: Untitled USA (2011-2012)

I don’t know what it is about large format work (in this case and 8×10). There is another level of emotion, of light quality, of detail that makes photographs more evocative. Perhaps it’s the slowed down nature of image making, where everything is considered over time and the ability to capture the work is limited. Thomas Gardiner brings all those qualities to his project, Untitled USA (2011-2012) but he also brings the ability to explore “human desire and the interior dramas within individual lives”. The combination of his visual and emotional interpretations take the work to a another level. His portrait work in Canada is also remarkable and was recently featured on Slate Magazine.

I don’t know what it is about large format work (in this case and 8×10). There is another level of emotion, of light quality, of detail that makes photographs more evocative. Perhaps it’s the slowed down nature of image making, where everything is considered over time and the ability to capture the work is limited. Thomas Gardiner brings all those qualities to his project, Untitled USA (2011-2012) but he also brings the ability to explore “human desire and the interior dramas within individual lives”. The combination of his visual and emotional interpretations take the work to a another level. His portrait work in Canada is also remarkable and was recently featured on Slate Magazine.

Thomas Gardiner graduated from Yale with an MFA in Photography in 2012. He earned his BFA from The Cooper Union, during which time he began working with a 4×5 camera to document the small communities he grew up in around Western Canada. During his studies at Yale he switched to 8×10, and began documenting working-class cities in the Northeast around New Haven. Thomas currently lives in Edmonton, Alberta.

Untitled USA (2011-2012)

I grew up in the isolated, hinterland regions of Western Canada. Economic life in these working class communities revolved primarily around resource extraction industries such as oil, potash, uranium, and farming. Far from large cities and the cultural centers of the world, I desperately wanted to leave the small towns of Saskatchewan. When I did eventually leave, I found photography. Returning home after several years living in Vancouver and then New York, I saw the people and places I left behind in a totally different light. Through the camera, Saskatchewan seemed like a place from another era, yet at the same time it felt more familiar than ever before. Now living in the US, I find myself searching the towns and cities of this new country for the places I knew in Canada.

When I photograph, the most important thing I look for is a kind of visual complexity in a space. I tend to find and return to urban communities where industry or manufacturing once thrived, ending up in back alleys, empty parking lots, behind strip malls, and in neighborhoods lost in the seams of the interstate freeway system—economically neglected places that reflect the nation’s disinvestment in its working people. Many of these environments— like the towns where I grew up— seem frozen or forgotten in time. Yet beyond any simple nostalgic attraction to these places, a contemporary theme is located somewhere within the challenging relationship of a visibly aging infrastructure in America versus the overwhelming crises of the modern world we live in today. Despite the apparent frozenness of these neglected spaces, time is still moving forward.

When I photograph, the most important thing I look for is a kind of visual complexity in a space. I tend to find and return to urban communities where industry or manufacturing once thrived, ending up in back alleys, empty parking lots, behind strip malls, and in neighborhoods lost in the seams of the interstate freeway system—economically neglected places that reflect the nation’s disinvestment in its working people. Many of these environments— like the towns where I grew up— seem frozen or forgotten in time. Yet beyond any simple nostalgic attraction to these places, a contemporary theme is located somewhere within the challenging relationship of a visibly aging infrastructure in America versus the overwhelming crises of the modern world we live in today. Despite the apparent frozenness of these neglected spaces, time is still moving forward.

Though there is certainly a documentary impulse throughout my work, even more important to me are the possibilities for the deliberate creation of a scene. The 8×10 view camera I use is traditionally regarded as a tool for exquisite detail, harnessed for its mimetic ability, for its higher descriptive fidelity. Yet my interest is in rendering those things generally less-easily seen: human desire and the interior dramas within individual lives. By using an 8×10 camera, I want the meditative attention to detail, but also I want the energy of the decisive moment, as is most commonly associated with smaller, faster, lighter cameras. My goal is always to attempt to overcome these limitations of the larger, slower 8×10 camera, and I feel it’s when I come close to this goal that the images are most satisfying to me. The result is a photograph with a unique kind of drama that is both fixed and transient.

Once a person has agreed to let me photograph him or her, I feel we have become co-agents in a kind of script. The individuals I meet have a concrete relationship to the environment where my camera is placed. My contribution to the script, however, comes from murky memories—psychological, visual, social, and more— of my own past. The people I photograph are in this way cast into those memory scenes, yet simultaneously their actions and decisions infuse the scene with new meaning. The photograph becomes a kind of dialogue, the end result often being a departure from what either photographer or subject imagined. For me, photography is a complete sensory experience. Despite these attempts to describe my photographic process, I firmly believe that attempts to spell out in words a photograph’s meaning are destined to reduce its power. While this isn’t to say that writing can’t aid in interpretation, there will always be something lost in translation. That is why I want viewers to consider these images without captions or theoretical viewpoints. And so the only title can be: Untitled, USA.

For me, photography is a complete sensory experience. Despite these attempts to describe my photographic process, I firmly believe that attempts to spell out in words a photograph’s meaning are destined to reduce its power. While this isn’t to say that writing can’t aid in interpretation, there will always be something lost in translation. That is why I want viewers to consider these images without captions or theoretical viewpoints. And so the only title can be: Untitled, USA.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Paccarik Orue: El MuquiDecember 9th, 2025

-

Lauri Gaffin: Moving Still: A Cinematic Life Frame-by-FrameDecember 4th, 2025

-

Dani Tranchesi: Ordinary MiraclesNovember 30th, 2025

-

Art of Documentary Photography: Elliot RossOctober 30th, 2025

-

The Art of Documentary Photography: Carol GuzyOctober 29th, 2025