Interview with McNair Evans: Confessions for a Son

This week, Lenscratch celebrates the SlowExposures Photography Festival.

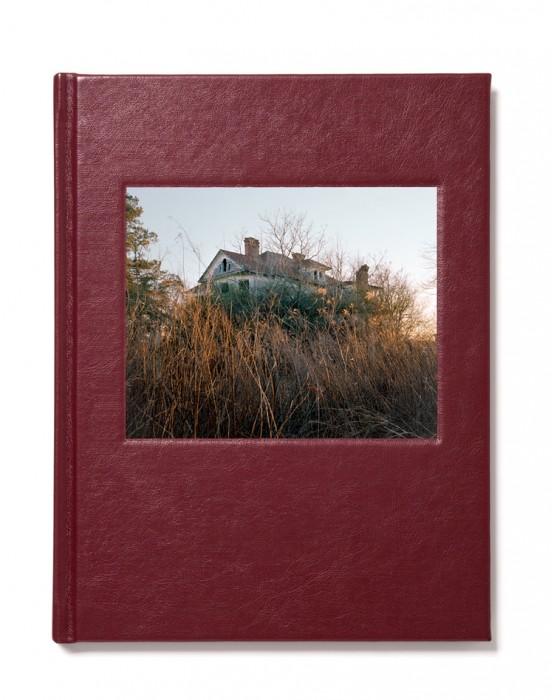

McNair Evans was given a solo show at the SlowExposures Festival after garnering first place in last year’s competition. His project, Confessions for a Son, was hung in a unique way, with various sizes of imagery with accompanying text. The exhibition was enhanced by his newly published book under the same title. His way of narrative is poetic and fluid, yet there is a unique tone that is distinguished in his sequencing and written word. I was unable to see his solo show at Slow Exposure, so instead I reached out to McNair. Below McNair shares, very thoughtfully I might add, his process and the long coming of this work.

McNair Evans was given a solo show at the SlowExposures Festival after garnering first place in last year’s competition. His project, Confessions for a Son, was hung in a unique way, with various sizes of imagery with accompanying text. The exhibition was enhanced by his newly published book under the same title. His way of narrative is poetic and fluid, yet there is a unique tone that is distinguished in his sequencing and written word. I was unable to see his solo show at Slow Exposure, so instead I reached out to McNair. Below McNair shares, very thoughtfully I might add, his process and the long coming of this work.

McNair grew up in a small farming town in North Carolina and found photography while studying cultural anthropology at Davidson College. He continued his education through one-on-one mentorships with highly acclaimed pioneers of new documentary practices, Mike Smith of Johnson City, TN and Magnum Photographer Alec Soth. His pictures draw parallels between the lives of individuals and universal shared experiences and are most recognized for a distinct and metaphoric use of light.

McNair’s photographs have appeared both in exhibition settings, numerous editorial publications such as Harper’s Magazine and the cover of William Faulkner’s novel Flags in the Dust. Confessions for a Son (November 2013 – January 2014) at San Francisco’s Rayko Photo Center, was the first major solo exhibition of his work. He has received many awards such as inclusion in “The Visual South: New Super Stars of Southern Art” # 36, by Jason Fulford, Oxford American, 2012 and CENTER’s Curator’s Choice Award juried by SF MOMA Assistant Curator Erin O’Toole.

Confessions for a Son

There was no man that my father admired more than his father, and no one his father admired more than the man who raised him. With tenderness of heart and warm humor my father met everyone as his equal.

Upon his death in November 2000, I was exposed to our family business’s insolvency. Dad faced a series of devastating fires, bad crops, perpetual over- extension and high-interest loans. Five generations of familial and financial stability fractured. While the economic effects were immediately obvious, the emotional implications lingered beneath the surface for nine years.

In 2010 I returned home to photograph the lasting psychological landscape of Dad’s legacy. Retracing my father’s life, I used photography to comprehend its events. Visiting the farms where we hunted, his college dorm rooms, and his oldest friends, I photographed his family members and businesses while researching his character and actions. I could not equate these.

Initially confused and angry, I grew to know him as a teenager, college student, co-worker, life-long friend, and father who lovingly withheld business realities. I witnessed shortcomings and successes and found empathy with a man who faced so much in his life. His sacrifices cost the ultimate price, and accepting that some questions may never be answered, I grew to love him again.

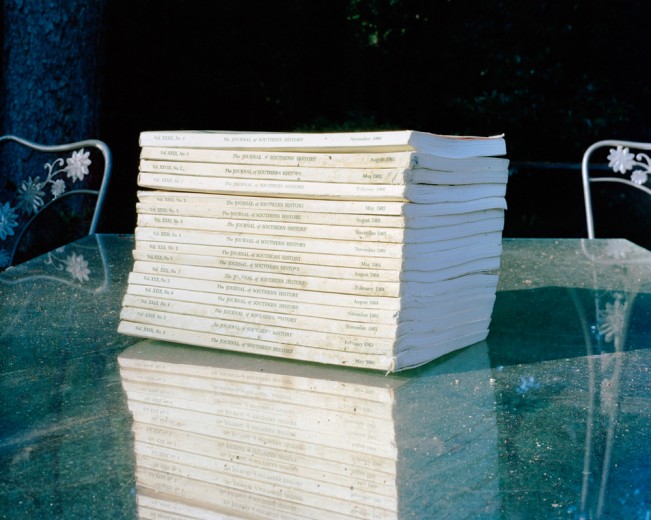

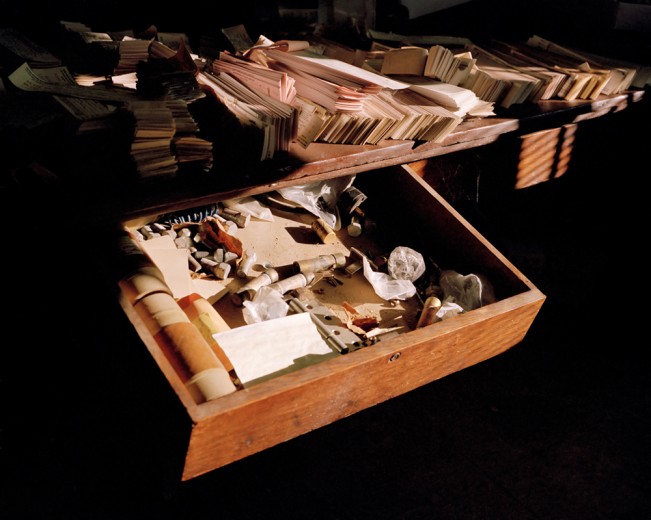

Confessions for a Son juxtaposes these photographs with those taken by my father roughly 40 years ago. Photographs from family archives and experimental practices join to explore this complex relationship between father and son. These works share my emotions after his death, my search to learn more abut him in recent years, and the journey of acceptance and forgiveness.

These pictures are my way of saying its OK. Everything that happened is done and it’s OK. They are my way of taking ownership of everything that I felt, and all the anger and all the shame, and saying, “Yes, I felt that, and it’s OK to feel that, and I still love you.”

Lets begin with the exhibition, how did this come to pass?

Lets begin with the exhibition, how did this come to pass?

I’ve worked with these pictures intermittently for roughly four years. The majority of shooting was done in 2010, with significant time editing in the spring of 2011. Over 2012 I worked very little on the project, beginning different bodies of work and slow baking the book dummies I had made, revisiting them every few months.

Elizabeth Avedon and I met at a portfolio review and she suggested I submit work for the Slow Exposures juried exhibition, an event celebrating photography concerning the rural south. In 2012 Julian Cox, Director of the San Francisco Fine Arts Museums and Brett Abbott, Chief Curator of Photography at Atlanta’s High Museum were the judges. Inspired by their work at current and previous positions, I wanted to meet both of them and Slow Exposures was the perfect opportunity. I submitted four pieces and won first place. The judges, panelist, and other photographers involved united for a national photography experience set in a tiny southern town. It was a wonderful mix of engaging dialogue with home cooked food. In 2013 I submitted photographs from a new project and won the first place Paul Conlan Prize, a solo exhibition scholarship newly endowed in commemoration of Paul Conlan. Paul was a dedicated photographer and event organizer who had unexpectedly passed away that year.

Over 2013 San Francisco’s Rayko Photo Center’s Artist in Residency program provided the resources and materials to print a major exhibition of this work. I used these eight months to reopen the project, adding new works, and further developing the photographic narrative. The Rayko exhibition hung from November 21st through January 16th, 2014, greatly informing the Slow Exposures installation where Aline and I met. Until the Rayko show, I had always thought of a show as either a single event or something rather stagnant, designed once and then replicated again and again in different spaces. This year, between February and September I came to recognize an instillation as an improvisational performance, like a band whose goal is to play their set of songs differently and better at each stop along the tour. Certain image pairings, sequencing, and object instillations of the Slow Exposure’s exhibition were completely unpredictable in advance.

What made you decided to go back nine years later? Why so long?

What made you decided to go back nine years later? Why so long?

For the first five years after my father died I worked as a fly fishing guide in the greater Yellowstone ecosystem. I was just beginning with photography, and I’d yet to develop a strong personal relationship with the medium.

In 2007 I moved to San Francisco in order focus solely on photography. By the end of 2009 I recognized how particular moods and feelings seemed to dominate my work regardless of subject matter. It was as if an undeniable voice made all of my pictures feel united in some inexplicable way. My efforts to make different types of photography all seemed to end up back at this overriding feeling, and I really didn’t know why.

I rarely visited home since Dad’s death. When I went home for an extended Christmas visit in 2008, I found the town heavily depressed economically. Like many small farming towns in the Southeast, downtown storefronts were empty and abandoned franchises circled the perimeter. Buildings from my childhood were vanishing and witnessing the town’s disappearance felt reflective of my own history.

I had been photographing commercial spaces left vacant in downtown San Francisco due to the 2008 economic crash. The pictures were intended to criticize franchise economics, but the humanity of these spaces overwhelmed my aspirations. Their emptiness resonated with previously unaddressed emotions caused by my father’s unexpected death, insolvency, and consequent family struggles. These vacated offices became visual metaphors for my own isolation and loss.

In October 2009 a call from my sister brought the project into focus. She had found our Dad when he died, and the trauma of that experience had grown troubling. At that point I recognized my work was not only reflecting the subconscious emotional realities of my life, but also was indicative of a broader emotional landscape affecting my entire family. Needing to justify the father I admired with the lasting impacts of his death and business insolvency, I returned home to photograph his life and legacy.

The book reads very poetic, and literally begins that way as well. What is the significance of this text? Where did it come from?

The book reads very poetic, and literally begins that way as well. What is the significance of this text? Where did it come from?

Photography and poetry have always had a lot common. Both mediums facilitate communication through mood and suggestion verses fact and definition.

The introductory texts you read are first-person, diarist accounts contextualizing the story geographically and emotionally. I had kept an intense journal during the shooting process, but it was primarily visual, comprised of image collages and ephemera, not much text. I was aware the pictures required supporting text, but everything written in my San Francisco studio felt detached. I had always heard of a private rail car used by my grandfather in the 50’s, but never knew what had happened to it. After a bit of research we located the car as a part of a historic railroad station installation in Rocky Mount, NC. I traveled to this train and spent one week there writing about the project. Most of the book’s text and ideas about how to use text were developed during this trip.

The book and exhibition both have a physical interaction, whether it is with the private notes that fall out of the book or the family photographs you present unframed on the wall. Is the intention to allow the viewer entrance through nostalgic empathy?

The book and exhibition both have a physical interaction, whether it is with the private notes that fall out of the book or the family photographs you present unframed on the wall. Is the intention to allow the viewer entrance through nostalgic empathy?

The physicality of the installation and book design are meant to engage a viewer on a less formal, more immediate level. Often times the formality of a book or installation distances a viewer from truly experiencing the work. These scenarios can over intellectualize the work causing us to learn about the art rather experience it. Consider the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin where a lack of formal signage and a grid of stelae is designed to create an emotional response empathetic to the ghetto experience rather than provide a history for intellectual consumption and understanding.

Both the installation and the book are constructed to create first person interactions that facilitate empathy with my experiences as well as those of my family. Finding a letter loose in the pages raises questions about it’s intentionality and feelings of voyeurism. While the work may feel tinged with nostalgia, most of the archive materials present a reckoning of the past versus a longing for it. The overall sense is that memories are or have faded thus are no longer reachable. Overwhelmingly these materials are about impermanence, naivety, and a fleeting serenity, and when juxtaposed with harsh materiality of the present the effect is an implied interplay between subconscious and conscious experience.

That said, there is one photograph that heavily embraces nostalgia and it’s the last picture of the book sequence, which shows my father holding my sister, flying a kite, and smoking a pipe.

Perhaps as mortal beings we always experience nostalgia when pondering impermanence, but a longing for the past is not a central theme to this work.

How do you think your father would feel about the work?

How do you think your father would feel about the work?

My Dad was an unbounded optimist, but also a very private person. At his core he was all love, and true altruism guided his every interaction. He shielded me from business realities unselfishly to protect me. At the same time he believed that he would be able to find a solution to this situation. These combined to create an Achilles heel.

With every installation people approach me about how they are inspired in their own lives. In one instance a fellow photographer in San Francisco said the show provided such an affirmation for the complexities of his own family relationships that he called his brother at work the next day to tell him that he loved him. The series inspired him to face his own family struggles and garner the strength to perhaps one day find peace.

This process of sharing our story so openly stirred many questions about my frustration, pain and also the deep gratitude and love for my father and the life he gave me. He would be deeply moved to see how this work reaches many people and gives them courage to work through their pain and find the peace that may result from that.

All content on this site cannot be reproduced without linking to Lenscratch and without the permission of the photographer.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026