Paradise Out-Front at the Southern Gallery

My idea of paradise might be pretty banal – simple beauty in an unadulterated landscape – but I can’t be any more honest than that. This photo was taken along a remote dirt road in Montana, a place I love. – Bryan Schutmaat

As part two of the Paradise Road exhibition featured yesterday, Eliot Dudik has curated a group of thirteen photographers tasked to respond with their own ideas of “paradise” for the exhibition Paradise Out-Front opening at the Southern Gallery on January 27th. This second part of the overall exhibition features unconventional and personal photographic works from Ben Alper, Ian van Coller, Mark Dorf, Matt Eich, Frances Jakubek, Thalassa Raasch, Jared Ragland, Justin James Reed, Anastasia Samoylova, Bryan Schutmaat , Aline Smithson, Katherine Squier, and Susan Worsham.

Paradise Lost and Found, an essay on both exhibitions by Lisa McCarty, Curator of the Archive of Documentary Arts, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University follows the imagery.

Bryan Schutmaat is a Texas-based photographer whose work has been widely exhibited and published in the United States and abroad. He has won numerous awards, including the Aperture Portfolio Prize and Center’s Gallerist Choice Awards, among many others. In 2016, Bryan earned an Aaron Siskind Individual Photographer’s Fellowship. He was also selected for PDN’s 30 new photographers to watch in 2014. His first monograph, Grays the Mountain Sends, was published by the Silas Finch Foundation in 2013 to international critical acclaim. Bryan’s photos can be found in the permanent collection at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; the Baltimore Museum of Art; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; The Hood Museum at Dartmouth, and numerous private collections.

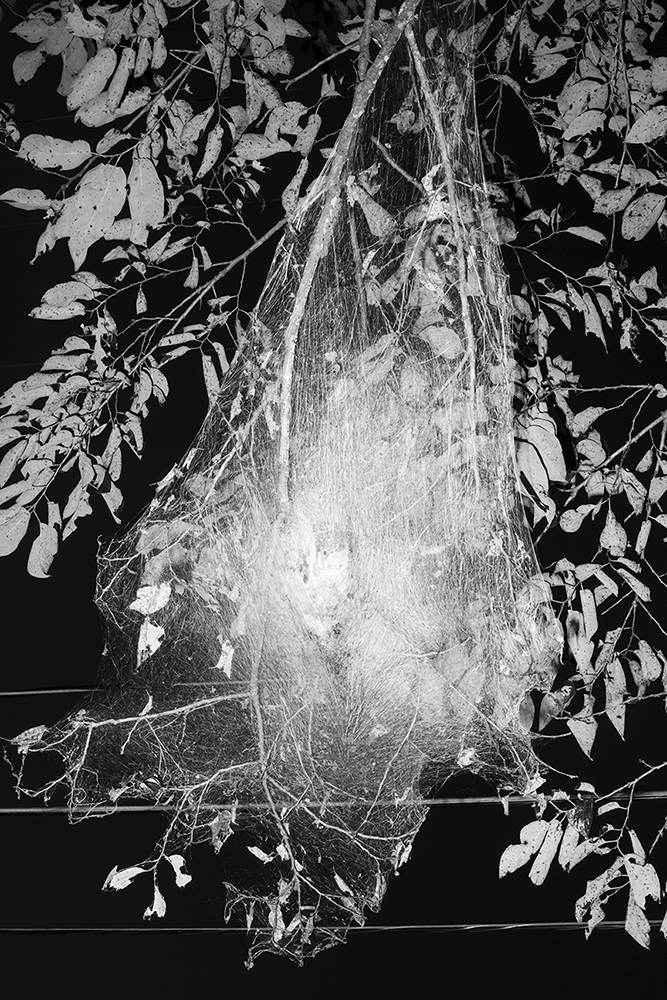

I see my images in this exhibition as visual manifestations of certain anxieties I have about the state of the world, but more immediately the state of our country. In this way, their relationship to the idea of paradise is paradoxical, in that they are markers of dislocation, unease and dystopia. Photography for me is so often a cathartic attempt to express things that are hard to say; these images are fragments of an apprehensive psyche. – Ben Alper

Ben Alper is an artist based in Durham, North Carolina. He received a BFA in photography from the Massachusetts College of Art & Design in Boston and an MFA in Studio Art from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Alper’s work has been shown widely, including in group exhibitions at the NADA Art Fair in Miami; Higher Pictures in New York; Le Dictateur Gallery in Milan, Italy; Schneider Gallery in Chicago; and S1 Gallery in Portland. Additionally, his work has been published in Time Magazine, The British Journal of Photography, Conveyor Magazine, The California Sunday Magazine, and Dear, Dave. Ben has also published three books – Adrift and A Series of Occurrences were both released under his imprint Flat Space Books. He is also the co-founder and co-facilitator of A New Nothing, an online project space dedicated to hosting visual conversations between artists.

There is so much I can struggle with in the world, but with my photos I can elevate ordinary moments into something I find exceptionally beautiful. In finding beauty in the mundane and capturing those moments in what I see as their full beauty, it gives me a way to create my own paradise to live in. – Katherine Squier

Katherine Squier was born with her sister on June 23, 1988 in Austin, Texas where she currently resides when she’s not traveling. She is a freelance photographer working mainly in fashion, but is always documenting her personal life on film. Light plays an important role in her work, as she captures those around her with sensitivity and intimacy. Her photos have been featured in shows around the world.

Paradise is the place where wonder and discovery meet. It is akin to finding a secret garden where you least expect it. This photograph holds all of the surface imagery associated with Paradise, it’s visual skin, referencing the landscape, tropical fruit, and fauna. As a photograph it is a view into someone else’s story, a curious world, opened up, by knocking on a stranger’s door. – Susan Worsham

Susan Worsham (born 1969) is an american photographer from Richmond, Virginia. Named one of Oxford American’s “New Superstars of Southern Art,” her work has been widely exhibited in the United States as well as internationally. In 2015, she received both a Lensculture Emerging Talent Award, and a Lensculture Portrait Award. She has been an artist-in-residence at Light Work in Syracuse, New York, where her work was published in Contact Sheet 168: Bittersweet/Bloodwork, as well as a recipient of The Franz and Virginia Bader Fund. Recent Exhibitions include, Light Work, Syracuse, New York; Camden Image Gallery, London; The Lishui 14th Photography Festival in China; Danville Museum, Virginia; Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans, LA ; and Candela Books+ Gallery, Richmond, Virginia. Her work is held in private and public collections including The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, The Ogden Museum of Southern Art, and The Do Good Fund Southern Photography Initiative. She was recently nominated for the 2016 Baum Award for an Emerging American Photographer, one of the largest national awards among the grants and fellowships available in photography. She is represented by Candela Books + Gallery in Richmond, Virginia.

Part of the appeal of our limited human perception of paradise is that at any moment, the illusion could all fall apart. This tenuous balance makes it that much more beautiful. Photographs of this paradise become urgent and necessary, because the dream could disappear in the span of a breath. – Matt Eich

Matt Eich (b. 1986) is a photographic essayist and portrait photographer born and based in Virginia. He holds a BS in Photojournalism from Ohio University and an MFA in Photography from Hartford Art School’s International Limited-Residency Program.

Matt’s work is widely exhibited in solo and group shows and his books and prints are in the permanent collection of The Museum of Fine Arts Houston, The Portland Art Museum, The New York Public Library, Chrysler Museum of Art and others. His long-form projects have received grant support from The Alexia Foundation, the Aaron Siskind Fellowship, NPPA Short Grant, National Geographic Magazine and twice received The Getty Images Grant for Editorial Photography.

Eich lives with his family in Charlottesville, Virginia while accepting commissions of all kinds and working on long-form photographic essays about the American Condition. His first book, Carry Me Ohio, was released by Sturm & Drang in October of 2016 and sold out in one month.

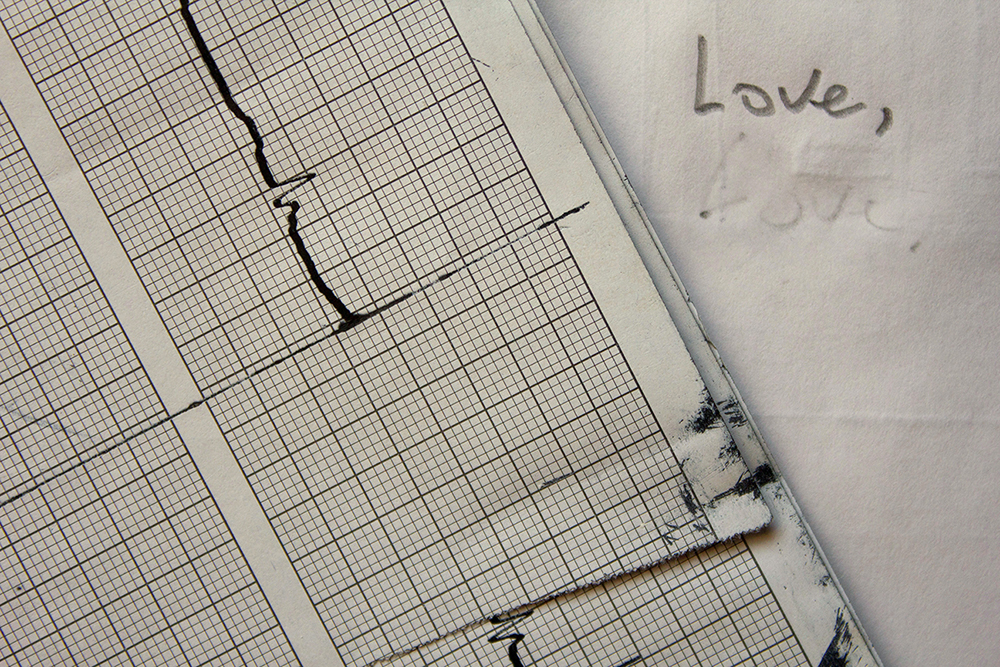

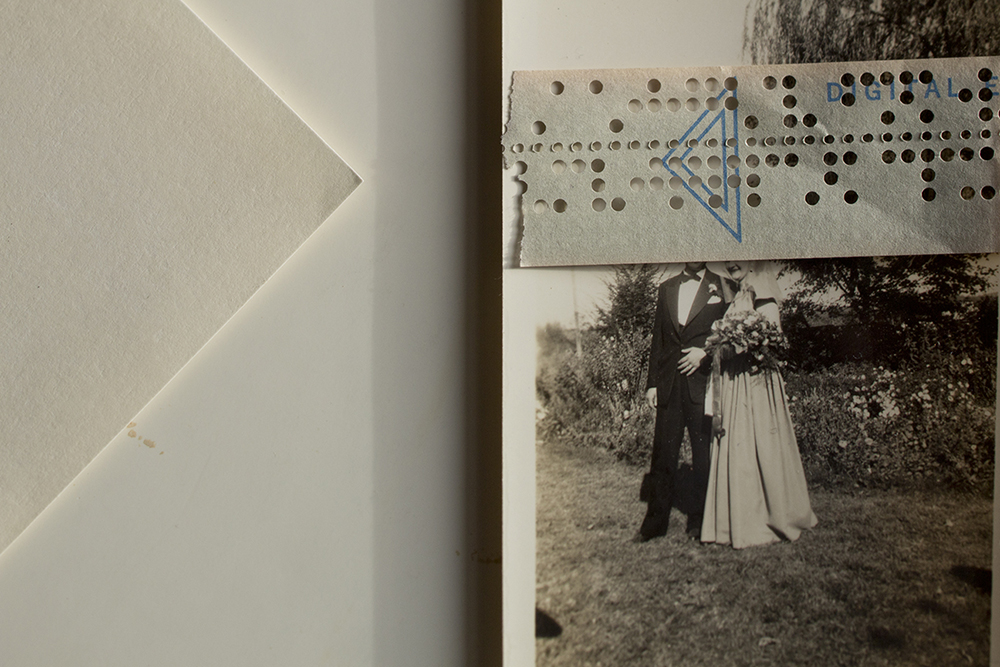

The road to Paradise is in the fine print. It’s in the gritty details and shaky penmanship, in the stories people don’t tell you until you can relate. Paradise is defined as “a very beautiful, pleasant, or peaceful place that seems to be perfect.” The “seems to be” denotes the variables that shift our perception and expectation of what this place should look like. The images from Carefully Omitted address the validity of objects I keep and what role, if any, they will play in my future version of Paradise. – Frances Jakubek

Born in Connecticut and grown in Boston, Frances Jakubek is a visual artist exploring photographic media to understand an ever-changing visual language. She graduated from The New England Institute of Art with a Bachelor’s Degree of Science focusing in photography and education.

Working as the Associate Director and Associate Curator of the Griffin Museum of Photography in Winchester, MA, she resides in Cambridge exploring new ideas and urging those to ask questions…and answer with more.

Digital technology has worked it’s way into every corner of our lives and by extension has forever changed the way we function as human beings in western culture. While these technologies aid us in our navigation of our day to day, there too comes malicious uses of these technologies to gather information, of which this function is often left unnoticed if a critical eye is not kept aware. Paradise is a place where all elements work seamlessly in harmony to create the best relationship amongst all kinds of people and the surrounding environment. This powerful consumer based technology is here to stay. we need to work towards a future that creates a harmony with these technological elements; where technology augments our existence for the better rather than distracting us from our day to day relationships and the underlying nature and function of the devices that we have in our pockets. – Mark Dorf

Employing a mix of photography and digital media, Mark Dorf’s work explores the post-analogue experience – society’s interactions with the digital world and its relationship to our natural origins. Dorf scrutinizes and examines the influence of the information age through the combination of photography and digital media, looking at, in his most recent works how we encounter, translate, and understand our surroundings through the filter of science and technology. Mark seeks to understand our curious habitation of the 21st century world through the juxtaposition of nature and the digital domain.

Dorf has exhibited internationally including at Galerie Philine Cremer, Dusseldorf, DE, 2016; Division Gallery, Toronto, 2015; Postmasters Gallery, New York, 2015; Outlet Gallery, Brooklyn, 2015; The Lima Museum of Contemporary Art, Lima, 2014; Mobile World Centre, Barcelona, 2014; Harbor Gallery, New York, 2014; SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah, 2013; and Phoenix Gallery, New York, 2012. Dorf’s work is included in the Fidelity Investments Collection, the Deutsche Bank Collection, and the permanent collection of the Savannah College of Art and Design.

At a time when I had misplaced, or lost, a personal sense of paradise, I went out to the edges of my yard and began making a series of sculptures—with dirt, with velvet, with light. They were photographs that I had dreamt up as mysterious monuments to my overwhelming grief after losing three family members in a short period of time. – Thalassa Raasch

Thalassa Raasch is a French-American artist and photographer whose practice explores perceptual boundaries, translation and loss. Her research has included blind photography, traditional gravedigging and closed-eye hallucinations. Her work has been exhibited nationally and published internationally. Recent awards include the SPE Student Award for Innovations in Imaging (2016) and two RISD Graduate Studies Grants (2015, 2016). Raasch holds a BA in Visual and Environmental Studies from Harvard University (2010) and a Masters in Photography from RISD (2016).

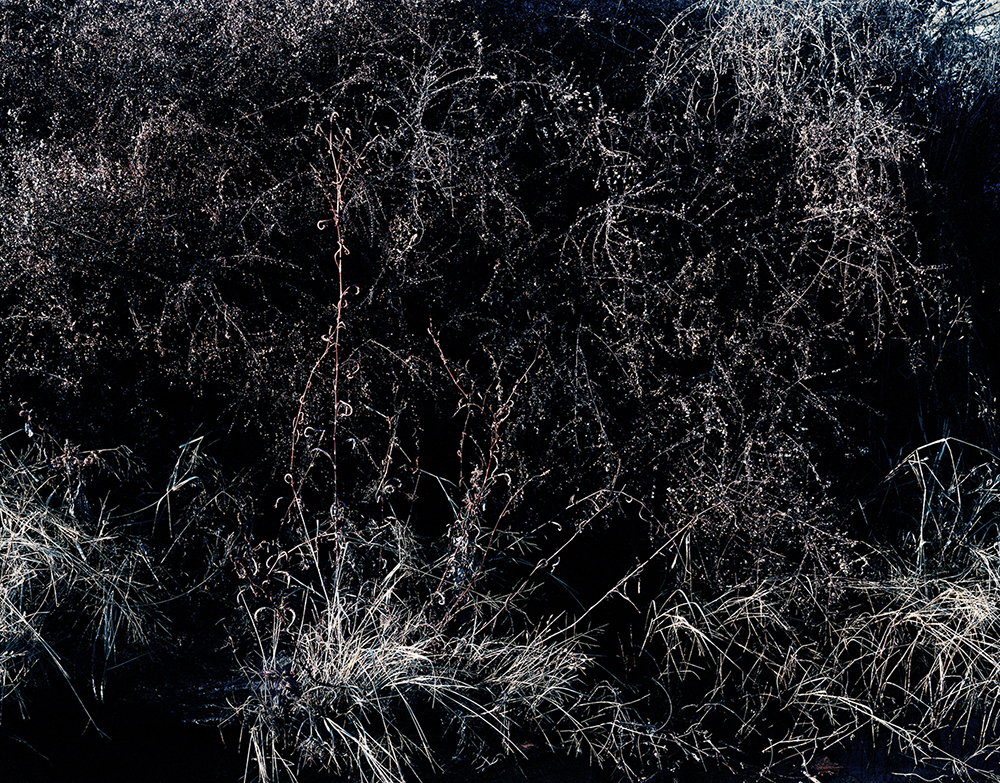

These photographs are a physical manifestation of my psychic connection to a landscape and pursuit to unify the mysterious aspects of observation. This search for meaning, and ultimately a spiritual connection to the natural world, is representative of my desire to connect with where we came from and ultimately where we are going back to. – Justin James Reed

Based in Richmond, Virginia, (USA) Justin James Reed’s work and artists’ books have been exhibited widely, including at Higher Pictures (New York), Carroll and Sons (Boston), Atelier Néerlandais (Paris), Unseen Photo Fair (Amsterdam), and Depot II Gallery (Sydney). His work is in numerous collections, notably the Library of Congress, Yale University Art Gallery, The New York Public Library, MoMA Library, Stanford University Libraries, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, and Dartmouth College. Justin is co-publisher at Brooklyn based Horses Think Press and an Assistant Professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, School of the Arts.

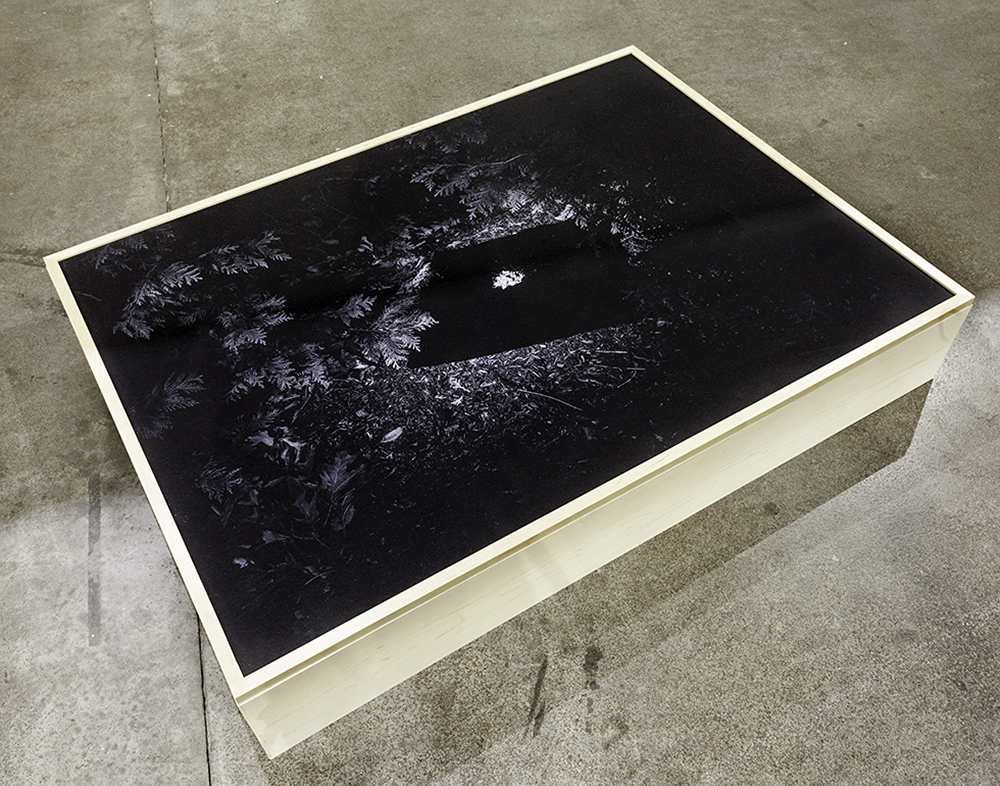

The concept of Paradise is inextricably woven with the concept of place, and therefore landscape. In my photograph I explore how Paradise is represented in contemporary visual culture based on the images that come up in Google image search under the keyword “paradise”. The resulting tropical utopias are printed out and reassembled into a table-top tableau, which is then re-photographed to produce the final image. – Anastasia Samoylova

Anastasia Samoylova was born and raised in Moscow, received an MA from Russian State University for the Humanities, and an MFA from Bradley University. She served as an assistant professor of photography at Illinois Central College and Bard College at Simon’s Rock. She is currently based in Miami, where she is an artist resident at the Fountahead studios.

By utilizing tools and strategies related to digital media and commercial photography, her work interrogates notions of environmentalism, consumerism and the picturesque. Samoylova’s work participates in the landscape photography tradition while scrutinizing the consumable products it generates. Samoylova has exhibited internationally, including Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, Griffin Museum of Photography in Boston, and Pingyao International Photography Festival in China. Her work is included in the collection at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago and ArtSlant Prize collection in Paris. In 2015, she was granted an artist residency at Latitude Chicago. Her work has been featured in the New Yorker and Foam magazine.

Her first monograph, Landscape Sublime, was published by the In the In-Between Editions in June 2016.

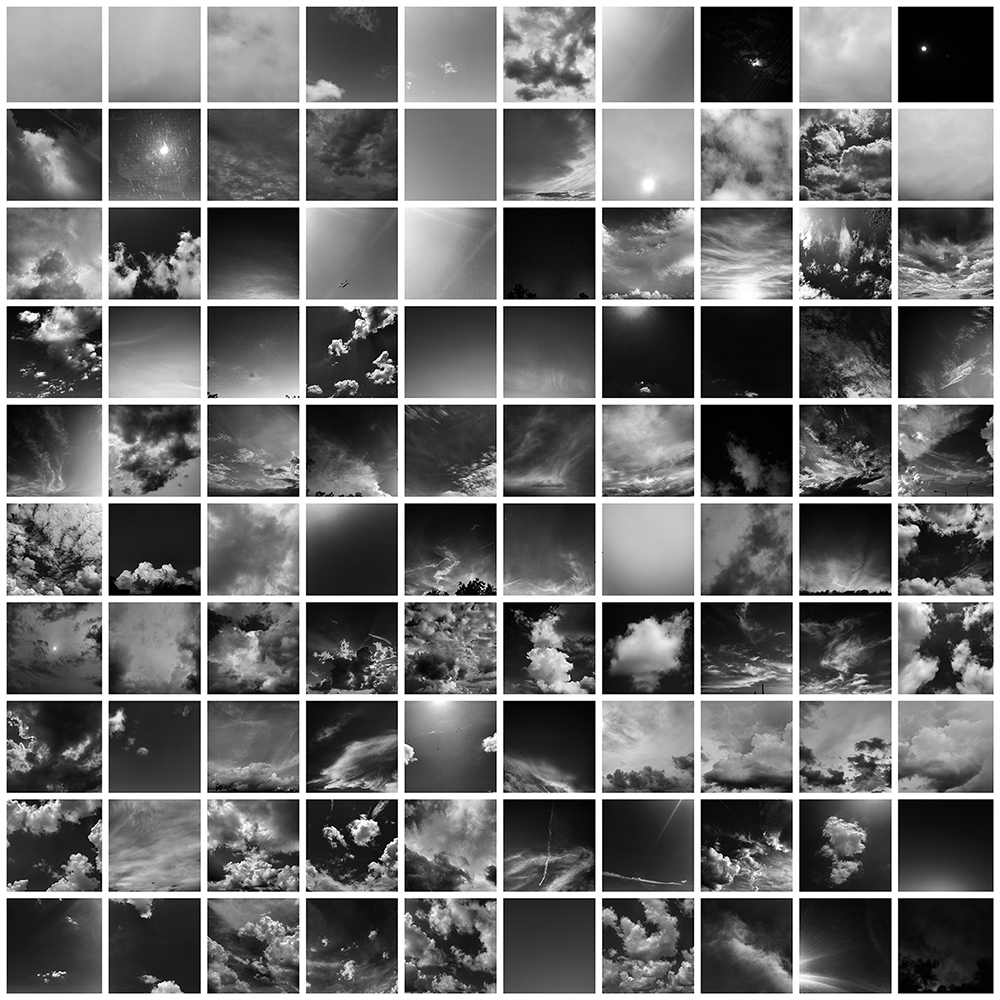

When thinking about paradise, I am immediately drawn to the traditionally religious, skyward notions of the idea. In 2015, as an homage to Alfred Stieglitz, the father of modern photography and creator of the renowned series of cloud pictures he first titled, “Songs of the Sky,” and later renamed “Equivalents,” I created a project-specific Instagram account in which I photographed and posted a picture of the sky nearly every day for an entire year.

Just as Steiglitz’s cloud pictures were imbued with a symbolist aesthetic, and over time, became increasingly abstract equivalents of his own experiences, thoughts, and emotions, so too did my pictures assume symbolic weight and personal meaning. Shortly after beginning the project on the Spring 2015 Equinox, my mother was diagnosed with terminal cancer, and the act of making these images quickly took on a kind of liturgical significance. Each picture became a brief meditation – a prayer – for mom as I marked the passage of another day and considered the nuances of light, space, form and texture overhead. The series includes images made on the day she was diagnosed and the days we spent together at home and in the hospital. They mark the day she died, the day she was buried, and the difficult days that followed. – Jared Ragland

Jared Ragland is a fine art and documentary photographer and former White House photo editor. He currently teaches and coordinates exhibitions and community programs in the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and is at work on a long-term documentary on methamphetamine users living on Sand Mountain in northeast Alabama. He is the photo editor of National Geographic Books’ The President’s Photographer: Fifty Years Inside the Oval Office, has worked on assignment for NGOs in the Balkans, the former Soviet Bloc, East Africa and Haiti, and in 2015 was named one of TIME Magazine’s “Instagram Photographers to Follow in All 50 States.” His photographs have been exhibited internationally and featured by The Oxford American and The New York Times.

Prior to his current work in academia, Jared spent six years as a photo editor for the Bush (43) and Obama Administrations. During his tenure at the White House, Jared edited and created photo books for the President, Vice President, Cabinet and First Family, curated and installed photographic exhibitions in the West Wing of the White House and at the Leica Gallery New York, Leica Gallery Berlin, and New York Public Library, and was part of the editing team responsible for the release of the now iconic photographs of President Obama in the Situation Room during the raid on Osama bin Laden.

Jared is an alumnus of LaGrange College and a 2003 graduate of Tulane University with an MFA in Photography. He resides in his hometown of Birmingham, Alabama.

At the end of the 19th century, Butte mines were the largest producers of copper in the world, with the dominant share of the copper wire used to electrify the United States and the rest of the world coming from this one mountainside. Men came from all over the world seeking work and a better life. One man, W.A. Clark, became one of the richest men in the world, while the majority of residents struggled to live modest lives. After a long, slow decline in production and copper markets, the eventual abandonment of the copper mines left behind the largest superfund site in the country, including hundreds of miles of underground tunnels that today are filled with water contaminated with every heavy metal imaginable, and will continue so in-perpetuity. Today, the town remains a center of blue-collar and union values within the conservative state of Montana; and Butte residents continue to celebrate its tumultuous “hard scrabble” history with pride, even as it reinvents itself and a new generation comes of age. – Ian Van Coller

Ian van Coller is a member of The Piece of Cake Collective. www.pocproject.com. He was born in 1970, in Johannesburg, South Africa, and grew up in the country during a time of great political turmoil. These formative years became integral to the subject matter van Coller has pursued throughout his artistic career. His work has addressed complex cultural issues of both the apartheid and post-apartheid eras, especially with regards to cultural identity in the face of globalization, and the economic realities of every day life. Van Coller received a National Diploma in Photography from Technikon Natal in Durban, and in 1992 he moved to the United States to pursue his studies where he received a BFA in photography from Arizona State University, and an MFA in photography from The University of New Mexico. He currently lives in Bozeman, Montana with his wife, children, and two dogs and is an Associate Professor of Photography at Montana State University. His work has been widely exhibited in the United States and South Africa, including 20 solo exhibitions and over 70 group exhibitions, and is included in many significant museum collections including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Library of Congress, The Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Fogg Museum, The Getty Collection and The South African National Gallery (IZIKO). Van Coller is represented by JDC Fine Art in San Diego, Passages Bookshop in Portland Oregon and Schneider Gallery in Chicago, Illinois.

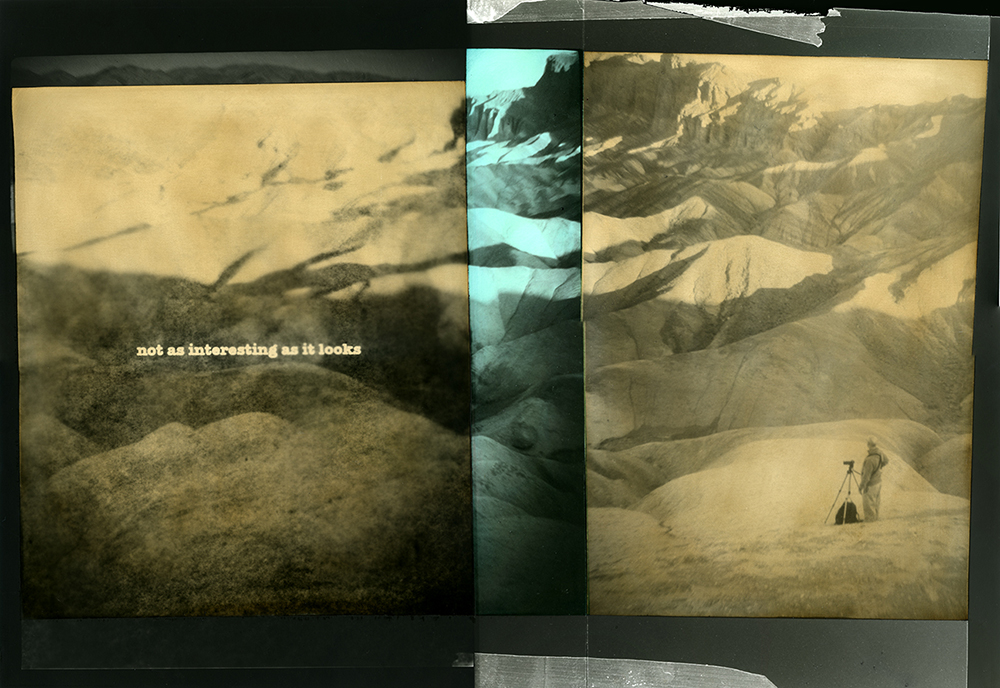

This series takes a look at the idea of photographic paradise and turns it upside down, poking fun at iconic landscapes and the visual draw of the land. The rapture of Western topographies are often considered “promised lands” for traditional photographic sensibilities, where Not as Interesting and Nothing to See question the reverence for wide open spaces and explore the possibility that these vistas are not the Arcadia of subject matter. – Aline Smithson

Aline Smithson is a photographic artist, educator, and the founder and Editor-in-Chief of Lenscratch. She curates and jurors exhibitions for a number of galleries, organizations, and on-line magazines. In addition, she is a reviewer and workshop instructor at many photo festivals across the United States. In 2014, Aline received the Excellence in Teaching Award by CENTER and her work was selected for the Critical Mass Top 50 Portfolios, Review Santa Fe and the PDN Photo Annual. In 2012, Aline was recognized with the Rising Star Award through the Griffin Museum of Photography for her contributions to the photographic community

After a career as a New York Fashion Editor, Aline is now represented by galleries in the U.S. and Europe and published throughout the world. She has exhibited widely including numerous solo and group exhibitions and her work is held in a number of public collections. Her photographs have been featured in publications including PDN, The New Yorker, Communication Arts, Eyemazing, Soura, Visura, Diffusion, Rangefinder, Lenswork, Shots and Silvershotz magazines. In 2015, she released a retrospective monograph, Self and Others, published by the Magenta Foundation. Aline lives and works in Los Angeles.

PARADISE LOST AND FOUND

That crazy feeling in America when* you realize that paradise is precarious; that it is not a fixed place or even a stable, shared notion.

The idea of paradise has persisted for as long as stories have been told, yet there has never been consensus on what it is, where it is, and if it can be reached. There may in fact only be two commonly shared beliefs concerning paradise, the first being that there are infinite definitions of it. However, if paradise is in the eye of the beholder, then how do we begin to contemplate what it can be to one and all in the present moment? A starting point may be the origin story of this weighty word.

Many Christians believe that humanity was expelled from paradise, but that the soul may be able to return to it in the afterlife. This ideology, which often conflates Heaven and the Garden of Eden, was not the first definition of paradise though. As Alessandro Scafi outlines in his book, Maps of Paradise, in the late second century B.C., “a term pointing to ‘paradise’ first emerged on the lips of the Medes, a powerful and, for us, enigmatic ancient tribe in the Middle East and central Asia.” Scafi goes on to say that, “a Median word, possibly ‘pari-daiza’, passed to the Persians to signify an enclosure. From pari-, meaning ‘around’, and daiza-, meaning ‘a wall made of a malleable substance’, such as clay, in ancient Iran the word stood for something surrounded by a wall.”1 Ultimately a version of ‘pari-daiza’ comes to be used in Persian to describe, “a hunting park for the enjoyment of the elite, especially kings.”2 What an incongruous beginning for what has become such an idealistic concept. Still, maybe it shouldn’t come as a surprise that historically, paradise has been considered either exclusive or unattainable in one’s lifetime.

Fast forward a few millennia and versions of this original definition of paradise continue to thrive in both words and pictures. By 1321 the Italian poet Dante Alighieri’s completes his three-part Divine Comedy in which readers travel with Dante through the Inferno and Purgatorio to reach the Paradiso. By 1667, the English poet John Milton pens an account of the Biblical story of the Fall of Man in Paradise Lost followed by the story of the temptation of Christ in Paradise Regained. During this same period, Western cartographers also attempt to identify the location of the Garden of Eden in elaborate maps, attempting to regain paradise as Milton did. Such maps, now considered examples of “persuasive cartography,”3 persist as late as 1855 with seductive names such as Paradise According to Three Different Hypotheses, The Ordering of Paradise, The Opportunity of Paradise, and Situation of the Terrestrial Paradise. Through these persuasive maps, classic works of literature, religious histories, and linguistic roots, a dominant conception of paradise does persist. However, there are still numerous graphic alternatives to explore. In fact, if you’re an artist, you may believe that paradise is the present; that it can be seen in any moment, anywhere.

This point leads me to the second commonly shared belief concerning paradise, namely, that paradise can be pictorially represented. This belief of course has been proliferated by a long lineage of imagemakers. Adam and Eve’s expulsion from paradise was a popular subject among Italian Renaissance painters. While many of those images withhold a full view of paradise, emphasizing loss, shame, and inaccessibility, we are still provided with a representation of it. Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch countered this trend in his infamous triptych, known as The Garden of Earthly Delights, where Eden, its ruin, and Hell are fully and vibrantly rendered. Interestingly, in this same era, paintings of earthly paradises emerge as well, usually consisting of verdant landscapes brimming with plant and animal life of all kinds. It is at this point that paradise becomes attainable, in the present moment, through the agency of artists.

Recalling the modern pictorial history of paradise is like reviewing a list of greatest hits from the Western canon. Depictions of a variety of paradises, Biblical and otherwise, flourish in paintings and drawings by William Blake, James Ensor, Salvador Dalí, Romare Bearden, Wassily Kandinsky, and Helen Frankenthaler, ebbing and flowing between realism and abstraction. Yet, the lineage stalls at the threshold of abstract expressionism and, seemingly, excludes photographic depictions. Such a finding raises a variety of questions: Is paradise still pictured today? And, assuming that it is, what does it look like? Can paradise be found in the world at hand? Can it be created? Can it be photographed? At least fourteen photographers consider these questions on the following pages and on the walls of The Southern Gallery of Contemporary Art in Charleston, South Carolina in Paradise Road | Paradise Out-Front.

If we look at the land we inhabit attentively enough, can it tell us something about the past, present, and future of America? Eliot Dudik asks this question in different ways in each of his recent projects. His most recent project, Paradise Road, comes pointedly on the heels of Broken Land, in which Dudik drove a total of 30,000 miles to survey Civil War battlefield sites in 26 states. His goal for this project was not however, historic preservation. By pointing to such a divisive period and to sites where some of our country’s most horrific conflicts played out, Dudik also points to the polarized American climate of today. Ultimately he hopes such a project might “derail that seemingly inevitable tendency for repetition.”4 At first glance, the peaceful, pastoral scenes presented in Broken Land seem to be a counterpoint to the death and destruction that took place on these very sites. That is, until you realize the panoramic images are constructed with two different negatives, simultaneously united and divided.

Paradise Road is just as pointed and just as subversive. This deceptively transparent title describes the actual location of every picture in the series. There are roughly 196 Paradise Roads in the continental United States and Dudik has photographed over 90 of these Paradise Roads to date. In describing his motivation for the project Dudik told me that he wanted to “drive to paradise and see what was there,” seeing this project as a means to “take the temperature of the country.” After all, what better way to understand the state of America than by surveying its paradises?

Paradise Road is then both a literal and allegorical investigation. It lives somewhere between the traditions of American road trip projects like Robert Frank’s The Americans or Alec Soth’s Sleeping by the Mississippi, and the conceptual typologies of Bernd and Hilla Becher. Ed Ruscha’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip might in fact be the closest relative to Paradise Road. Both projects depict and transcend exactly what is described in their titles, leaving ample room for meditation and projection. How does one begin to think about photographing the legacy of American exceptionalism in the wake of widespread economic, racial, and gender inequality? Visit enough Paradise Roads and it may all just play out before your eyes.

Two cows observe a farmer working on a broken down sedan on Paradise Road in Wittenberg, Wisconsin.

A cemetery and housing development at the edge of Zion National Park populate Paradise Road in Hurricane, Utah.

A narrow hillside divides a new high rise from a cleared field, now occupied by a pile of worn tires and a cluster of trailers on Paradise Road in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania.

A single mobile home with peeling mint green paint sits in a barren pasture behind a barbed wire fence on Paradise Road in Boulder, Wyoming.

The humor, the sadness, the EVERYTHING-ness and American-ness of these pictures!*

While Paradise Road lays out a lyric typology, it’s a specific one. In curating the exhibit Paradise Out-Front, Dudik zooms out to survey a constellation of paradise-related works by his peers. Despite the specificity of his own work, he provided only a spare prompt when inviting the selected artists to participate: “Send over a few jpegs that in your mind deal with the idea of paradise in some way or another. These can be literal, abstract, suggestive, counter-intuitive, whatever.” I’ve come to think of Dudik’s cryptic prompt as a sincere provocation given the aforementioned history of paradise and the current climate of present-day America. So, how do thirteen photographers working in this country in 2016 respond when asked to deal with the idea of paradise?

Aline Smithson and Ben Alper responded in opposition to traditional concepts of paradise. The title of Smithson’s works, Not as Interesting and Nothing to See, appear in the images themselves, overlaid across toned landscapes. Her lack of interest in “the rapture of Western topographies,” as she writes in her artist statement, is clear and Smithson’s candidness is refreshing. Alper is similarly uninterested, or just unable to consider an idyllic paradise given, as he states, “the state of the world, but more immediately the state of our country.” His Cocoon, Torso, and Tear (Building), are anxiety ridden but also signal transformation. What will ultimately come of that transformation is up to you.

Anastasia Samoylova, Frances Jakubek, and Mark Dorf responded to the paradise prompt skeptically providing a variety of composited images. Samoylova’s composite is sourced from a Google image search using the keyword ‘paradise.’ Her search yielded paradise as dictated by algorithm. The paradise that Google sees is a tropical one, much like conceptions of the Garden of Eden. It too is exclusionary though, as the pictures capture beach resorts and getaways that very few people ever reach. These illusive images are made tangible to create the final physical assemblage that is re-photographed. Dorf also mines the digital realm in his composited video, untitled56. In combining camera-generated and data-generated images of landscapes, he challenges viewers to questions the disparity between representations and acknowledge the limitations of representations of all kinds. Jakubek however, veers back into the realm of materiality to create her untitled works from the Carefully Omitted series. Paper ephemera from a bygone era are carefully arranged in these concrete poems, alluding to a network of interior paradises.

Bryan Schutmaat and Susan Worsham responded sincerely. Schutmaat’s image, Refuge, is surreally classical. Unabashedly referencing photographs by the likes of Ansel Adams in the twentieth century or William Henry Jackson in the nineteenth century, he clearly believes paradise can be found in this world. Worsham’s image, The Parrot Room, invokes a certain surrealism, but of the Southern variety. Only in the south could one find a sunroom inhabited by a wrought iron chair, potted plants, ripening fruit, duck decoys, a live parrot, and a marooned painting of a snow-covered Western landscape. Though most of these elements may have sat in place for years at a time, Worsham activates the space, and intervenes in it, to create her own domestic paradise.

Justin James Reed and Katherine Squier provide a dose of mysticism. Reed likens paradise to psychic conditions which can only be manifested in the presence of nature. Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote, “Every natural fact is a symbol of some spiritual fact.”4 His philosophy is played out in Reed’s associative images. I imagine the astral web of vegetation may be the vision that keeps that unnamed figure transfixed. Squier, too, attempts to elevate everyday apparitions. Here, focusing on elegantly outstretched limbs, it seems as if these obscured figures may be gatekeepers to paradise.

Ian Van Coller and Matt Eich acknowledge impermanence in their views of paradise. Van Coller’s portraits provide a closer look at what could be the next generation to inhabit Paradise Road. Though he doesn’t directly address the idea of paradise in his artist statement, his subject speaks for him. The formerly booming mining town of Butte, Montana clearly alludes to the fleeting nature of terrestrial paradise. Eich’s photographs speak to a corporal transience. In both Backyard Haircut and Side Exit we are presented with a family portrait and a tenuous façade. These images remind me that paradise isn’t always on a mountaintop or tropical island. Though inherently less permanent, home may be paradise, whether it consists of a house or not.

And finally, Thalassa Raasch and Jared Ragland have created their own paradises amid personal tragedy. Both have recently lost loved ones and decided to create opportunities to see paradise when they needed it most. Raasch’s images begin and end as physical monuments. Crafting handmade memorials in her own garden provides the opportunity to tangibly perform her grief and then document it. Ragland, struggling with a similar loss, looked toward the heavens instead of the earth, bringing us full circle. His series eequivalentss is a digital homage to Alfred Stieglitz’s series Equivalents and provides opportunities for prayer and meditation. By searching and photographing the sky for the duration of his mother’s battle with cancer, Ragland creates time and space to access paradise.

It appears I have, in the end, answered my own questions. Paradise is still pictured today. Paradise can be found in the world at hand. Paradise can be created and it can be photographed. There are an infinite number of paradises available to us if we look attentively.

Lisa McCarty

Curator of the Archive of Documentary Arts,

David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library,

Duke University

November 2016

NOTES

* Kerouac, Jack. Introduction. The Americans, by Robert Frank, Grove Press, 1959.

1 Scaifi, Alessandro. Maps of Paradise. University of Chicago Press, 2014.

2 Ibid.

3 Cornell University Library. The PJ Mode Collection of Persuasive Cartography, 2012, https://persuasivemaps.library.cornell.edu/. Accessed 15 November. 2016.

4 Dudik, Eliot. “Broken Land.” Lensculture, https://www.lensculture.com/projects/15204-broken-land. Accessed 20 November 2016.

5 Emerson, Ralph Waldo. Nature. James Munroe and Company, 1836.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Houston Center of Photography: THE VANGUARD,Rebel Girl, and Soft Heat…and a conversation with Anne MassoniMarch 12th, 2026

-

A Collaborative Photographic Exhibition by Heather and Ben Mattera: Weight of It AllMarch 7th, 2026

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Landscape ReEnvisioned Exhibition At the Monterey Museum of ArtFebruary 26th, 2026

-

Femina at Gallery 169February 20th, 2026