Arnold Newman Prize: Daniella Zalcman

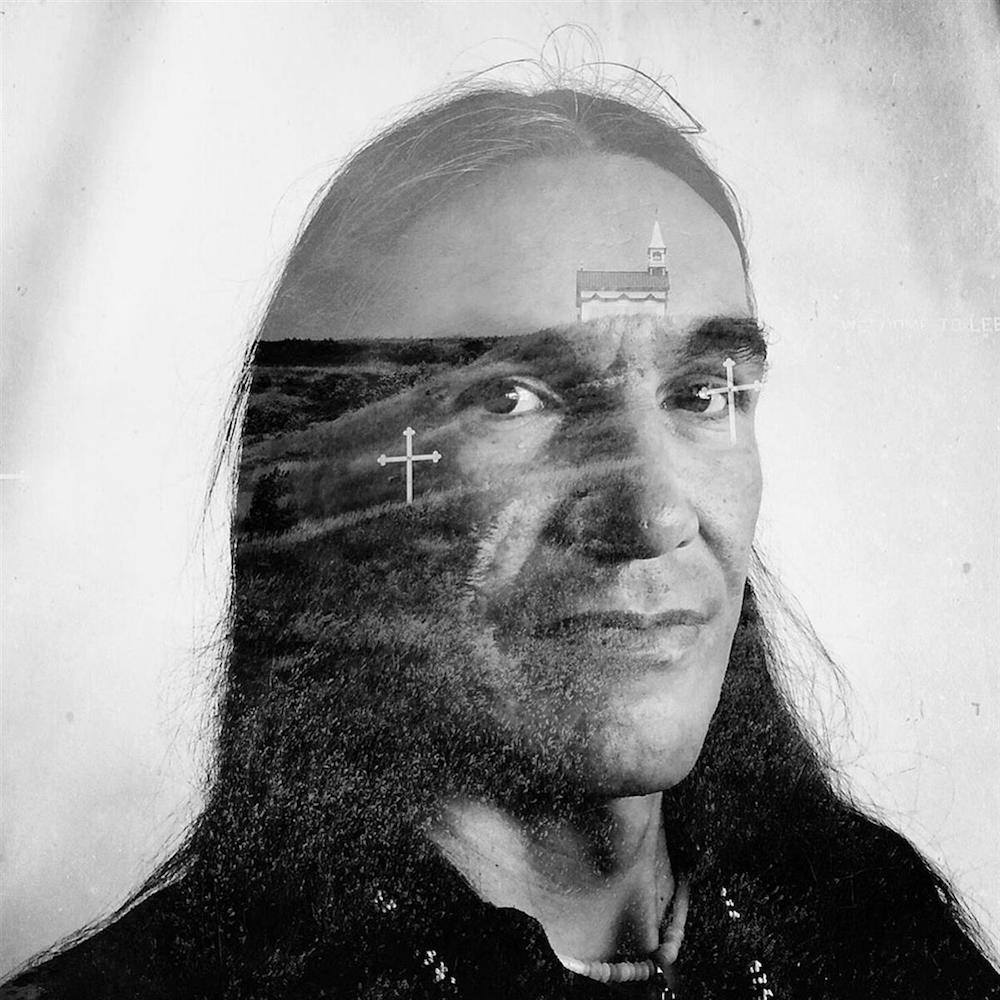

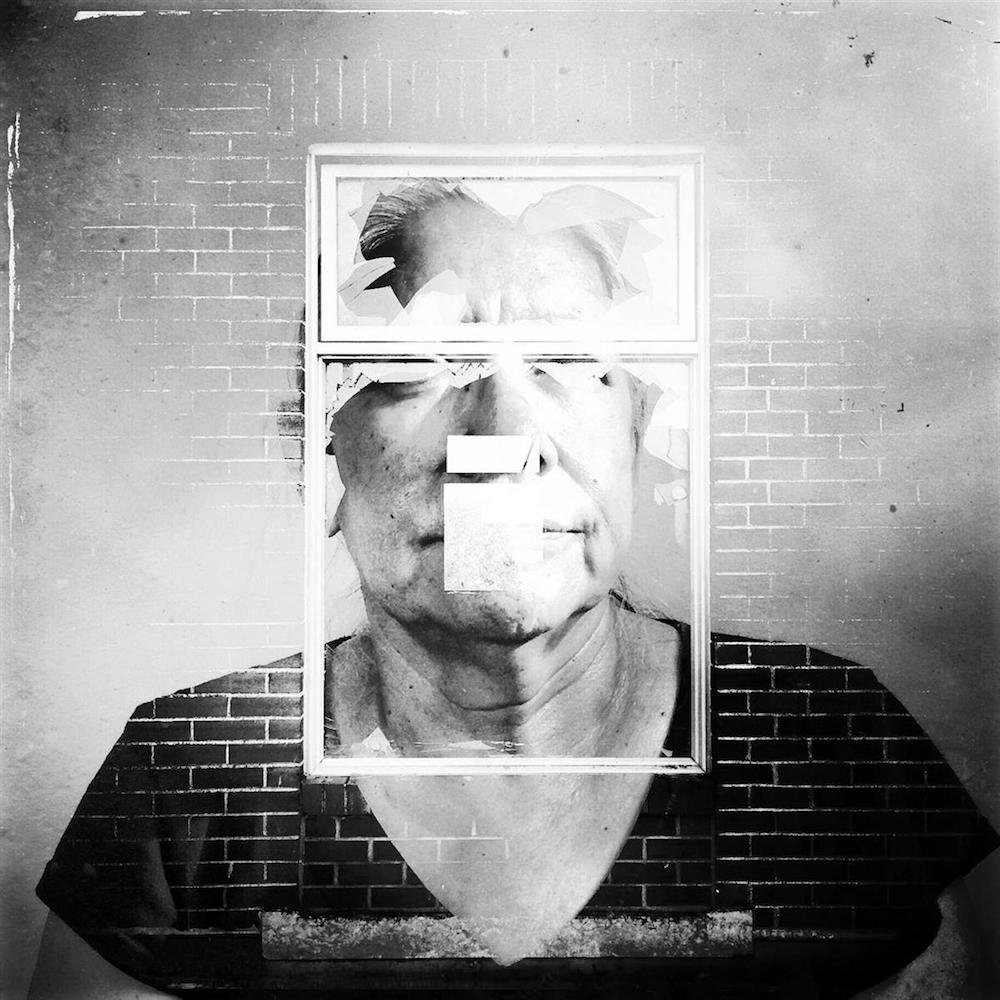

©Daniella Zalcman, Glen Ewenin, Muskowekwan Indian Residential School (1973-1975) “Residential school affects how you see the world. I can’t fit into the public anymore, I don’t feel like a normal person. … I don’t even notice myself teaching my kids to be afraid of authority. But it’s made me such a negative person. It changes everything.”

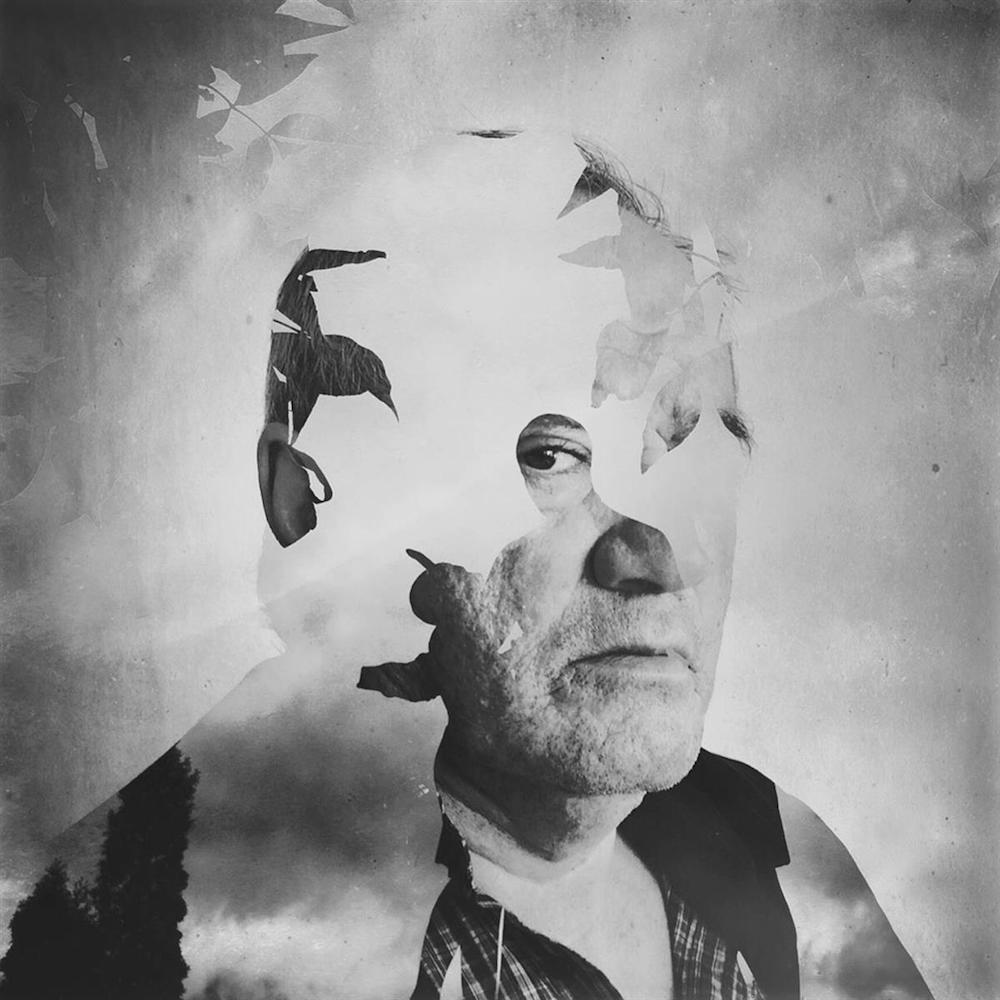

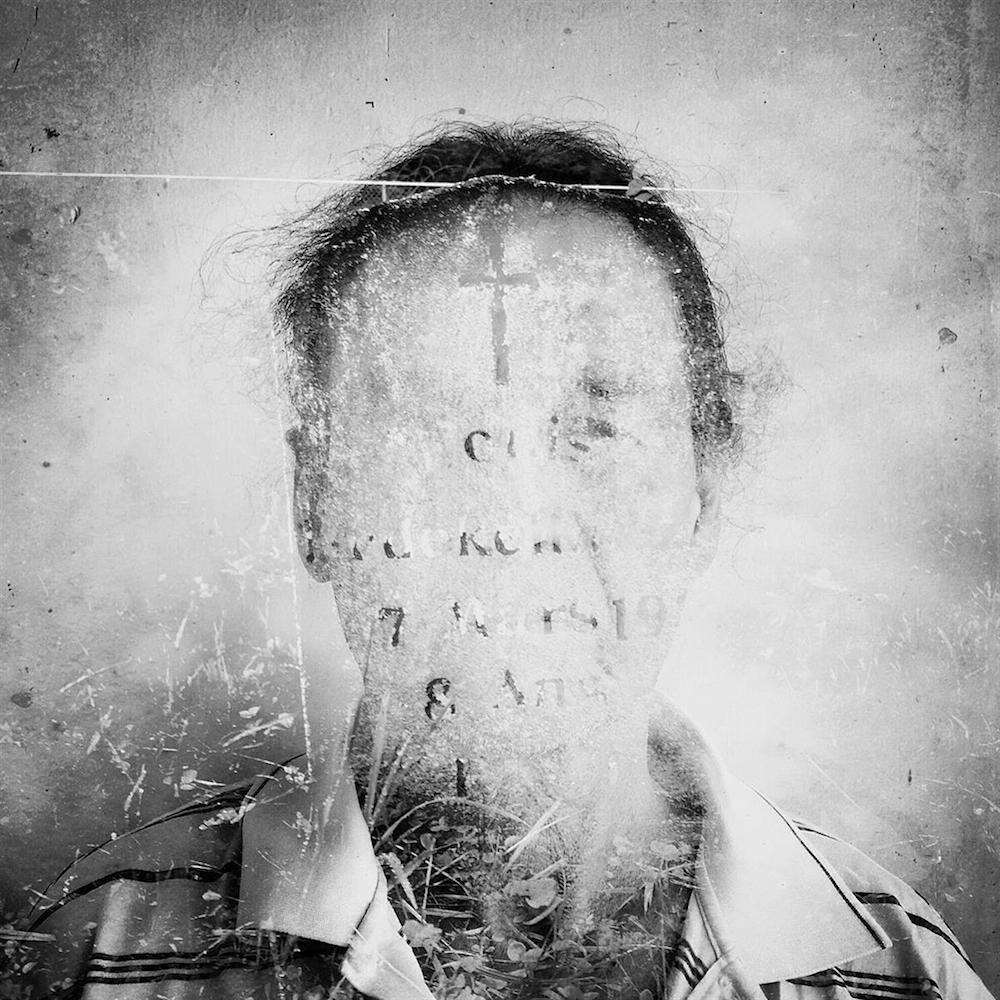

Daniella Zalcman is the 2017 Winner of the Arnold Newman Prize for New Directions in Photographic Portraiture. Her project, Signs of Your Identity, depicts survivors of Indian Residential Schools; each image is accompanied by a quote from the subject. This portfolio of 10 images covers victims in Canada and the United States. Zalcman is already working in Australia and plans to extend the project to various other countries that have iterations of residential schools that indigenous students were forced into. The project delves into the lasting trauma of these schools. She was recently named one of pdn’s 30.

The Arnold Newman Prize for New Directions in Photographic Portraiture was established in 2009 by the Arnold & Augusta Newman Foundation. The Prize is generously funded by the Arnold & Augusta Newman Foundation and proudly administered by Maine Media Workshops + College, where Arnold Newman taught for more than 30 years. The 2017 jurors included Philip Brookman, LaToya Ruby Frazier, and Jody Quon. Finalists were Sophie Barbasch for her project Fault Line, Daniel Coburn for his project The Hereditary Estate, and Jessica Eve Rattner for her project House of Charm.

The work I’ve shot so far over the past two years, mostly in Canada and the U.S., focuses on the impact of what it means to lose your identity. A disproportionate number of residential school survivors and their immediate family struggle with PTSD, depression, and substance abuse — and this persistent legacy of social and public health consequences needs to be documented and shared. I create multiple exposure portraits of former students still fighting to overcome the memories of their residential school experiences. These individuals are reflected in the sites where those schools once stood, in the government documents that enforced strategic assimilation, in the places where today, native people now struggle to access services that should be available to all Canadians and Americans. These are the echoes of trauma that remain even as the healing process begins.-Daniella Zalcman

Daniella Zalcman (b. 1986) is a documentary photographer based in London and New York. She is a multiple grantee of the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, a fellow with the International Women’s Media Foundation, and a member of Boreal Collective.

Her work tends to focus on the legacies of western colonization, from the rise of homophobia in East Africa to the forced assimilation education of indigenous children in North America. She won the 2016 FotoEvidence book award for her project Signs of Your Identity, which will be released this fall. She was recently named one of pdn’s 30 for 2017 and is the winner of the 2017 Arnold Newman Prize for New Directions in Photographic Portraiture.

Daniella’s work regularly appears in The Wall Street Journal, Mashable, the BBC, and CNN, among others. Her photos have been exhibited internationally, and she regularly lectures at universities and foundations. She graduated from Columbia University with a degree in architecture in 2009.

©Daniella Zalcman, Gary Edwards, Ile-a-la-Crosse Indian Residential School (1970-1973) St. Michael’s Indian Residential School (1974-1976) Qu’Appelle Indian Residential School (1976-1978) “I remember after mass every Monday, the head priest would set a large mason jar on the podium. He and two helpers would lock the church doors, and then put on those 1930s canister gas masks. Then they’d open the mason jars and just watch us. We never knew what was happening, but within a few minutes kids would start vomiting or twitching or foaming at the mouth. Looking back, I don’t know, but I think it was mustard gas.”

Signs of Your Identity

As Britain built an empire that would one day hold sway over a quarter of the world’s land surface, Parliament had to decide how to handle its new indigenous subjects. In an 1837 House of Commons Report, the government posited that the only way forward was imposing assimilation. In Canada, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand, various iterations of the Indian Residential School system were created — usually church-run boarding schools meant to forcibly assimilate indigenous children into Western culture. Attendance was mandatory, and Indian Agents would regularly visit aboriginal communities to take children as young as two or three from their homes. Many of them wouldn’t see their families again for the next decade, others would never reunite again. These students were punished for speaking their native languages or observing any indigenous traditions, routinely physically and sexually assaulted, and in some extreme instances subjected to medical experimentation and sterilization.

“‘You stupid Indian’ were the first English words I ever learned,” Tom Janvier told me. He was sent to Canadian residential school as a three-year-old, where he was bullied, beaten, and repeatedly sexually molested over a ten year period. “It became self-fulfilling. My identity was held against me.”

The removals continued in Australia until the 1970s. The last residential school in Canada didn’t close until 1996. The U.S. government still operates 59 Indian Boarding Schools today.

©Daniella Zalcman, Deedee Lerat, Marieval Indian Residential School 1967-1970 “When I was 8, Mormons swept across Saskatchewan. So I was taken out of residential school and sent to a Mormon foster home for five years. I’ve been told I’m going to hell so many times and in so many ways. Now I’m just scared of God.”

The lasting impact on these indigenous populations is immeasurable and grotesque. Thousands of children died while in the system — so many that it was common for residential schools to have their own cemeteries. In Canada, mass graves are being discovered on a near monthly basis. And those who did survive, deprived of their families and their own cultural identities, became part of a series of lost generations. Languages died out, sacred ceremonies were criminalized and suppressed. The Canadian government has officially termed the residential school system a cultural genocide.

©Daniella Zalcman, Grant Severight, St. Phillips Indian Residential School 1955-1964 “We as a people have normalized every conceivable dysfunction that we experienced in residential school. Negativity is transmitted — and if we don’t deal with it we pass it on. Even in school, kids who themselves were terrorized grew up to be abusers. We need to figure out how to heal from that.”

With the help of the Arnold Newman Prize, I hope to continue this multi-stage, multi-nation project by completing the U.S. chapter of this work. My next areas of focus are the Pacific Northwest (Coast Salish), Alaska (Inuit), the Northeast (Wabanaki), Midwest (Ojibwe), and Native Hawaiians. I also have plans to extend this project to Australia, New Zealand, Norway, Greenland, Colombia, and East Africa — all places that were home to coercive assimilation education systems.

Indigenous history continues to remain a footnote in our history textbooks, and in mainstream reporting. I hope this work will recast the stories that we are used to telling our children — about Pocahontas and Sacagawea and Columbus and Thanksgiving — and highlight the brutal history of cultural genocide. – Daniella Zalcman

©Daniella Zalcman, Mike Pinay, Qu’Appelle Indian Residential School 1953-1963 “It was the worst ten years of my life. I was away from my family from the age of 6 to 16. How do you learn about family? I didn’t know what love was. We weren’t even known by names back then. I was a number.” “Do you remember your number?” “73.”

©Daniella Zalcman, Rick Pelletier, Qu’Appelle Indian Residential School 1965-1966 “My parents came to visit and I told them I was being beaten. My teachers said that I had an active imagination, so they didn’t believe me at first. But after summer break they tried to take me back, and I cried and cried and cried. I ran away the first night, and when my grandparents went to take me back, I told them I’d keep running away, that I’d walk back to Regina if I had to. They believed me then.”

©Daniella Zalcman, Rosalie Sewap, Guy Hill Indian Residential School 1959-1969 “We had to pray every day and ask for forgiveness. But forgiveness for what? When I was 7 I started being abused by a priest and a nun. They’d come around after dark with a flashlight and would take away one of the little girls almost every night. … You never really heal from that. I turned into an alcoholic and it’s taken me a long time to escape that. I can’t forgive them. Never.”

©Daniella Zalcman, Selina Brittain, Marieval Indian Residential School 1954-1962 “I believe that they thought they were teaching us. I believe that they thought that assimilating us into their way of life would help us. But they changed us into something we weren’t — and there was nothing wrong with our way of life before. That’s what they still don’t understand.”

©Daniella Zalcman, Valerie Ewenin, Muskowekwan Indian Residential School 1965-1971 “I was brought up believing in the nature ways, burning sweetgrass, speaking Cree. And then I went to residential school and all that was taken away from me. And then later on, I forgot it, too, and that was even worse.”

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Lorraine Turci: The Resilience of the CrowMarch 16th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Awards: Natalia Garbu: Moldova LookbookMarch 15th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Rayito Flores Pelcastre: Chirping of CricketsMarch 14th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Alena Grom: Stolen SpringMarch 13th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Louise Amelie: What Does Migration Mean for those who Stay BehindMarch 12th, 2024