Michelle Van Parys: The States Project: South Carolina

Michelle Van Parys is a beacon in our photographic community here in South Carolina. To say Michelle is hardworking would be an understatement. She built the photo program twenty years ago at the College of Charleston, hired the leading darkroom architect to outfit a workspace for her students, and continues to run her own show all the while making work, publishing and teaching.

She is known as a dedicated professor who “considers the work of her students deeply,” accessible to everyone and always up for you to pop by if you are in town, and I would have to add a very thoughtful colleague and friend.

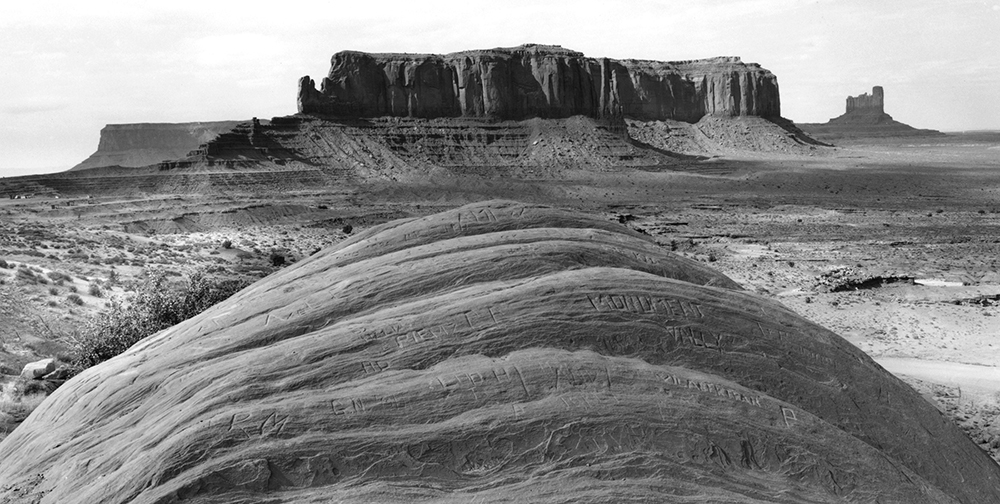

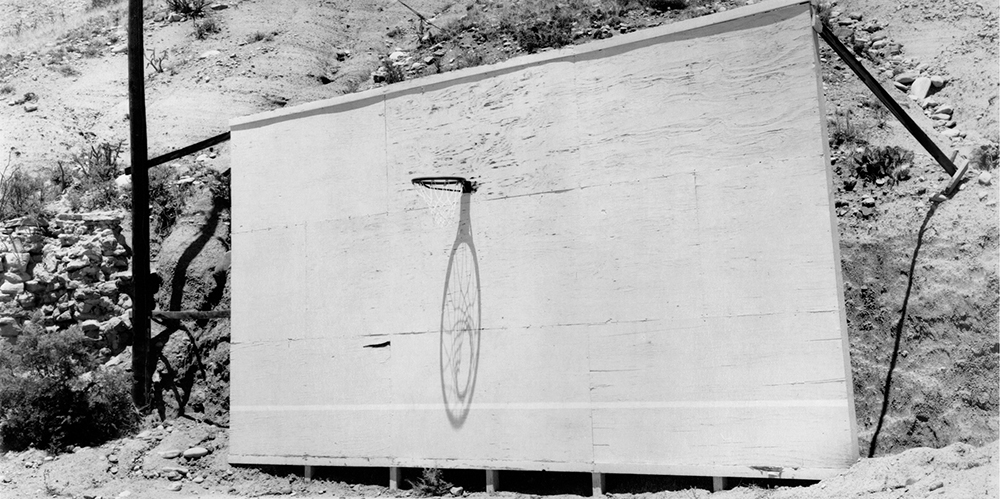

Her work in The Way Out West and Beyond the Plantations is in many ways a reflection of her sophistication as an artist—the images are weighted with history and immediacy, move between the serious and lighthearted, and express control and the inevitability of our interaction with the landscape.

Michelle Van Parys was born in Arlington, Virginia. She is a Professor at the College of Charleston in the Studio Art Department where she started the photography program in 1996. Michelle received her B.F.A. from the Corcoran School of Art in Washington D.C, and her M.F.A. in Photography from Virginia Commonwealth University. Her photographs have been exhibited internationally in solo and group exhibitions. A monograph of her photographs entitled The Way Out West: Desert Landscapes was published in 2009 by the Center for American Places at Columbia College Chicago.

Michelle Van Parys has been the recipient of the Virginia Museum Fellowship and the South Carolina Arts Commission Fellowship. Her photographs are included in several museum collections such as the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The High Museum, the Virginia Museum of Fine Art, and the Portland Art Museum.

The Way Out West

Through my landscape photographs I look to reveal the various cultural strata, both obvious and subtle, inscribed within. I am interested in conveying a sense of local distinctiveness as well as the diversity of these regions. In this sense, my photographs are conceived as open-ended meditations on evolving human/nature interactions.

I started The Way Out West series in 1986 while living in San Francisco. This series charts my response to the Southwest landscapes in which humans have insinuated themselves. Specifically, I juxtapose nineteenth century art historical notions of the sublime landscape with the ways in which we live on the land today, and thereby to draw attention to our uneasy alliance with the natural world. Through this work I attempt to present a range of possibilities for these interactions. At times we appear oppositional and destructive and at other times harmonious and custodial. I am interested in the myriad forms this relationship takes: humorous, ironic, dangerous, and fatalistic, to list a few. The frame of the camera allows me to isolate and organize elements in the landscape that reflect our complex interactions with the land.

After moving to Charleston, South Carolina in 1994 I started to photograph the surrounding region known as the Lowcountry. The photographs from Beyond the Plantations: Images of the New South present the contemporary southern landscape with same conceptual framework that I used in my western landscapes. I see the landscape as dynamic representation of the complex relationship we have with our surroundings over time. It is the accumulation of layers of human trace within this verdant landscape that drives this series of photographs. These images are offered in contrast to the idealized or romanticized landscapes that are often illustrated in depictions of the south through literature, cinema, or visual art. Images of the Old South are often sanitized views of a perfect and prosperous plantation life yet ignore the conflict, conquest, and transformation that is manifested in the changing landscape. The photographs from Beyond the Plantations incorporate the physical beauty of the landscape within the context of its longstanding complexities and contradictions.

Photographing the West and then the South–what a stunning visual leap–both expansive yet singular. I have no doubt the sensory experience of photographing was quite distinct as well. What common ground have you found in the process of making these two projects?

The transition from photographing in the West to the South was much more difficult than I ever imagined. It literally took me years to make the transition. When I started to photograph in the Low country I kept looking for wide-open spaces and a horizon. I was looking for places without so many trees and dense foliage. I was also looking for places without so many dark shadows. In my western images the tones are very high-key, in the south the tones are more low-key. Once I realized that I was looking for something that does not exist I started to see what was in front of my eyes all along. I then had to find the right balance of exposure and development of the film so that I could maintain the detail in the shadows without losing the highlight details. The common ground, or the thread that links my two bodies of work, is the conceptual framework of my landscape images. The camera allows me to isolate and organize elements in the landscape that reflect our complex interactions with our surroundings. In my landscape photographs I look to juxtapose the sublime natural landscape with traces of human presence. I am interested in showing how the landscape changes over time, and how this change often goes unnoticed.

Have you returned to some of these places? Ever thought of returning, most especially in The Way Out West series, to see if a shift has taken place in your response to these spaces?

I have returned to many of the sites where I photographed in the West. Since the photographs from The Way Out West were taken over a twenty year time frame I have seen how these places have changed. I think that the images from my last photographic expedition to the West were a bit more polemical. I was looking at the explosion of development in southern Nevada in 2006, and could not avoid commenting on the absurd logic of building an even bigger city in a desert that is already depleted of water. At time it looked like there were no limits to the development surrounding Las Vegas. It would be interesting to return to that part of Nevada now. I wonder how the economic downturn in 2008 has impacted that area?

Your book The Way Out West is exquisite. The sequence is powerful and every image has a unique purpose in this desert narrative you weave for us. What was the process like for you?

The process of publishing a book was a lesson in patience. Before the Center for American Places agreed to publish The Way Out West I had two contracts with academic publishers. With each press I had a signed contract and worked closely with an editor. Each time the editor left the publisher and my book contract was dropped. This put the book in limbo for over 4 years. I started to think that I would never have a book published of this work. However, during this time I continued to make new images for the series. In hindsight I am glad that the book did not get published sooner than it did. The project is much more complex now. Working with George Thompson, the editor and publisher for the Center for American Places, was a great learning experience for me. George had a clear vision for the book. Through his selections and sequencing of the images I began to see connections that had not been apparent to me. That in itself was an invaluable experience for me, as it would be for any artist.

What piece of literature would you say has most influenced or fueled the making of imagery in Beyond the Plantations?

I don’t have one piece of literature that I can point to that has influenced my images in Beyond the Plantations: Images of the New South. This series of photographs is in stark contrast to the idealized or romanticized landscapes that are often illustrated in depictions of the south through literature, cinema, or visual art. Images of the Old South are often mythologized views of a “picture perfect” landscape.

Art critic and theorist Lucy Lippard’s book The Lure of the Local has been a significant influence on my work. In the introduction to this book she states “Artists can make the connections visible. They can guide us through sensuous kinesthetic responses to topography, lead us from archeology and land-based social history into alternative relationships to place. They can expose the social agendas that have formed the land, bring out multiple readings of places that mean different things to different people at different times rather than merely reflecting some of their beauty back into the marketplace or the living room.”

What is on the horizon?

I continue to make new images for Beyond the Plantations: Images of the New South. My goal is to publish a book on this series of images. I am also working on a collaborative project with an Edgar Allan Poe scholar about the “afterlife” of Poe in the cities where he lived and worked.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jen Ervin: The States Project: South CarolinaJuly 22nd, 2017

-

Michelle Van Parys: The States Project: South CarolinaJuly 21st, 2017

-

John Lusk Hathaway: The States Project: South CarolinaJuly 20th, 2017

-

Ashley Kauschinger: The States Project: South CarolinaJuly 19th, 2017

-

Tracy Fish: The States Project: South CarolinaJuly 18th, 2017