Alyssa Schukar: The Most Industrialized City

©Alyssa Schukar, American industry disproportionately affects the health of minority and low-income communities, and East Chicago, Ind. — known as the country’s “most industrialized municipality” during the Industrial Revolution — offers a view of environmental injustices emerging throughout the Rust Belt. ||| BP expanded its refinery to the northern boundary of Marktown, a 100-year-old workers village in East Chicago, in 2013. Well within a disaster blast zone, the neighborhood is a liability for BP. The firm has offered between $4,545 and $30,000 for the properties, which is not enough to buy an equivalent home, especially on a fixed income. Residents say they have felt more vulnerable with each of the nearly 20 buildings demolished in the past year. Many homeowners, including some whose families have lived in the neighborhood for four or five generations, are rallying to save Marktown, though the steel and oil industries’ pollution continues to plague their health. Tar sands oil production is a particularly dirty process, and after the plant expansion, the refinery is more than tripling its output of petcoke to 2.2 million tons a year. And though the steel industry employs fewer people now than fifty years ago, its productivity has increased. East Chicago air tests among the state’s highest in levels of cadmium, lead and other airborne toxins.

I had the pleasure to meet documentary photographer, Alyssa Schukar on my last visit to Chicago when I was teaching a workshop for Filter Photo. Alyssa is a devoted observer who has traveled the globe to tell her stories and has the ability to put significant issues into context. One of her current project, The Most Industrialized City, is closer to home. Her photographs weave daily life with daily concern, showing us a vibrant community living in a toxic environment.

Alyssa Schukar is an independent, documentary photographer based in Chicago who also teaches at Columbia College Chicago. In her personal work, she is interested in examining how our surroundings shape our communities and individual experiences. She has worked extensively in East Chicago, Indiana, which was recently honored with Cliff Edom’s “New America Award.” Throughout her career, she plans to document the effects that environmental inequities have on communities.

“I’m grateful to share the stories of people I meet. I spent the first five years of my career on staff at a newspaper in the Great Plains where I traveled extensively on documentary and portrait assignments. I also spent two months reporting daily during a military embed in Afghanistan. On the job, I learned how to earn people’s trust and document their lives with empathy”.

World Press Photo, Pictures of the Year International and the National Press Photographers Association have honored her work, and in 2014, Alyssa Schukar was named the Great Plains Photographer of the Year. In 2016, she participated in the New York Times Portfolio Review. This year, she will lead two photographic workshops and take part in Review Santa Fe.

©Alyssa Schukar, Taylor Collins, 11, lifts her 5-year-old sister Chloie up to an ice cream truck so she can choose her dessert as their sister Gianna, 6, at left, watches. Marktown, an East Chicago neighborhood, is bordered by steel mills and a British Petroleum refinery, seen at back. |||| American industry disproportionately affects the health of minority and low-income communities, and East Chicago, Ind. — known as the country’s “most industrialized municipality” during the Industrial Revolution — offers a view of environmental injustices emerging throughout the Rust Belt.

©Alyssa Schukar, Near BP’s refinery in Whiting, leaked oil sits on the surface of the Indiana Harbor and Ship Canal, which feeds into Lake Michigan.

In December, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency acknowledged that some of the city’s drinking water also contains high levels of lead, prompting Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb to declare a “disaster emergency” for the 322-acre site.

In a July 2016 letter to residents, East Chicago Mayor Anthony Copeland wrote, “your health and safety are always my first priority.” But nearly 80 percent of East Chicago’s 11 square miles is zoned for heavy industry, and many renters and homeowners say they no longer trust the government for basic services.Two miles north of Walker’s home lies Marktown, an East Chicago neighborhood on the National Register of Historic Places. Built to resemble an English countryside village, the century-old workers’ community is vanishing. British Petroleum is buying and demolishing the homes that its massive oil refinery surrounds.The refinery also pollutes the air and nearby Lake Michigan. Every year, BP’s refinery spits out 2.2 million tons of petcoke, black dust linked to higher rates of cancer and respiratory problems.President Donald Trump has proposed a 31 percent cut to the EPA, including its environmental justice program, which reduces the burden of pollution on low-income communities like East Chicago. Lead cleanups, environmental protection enforcements and restoration projects are expected to be cut back or abandoned.

Still, East Chicagoans are intensely proud of their community. Life endures within a system that profits at the expense of underrepresented people in disregarded spaces.

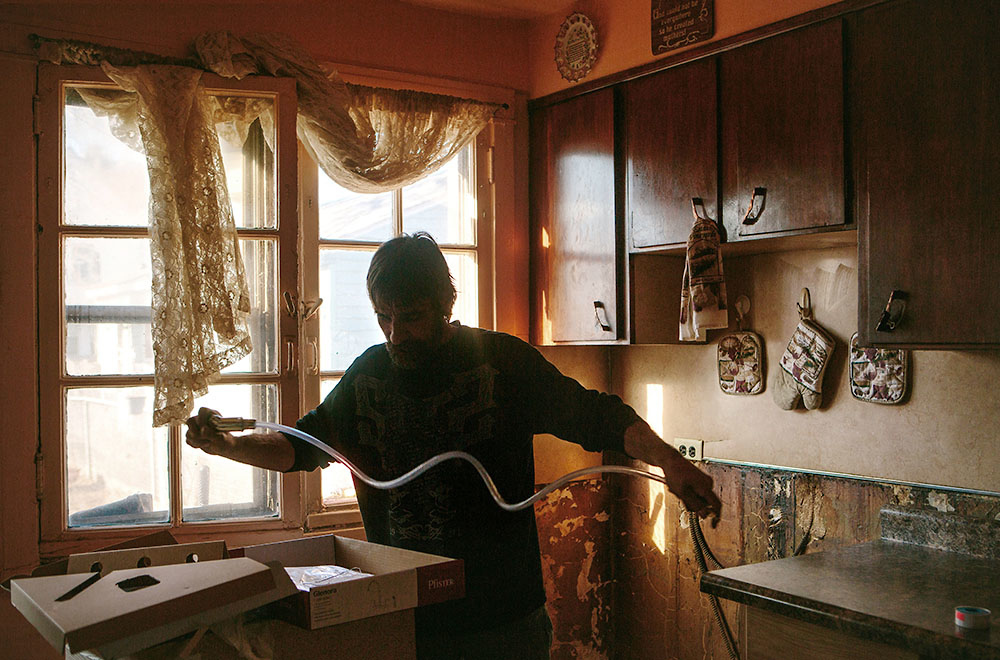

©Alyssa Schukar, Though the home’s future is uncertain, Michael Unger installs a new sink and cabinets in the kitchen of his childhood home where he lives with his sister Kim Rodriguez.

©Alyssa Schukar, A mile and a half from the Marktown neighborhood, Happy Jacks Liquors in Whiting is one of the few stores within walking distance of the neighborhood.

©Alyssa Schukar, Sand covers a dead migratory bird along the shore of Lake Michigan. The cause of the death is unknown, though much flora and fauna suffered after a malfunction occurred at the BP Whiting Oil Refinery a month earlier. At least 15 barrels of crude oil spilled into the lake.

©Alyssa Schukar, Lamont Anderson embraces his son Lamont Anderson Jr., 8, whose blood tested for lead poisoning. After living in the West Calumet Housing Complex for more than a decade, the family moved to Gary, Indiana earlier in the summer.

©Alyssa Schukar, Michael Unger rests alongside a collection of My Little Pony dolls, which his niece Leilany Rodriguez placed in the wheel well of a family vehicle.

©Alyssa Schukar, From left, friends since childhood, Janae Peyton, 13, Ashanti France, 12, Irene Wooley, 13, and Tniyah Foxx, 12, swing at the park near the West Calumet Housing Complex in East Chicago, Indiana. The playground is part of the Carrie Gosch Elementary School, which has been turned into an EPA office. “All my memories are here. I’ve got to move away from my friends,” Peyton said.

©Alyssa Schukar, The Indiana Harbor and Ship Canal, the largest integrated steelmaking facility in North America, juts out into Lake Michigan and lays 20 miles southeast of Chicago. The peninsula is completely manmade, using landfill and industrial byproduct for its foundation.

©Alyssa Schukar, TTatianna Muñoz poses for a portrait during her quinceañera at Club Ki Yowga in East Chicago, Indiana.

©Alyssa Schukar, BP expanded its refinery to the northern boundary of Marktown, a 100-year-old workers village in East Chicago, in 2013. Well within a disaster blast zone, the neighborhood is a liability for BP. The firm has offered between $4,545 and $30,000 for the properties, which is not enough to buy an equivalent home, especially on a fixed income. Residents say they have felt more vulnerable with each of the nearly 20 buildings demolished in the past year. Many homeowners, including some whose families have lived in the neighborhood for four or five generations, are rallying to save Marktown, though the steel and oil industriesí pollution continues to plague their health. Tar sands oil production is a particularly dirty process, and after the plant expansion, the refinery is more than tripling its output of petcoke to 2.2 million tons a year. And though the steel industry employs fewer people now than fifty years ago, its productivity has increased. East Chicago air tests among the stateís highest in levels of cadmium, lead and other airborne toxins.

©Alyssa Schukar, Logan Anderson, 19 months, plays with his brother Lamont Anderson Jr., 8, whose blood tested for lead poisoning. After living in the West Calumet Housing Complex for more than a decade, the family moved to Gary, Indiana earlier in the summer.

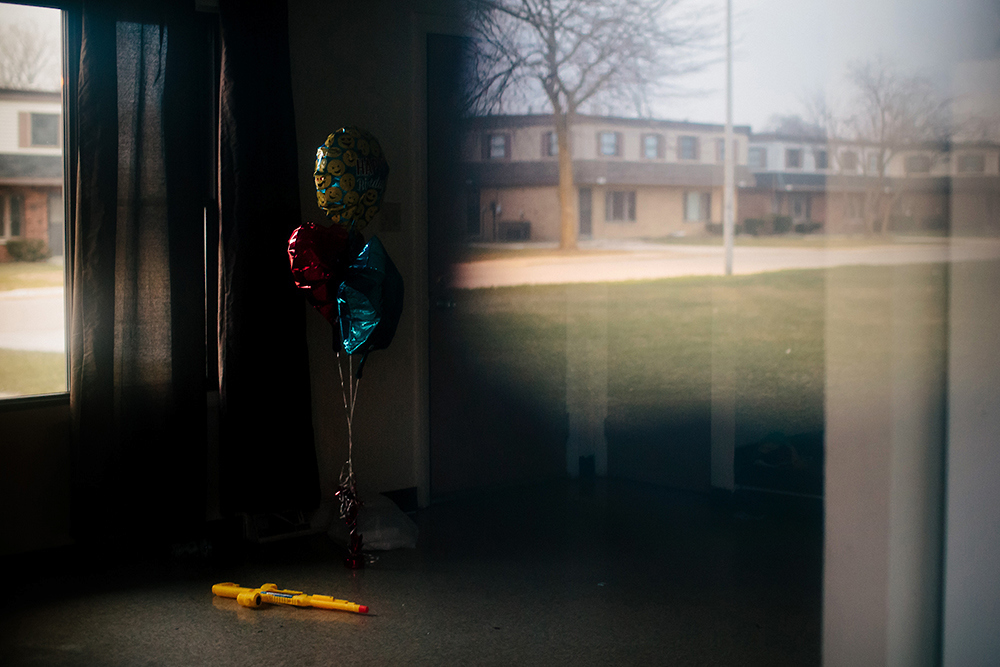

©Alyssa Schukar, Balloons and toys remain in an abandoned West Calumet Housing Complex home. In July 2016, nearly 1,200 people in the West Calumet neighborhood learned that children had blood-lead levels six times the Center for Disease Controlís recommendation for intervention. As mandated, residents began to move, but some remain as they struggle to find housing in the city of 29,000.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026