A Spotlight on the Black Crown Gallery in Oakland, CA

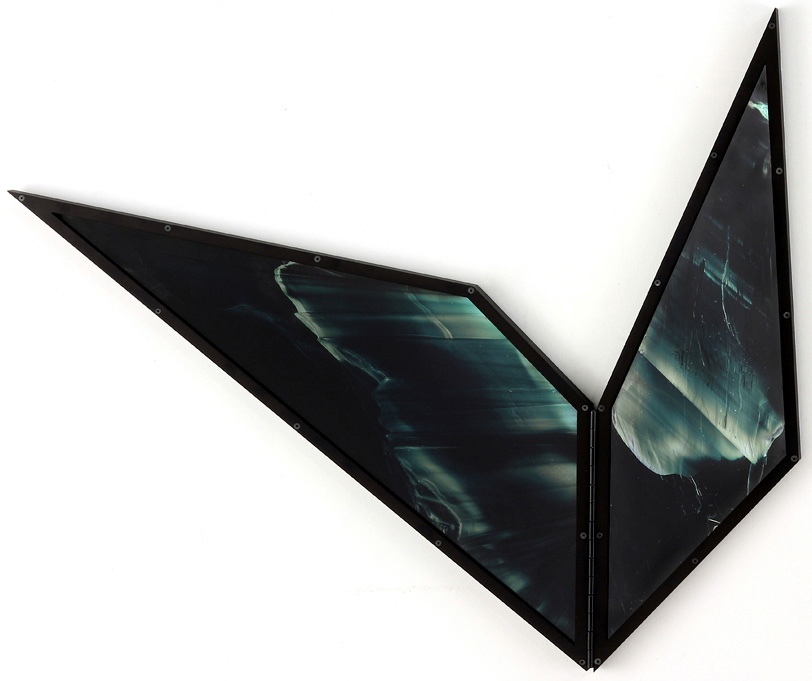

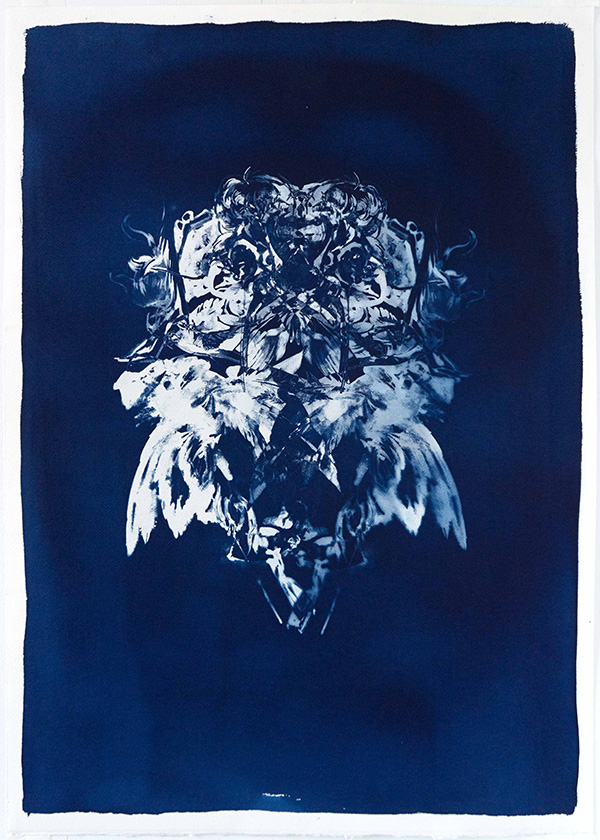

©Maggie Preston, Templates and ©Phillip Maisel, For Your “Open”, from the exhibition, Surface Tension

It’s always a pleasure to shine a light on a new gallery and Kim Beil, a Bay Area-based arts writer and lecturer at Stanford, spotlights Black Crown Gallery, a new gallery in Oakland, CA, co-directed by Christopher Nickel and Chrissy Cano. Nickel has a BFA in photography from the California College of the Arts (CCA) and an MFA from Stanford University. Cano has a BA in History from UC Berkeley and a BA in Visual Studies from CCA. In a little less than a year, the Gallery’s program has already featured a diverse range of artists, showing photography, sculpture, drawing, and inter-media work, united by sustained engagement in the processes and pleasures of embodied perception. What follows is an edited transcript of a conversation with Christopher Nickel, Chrissy Cano and Kim Beil.

Kim states: I was immediately taken with this new space in Oakland, not only because Black Crown Gallery was showing the work of one of my favorite Bay Area artists, Phillip Maisel, but because they were doing so in such a compelling way. The pairing of Maisel’s cut, collaged, and re-photographed work with Maggie Preston’s photographs and laser-cut steel sculpture revealed new things to me in each artist’s work. Exploring the gallery in the company of Nickel and Cano is a real pleasure; their conversation is wide-ranging and lively, their commitment to art and community invigorating. I hope this transcript conveys some of the energy of being in Black Crown Gallery and inspires readers to visit the Oakland space in person.

©Maggie Preston, Templates and ©Phillip Maisel, For Your “Open”, from the exhibition, Surface Tension

Kim: How have your varied backgrounds in the arts — as an arts practitioner and a historian of visual culture — influenced your work at the gallery?

Chris: In addition to having pursued a career in art, being an art viewer is important to who I am as an individual and how I interact with the world. A lot of my interest in the gallery stems from my experience at Stanford with artists who are working across disciplines [during the MFA] or at least have research interests that cross traditional boundaries of disciplines.

Chrissy: The artists that we’ve been drawn to have strong researched-based practices. There’s so much to look at and talk about and think about before the final product comes on the scene. You often don’t get any of that when you walk into a gallery. Getting to learn about the artist’s whole practice is intriguing to both of us, not just what you see in the end.

Kim: How much of this background do you allow into the gallery? How do you determine what information shares space with the work?

Chris: It’s a delicate balance. As a viewer, I always chafe at information being presented in a gallery that somehow dictates what I’m supposed to feel or how I’m supposed to react. We try very hard to walk a line of informing viewers without dictating their experience. We want to honor the research that the artists do and the complexity and diversity of their practices, but we don’t want to weigh viewers down with too much detail.

Chrissy: Sometimes artists don’t want to reveal very much about their process; they want to maintain an element of mystery. We always try to respect the desires of the artists we’re working with, but we are also knowledgeable about their practices so that when visitors ask questions, we can answer them.

Chris: We talk a lot with people in the gallery about what’s coming up next; this gives us a chance to see what people want to know more about, what they seem to think is unimportant, and that’s a good barometer for what’s worth emphasizing or what seems extraneous.

Kim: The value of local galleries is often accepted as a foregone conclusion. Could you describe how this has been useful to you, as an artist, to have a gallery that shows work close to where you live?

Chris: A high percentage of people who come into the gallery are artists and work or live nearby. They’re happy to see something in their neighborhood that represents their interests since it allows them to invite people into an aspect of their lives that might be invisible to those not otherwise involved in the arts. So, this is an opportunity for people to integrate their art life into their broader life.

Kim: What does it bring to your life, specifically, to have a place to talk about art?

Chris: It gives me a way of breaking apart from my routine and allows a slower, more careful contemplation. It’s a focus and attentiveness that isn’t afforded to us in our daily lives.

Chrissy: It also gives us an opportunity to interact with the creative community more regularly. We have studio visits, incredible conversations with artists and other professionals in the field. We’re starting to create a place of conversation.

Chris: For us personally, and others who’re engaged in the arts, the gallery is an opportunity to meet people, names that you hear frequently but don’t really have a face to put with them. I’ve meet a lot of wonderful people who’ve been on the periphery of my experience in the art world, and I’m happy to have direct contact with them now and to put them in touch with each other.

Kim: Physical space is important for the work that you show, too. You’ve described the work currently on view (Phillip Maisel and Maggie Preston) as art that needs to be seen in person. Is that a deliberate through-line of the artists you’re showing?

Chris: This isn’t something we intentionally seek out, but we are both excited by work that reveals itself after close inspection: when you’re able to see the texture or the depth, and it’s visible only by being in front of it in person. I think that’s very exciting and I feel most rewarded for going to see this kind of work. This is a consistent theme, but it’s not that conscious in terms of the way we choose the work.

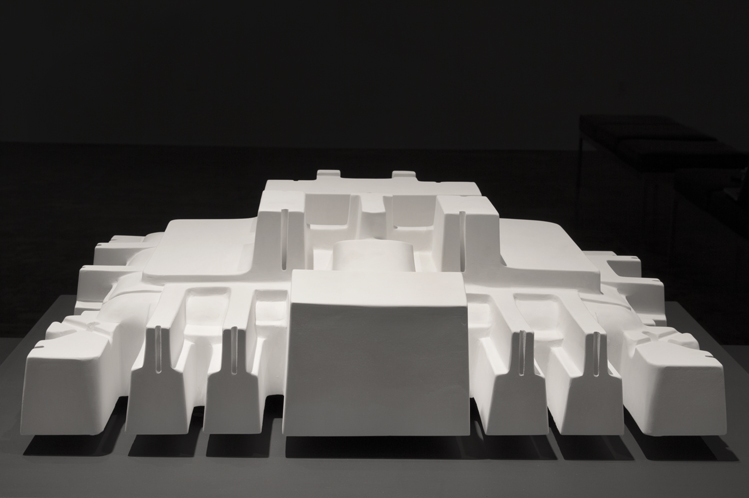

Chrissy: We have a physical space, so we have the opportunity to show art that doesn’t translate well onto a screen. For example, Kate Nichols: it’s hard to really see her work online, but in person it is spectacular. So much of the art world is moving onto online platforms that don’t necessarily do all work justice.

Chris: To get everything out of Kate’s work, you actually have to move in front of it. A series that stands out strongly in this regard is one that utilizes a silver-nanoparticle based paint which she developed during a six-year residency in a physics lab at Berkeley. The paint she invented doesn’t actually have any color inherent to it; rather it’s the way that it interacts with light that determines its observed color. It’s similar structurally to a fish scale or butterfly wing. She applies this paint to sheets of glass and backs them with black so that the iridescent quality is heightened—especially so as you change your position relative to the pieces.

With Phil Maisel’s work, he’s done this beautifully subtle thing, where the photographs are now mounted onto boards and the boards are painted on the edges to match the tones in the print. This is something that almost impossible to see on a screen, because the boards are only a quarter of an inch thick. There’s this bending-of-space illusion that occurs–or, really it’s not an illusion, it’s a reality.

Chrissy: And, they’re not just flat photographs, Phil uses a collage of images, like puzzle pieces that fit together…

Chris: Or an “inlay”?

Chrissy: Right, these are really inlaid photographs. It’s so exciting for us to watch as viewers have that moment of realization, when they see that there are layers to this work or that there are bits that come off the surface, in different materials. You don’t get that sense of dimensionality when you look at an Instagram shot.

Chris: There’s something about the scale of Phil’s work, too. The larger pieces fill your field of vision and really draw you into depth of the space that he’s photographing. Almost universally, people come into the gallery and do this kind of squinting thing. There’s this very effective illusion that happens between the surface of the materials he’s photographing, the depth of the image and the surface of the print. It gets very confusing and it forces people to spend some time in front of the image and then people start to see the details that Chrissy’s talking about. They see the seams and the cuts in the paper, contrasted against the seams that appear in the image of the set that he’s created and photographed. So, it’s the illusion of depth versus the reality of the surface, combined with the reality of the depth of the painted edges and all of that becomes a part of looking at the piece–and it’s really the content of the piece as well. All of that would be lost unless you’re seeing it in person and able to see all these fine details.

A similar thing is happening in Maggie’s work as well. At a certain distance the sculptures function in a certain way, they create an illusion of moving through space and being three dimensional and then as you get closer you think they’re completely flat, then when you’re even closer you realize that they do have depth. This illusion between depth and flatness varies depending on where you are relative to the piece. It’s dependent also upon the scale at which she’s created these sculptures, which you can see best in person.

Chrissy: Maggie’s forms all began as photographs on paper, but then they’re translated into three dimensions. So, being able to show the sculptures together with the photographs gives viewers a sense of the transition in the work from flat to having dimensionality.

Chris: We’re going back and forth between solo and two-person shows. We’re looking for work that can exist on its own but can also inform the way viewers look at the other work in a two-person show. Some pieces almost establish a criteria for looking at the other work. Hopefully, it’s a different way of looking than viewers might bring on their own, without the two artists combined.

Kim: Are there any guiding principles for the space of the gallery itself?

Chrissy: We didn’t want to be another bright, white box gallery. We wanted to be as welcoming as possible and that extends into the space itself, which isn’t perfectly sterile. There’s warmer lighting, there’s an intent to make it a more comfortable space. We have concrete on the walls and a raw wood ceiling. There are some architectural obstacles, but that’s part of the charm of working in an 1870s building.

Kim: What’s the significance of the name “Black Crown Gallery”?

Chrissy: Black crown night herons roost in the trees around the gallery. They’re a very popular bird here in the city of Oakland and we wanted to honor them and their place in the neighborhood.

Chris: The gallery is just two blocks away from Lake Merritt, which is one of North America’s largest urban bird refuges. There are literally dozens, if not hundreds, of species of birds that spend part of the year at the Lake. The night heron is different from other herons, in that it tucks its neck in when it stands, then stretches out when it flies, so if you see one take off, it’s a really shocking transformation, they kind of unfold in space.

Chrissy: [laughing] It’s a metaphor for the gallery….

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

The Next Generation and the Future of PhotographyDecember 31st, 2025

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Celebrating Vintage Analog PhotoboothsNovember 12th, 2025