Western Canada: Kyler Zeleny

Kyler Zeleny is a very busy individual, currently working towards his doctoral degree, has published multiple books and academic journals including Pocket Books and Imaginations, and continues to create conversation and community in areas that are unique and unspoken for. One of these territories that Kyler has spent years researching is the colonization of Western Canada and it’s progression into the present. Happening at the very end of an era, the land was built under the radar of history, and is survived by a specific type of people that still thrive in the area. Kyler’s body of work Crown Ditch and the Prairie Castle navigates this landscape and continues to help define the “on the road” genre that has been monopolized by American photography.

Kyler Zeleny (1988) is a Canadian photographer-researcher and author of Out West (2014) and Found Polaroids (2017). His current research interests deal with contemporary rural issues and how geography extends identity and creates community. His personal interests are in found photography, family albums and the politics of archives. He received his bachelors in Political Science from the University of Alberta and his masters from Goldsmiths College, University of London, in Photography and Urban Cultures. He is a founding member of the Association of Urban Photographers (AUP), a guest editor for the Imaginations Journal for Cross-Cultural Image Studies and a guest publisher with The Velvet Cell. Kyler Currently lives in Toronto, where he is a doctoral student in the joint Communication and Culture program at Ryerson and York University.

Following today, Kyler has initiated a week of Western Canadian photographers—surely a fruitful week ahead of us all. In defining Western Canada, Kyler states:

Defined here, Western Canada is an amalgamation of the prairie regions (with varying prairie climates) of Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and the Cordillera region of British Columbia—mountains and prairie grass juxtaposed. However mundane, landscapes are nonetheless monumental, exerting a place-specific vision upon its inhabitants. From a phenomenological perspective, one “unself-consciously and self-consciously accepts and recognizes the place as integral to his or her personal and communal identity and self-worth” (Seamon 17). That is to say, the landscape and place-attachment produces a particular way of seeing and understanding the land based on prolonged interaction. An Albertan ranch-hand once shared an anecdote with me that captures the contradictions in holding different perspectives of the land. A lumberjack and a farmer stand shoulder to shoulder facing East towards the Rocky Mountains. The lumberjack says, “Now isn’t this something to look at?” The farmer replies “But it’s blocking the view.” The Rocky Mountains act as a natural barrier between the boreal forest and the prairies, a formation to be breached by pickaxe and dynamite, and although passages between the two has been established, the differing geography poses more than a symbolic rift. Geography extends beyond a way of seeing and becomes a way of living. Distance has the ability to breed difference (cultural, economic, and social). As Author Brian Moore observes in The Luck of Ginger Coffey, geography is the enemy and the battle over it has yet to be won. Modifying Moore’s claim that geography is the enemy, we can interpret the enemy not simply as geography but as distance—nowhere else is this more observable than in studies of Canadian space (the Far North as well as the Canadian West). Viewed at a distance, the differences in geography and climate of the West become obscured and the specificities of the Canadian West become invisible—the mountains, plains and prairie fold into each other and come to represent a unified space. How Western Canada is defined is often debated.

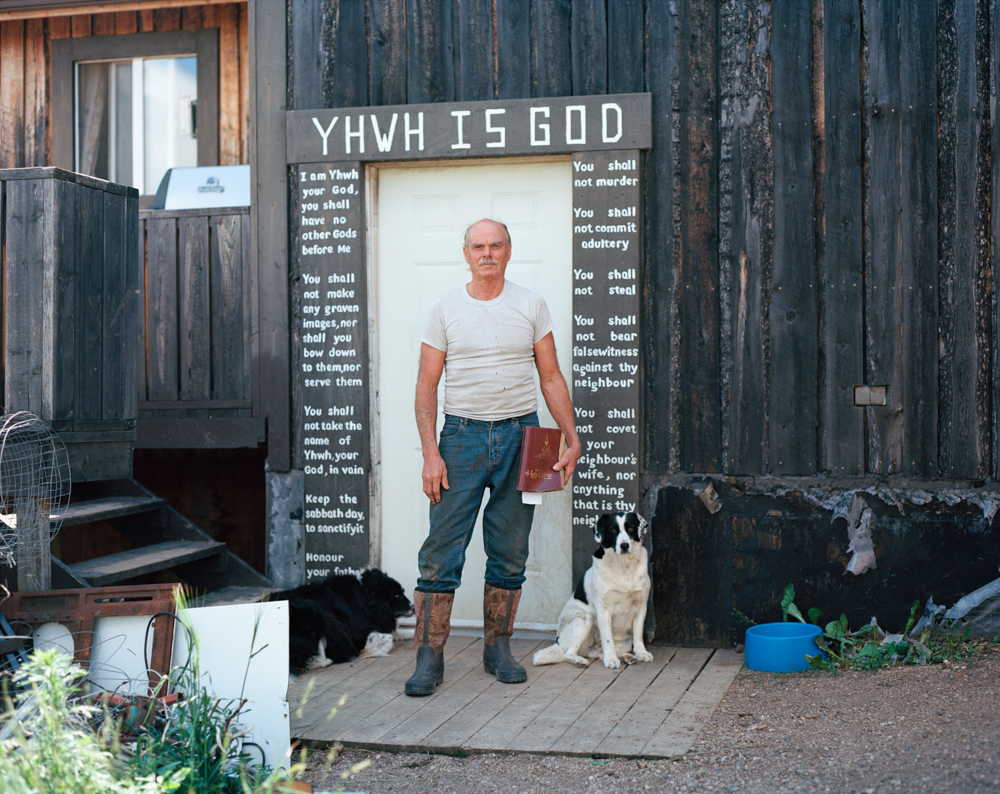

Soil made the farmer, the herd the rancher, and so what are we, or rather, who are we? Essential to identifying Western Canada involves forgetting the American Frontier. North America’s last great land rush took place in the Canadian West at the turn of the 20th Century. Often overshadowed (and sometimes visually conflated with its neighbour to the south), we forget to turn our gaze to the Canadian West. An area settled by a unique brand of hardened frontiersmen—cowboys, ranch-hands, miners, outlaws, and farmers—good ole boys chasing the advertised allure of a landscape made mystical by its inadequate representation, its mystery, its promise of the last ‘Promised Land’.

Gone are the early remnants of the Canadian West but its legacy still endures. Crown Ditch and the Prairie Castle is a long-term project that documents the spaces and people of the last great ‘proving out’. The project advocates for viewing this space as a beast upon itself, with a particular type of people, shaped by industry and landscape, who are a resilient breed created by generational lessons in fortitude and fortuned circumstance.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Kevin Cooley: In The Gardens of EatonJanuary 8th, 2026

-

William Karl Valentine: The Eaton FireJanuary 7th, 2026

-

Sean Stanley: Ashes of SummerJanuary 6th, 2026

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026

-

Andrew Lichtenstein: This Short Life: Photojournalism as Resistance and ConcernDecember 21st, 2025