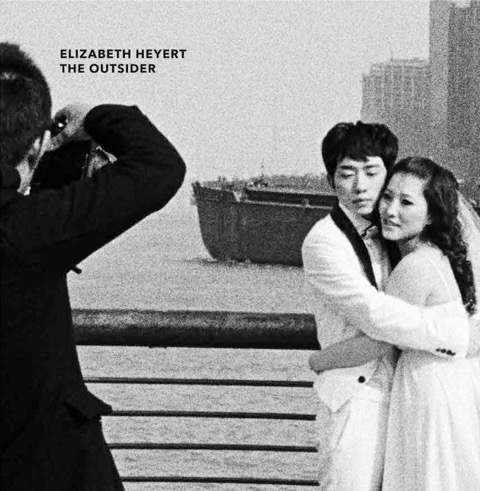

Elizabeth Heyert: The Outsider

“I call the project The Outsider because as a Westerner in the East, and a stranger in a foreign culture searching for authenticity, I allowed myself to be a spectator to the photographer/subject relationship.” — Elizabeth Heyert

There are a few aspects of life in Los Angeles that really bring out the Philadelphia in me, and almost all of them have to do with tourists. I’ve done my best to resist the instinctive eye-roll when I see a gaggle of hikers posing with a selfie stick at a crowded Runyon Canyon overlook. Or when someone obstructs sidewalk traffic to capture the perfect “candid” Instagram in front of a Venice Beach mural. Tension between exaggeration, invention, and reality are an assumed component of Los Angeles life. However, in a country like China, where visual history is sparse as a result of the Cultural Revolution, truth and performance become muddled by the pervasiveness of smartphones. Photographer Elizabeth Heyert seeks to explore these complexities of Chinese life her new book, The Outsider, published by Damiani.

Heyert’s experience photographing people documenting their environment is a departure from staged portraiture of the Other, which can often impose the cultural tinge of the photographer on the subject. Instead, Heyert is content as the observer, allowing her images to capture subjects as they desire to be captured. This two degrees of removal from her subjects raises many questions about how history and culture can influence perceptions of ourselves and our environment.

Elizabeth Heyert, formerly a world-renowned architectural photographer, established her reputation in the art world with her groundbreaking trilogy of experimental portraits, The Sleepers, The Travelers, and The Narcissists. Her photographs are in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and in numerous private collections. Her many books of and about photography include: The Travelers, the award-winning book from her series; The Sleepers; The Narcissists; Metropolitan Places, one of the classic anthologies of 20th-century interior design which she wrote and photographed; and The Glasshouse Years, a history of 19th-century portrait photography. Heyert lives and works in downtown Manhattan.

The Outsider

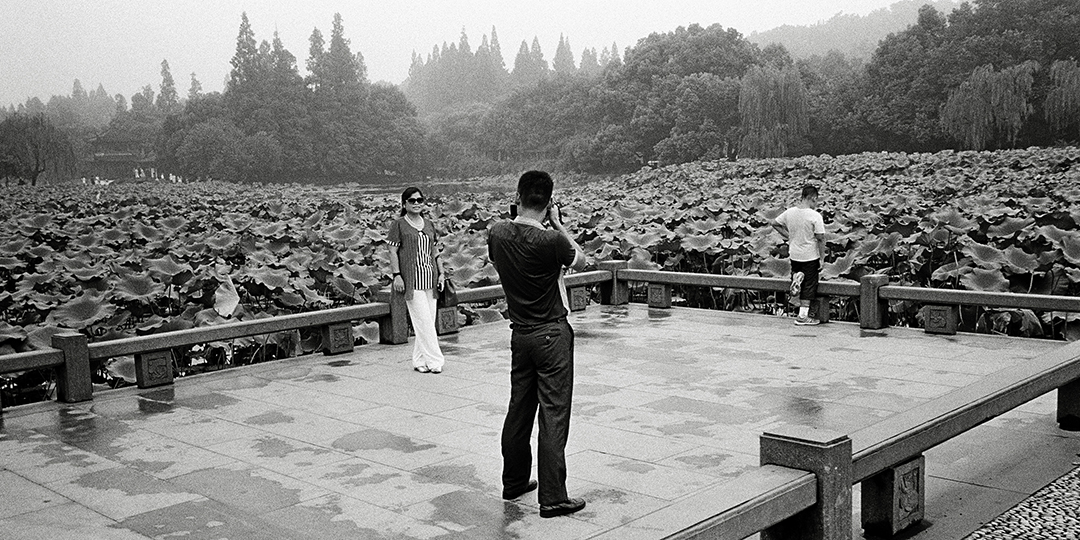

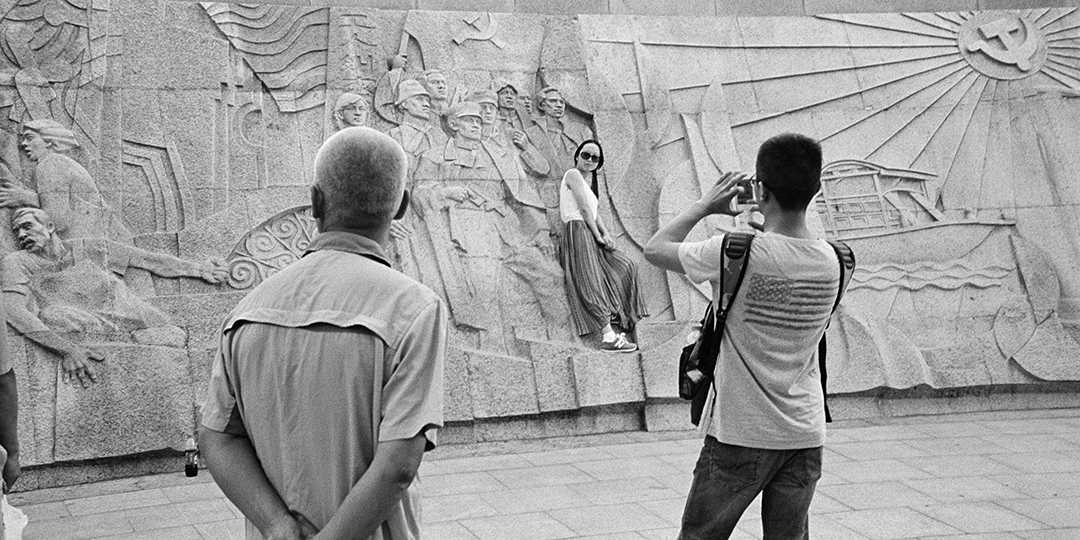

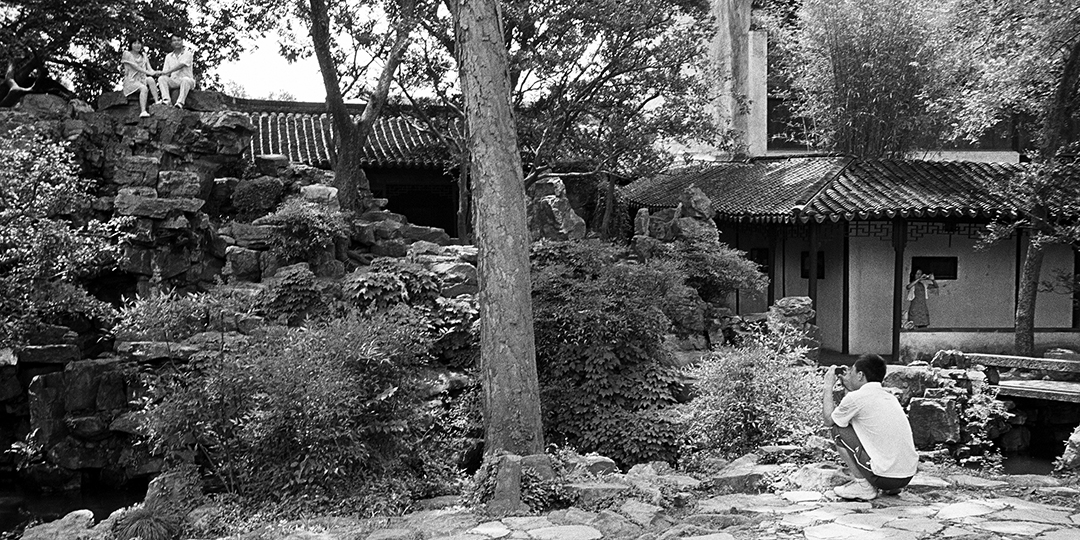

In 2014, I embarked on a project to photograph the Chinese taking photographs of each other. The rituals of Chinese amateur photographers fascinated me. They shoot incessantly, often with family members looking on and directing, and with an intimacy with their environment that borders on stagecraft. During the next two years, I traveled to Beijing, Shanghai, Suzhou and Hangzhou, often wading through enormous crowds to uncover and photograph private moments between people who were strangers to me. Unable to speak Chinese, I worked like a silent ghost, wandering around with a vintage Leica and Tri-X in a country where film is no longer even sold. Few Chinese possess family photographs from the past as so much was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, which may explain the intensity of the photography I saw wherever I traveled. I call the project THE OUTSIDER because as a Westerner in the East, and a stranger in a foreign culture searching for authenticity, I allowed myself to be a spectator to the photographer/subject relationship. These are portraits of the Chinese by the Chinese. By giving up my familiar role as portrait maker, I became instead an eyewitness to the birth of a new collective visual memory.

Yet, as an outsider I can’t be sure that what I witnessed made me any more aware of what is true. Did the young Chinese woman in Chanel sunglasses and designer clothes pose on the wall depicting the Workers Revolution because she admired the background, or was it an ironic political statement? Do the bride and groom, hugging in front of the surreal cityscape of Shanghai, cling to each other with intense love or desperate anxiety? Are the crowds of Chinese with cameras preserving memories of happy moments, or inventing happy moments to memorialize in photographs? Or are they trying to obliterate memory, to wash away the horror of the harsh years by creating an optimistic, fresh, modern personal history? I don’t know the answers. -Elizabeth Heyert

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Anastasia Tsayder: ARCADIAJanuary 28th, 2026

-

Ed Kashi: A Period in Time, 1977 – 2022January 25th, 2026

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Kevin Cooley: In The Gardens of EatonJanuary 8th, 2026

-

William Karl Valentine: The Eaton FireJanuary 7th, 2026