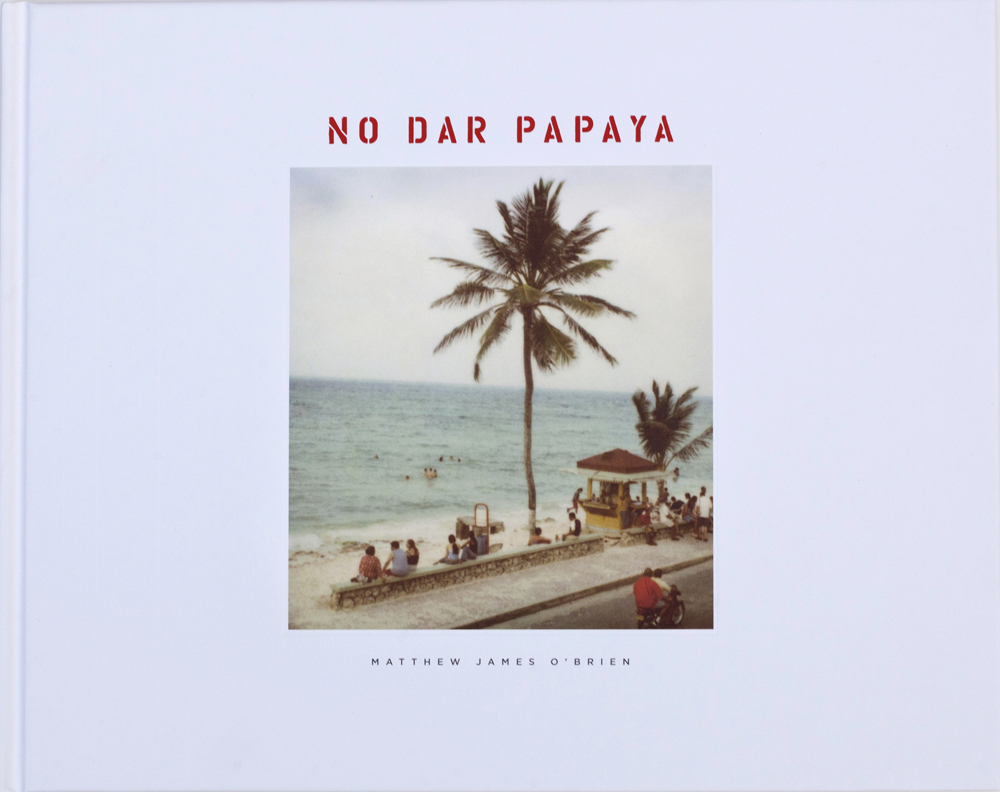

Matthew James O’Brien: No Dar Papaya Revisited

Sometime back, I featured Matthew James O’Brien’s project, Dar No Papaya and a Kickstarter campaign he had created to raise funds for a monograph under the same title. Unfortunately the Kickstarter did not reach its goal, but he was still able to make the book a reality. Today, we not only feature work from the project and his book, but also an interview that explores his road to publishing and how he moved forward after a disappointment.

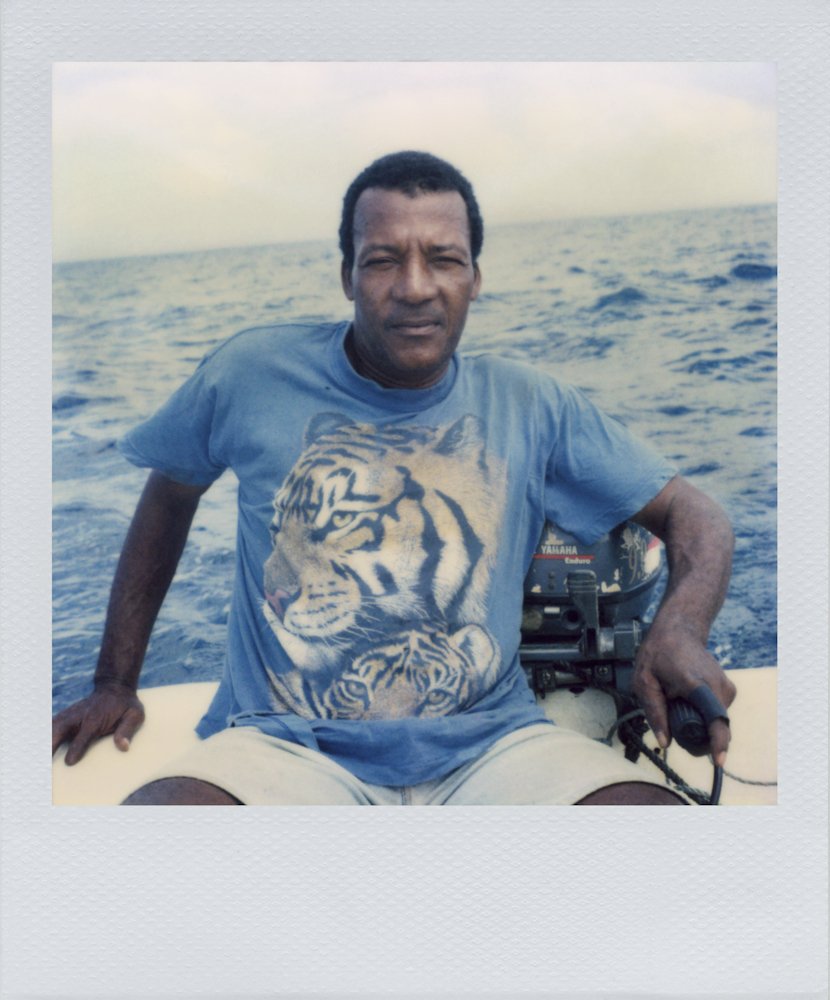

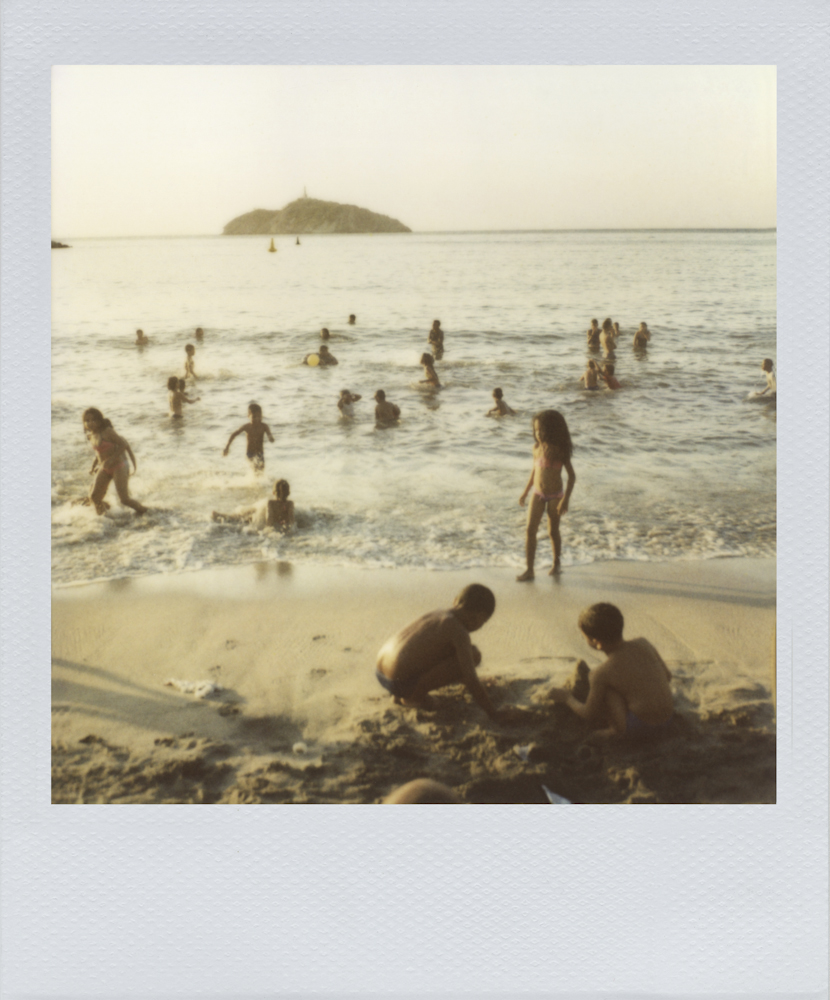

For the last ten years, Matthew has been focused on creating photographs with a Polaroid camera and film to create “alternative to the stories and imagery in the media of conflict, violence, drug trafficking, and assorted horrors (called pornomiseria in Colombia).” No Dar Papaya (a Colombian expression meaning don’t present an easy target), published by Placer Press, focuses on the country’s beauty and humanity. The book can be purchased here.

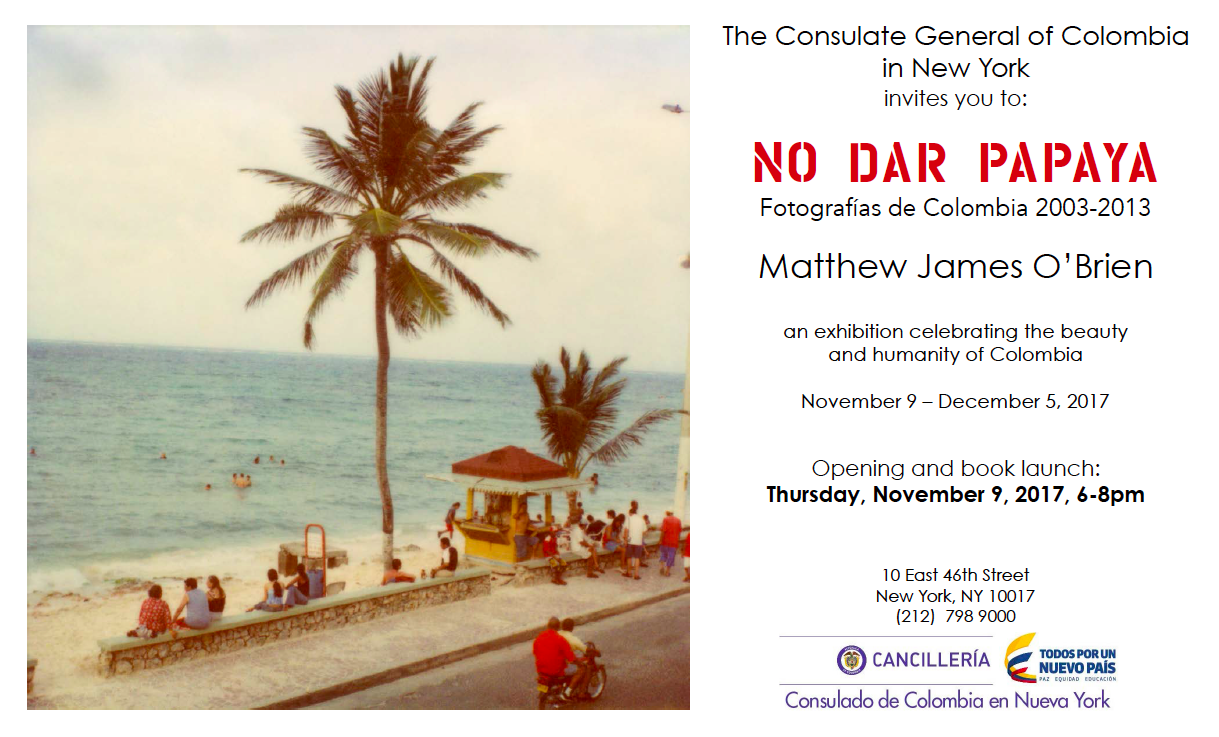

Matthew will have a book launch tonight at the Consulate of Colombia in New York from 6-8pm.

I was born and raised and live in California. I studied zoology at the University of California at Berkeley. My understanding of animals, evolution, and the natural world informs my views of humanity and my photography. A common thread in all my work is it that I am drawn to beauty, in one form or another, no matter the circumstances. I like to create work that is affirming and has the potential to lift spirits. In addition to making photographs, I also teach photography, in English and Spanish, and make films.

Among the awards I have received are a Fulbright Fellowship, a Mother Jones International Fund for Documentary Photography Award, and a Community Heritage Grant from the California Council for the Humanities. My work has been exhibited and collected by various institutions including the Library of Congress, the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, the California Museum of Photography, the Fries Museum (Netherlands) and el Museo de Arte Moderno de Cartagena, and has appeared in various publications including The Washington Post, Mother Jones, Slate, and Camera Arts. – Matthew O’Brien

No Dar Papaya

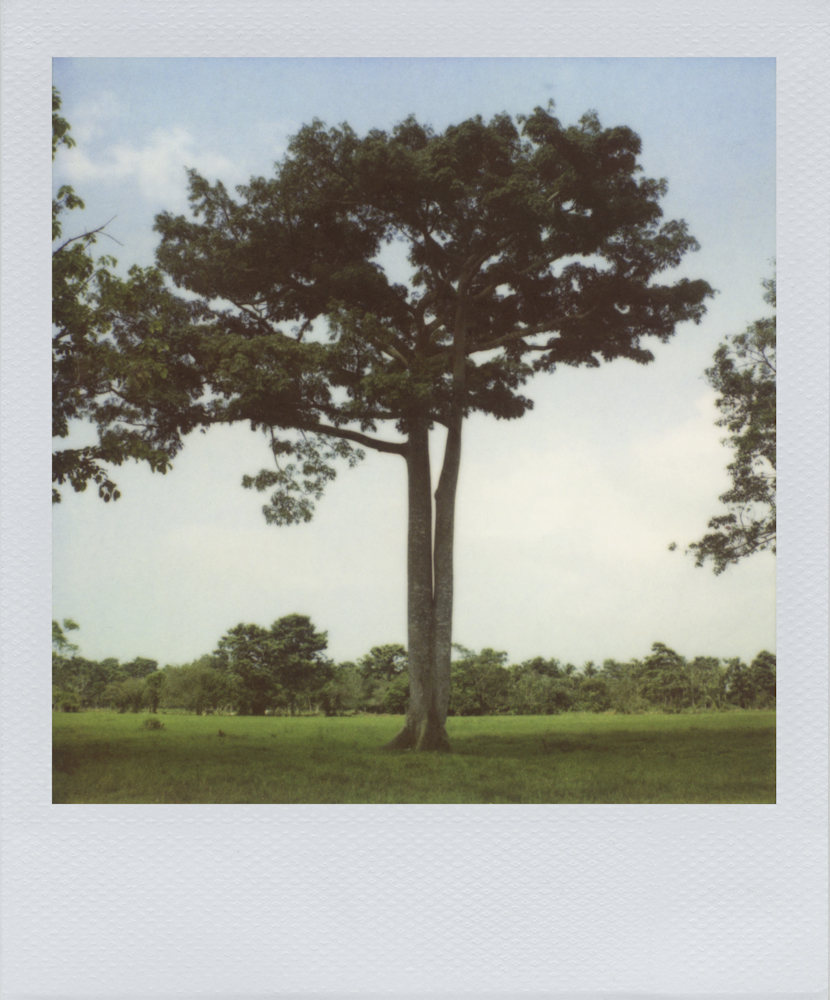

No Dar Papaya is a photographic exploration of Colombia created with a Polaroid camera and film over eleven years.

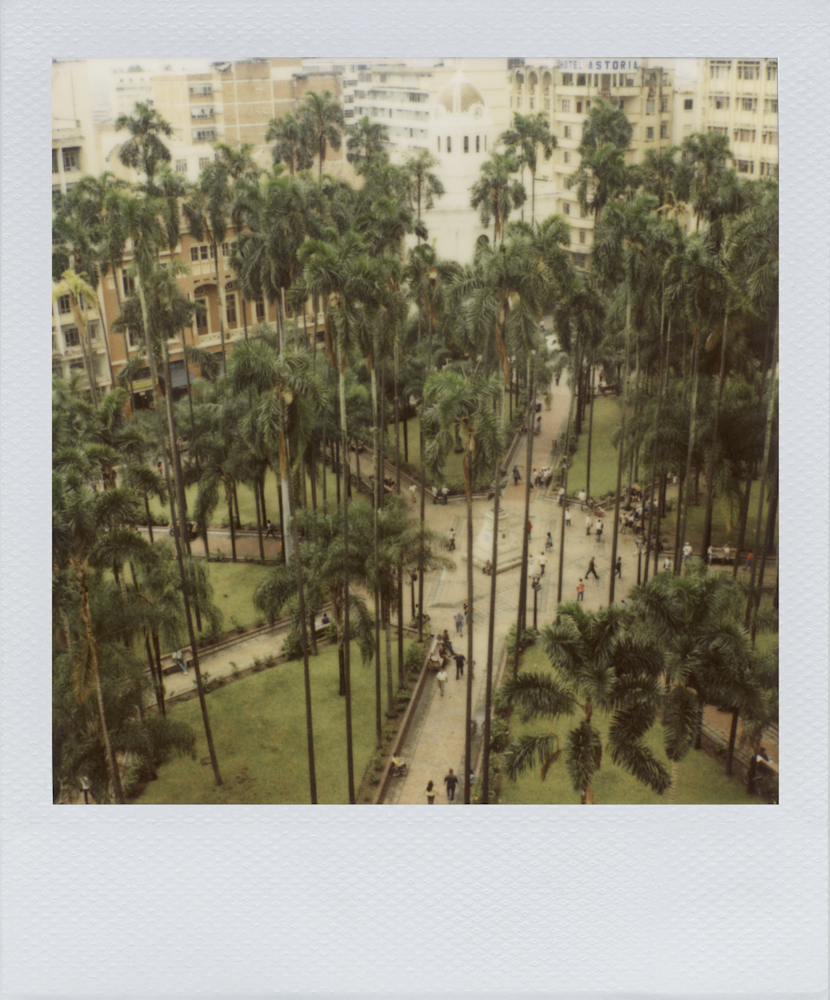

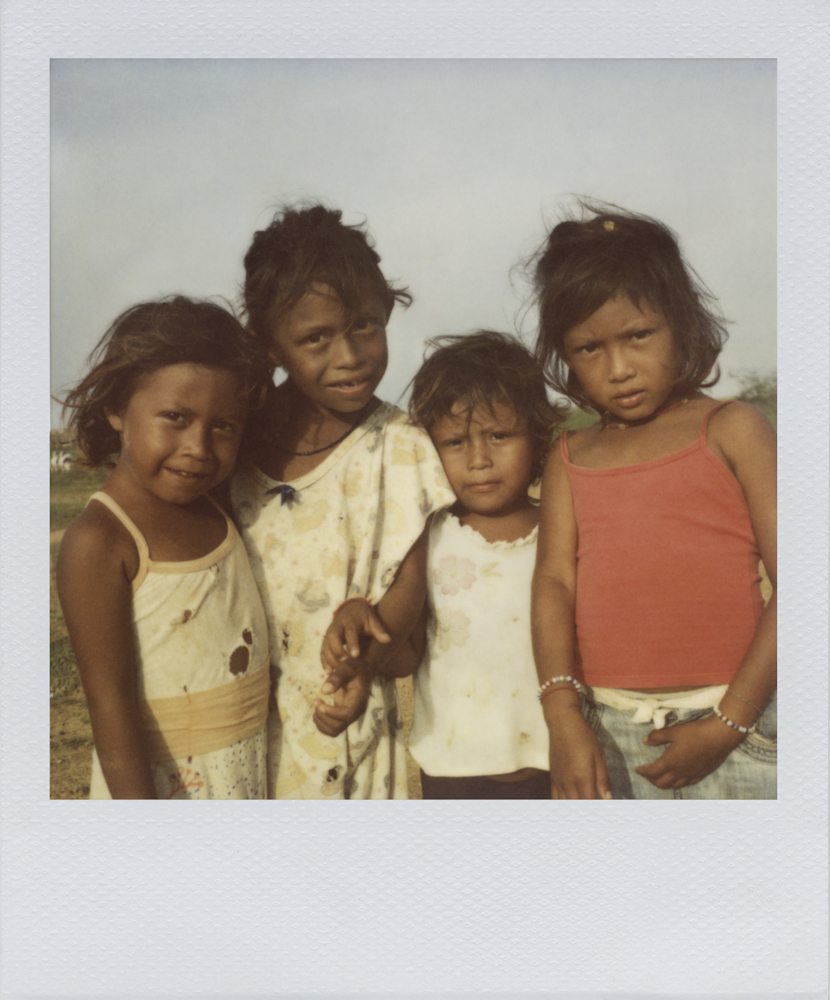

The series offers an alternative vision of Colombia– alternative to the images of war, violence, and misery that dominate imagery from Colombia in the media. That kind of imagery (so common in Colombia there’s a name for it, pornomiseria) is not what interests Matthew O’Brien. He is much more interested in representing his experience of Colombia, where he finds lots of beauty, warmth, and humanity.

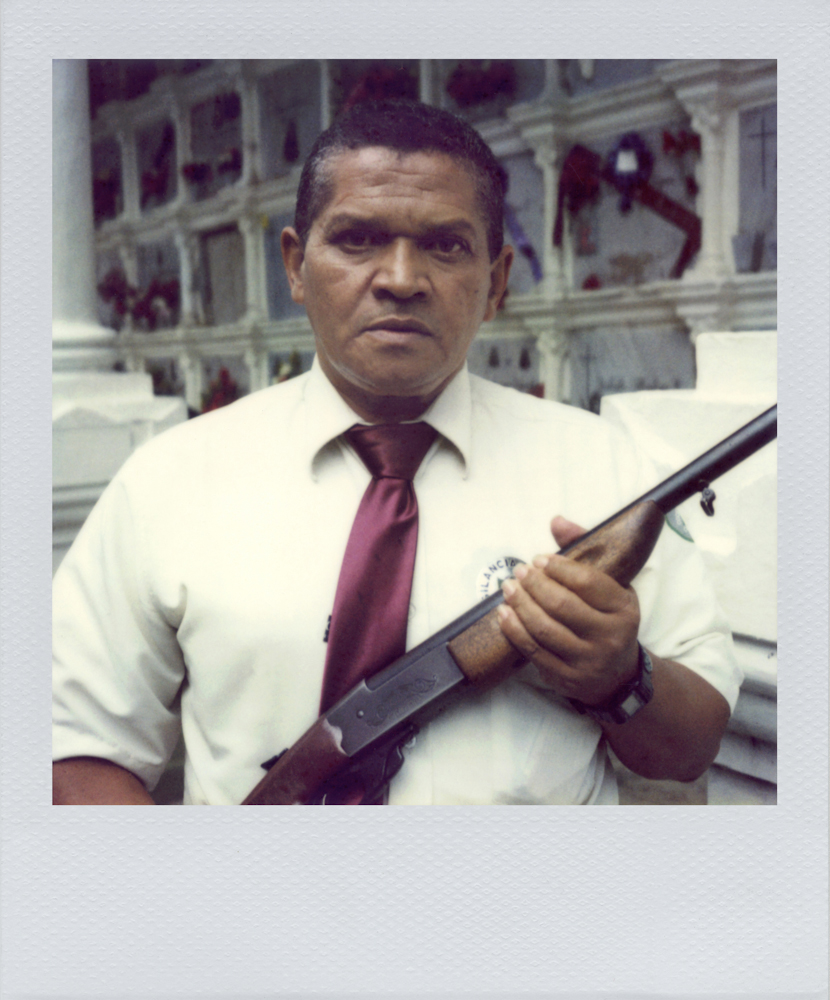

The softness and the distinctive color pallet of Polaroid gives an impressionistic quality that leaves more room for interpretation, reflecting the artist’s experience of Colombia: a foreigner in a new culture often doesn’t fully understand what he is observing– much is open to interpretation. The series doesn’t pretend to give an overview of the country, but rather a personal collection of moments, individuals, and places that together speak of realities and possibilities in Colombia.

The title, No Dar Papaya, is a common expression unique to Colombia which means show no vulnerabilities and don’t present an easy target. It speaks to the reality of life in Colombia, now in its 53rd year of war. Tens of thousands have been killed and hundreds of thousands displaced from their homes. Unspeakable cruelties continue to happen. It has a rigid class structure and the greatest disparity between haves and have-nots in Latin America. There’s lots of crime in the cities. Amid this, people live their lives with lots of creativity, joy, humanity, and beauty, and that is what interests the artist.

The last time I featured your project, you had a created a Kickstarter campaign to launch a book. Can you tell us about that experience?

I learned a lot, most obviously, that I was not the right person to do a Kickstarter campaign. You’re best off with an active social media presence and an extensive network in the photography world, neither of which I had/have. There are lots of photographers making interesting, worthy work. Only a fraction of that ends up being seen by the public because there is so much competition for attention for a given project. So, work that becomes known and seen has a lot to do with promotional efforts and not necessarily the quality and nature of the work. It’s been that way for a long time. With social media and Kickstarter especially, it’s that on steroids. So, if you are well-connected with publications, organizations, and institutions, you are more likely to have an infrastructure in place to promote your project. For example, some photographers use the resources of the universities where they teach to promote themselves and their personal projects.

I’m an independent artist. I’ve always created work because I’ve been moved to for personal reasons, not because of a calculation of what might be marketable. And let’s face it, Colombia, and Latin America, aren’t the most popular of topics for an American audience. I overestimated its appeal and my ability to reach people with the project. I’ve always been much more interested in creating work than in promoting myself, and when I was doing the Kickstarter, the consequences of that were made abundantly clear.

What was the hardest part of the Kickstarter and what advice can you pass on to people considering launching one?

It was very consuming– time, effort, energy. A lot of people recommend that for a Kickstarter campaign, whether it be photography-related or not, it’s best undertaken by more than one person, and I would agree. It’s also recommended to cultivate your potential supporters way in advance—like a PR campaign before you launch your campaign. That gives you a hint of the amount of effort required. They say there is Kickstarter fatigue. When the platform was novel, people were more likely to support a project. Now people are tired of Kickstarter projects. The vast majority don’t reach their goal. So my advice to anyone considering launching one is to evaluate the appeal of your project and your ability to get it to the right audiences, which largely depends on relationships. Evaluate whether there might be another way of accomplishing your goal if you’re not a person who likes to self-promote and not so fond of “the ask.” Are you prepared to devote the time? You could be doing other things.

I’m sure that not reaching your goal must have been defeating. How did you get re-energized and motivated to move forward?

Yes, it was a bummer. Well, you learn from the experience and figure out a different way. I was motivated because I really believe in the work, and I wanted to share it with an American audience. The failure of the Kickstarter campaign was a reflection of my shortcomings as a promoter and schmoozer, not of the work itself. It’s a strange “business” this photography world in which people often spend more money on their work than they make from it and spend tons of money on “exposure” opportunities/schemes that often don’t lead to much. I think it’s helpful to recognize the absurdities and have a sense of humor about it. And you gotta work hard, be persistent, and knock on lots of doors because many will not open.

It’s exciting that the project and book are launching in New York…tell us how that came about?

I’m from San Francisco, so I approached the Colombian Consulate in SF about having an exhibition and launching the book in the U.S. there. Fortunately, there was a new consul who appreciates arts and culture, and they were very interested in presenting the work because it offers a different vision of Colombia than the imagery of conflict, narco violence, and problems that is so common in the media. That exhibition became the debut of the work in the U.S. (There had been a series of exhibitions in Colombia where the book was first launched.) It was a positive experience for the people at the consulate in San Francisco, and they asked how could they help. The invitation to exhibit at the consulate in New York came about as a result of that. I’m honored to have been invited to exhibit in New York because they only exhibit the work of Colombian artists there and have made an exception for me.

Why Polaroids?

I love the softness and unusual color pallet of Polaroid. I have done lots of work in the documentary tradition. Two examples are Back to the Ranch, an exploration of ranching in the East Bay, across from SF, and its demise due to urbanization and Looking for Hope, a study of the public school experience and growing up in inner city Oakland. I found that I would create a huge number of images, more than I could use (good ones), and the projects would become unwieldy. Also, I felt that I had figured out how to do good documentary photography and at that point it had just become a question of whether I wanted to put in the time and labor. I was looking for new challenges and a different way to work and to express my ideas.

Working with Polaroid allowed me to conceive of a different sort of project. Instead of exploring one topic or community intensely, resulting in tons of images, I visualized a more extensive project made up of a lot fewer images. The impressionistic and abstract nature of the images allowed me to think that way. The images are more open to interpretation, I think, and I like that. And it worked for my personality. I didn’t have to deal with a tripod and hi tech equipment. You’re in diverse environments, from rainforests to city streets, and sometimes security is an issue, so not having to deal with lots of gear was key. And it wasn’t about filters and manipulating images at a computer–it’s pure photography that relies on the photographer’s vision.

There are lots of limitations and differences with the camera—one lens, shallow depth of field, rudimentary exposure controls (a plastic wheel you turn that’s white on one side and black on the other), slow, hard to compose, square format—that made it so I had to learn a different way of shooting. And because the film was expensive and later scarce (manufacture of Polaroid 600 stopped in 2008), I had to be very selective and more deliberate with what I shot.

There’s lots of great Polaroid work—portraits, still-lifes, nudes, landscapes— but people who know about these things tell me there’s never been a project of this scope created with Polaroid film and that it’s a unique photographic record of Latin America. I guess this work is informed by my documentary sensibilities, and that’s what makes it unique.

What draws you to Colombia?

I have friends from Colombia in the Bay Area and that’s what got me curious. I knew there was more to Colombia than the representations in the media would have one believe, and so I wanted to check it out for myself. I first went in 2003 to shoot a project that looked at Colombia through the prism of beauty contests. (I shot the project with 35mm film, but I brought my Polaroid and made a few pictures, some of which are in the book.) That went well, I had a wonderful time, and I was invited back the following year to exhibit that work, Royal Colombia, and to teach at a few universities.

I had lots of positive experiences. People were hospitable and warm, and it was exciting to be working in and learning a new culture. I have family in Italy and Ireland, so I have ties to those cultures. But in Colombia, I was figuring everything out on my own, and Colombia is a very interesting place. When I first went, people in the U.S. would freak out that I was going to Colombia because it was and was perceived to be more dangerous than it is now. There were very few foreigners there. So, it was fun being a novelty. It has changed considerably, and now there’s lots of tourism and backpackers.

Later I had more invitations, and eventually a Fulbright Fellowship. One opportunity led to another, and I kept discovering more interesting things about the country and kept being enthusiastic about the project. It’s a very diverse country geographically and culturally, and I like being in different cultures and learning about humanity. In the book the images are more or less in chronological order, the narrative being that the reader accompanies the author on that journey of discovery.

What have you learned about the country over the years?

I’ve learned that the human experience is so different across the globe. It’s a very different society than American society. Unlike the British, who had this idea of we will make new communities for ourselves in the New World, the Spanish had more the concept of we will subjugate the people of those lands and rule over them. And you see that legacy in Colombia in obvious ways (rigid social classes, huge divide between haves and have-nots, of which the war, which has gone on for over 50 years and whose effect on society cannot be understated, is a result), but also in more subtle ways like a lack of respect for pedestrians, lots of crime, and attitudes about government and work.

There’s lots of unpleasant stuff that happens in Colombia that I learned about: people being violently displaced from their lands because wealthy interests covet them, the Wayuu, the largest indigenous group in Colombia, who live in La Guajira, in the north, suffering from malnutrition and starvation because of government policies and the water in the arid region being taken over by a transnational coal company, and the list goes on. A new experience for me was getting attacked by a guy with a knife.

But I also experienced lots of beauty. I came to really appreciate the creativity of Colombians and how it is valued and expressed in so many ways. I came to appreciate how people cope and adapt to different conditions. Amidst harsh circumstances, there can be lots of beauty, and joy and creativity. And that’s what I am drawn to and what my work is about. I want to create work that is affirming, that is beautiful. Life already has enough difficulties– I think beauty can make life better, so I try to do my part. In Colombia lots of people thanked me for creating the work, for, in a country famous for problems, recognizing beauty and good things that they themselves often don’t recognize. It was very nice to hear that.

What’s next?

Last year I spent several months in Thailand and Burma and did some photography and made a film. I’m interested in continuing a project that looks at the Salween River, which is only one of two rivers that flows from the Tibetan Plateau to the sea that is not dammed. Of course there are plans to do so in several places. It goes through Tibet, China, Burma, and Thailand, passing through many diverse cultures and landscapes. No community along the river wants dams. These decisions which would destroy villages and hurt thousands of people are being driven by governments and greedy interests in far-off cities.

I made a film called For Our People (https://vimeo.com/172561464) for an NGO that provides educational opportunities to migrants from Burma in Thailand (who don’t have lots of opportunities or rights). I enjoyed the experience immensely and the film helped the NGO raise a lot of support, which was very gratifying. I am very interested in making more films, but I have a lot to learn.

For Our People from Matt O’Brien on Vimeo.

And finally, describe your perfect day.

A perfect day for me would include good experiences with people, especially loved ones, exercise, good food, experiencing nature, and doing creative work that I’m enthusiastic about.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Time Travelers: Photographs from the Gayle Greenhill Collection at MOMADecember 28th, 2025

-

Marcia Molnar: The Silence of WinterDecember 24th, 2025

-

Paccarik Orue: El MuquiDecember 9th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025

-

Interview with Maja Daniels: Gertrud, Natural Phenomena, and Alternative TimelinesNovember 16th, 2025