Wayne Martin Belger: Us & Them

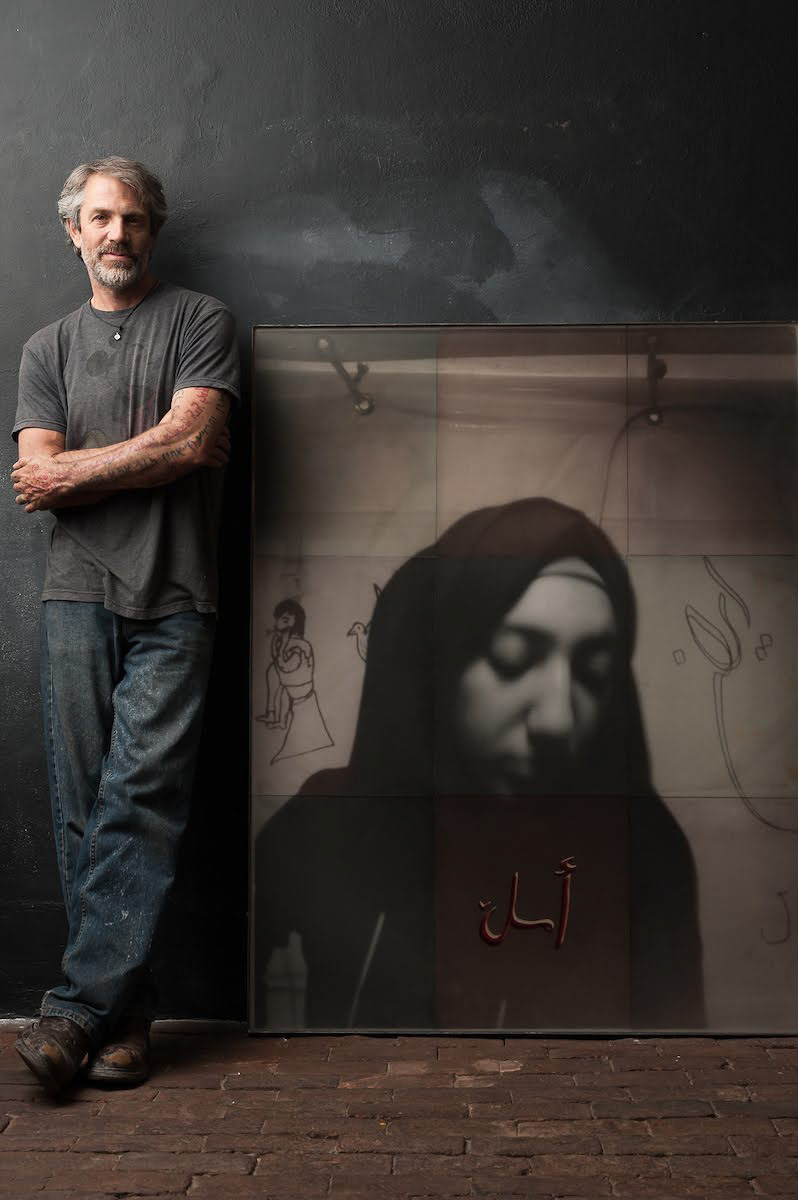

© Jade Beall, Wayne Martin Belger with finished print “Us & Them, Moria #2.” Photo of a refugee woman in the Moria refugee camp in Lesbos, Greece.

I first discovered the work of Wayne Martin Belger about six years ago doing a Google search for DIY, homemade cameras for a personal project I was working on. I stumbled upon images of several of his painstakingly crafted pinhole cameras. I remember rushing into the next room with my iPad to show my wife because I couldn’t contain my excitement. I felt the same excitement several years later sitting in a conference room at the Medium Festival of Photography in San Diego when I suddenly realized that the speaker I was waiting for was that same guy who made those amazing cameras and I was going to be able to see them in person.

But to characterize Wayne Martin Belger simply as a photographer who makes his own cameras would ignore the depth and complexity of his work. Wayne is a photography-based installation artist whose exhibitions consist of both the hand-made camera and photographs produced by the camera. Central to his work and process is his deep personal connection to his area of interest and subjects and the cameras he builds are a key part of that connection.

“I was taught by an old-school German machinist that your tooling and all the tools that you make are an extension of you and your body. So I make the cameras that are a complete extension of the art and myself.”

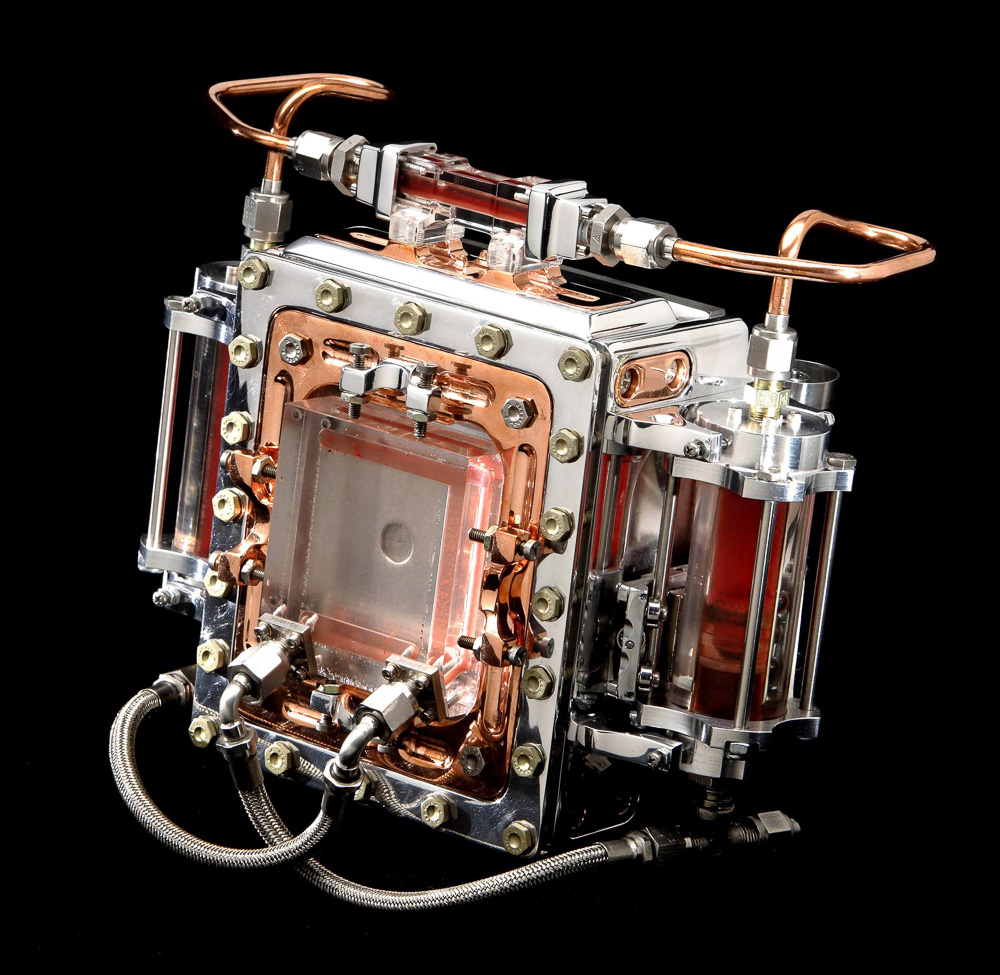

Each camera is created for a specific body of work, containing artifacts specific to that area of study. He created a camera that circulates a sample of HIV-positive blood as its red filter for photographing portraits of people living with HIV. He created a camera that incorporates an infant’s heart in formaldehyde to explore the relationship between mothers and their soon-to-be-born children.

“For me the camera is my bridge between me and the subject that I want to learn about and what I want to investigate, so I make it the intention or that focal point for me to go forward, to bridge a gap, … It’s my bridge to that subject.”

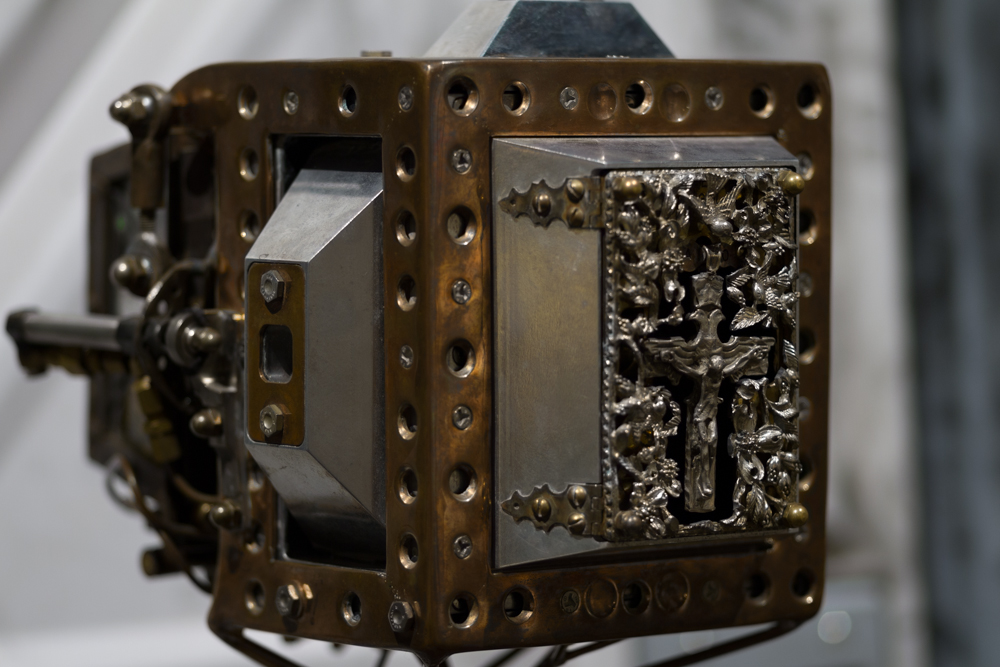

His most recent body of work, “Us & Them,” focuses on the artificial separation, division, and de-humanization that governments and the powerful use to dominate people and preserve their power. For this project he spent months creating a camera incorporating powerful symbols relating to that dehumanization, including a crucifix once owned by Eva Braun (Hitler’s girlfriend/wife), an armband a Jewish person was forced to wear in WWII, prayer beads from a current-day Syrian refugee, and human remains from the Vietnam war. The unique talismans included in his cameras are often given to him by people who hear about his work.

“…They are from a Vietnam Vet… …he was required to keep a body part from every person he killed. His daughter knew my work… She told her dad about it because she knew her dad had this box and he was tortured by it. When he was in Vietnam he was taught that the Viet Kong were less than human and it’s OK to kill them and take a trophy – it was required. He didn’t want to throw them away and he didn’t want to bury them. He liked the idea that these items could bring awareness that there is no “us” and “them” – that the Viet Kong weren’t dogs. He has such resentment that he was programmed to believe this that he donated the parts to me.”

Wayne’s use of these items is rooted in his religious heritage and childhood experience. Wayne has been collecting and assembling powerful spiritual artifacts since he was a child.

“I was brought up as a good little Irish Catholic boy, but we have some interesting spiritual aspects in my family – one was Santeria and Voodoo. I was brought up with alters and shrines being a focal point for your intentions. A lot of people in my family were believers, so if you wanted to go in some direction, you’d set up an alter that was part of you and your spiritual practice to try to bring that intention forward. So, growing up around that, I started making alters and shrines when I was 5 years-old.”

Wayne comes from a long line of engineers and is a master machinist and craftsman. His cameras are exquisitely crafted pieces of functional art and objects of beauty in their own right. They are often decorated with precious and semi-precious stones. And the precision and beauty of the moving parts is astounding.

“For the camera itself, I start creating it in my head, so I start incorporating the pieces that have been given to me with the functionality of the camera and then start putting it all together in my head. … I don’t write anything down, but I will make every piece, every screw, every cut, every angle of the camera in my head. When I feel like the camera is finished, then I will start machining out the parts.”

But the cameras are just the beginning of the project — a means of connecting with the area of study and his portrait subjects. For the Us & Them project, Wayne travelled with the camera and took portraits of people in oppressed and persecuted communities. He and the camera have been to Syrian refugee camps in Lesbos, Greece, the Palestinian territories, Standing Rock North Dakota, and the mountains of Chiapas Mexico to photograph the Zapatista National Liberation Army. The camera itself often helps him break down barriers with his subjects. But it is his own dedication to understanding and immersing himself in the circumstances of his subjects that has produced a series of powerful and moving portraits.

“People see an art piece and they want to be connected to it, whereas they see a camera and they want to hide. It becomes a bridge. It’s been a beautiful process for me because I love people.”

© Jade Beall, Wayne Martin Belger explains the “Us & Them” project in a Zapatista compound in Chiapas, Mexico.

“Every place I’ve been I feel like I get such gifts from the people that I want to connect with them and photograph them. It doesn’t even seem like the photograph is my priority, but I want to collaborate with them to make a photograph. The main part was getting to be in a Palestinian’s home or freezing my ass off in a teepee at Standing Rock in North Dakota.”

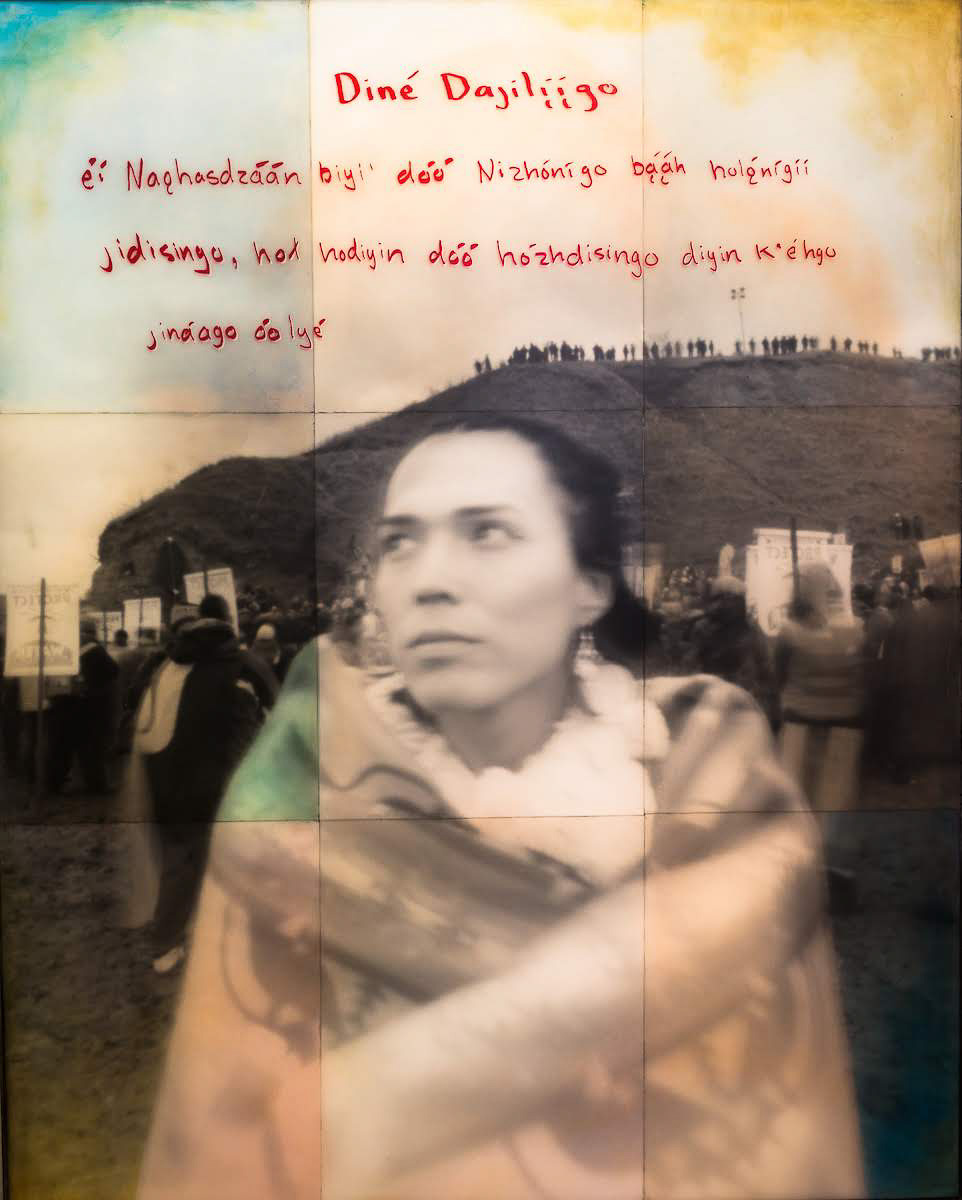

© Ryan Vizzions, “Us & Them” photo shoot of a Navajo woman during a NoDAPL confrontation in Standing Rock, North Dakota.

© Jade Beall, “Us & Them” photo shoot of a Zapatista commander and his platoon in Zapatista military compound in Chiapas, Mexico.

© Sandi Sandelier Blankenship, “Us & Them” photo shoot of an Afghani refugee and her baby in the Moria Refugee Camp in Lesbos, Greece.

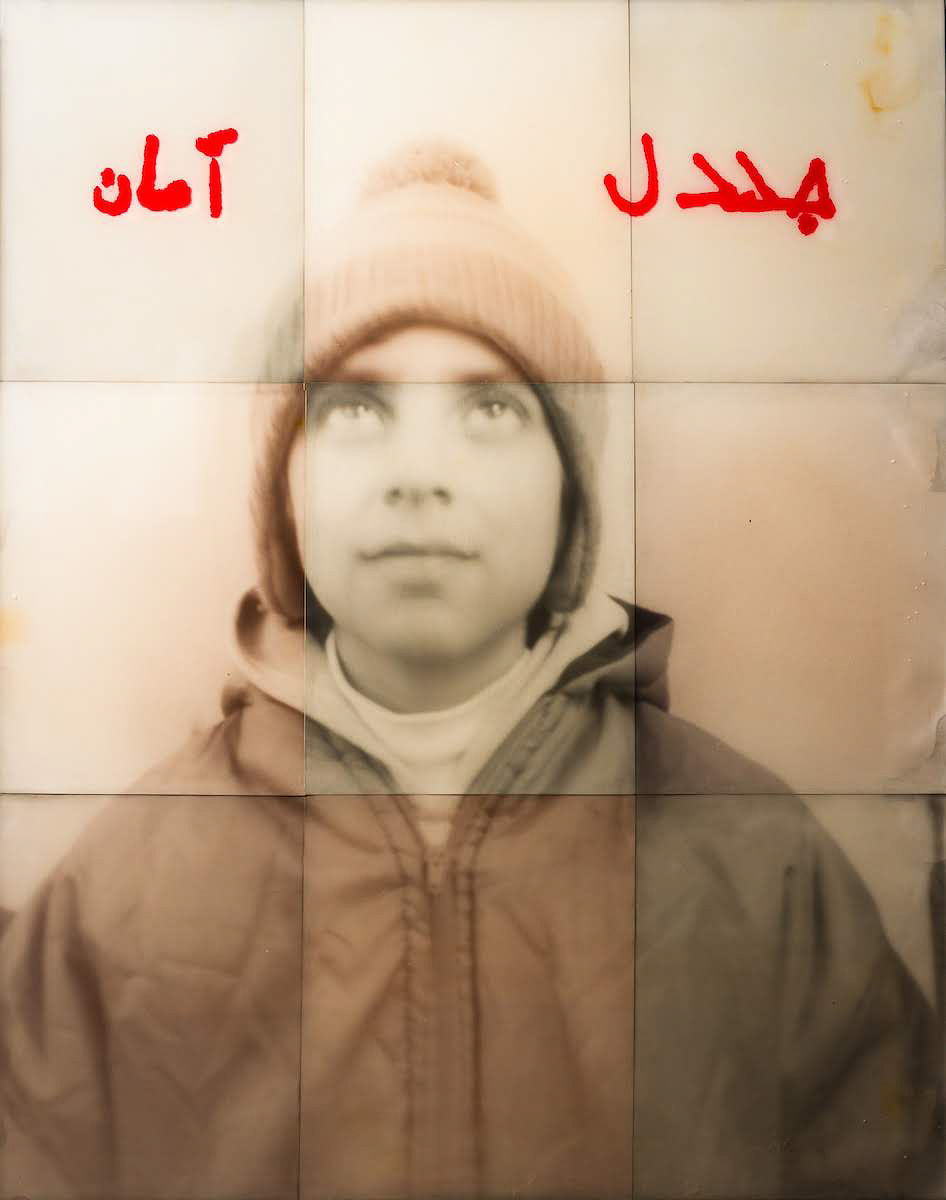

Wayne likes to leave something with each of his subjects. He has outfitted his camera to accept 4” x 5” Polaroid Film as well as 4” x 5” negative film.

“I like to give the person I’m working with a Polaroid of the shoot. Many of the people I’ve photographed have no access to the internet and would probably never get to see the photo we made together. And for some (like most of the refugees and immigrants I’ve photographed) it’s the only photograph of themselves they own. Giving of the photos is one of my favorite things to do.”

© Wayne Martin Belger, After “Us & Them” photo shoot in the Syrian refugee camp, Kara Tepe in Lesbos, Greece. The young Syrian boy had just been photographed by the “Us & Them” camera. He’s holding a 4″ x 5″ Polaroid given to him by Wayne.

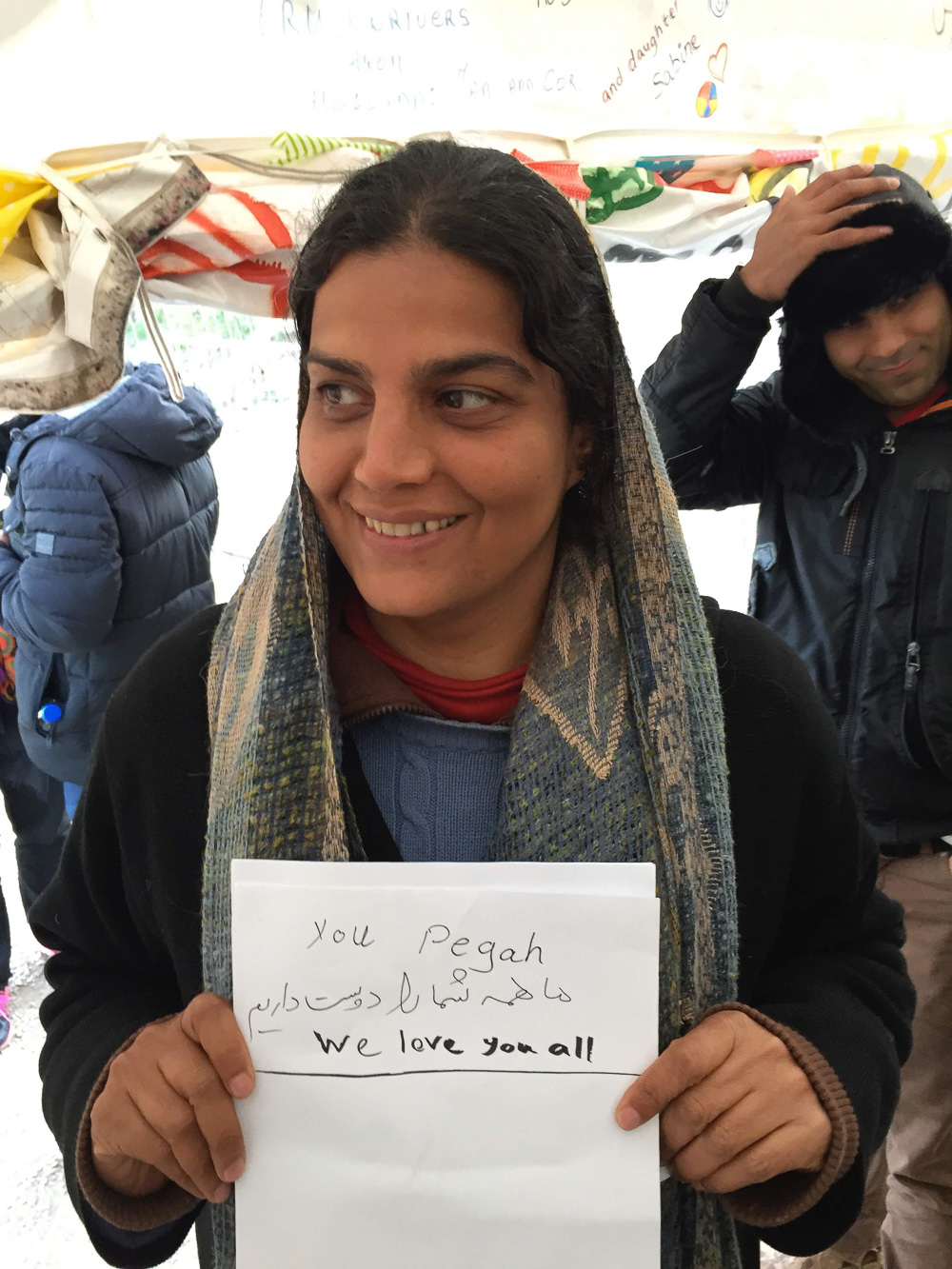

An important part of the Us & Them project is to give a voice and identity to individuals too often identified as “them.” To this end, Wayne asks each of his subjects to write “Words from the Heart” — a message in their own hand. That message is then incorporated into the final print.

“…it’s the people who have been dominated or abused that want to be part of it. It’s getting the word out. People want to be part of everybody. Nobody wants to be lesser. People who have been abused and labeled want to get the word out. People who are doing the abusing want to hide.”

@ Wayne Martin Belger, Afghani woman holding up her “Words from the Heart” after “Us & Them” photo shoot in the Moria refugee camp in Lesbos, Greece.

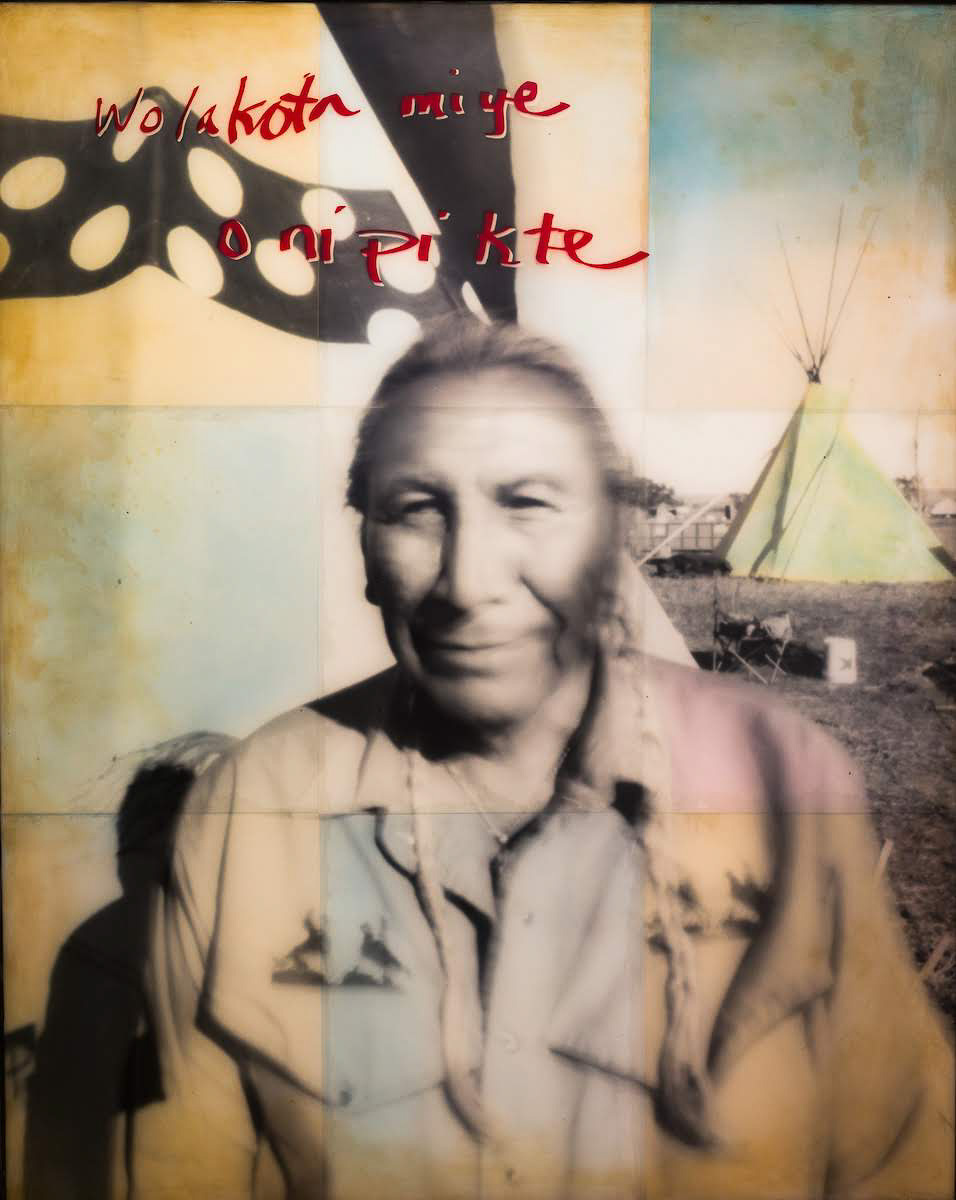

© Wayne Martin Belger, “Us & Them, Standing Rock #2,” 48″ x 60″ print from 9 sheets of 16″ x 20″ silver gelatin paper, toned with cochineal, prickly pear tea, and Zapatista coffee. 1 of 1, 2017

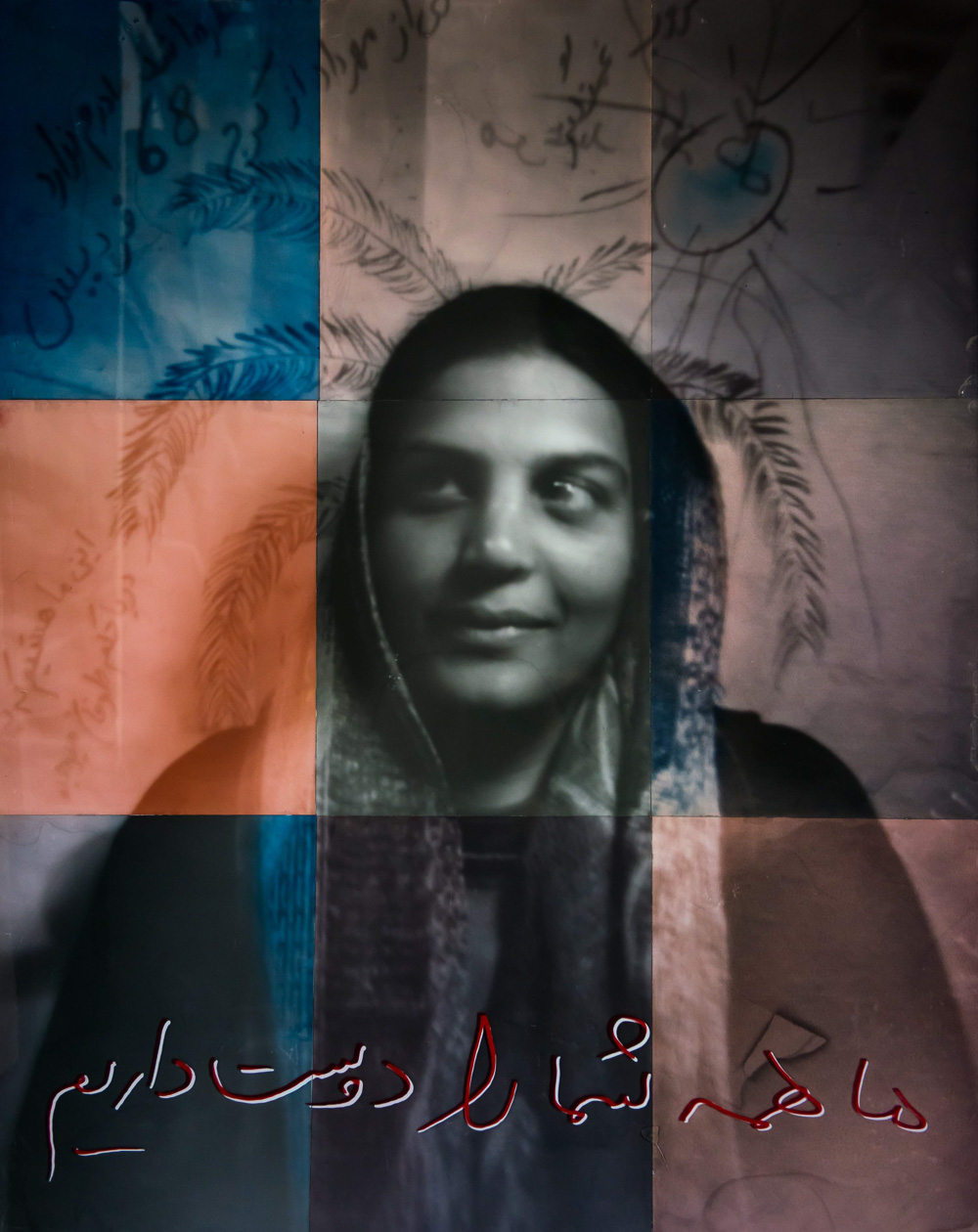

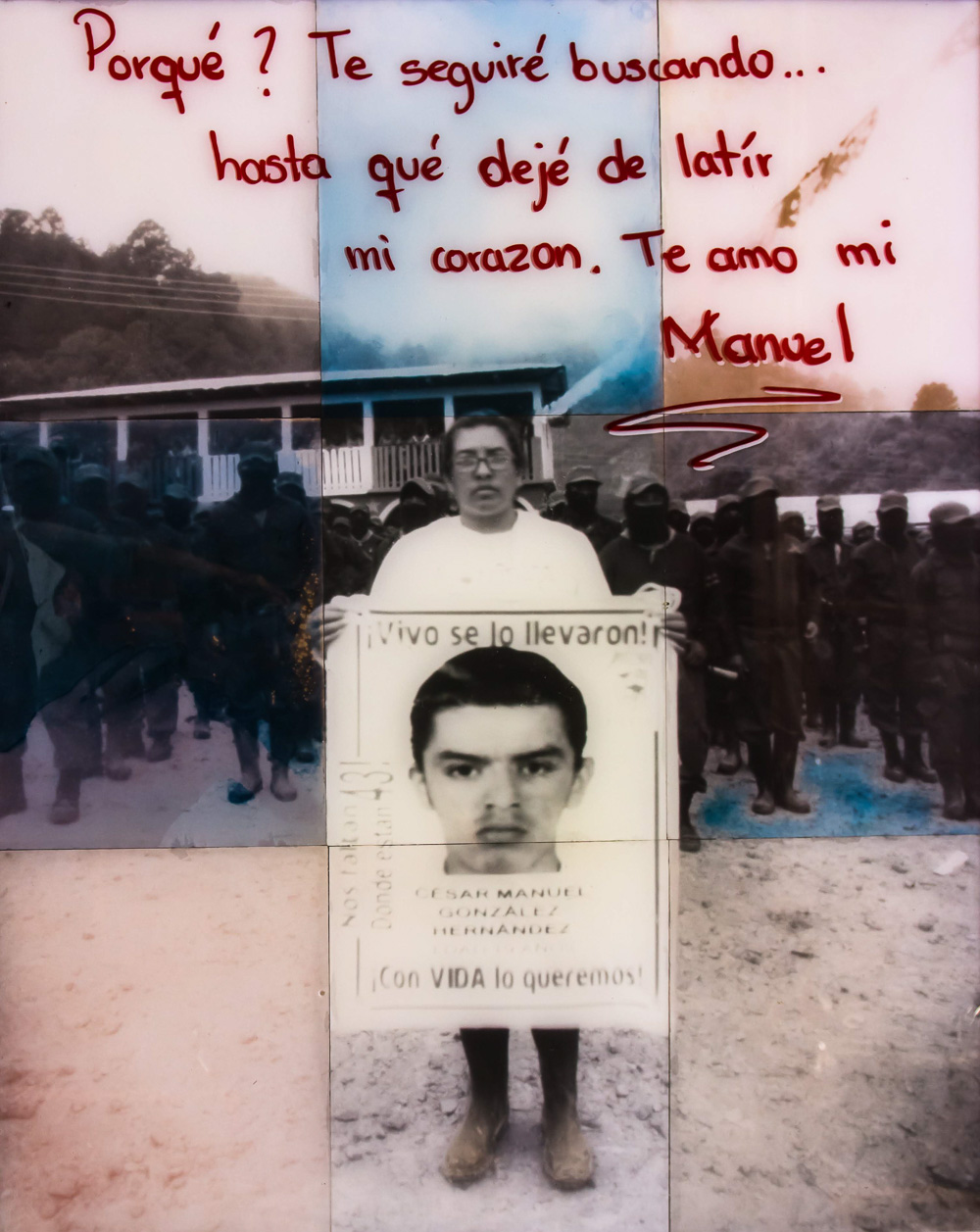

Wayne’s time-consuming printing process is a further example of his skill and dedication to craftsmanship. For the Us & Them project, he prints the portraits by projecting the negative onto grid of 16” x 20” photo paper taped to a sheet of foam-core and standing on an easel. Each sheet of paper is then removed and developed and toned separately with different processes so each sheet has a slightly different look.

“I couldn’t afford big sheets of photographic paper, but I had smaller sheets, so I tried that out and I really liked it. I’ll make three to four copies of the same image. If one sheet goes, the whole thing is dead. I’ll lose three to four in the process. Usually there’s only one that I really like and that I’m happy with. I use organic things to tone the print – Arabic coffee for the Palestinian ones, the Standing Rock ones I used cochineal that I scraped off cactus, the Zapatista ones are toned with local coffee. I mount all my sheets on acid-free honeycomb board with clay on one side. I weld a steel frame and I put caulking all around the inside, put in the photograph and then I pour 2 gallons of UV acrylic resin over the top. And then I put the letters that the person wrote on the first layer of the resin… …I spend 1.5-2 days sanding the acrylic down until there’s a slight vignetting. When I’m done I feel a strong connection with my subjects… …I hope to honor the people that I photograph.”

“It’s a stupid process, but I love every minute of it… …Everything today seems to be about cutting down the process with shortcuts and I’m really enjoying going the opposite direction. For the Us & Them project from the time I started the project until I got one photograph was a year and a half and that was working exclusively on that project.”

© Wayne Martin Belger, “Us & Them, Kara Tepe #1,” 48″ x 60″ print from 9 sheets of 16″ x 20″ silver gelatin paper, toned with cochineal, prickly pear tea, and Arabic coffee. 1 of 1, 2015

© Wayne Martin Belger, “Us & Them, Palestine #1,” 48″ x 60″ print from 9 sheets of 16″ x 20″ silver gelatin paper, toned with cochineal, prickly pear tea, and Arabic coffee. 1 of 1, 2017

© Wayne Martin Belger, “Us & Them, Standing Rock #1,” 48″ x 60″ print from 9 sheets of 16″ x 20″ silver gelatin paper, toned with cochineal, prickly pear tea, and Zapatista coffee. 1 of 1, 2017 Photo of Chief Arvol Looking Horse of the Sioux Nation taken in the Oceti Sakowin DAPL resistance camp in Standing Rock, North Dakota.

© Wayne Martin Belger, “Us & Them, Moria #2,” 48″ x 60″ print from 9 sheets of 16″ x 20″ silver gelatin paper, toned with cochineal, prickly pear tea, and Arabic coffee. 1 of 1, 2017 Photo of an Afghani refugee in the food tent of the Moria refugee camp in Lesbos, Greece.

© Wayne Martin Belger, “Us & Them, Zapatista #3,” 48″ x 60″ print from 9 sheets of 16″ x 20″ silver gelatin paper, toned with cochineal, prickly pear tea, and Zapatista coffee. 1 of 1, 2017 Hilda, backed by the Zapatista Army. Hilda is the mother of one of the missing 43. 43 students that were on a bus heading to a protest in Mexico City when it was stopped by local police. All 43 students have never been seen since. Her “Words from the Heart” : “Why? I will keep searching for you until my heart stops beating. I love you my Manuel.”

© Wayne Martin Belger, “Us & Them, Zapatista #2,” 48″ x 60″ print from 9 sheets of 16″ x 20″ silver gelatin paper, toned with cochineal, prickly pear tea, and Zapatista coffee. 1 of 1, 2017 Zapatista commander with his platoon in a Zapatista military camp in Chiapas, Mexico close to the Guatemalan border. He declined to write a “words from the heart” message for the photo. He was a little busy.

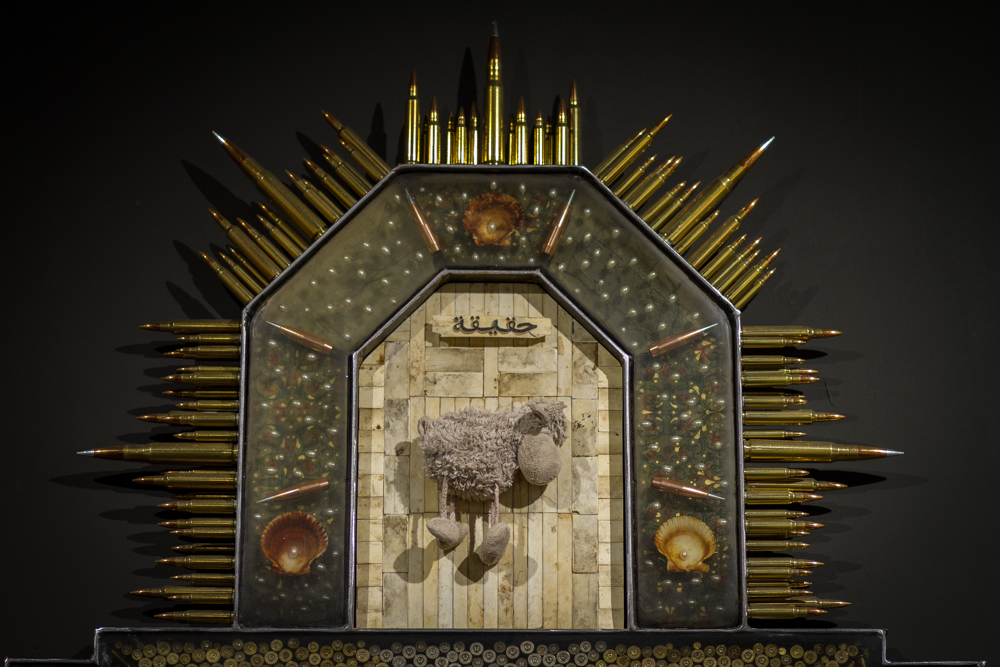

Wayne’s exhibition installations bring all of these elements together in one place to create a powerful experience for those lucky enough to see his work in person. In addition to exhibiting the prints and camera together, he creates an altar of sorts for the camera to make it a focal point of the experience. Wayne often incorporates additional artifacts significant to the subject matter of the project into these altars. He recently exhibited an installation of Us & Them at the San Diego Art Institute.

“In the middle of the “Us & Them” installation is a door that was from the Kara Tepe Syrian refugee camp is Lesbos, Greece… …The door was once the front door to a UN structure inside the refugee camp that was used for registering and fingerprinting new refugees arriving to camp. When many of the refugees would leave the registration room, they would wipe the finger printing ink off of their fingers and on to the door. I thought the door was amazing! It had so much history and stories of transition, I thought it should be preserved.”

The installation also includes a stuffed animal left behind after unloading a refugee boat, a piece of the fuel line from a German V2 rocket that exploded in London during WWII, a collection of smashed Springfield bullet shells from an Indian/US Cavalry battle in the 1870s, and more.

© Brian Van de Wetering, “Us & Them” small museum installation at the San Diego Art Institute. Large museum installations will include 50 to 80 48” x 60” portraits.

Since the close of the exhibition in San Diego, Wayne and the camera have been back on the road meeting and photographing new communities of marginalized people. First, there was an “Us & Them” shoot inside an ICE immigration center in Arizona.

© Shannon Smith, Wayne shoots a portrait of a young man from Honduras in an ICE facility in Arizona.

© Shannon Smith, In an ICE facility in Arizona, a young Mongolian child is fascinated by Wayne’s camera. The Mongolians crossed the border with the Hondurans, guilty of nothing more than trying to secure a better life for themselves and their families.

© Wayne Martin Belger, Scanned negative from the “Us & Them” photo shoot at an ICE immigration facility in Arizona.

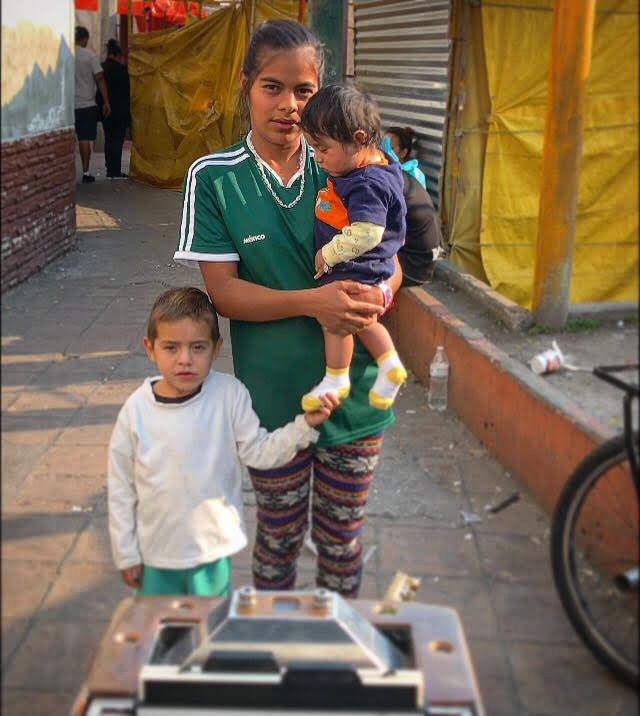

On Thanksgiving Day and Black Friday there were sessions in Mexico City and Tijuana to photograph people in the Migrant Caravans.

© Wayne Martin Belger, “Us & Them” Migrant Caravan photo shoot of woman with two children at a migrant housing facility set up by Father Alejandro Solalinda in Mexico City.

“Not a “Middle East terrorist!”

Not a “bad people!”

Not a “criminal!”

Not a “Bad Hombre!”

Not coming to “take YOUR job”

Sometimes people just want to continue breathing and will look for a place to do so. I am thankful that my ancestors from Ireland had the insight to do exactly what this young family from Honduras is doing.”

© Luis Alberto González Arenas, An “Us & Them” photo shoot of Father Alejandro Solalinde. Solalinde is known as “The most recognizable priest in Mexico.” He’s a human rights champion that has survived assassination attempts from the cartels and government because of his commitment to the human rights of migrants.

Tragically, the camera and all the undeveloped negatives from these sessions were stolen in Mexico City and have not been recovered.

“The “Us & Them” camera, all of the film from all the migrant caravan photo shoots in Tijuana and Mexico City where stolen form our car tonight while we had dinner on the way home from the shoot. My Passport and all of the gear I use to shoot photos in the field are gone too. I feel gutted. In the last 4 years the camera and I have traveled around the world many times, in very difficult conditions and worked hard to bring a positive message and awareness to millions. In the coming year we were heading back to the Zapatista compounds of Chiapas, the Palestinian territories in March and in the summer of 2019 to Nigeria to make beautiful inspiring portraits with the young woman that were kidnapped by Boko Haram… …I lost part of me and I feel sick… …I met so many amazing humans in life transition and listened to their vulnerable, beautiful and heartbreaking stories.”

© Luis Alberto González Arenas, Inside the car where the camera was stolen, Wayne collects broken glass to use as an artifact for a new “Us & Them” camera.

© Luis Alberto González Arenas, Wayne contemplates the future of the “Us & Them” project at Frida Kahlo’s house in Cayoacan, Mexico shortly after the theft of the camera.

Wayne has a tattoo on his chest in Aramaic that, in translation, reads: “In Death I Bloom.” After the passing of the initial shock and despair, Wayne has started work on a new camera to continue the project. Friends and supporters have already begun sending him artifacts for the new camera, which will include broken glass from the car where the first camera was stolen, black lava rock from a wall built by Diego Rivera, and steel cut from the US/Mexico border wall.

“The new creation may be more intense than the first…”

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Yana Nosenko: BedsJanuary 30th, 2026

-

Anna Guseva: The Black Night Calls My NameJanuary 26th, 2026

-

Madeleine Morlet: The Body Is Not a ThingJanuary 19th, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Yang JaeMoon: Blue JourneyJanuary 15th, 2026

-

Yorgos Efthymiadis: The James and Audrey Foster Prize 2025 WinnerJanuary 2nd, 2026