Maja Daniels: Storytellers

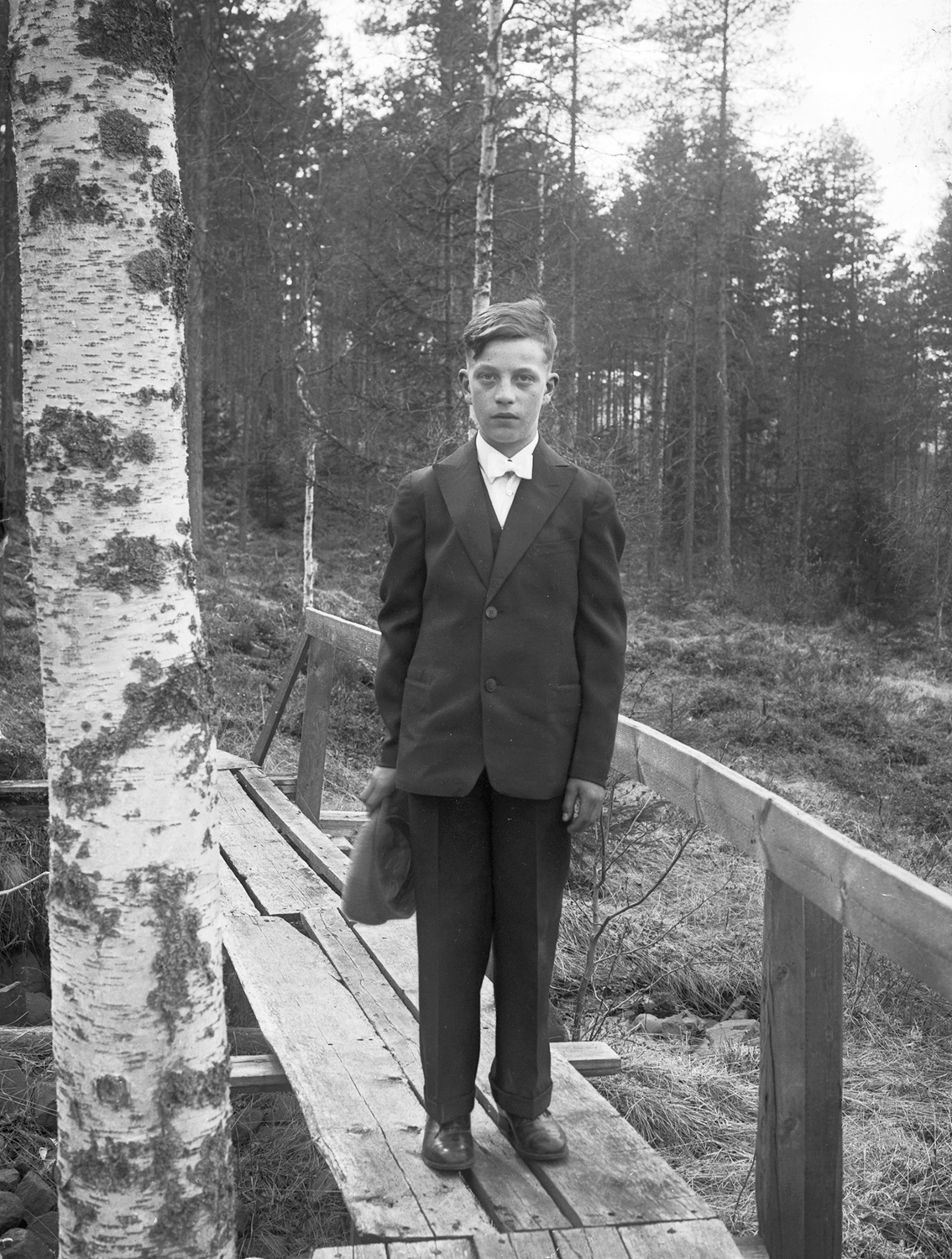

Dalia Tenn Lars Persson (1878-1938), from Elf Dalia by Maja Daniels, Courtesy of Elfdalen Hembygdsförening (EHF)

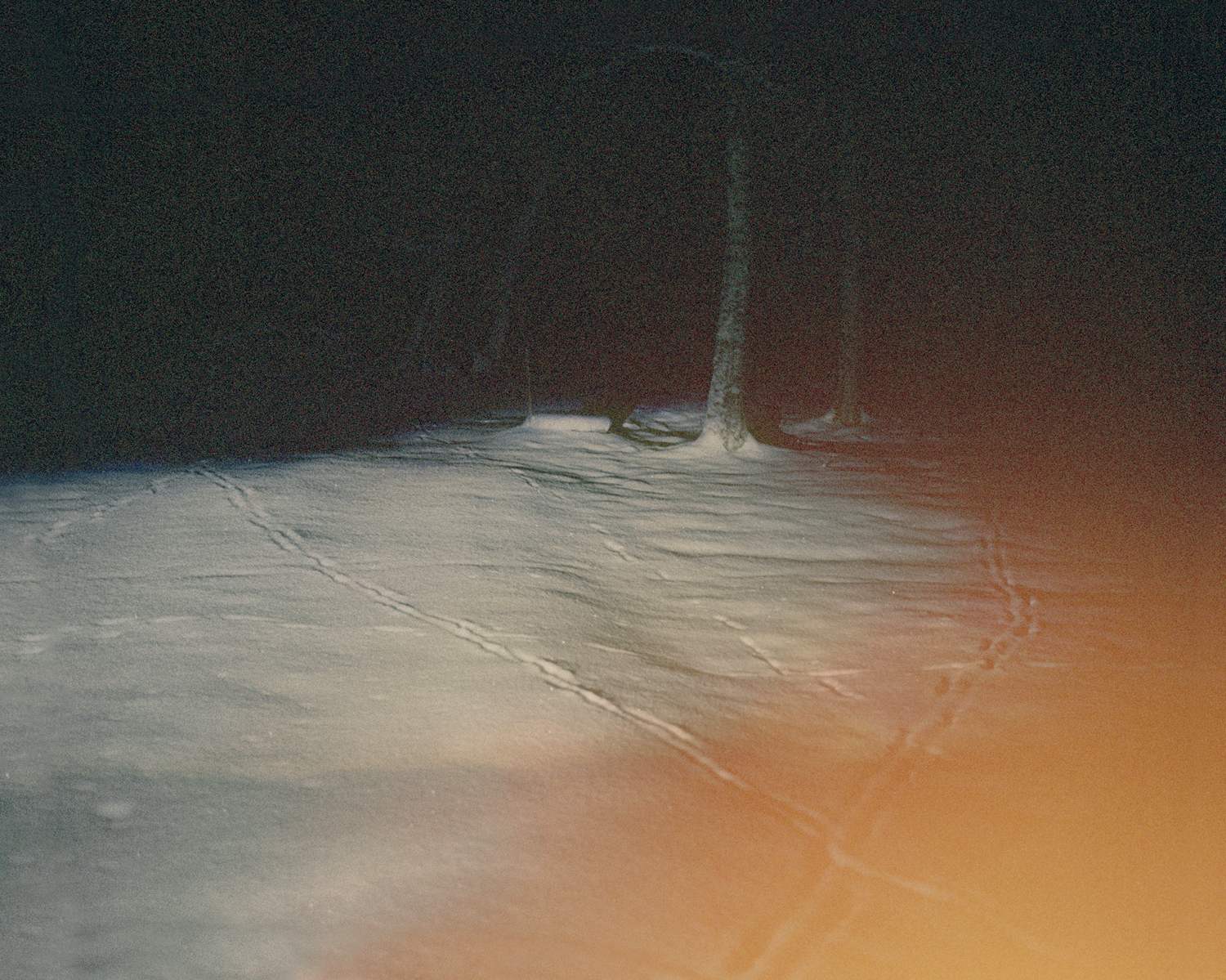

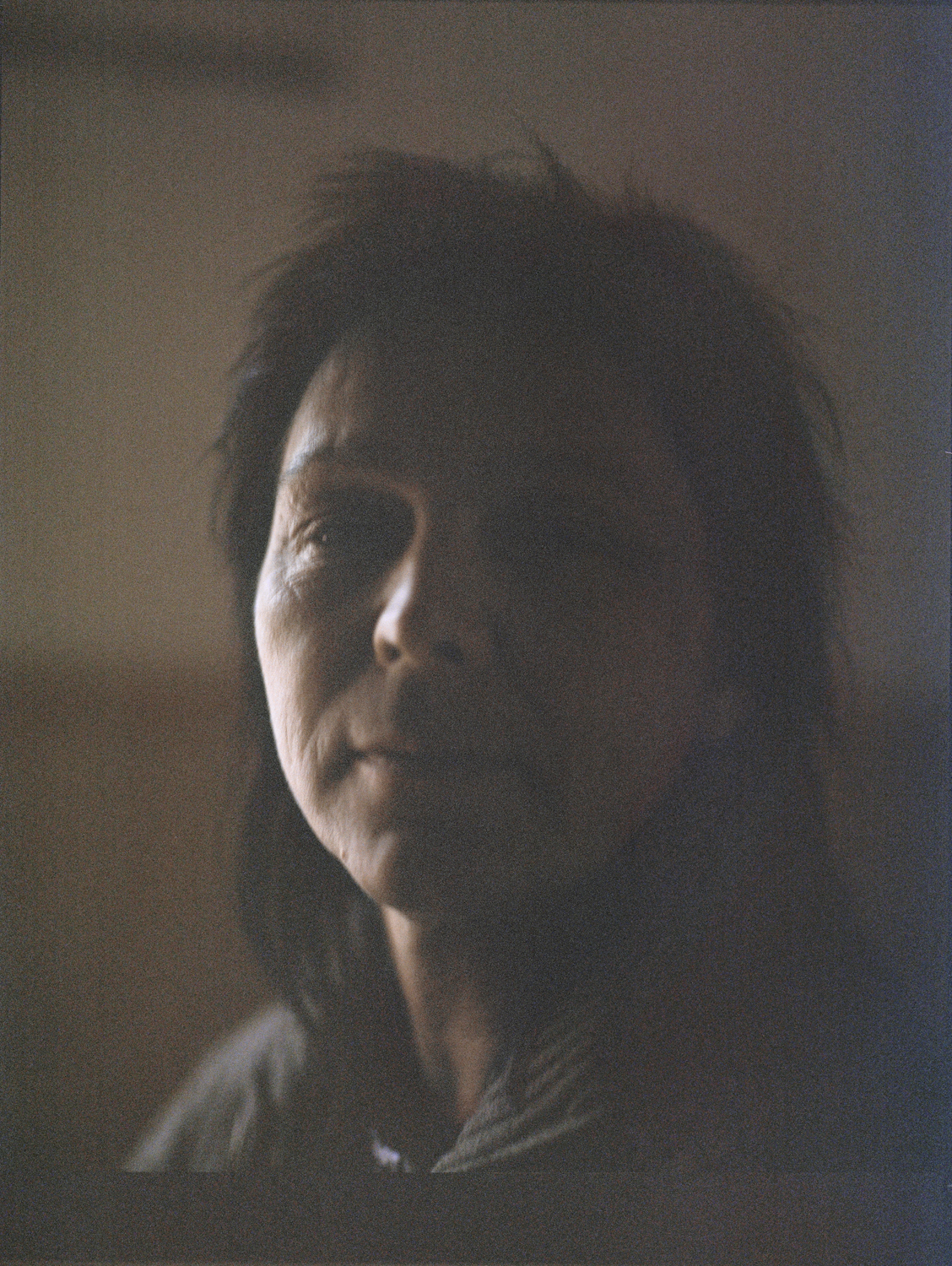

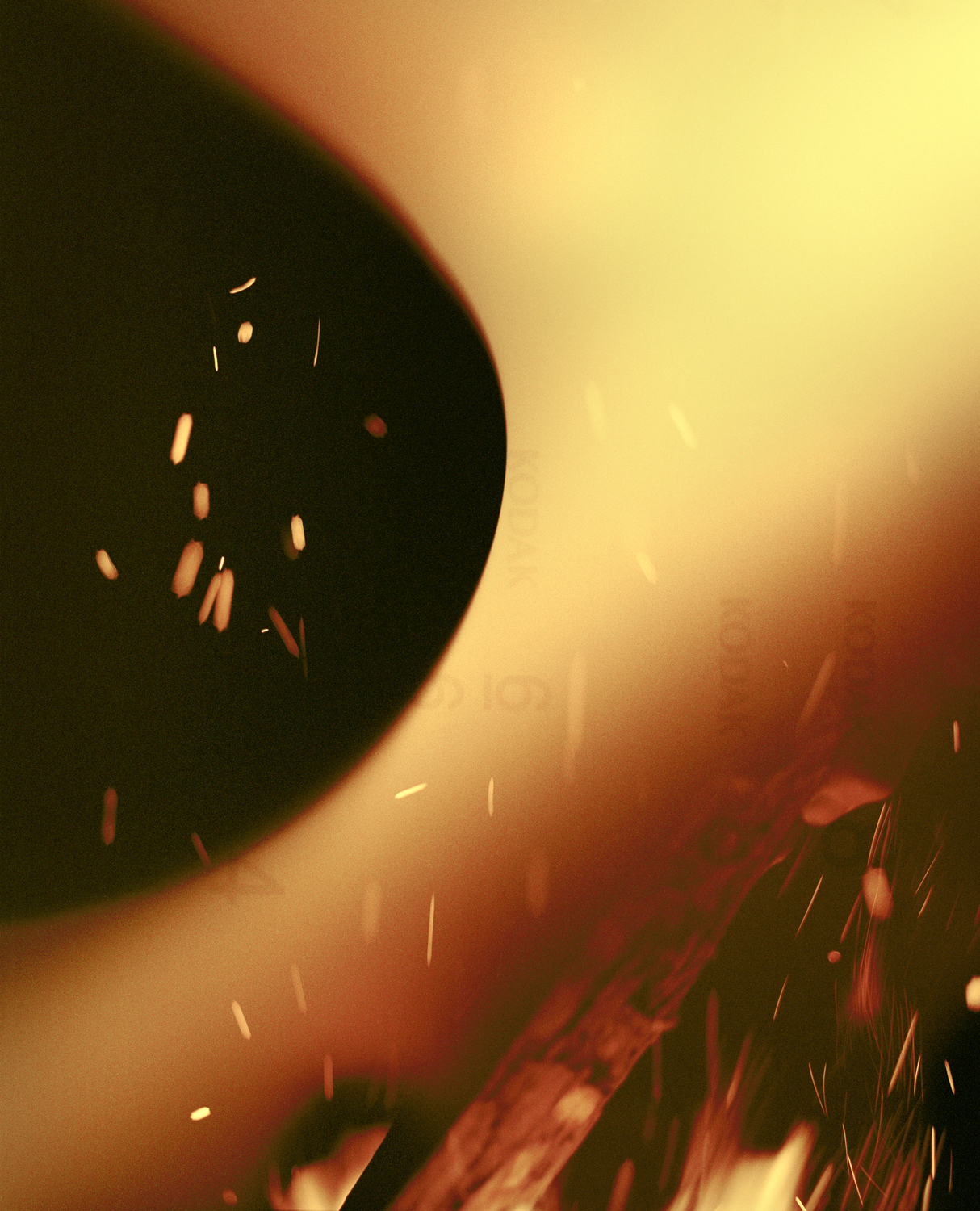

Through a photographic collection of light leaked landscapes, obscured figures, and archival imagery from the early 1900’s Swedish photographer Maja Daniels explores an enigmatic rural community and the mysterious preservation of the ElfDalian language by creating a visual language all her own. The work defies linear ideas of time that contain a past and present and initiates a dialogue with the images of Tenn Lars Persson, a photographer whose monochromatic scenes oscillate between baffling and banal are juxtaposed beside Daniels. Despite the subversion of a chronological time structure and the inclusion of a second narrator, the series Elf Dalia contains a surprising amount of intuition and natural rhythm, perhaps due in part to the cyclical inclusion of the waxing, waning moon. By engaging across mediums including sculpture, film, and a photobook, Daniels has created an expansive work that is at once contemporary and historical, an ethnography and a seance.

Maja Daniels (b. 1985) is a Swedish photography-based artist. Her work is influencedby her studies in sociology and can be described as a multi-layered academic and artistic practice that includes sociological methodology, sound, moving image and archive materials, aiming to further explore each medium’s narrative and performative functions.

Currently based between London and Gothenburg, her work has been exhibited in Paris, London, New York, Amsterdam and Bilbao. She is the recipient of numerous awards, such as the Codice Mia Photographic award 2019, the 2013 Contour by Getty Portrait Prize and the Taylor Wessing Portrait Prize 2011.

She has received grants, fellowships and bursaries to develop her personal projects and she is regularly lecturing about her work. She also work on commissions for the weekly and monthly press worldwide and she collaborates with cultural institutions, using photography as a tool within wider research.

Her first book “Elf Dalia” was published by MACK books in spring 2019. The book quickly received international acclaim as it was nominated for the Aperture-Paris Photo First book Award 2019 and was listed as one of the best books of the year by The Guardian, The Financial Times Magazine, The New Statesman, ASX and a number of online publications. It also won the Swedish Photo Book of the Year Award.

Elf Dalia has since expanded into an exhibition (including a video installation) that is currently touring internationally. Maja made her first short film “My other Half” in 2015 and her second one “My friend Barbro” (2018) won the Fotografiska Documentary Award the same year. She just completed a new short film, “Hauntings” that is to be premiered in 2020. Currently, Maja has received a grant from the Swedish Authors Fund to work on her

second book.

My work can be described as a multi-layered academic and audiovisual artistic practice that includes working with photography, sociological methodology, sound, moving image and archive materials, aiming to further explore each medium’s narrative and performative functions. I work across various platforms making artist books, site-specific installation work, screen based cinematic work as well as sculptural work for the gallery space.

With a background in sociology, my work is grounded in a critical and creative engagement with the politics of aesthetics at its core, looking at societal aspects and frameworks that relate to questions of heredity, family relations and identity construction. I am interested in the function of the image; what images do and what they offer to us as individuals as well as a society. By conjuring up new ways of relating to and looking at the world, my aim is to go beyond that which is initially considered “given” and to engage with the visual in ways that both question and expand its narrative potential.

My research interest lies in the invisible ties between history and the present and how the representation of historic events and personal memories can reshape how we read and understand contemporary events. I aim to create visual expressions that challenge a linear and chronological concept of time and explore counter hegemonic narratives in order to challenge established knowledge and resculpt or reconfigure the boundaries of the world as we traditionally know it, often starting out in the shadows, in the less visible. – Maja Daniels

In your biography you reference your work being informed by your former studies in Sociology. When did you first begin engaging with the photo making process and how does your background in sociology influence the way you work as a photographer?

I have always mixed my studies in sociology with a photographic practice so in a way it was my engagement with the visual that propelled me to seek out further theoretical engagements in order to feel confident to speak about and engage with my surroundings in what I felt was a creative, critical and meaningful way.

I’ve read in other interviews that you spent time growing up in Älvdalen. Can you share any prominent memories from that time in your life? Growing up, were you aware of the enigmatic nature of the place and its language?

We would spend summer and winter breaks in Älvdalen and me and my brothers would roam around in the forest. To me Älvdalen does not appear enigmatic since I have grown up in it. But, the really remarkable thing that struck me early on was my grandparents secret language (Elfdalian). They used it to communicate among themselves, often about things I was not supposed to hear. They had been taught that Elfdalian was ugly and that it would be better to speak Swedish to their children so sadly that is what they, and many others in their generation did.

As I began immersing myself in this work, I became interested in exploring the cultural value of a language and how the act of speaking reproduces a specific worldview. I wanted to engage with these notions visually as a way of creating a personal connection to these questions.

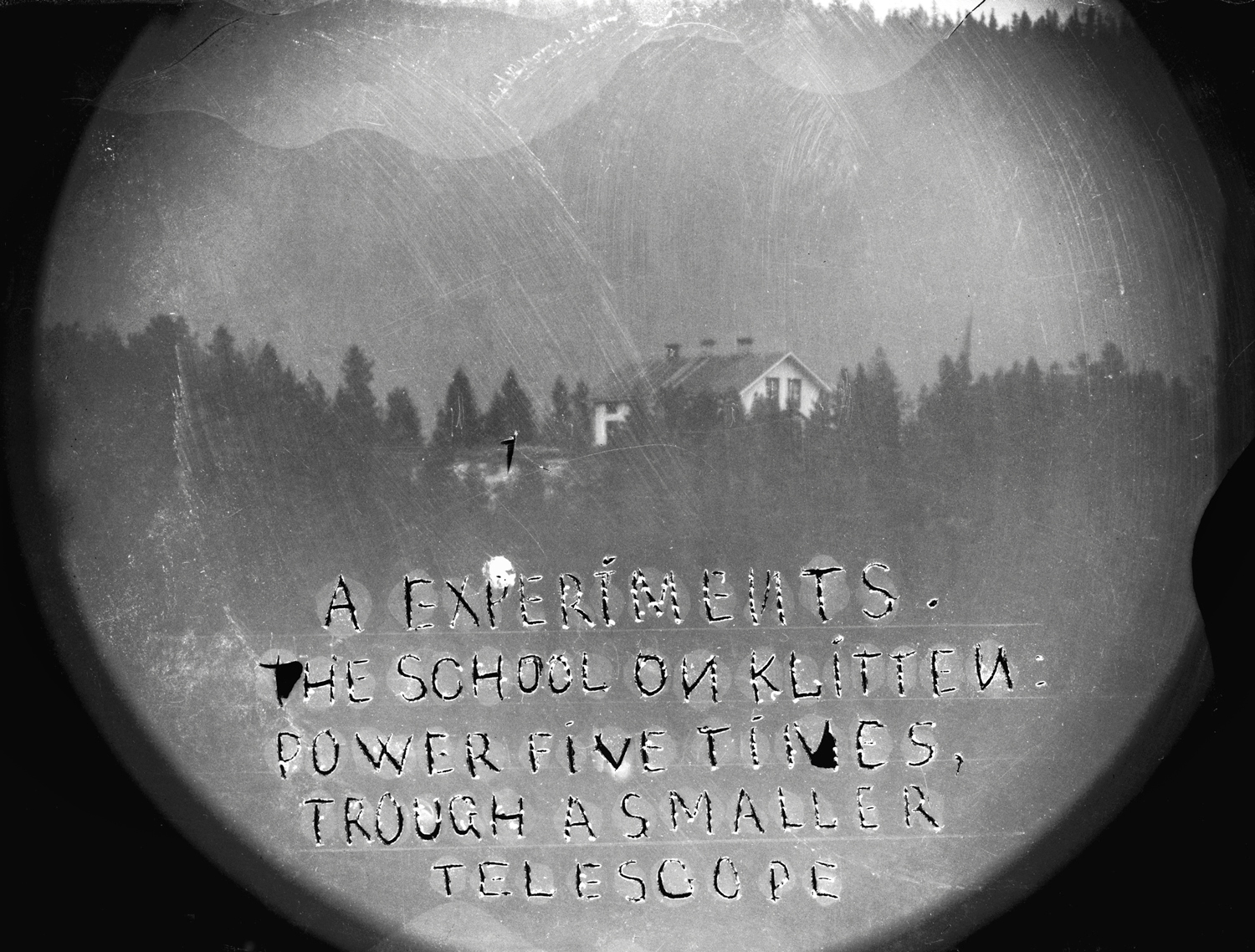

Tenn Lars Persson (1878-1938), from Elf Dalia by Maja Daniels, Courtesy of Elfdalen Hembygdsförening (EHF)

I love what you wrote in your statement about creating, “visual expressions that challenge a linear and chronological concept of time”. What experience did you hope to achieve by subverting the traditional presentation of information? Why is this important to your way of storytelling?

It is part of my belief in the fact that the Western construct of thinking in binaries is limiting the way that we can engage with and understand the world, so it is part of my ambition to provide visual experiences that break with this way of thinking and provides alternative worldviews.

From what I’ve seen your earlier works fit more comfortably within the documentary tradition. What inspired the shift in your practice towards the abstract and ineffable?

It is hard to pin-point one particular reason, I guess it is just part of my evolution as an artist, photographer and human being. I have always been interested in hybrid formats and to shake up and mix genres. One important part of my continued engagement in academia has revolved around the ethics of visual representation and an ambition to somehow push the envelope of how we speak about contemporary issues in alternative ways so I have been trying to think about the image in relation to this. This “shift” (perhaps much more noticeable to you than to me as these things are ongoing processes) was probably also propelled by the choice of going back home and working on a topic that is much closer to home. After spending 11 years living in Paris and London, I decided to move to our family cabin in the Älvdalen woods and ended up spending 3.5 years living and working there. Going back home, focusing more on the invisible ties between past and present while spending time in nature shaped the way I make and think about photographs for sure.

As a body Elf Dalia is given a new dimension by the inclusion of Tenn Lars Persson’s work. Despite being taken more than a century apart his images seem to be in close conversation with yours. How did the project change upon discovering and choosing to include his images? Were any of your photographs taken in direct response to his pictures?

I discovered Tenn Lars’ images early on in the process and immediately knew they had to be part of the project so they have been co-existing, influencing and speaking to me along the way.

I have tried to think of the concept of language as a way of relating to what a ‘magical experience’ could mean in the contemporary world. This, to me makes the idea of magic less about something supernatural or mystical, or an aspect of modern or post-modern crisis, but rather focuses on an emotional relationship with place through notions of ancestors, folk beliefs and myths. By mixing my contemporary images with Tenn Lars’ archive my aim was to try to carve out a timeless space whereby mystery, strange events, becomings (past becoming present and vice versa, man becoming animal etc.) and humor can co-exist and where we can think of a ‘magical experience’ as a creative expression, a sort of language.

Tenn Lars Persson (1878-1938), from Elf Dalia by Maja Daniels, Courtesy of Elfdalen Hembygdsförening (EHF)

Artist books are in many ways objects of finality. Now that Elf Dalia has been published how do you continue to engage with Älvdalen’s evolving story?

I think about my work more like an ongoing process which results in multiple iterations. The book Elf Dalia is one but I have also built on it by expanding it into an exhibition that includes a film installation, and more recently another kind of publication in the making. I find it liberating to move away from the idea of a defined project and to see it more like a fluid engagement lead by desire.

With the disappearance of a language comes the loss of a region’s history, folklore, and worldview. Aside from the witch hunts can you offer further lore that has defined Älvdalen’s essence?

Both the notion of photography and archive are so closely linked to processes of remembering and forgetting and memory as a concept is in my opinion a good one to creatively engage with rater than trying to fixate or fully understand since its very nature is that it is fluctuating, deceiving, incomplete. In Elf Dalia I use aspects of local history to activate some aspects of the Elfdalian collective memory but I also want to encourage free associations within the reader, interpreted and influenced by their own imagination.

To me, the direct engagement with specific events from Älvdalen’s past are grounded in an urge to question them, to look again and to look differently. These “light leaks” that appear throughout the book became a way for me to allow for something else to be present in the work, to hover over it and to call for a certain hesitation, an unknowing of what we know as ‘History’, or of the photograph as ‘document’.

By reimaginging local history and reappropriating Tenn Lars’ images I am in some ways offering up new readings that in turn opens up to multiple more readings. I want the work to question both that, which has already been established as known and that, which has been discarded as not known or not true. By restaging the act of looking at these archival images, I find that it provides and interesting way of reinforcing both presence and absence, to make different layers of meaning and to allow for the viewer to employ their own imagination in relation to ideas about the past and how we traditionally tend to think of “the Archive” as a somehow neutral space. Of course it is not.

I’m curious about the landscape of Älvdalen both geographically and culturally. Your words and images describe a place of great tradition and obscure enchantment, yet as a community it is not isolated. How is the influence of the modern world changing Älvdalen?

Älvdalen is not and has never been an isolated community. Remote yes but never isolated. Change is a natural occurrence and I have always been fascinated with the mix of the old and the new. Preservation is a complicated concept especially when it comes to culture and language since it prevents an ongoing evolution and I think that in Älvdalen both culture and language has proven to be resilient precisely because they have been able to change and evolve with the times.

Today, Älvdalen has a vibrant American-inspired car culture for example with a Motor and Music festival happening in August every year. The local forest foundation initiated a grant a few years back to encourage young Elfdalian-speakers to use the language. If they pass a test they get approximately 500 Euros to spend and very often that money goes into “pimping” some sort of ride which is such a great way to think of how past and present can coexist in a very hands-on, practical way.

In the time of Covid-19 and social distancing how has your practice changed? Do you find yourself and your work turning inward?

Recently my work has been focused on filmmaking, both in the shape of sculptural installation works and by making a single-channel short film to be viewed in the cinema. It is my interest in the photobook and in the distinct difference between still and moving images that made me start thinking more about how to work with and combine the two. Recently I have started to work more sculptural as well. All of these processes have placed me in a prolonged state of research which has been reinforced and intensified by Covid-19. However, I have received a working grant to produce a new book so am about to break out of my current state of research hibernation and to go to Älvdalen to spend two months making work. I am really looking forward!

Tenn Lars Persson (1878-1938), from Elf Dalia by Maja Daniels, Courtesy of Elfdalen Hembygdsförening (EHF)

Tenn Lars Persson (1878-1938), from Elf Dalia by Maja Daniels, Courtesy of Elfdalen Hembygdsförening (EHF)

Tenn Lars Persson (1878-1938), from Elf Dalia by Maja Daniels, Courtesy of Elfdalen Hembygdsförening (EHF)

Tenn Lars Persson (1878-1938), from Elf Dalia by Maja Daniels, Courtesy of Elfdalen Hembygdsförening (EHF)

Macaulay Lerman was born in the Spring in Southern California and raised in New England. As a young adult he traveled throughout the US and Canada hitchhiking, hopping freight trains, and driving his camper van. While Lerman rarely carried a camera during this time, he developed a practice of documentary storytelling through extensive journaling. To this day he remains fascinated by fringe communities and alternative ways of living, perceiving, and being in the world. While his process is largely ethnographic, in the sense that he immerses himself in the worlds he depicts, he is far more interested in emotional realities than hardlined physical truths. Above all else he values dreams and memory. A photograph exists somewhere between the two and this is why he is drawn to the medium. Lerman earned his BFA in Photography and Documentary Studies from Green Mountain College in Poultney, Vermont. Since then he has shot for a variety of organizations including the Slate Valley Museum and the Vermont Folklife Center. His work has been exhibited internationally in solo and group exhibitions, and featured in publications including It’s Nice That and Anywhere BLVD. Lerman currently resides in Burlington Vermont where he is an active member of the Wishbone Artist Collective.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Yulia Spiridonova: Wayward SonJanuary 29th, 2026

-

Ed Kashi: A Period in Time, 1977 – 2022January 25th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026