Erica Cheung: Minor Matter

This week, I am excited to introduce five new Lenscratch Content Editors who will be providing expanded perspectives to our site. Houston photographer, Erica Cheung, brings a rich perspective as a visual artist, curator, and photographic administrator with an interest in promoting and elevating the Asian American voice and experience. Her series, Minor Matter, explores the Asian American experience from three perspectives: the personal, the media, and the broader histories and legacies of her community. An interview with Erica follows.

Erica Cheung is an artist, poet, and environmentalist from New Jersey based in Houston, Texas. Her practice explores Asian American identities and the tensions that arise through these identities’ various intersections with popular culture and media, traditional immigrant family values, the environment, and race relations in America. Her work manifests itself in a range of media, including photography, text, collage, and experimental sound and video.

Erica is currently responsible for social media coordination, inventory and sales management, and exhibition administration at Foto Relevance, a contemporary photography gallery located in Houston’s Museum District. She is also involved in archiving the work of photographers and FotoFest founders Fred Baldwin and Wendy Watriss for the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin. She received a BA in English and Visual & Dramatic Arts with a concentration in Film/Photography from Rice University.

Minor Matter

Minor Matter (working title) is an ongoing, interdisciplinary assemblage of text and visual art that revolves around facets of Asian American existence in contemporary America. Colloquially deemed as the ‘model minority,’ Asian Americans often face an experience of contradictions. We are lauded for our successes (which are then used to disparage other systemically marginalized minorities), but are also consistently left out of our country’s narratives, both historically and in the present day. We are painted as hard working and diligent, but are simultaneously ignored or mischaracterized in politics and in media. Minor Matter attempts to make sense of the dissonance, weaving together poetry and photography as a means of offering multiple avenues to reckon with a past of immigration and discrimination, a present of agitating for precise and diverse representation, and a future of uncertain optimism. – Erica Cheung

Tell us about your growing up and how you came to photography?

I came to photography because I’m pretty hopeless with most other media—drawing, painting, printmaking, you name it. In the wake of poorly drawn stick figures, I was lucky to find photography. The processes associated with the medium just ended up making the most sense to me, and I loved how the click of a shutter gave me little, transportable pieces of the world to tinker with.

I had the marvelous fortune of attending a high school that had its own darkroom. Under the guidance of a teacher who was overwhelmingly enthusiastic and generous with his knowledge, I spent hours developing film from my dad’s Minolta camera and making prints. This early foray into photography taught me how to be patient and methodical in my work (though I have far from perfected these skills). In college, I studied digital photography with a stunningly kind roster of professors (Allison Hunter, Geoff Winningham, and Paul Hester), which gave way to experimentation with everything from microscope photography and bookmaking to image animation and printing on silk.

In all honesty, I grew up feeling ashamed about my affinity for the arts. As is the case for many artists, I was conditioned to feel that photography was best manifested in my life as just a hobby, and that I should focus my attention on a career path that was ostensibly more lucrative—medicine, finance, tech, etc. Well-meaning forces around me—my family, my educators, my peers both at my north Jersey high school and at a Texas university that is lauded for its prowess in the sciences—questioned my dedication to a realm which is arguably not the most diverse or easily navigable of fields. I was on a biology and pre-med track in college for a year before I flip-flopped over to the humanities. Sometimes I still question if this was the right decision—but the potential for growth and the increasing accessibility of photography/the arts excite me, and I’m more than thrilled to be a part of the fray.

As a Content Editor for Lenscratch, what are you excited to bring to the site?

A big thank you to Lenscratch for bringing me on board—it’s an immense honor to be a part of the team. I’ve been following the website for over two years now, and I am constantly impressed by how tirelessly the platform’s contributors provide thoughtful commentary on photography from all over the world. In joining as a Content Editor, my hope is to elevate and amplify the voices of the Asian diaspora—a community that I hold dear, and a community that I am constantly trying to learn more about through a creative lens. At the same time, I hope to offer my support to all underrepresented and overlooked voices, with the intent of further diversifying and building Lenscratch’s role as an educational resource in the photographic community.

How important is writing to your practice?

I’d say it’s just as important as the visual side of my practice. Writing has always been a refuge to me; I’m infinitely better at putting pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard) than speaking out loud. Writing is where I get to play with language in ways that comfort, trouble, and bring unlikely things together into the same domain. When I can’t visualize, I write, and when I can’t write, I visualize. When I can’t do either, I try to read and watch and learn.

Who and/or what inspires you?

There’s a myriad of wildly talented people who I turn to when I find myself looking to be inspired in certain ways. For bravery and vulnerability, I turn to writers Claudia Rankine (Citizen; The White Card) and Anne Carson (Nox). Both use image and text in ways that gut punch me.

For gentleness and grace, I gravitate towards the poems of Li-Young Lee (“Persimmons” is my absolute favorite poem ever written). For humor, I seek out Matthew Olzmann (Mezzanines) and graphic memoirist Mira Jacob (Good Talk). For thinking about the strangeness of language and the richness of the land around us, I rely on the poems of Natalie Diaz and Ilya Kaminsky, as well as C Pam Zhang’s new novel How Much of These Hills Is Gold. For reminders of why I love the complicated place I’ve called home for six years, I look to Bryan Washington’s stories about Houston. For joy, I think there’s nothing better than The Sweet Flypaper of Life by Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes.

I’d also be remiss if I didn’t mention the people directly in my life who also inspire me: my parents, my sister, my friends, my educators, and the artists and team at Foto Relevance.

Your series, Minor Matter, is a personal telling of family, immigration, and memory. What do you want the reader/viewer to take away from this work?

I think it depends on the reader/viewer. For those coming at the collection from an Asian American or another immigrant/diasporic perspective, I hope there is a sense of being seen and affirmed. A sense of “hey, that feeling you’ve felt? I’ve felt it, too.” I hope that the work resonates with these communities in ways that validate and acknowledge them.

For those coming at the series from a point of view that might be far removed from my own, I hope the work elucidates what it’s like to constantly feel othered in the place that you call home—while still trusting that there will be a day you can do so unconditionally. I hope that this calls forth an understanding that while the experiences I detail—and the experiences of those who have faced similar things–might be lightyears away from their own, they hold true just the same.

Tell us about the three parts to this project.

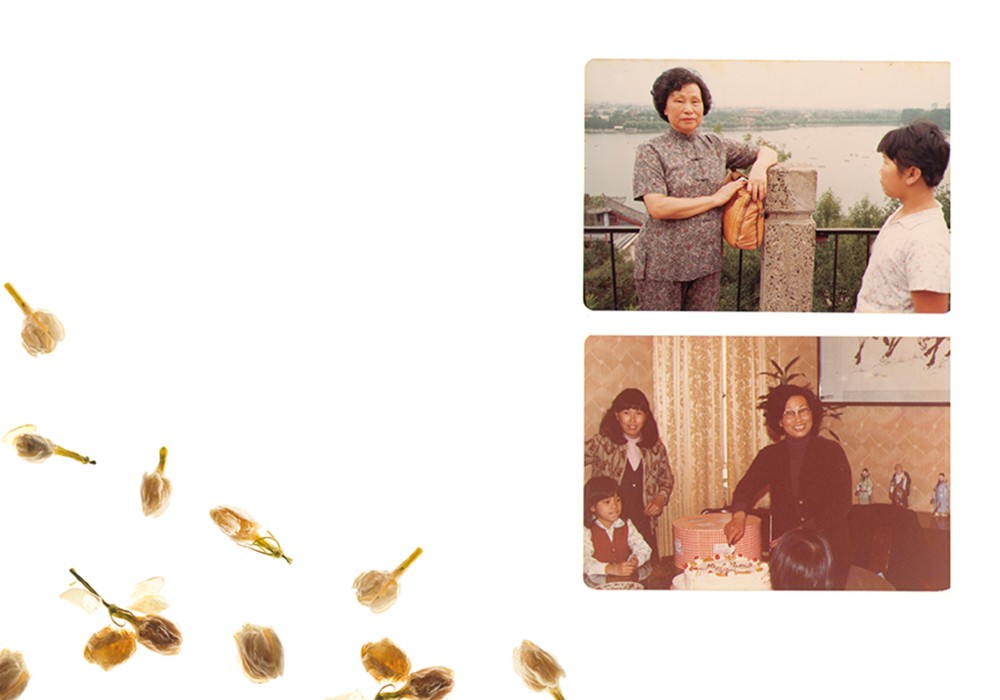

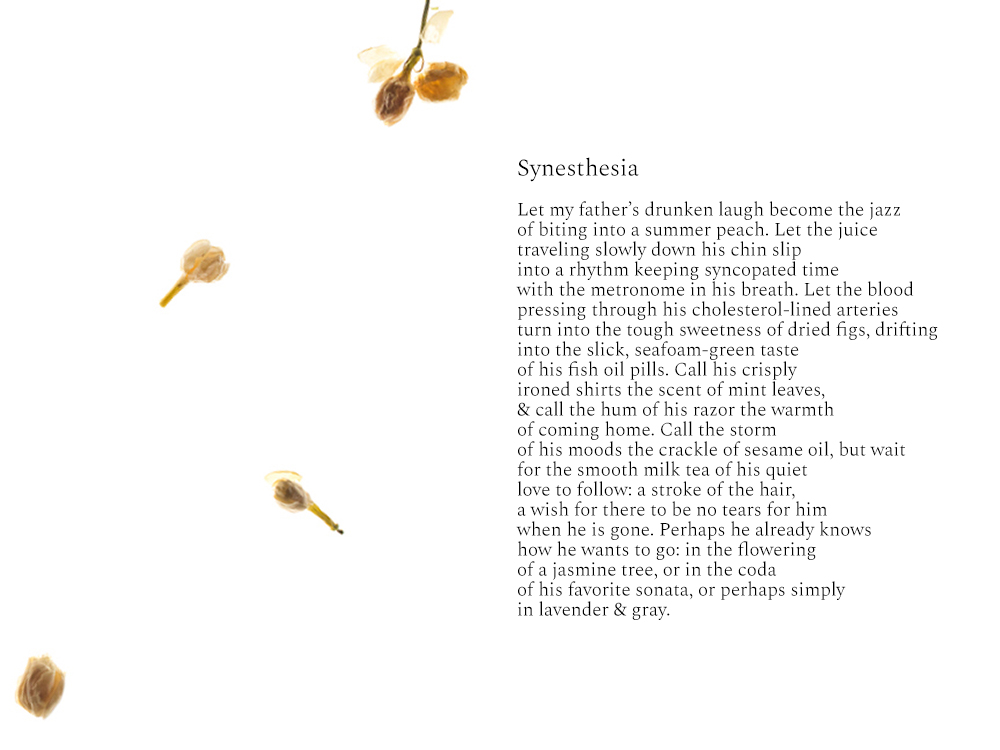

Part one of Minor Matter focuses on my personal family narrative. Accompanied by visuals of old family photographs and dreamy, flora-based imagery such as tea leaves, dragon fruit, and lychee, I imagine and reimagine my parents’ immigrant lives in the United States, putting language to their stories in an attempt to solidify them into concrete memory.

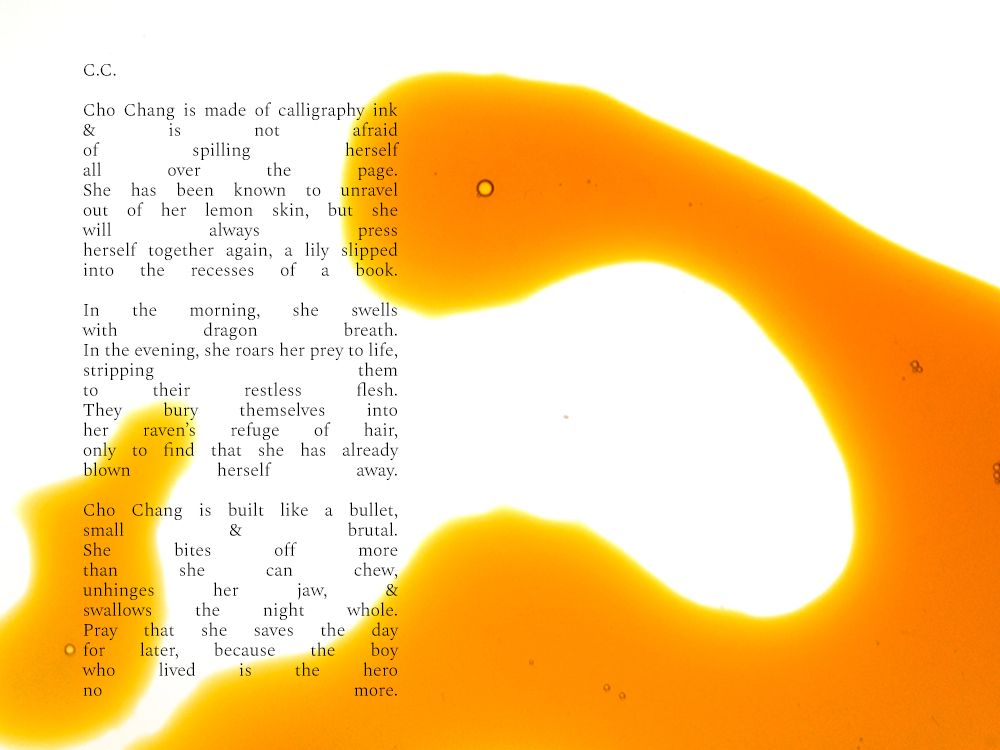

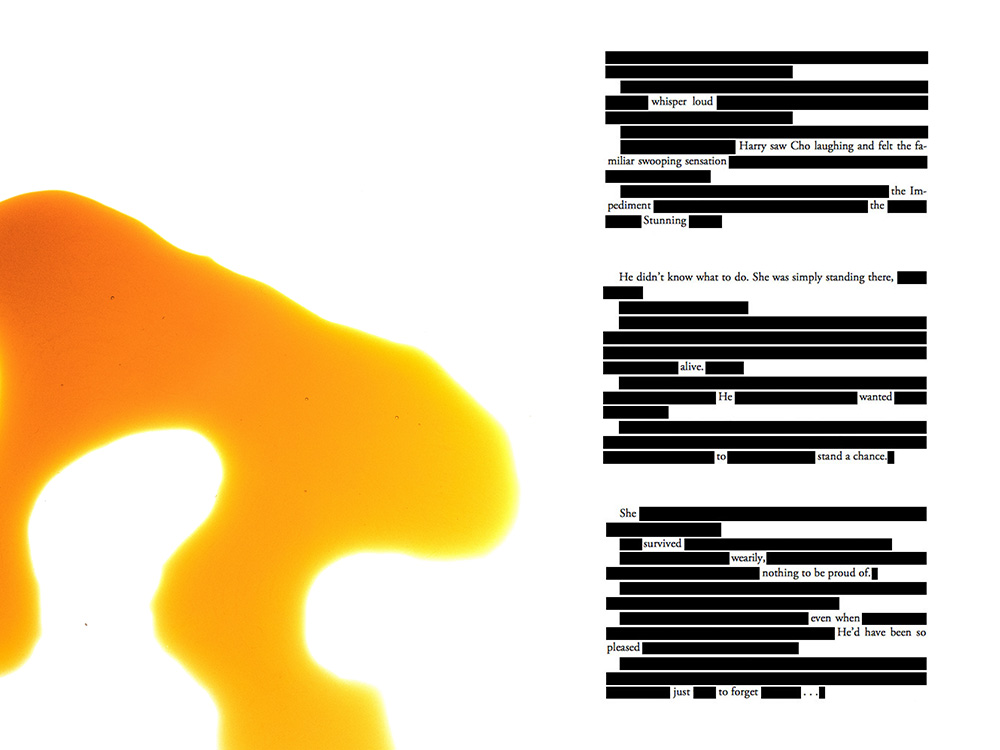

In part two, I think about and repurpose fragments of media that depict Asian American women in questionable ways—i.e. a quote from “The Chinese Woman” episode of Seinfeld, the character Cho Chang from the Harry Potter series, and film stills from the movie Dragon Seed in which Katharine Hepburn and her Hollywood counterparts appear in yellowface. With these materials, I address the subordination, fetishization, and erasure of Asian American women’s bodies in media.

Part three expands the discussion outward, considering my stories against the societal fabric of Asian America at large. I pair objects that I consider universal to my pocket of Asian America—i.e. lucky bamboo plants, chopstick wrappers, fortune cookies, and red envelopes—with poems that think about the broader histories and legacies of my community. Through this, I introduce a careful hope for a time when Asian American stories told by Asian Americans are ubiquitous and celebrated.

Has your family seen the project and what was their reaction?

We haven’t really spoken at length about it, but they’ve seen it, and they know that the project is important to me. As it expands, I know they’ll continue to support me in the ways that they can, and in the ways that they know how. I’m grateful in that regard.

What’s next?

I’d like to keep adding to the collection. There are so many more stories and concepts that I’d still like to try and negotiate through writing/visuals. I want to keep tackling the larger historical legacies that are intrinsically woven into American immigrant narratives; for example, I’ve been thinking a lot about what it means to be a product and beneficiary of colonialist efforts (my parents’ proficiency in English came about due to the British occupation of Hong Kong, setting them on a track to be able to both attend school and settle in the U.S.), while also denouncing and bearing witness to the repercussions of those efforts as they unfold in the present day (in 1997, the British yielded Hong Kong ‘back’ to China under the temporary “one country, two systems” arrangement—the termination of which spells doom for Hong Kong’s already eroding autonomy). I want to sink a little deeper into uncomfortable spaces like this one, if only to invite others to follow suit and reflect on the ways in which the worlds we’ve inherited are our responsibility—even if we didn’t directly create them.

More tangibly, I’m curating a group exhibition at Foto Relevance in Houston, TX, which is scheduled to open on October 2nd of this year. Entitled Now You See Me, the show will include the work of Jerry Takigawa, Priya Kambli, Tommy Kha, Jennifer Ling Datchuk, Leonard Suryajaya, and Tomiko Jones—six Asian American artists whose practices I admire deeply. Check out the gallery website for the latest information!

How has Covid altered your practice? Did you make new work or try new things?

I think COVID has challenged my practice in both positive and negative ways. I’ve had a lot of time to sit alone with my own thoughts, mulling over what it means to be someone committed to the arts. At times, I’ve felt acutely small and powerless (there are days when all I want to do is lay on my bed and stare at the ceiling fan). At other times, I’ve felt galvanized and ready to face the systemic issues that have been exacerbated by and during the pandemic, be they racial, socioeconomic, or otherwise. I’ve also been reflecting on the responsibility of creators right now. Artists have been expected and called upon to provide original content that soothes and unites us while we’re all far apart, but many artists are also financially and emotionally vulnerable in ways that make doing so difficult.

All of this to say: I haven’t really been making new work in the sense of writing poems or taking photos. Instead, I’ve been using this time to regroup and rethink the avenues in which I can use the tools already in my tool kit—my education, my practice, my network, and my platforms—to help others. I’ve been toying with the idea of graduate school, and am hoping to find an interdisciplinary and socially minded arts-related program that will help me reconfigure my corner of the universe into a place that is more just, equitable, and inhabitable for those around me.

Favorite meal you made during Covid?

It’s not a meal per se, but the Strawberry Spoon Cake by Jerrelle Guy on NYT Cooking. One of the first comments under the recipe appropriately sums up my own experience with the cake, reading “I ate this whole thing by myself. All of it.”

Finally, describe your perfect day—and don’t forget to tell us who is on the soundtrack!

Every once in a while, Houston will get a day that reminds me of the fall weather I grew up with in New Jersey—one of those days when the air and the light and the humidity finally gel together (right now we’re still in peak summer swamp season). Waking up to a cooler day like that and going for a run by the bayou, followed by breakfast and coffee with a friend, museum/gallery/public art hopping, and happy hour at a wine bar (remember those?) would probably be as close to perfect as it gets. Throw in a couple chapters of a good book and a handful of BoJack Horseman episodes, and I’m set.

As for a soundtrack—I’ve been listening to a lot of Glass Animals lately. I’ve also been tuning into Yo-Yo Ma’s ‘Songs of Comfort’ online cello series, which has been an absolute treasure.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026