Focus on Installation: Aimée Beaubien

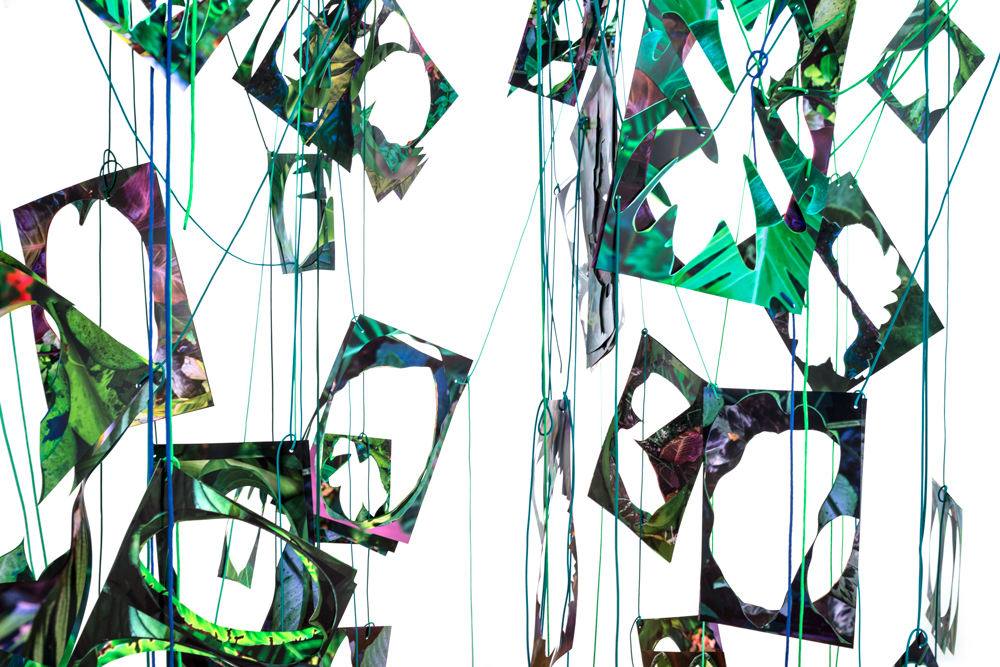

©Aimée Beaubien, Hothouse, 2015 cut-up photographs, paracord, mason line, miniature clothespins, grow light on fabric cord dimensions variable (sculpture on right) Rejoining Roger Brown – What’s happening now, 2015 cut-up photographs, miniature clothespins, candlestick, wooden table 59 x 22 x 20 inches Cutting Edges: Beaubien & Liang, The Pitch Project, Milwaukee, WI

Photography is always in transition and this week, we feature artists who are expanding how we think about and exhibit photographs. Aimée Beaubien is a wonderful example of uniquely using the medium as a way to re-see and experience 2 dimensional images, as she creates immersive, sculptural environments. She states: My own notational flashes exist as photographs and from my prints I create ephemeral paper structures that accommodate, attach, climb, trail, cling, spread, creep and rearrange within each new exhibition environment: loudly, brightly.

Beaubien recently received the inaugural SF Camerawork Exhibition Award for her proposal Matter in the Hothouse. This award recognizes a project proposal featuring exceptional creative photographic work, and will support those efforts with an exhibition grant in the amount of $5,000. She will be opening an exhibition with SF Camerawork in the near future. An interview with the artist follows.

Aimée Beaubien is an artist living and working in Chicago. Beaubien reorganizes photographic experience while exploring networks of meaning and association between the real and the ideal in cut-up collages, artists’ books and immersive installations. A photographed plant, interlaced vine, woven topography merge into fields of color and pattern and back again expanding the ever more complicated sensations of reading a photograph and experiencing nature. Beaubien’s work has been included in national and international exhibitions including Demo Projects, Springfield, IL; Gallery UNO Projektraum, Berlin, Germany; Houston Center for Photography, Houston, TX; Marvelli Gallery, New York, NY; The Pitch Project, Milwaukee, WI; Virus Art Gallery, Rome, Italy. Her work is held in the permanent collections of Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL; Joan Flasch Artists’ Book Collection, Chicago, IL; Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, IL; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY. Aimée Beaubien is an Associate Professor of Photography at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, IL where she has taught since 1997. IG @aimeebeaubien

©Aimée Beaubien, Garden Flowers in Color, 2020 cut-up photographs, paracord, PLA filament, polymer chains, porcelain chains, miniature clothespins, vintage garden books, PLA filament leaf drawings, gilded leaves, dried flowers Artists Run Chicago 2.0, Hyde Park Art Center, Chicago, IL

The imaginative expanse of the home, museum and garden holds me. In it, lines blur between public and private, institutional and domestic, labor and leisure, propagation and contemplation. Wild, fast growing vines slink through the yard, climb up and around our house. Inside my home studio, plants mingle with huge tangles of cut and woven photographs that dangle down from the ceiling. I photograph the ever-changing conditions in my studio as plants dry and projects grow.

With my camera, I move through different types of collections reflecting on our attachments to objects, focusing on the complex tethers between an artist’s work and the things they collect. I spent one year photographing in the home museum known as the Roger Brown Study Collection, capturing my own impressions of the articles that surrounded this celebrated Chicago painter during his lifetime. Brown’s multilayered assemblages drawn through his domestic spaces felt like collages activated as my body drifted throughout his home. After learning that Roger Brown cultivated fifty different varieties of roses in one of his gardens, I began to think more deeply about how the idiosyncratic nature of our personal collections extends into the compositions of the gardens we construct.

©Aimée Beaubien, Hothouse Picture-Cyclopedia, 2019 cut-up photographs, paracord, polymer chains, porcelain chains, grow lights on fabric cord, miniature clothespins, vintage garden books, PLA filament leaf drawings, gilded leaves, dried lemons, dried plants dimensions variable New Formations, Catherine Edelman Gallery, Chicago, IL

Archeologists have been unearthing and restoring Emily Dickinson’s garden in an effort to better understand her personal world and source of creativity. Dickinson kept collections of letters addressed to her close at hand to record textual fragments running every which way along the flaps and folds of her envelope poems in flashes of impulse. The spliced open and folded, the domestic and the collected, the intersecting and multidirectional structure: these too are the substance of my photographic cut-ups that take form in artists’ books, collages, sculptures and installations. My own notational flashes exist as photographs and from my prints I create ephemeral paper structures that accommodate, attach, climb, trail, cling, spread, creep and rearrange within each new exhibition environment: loudly, brightly.

Throughout the seasons and over her lifetime, my great-grandmother attentively photographed what grew around her. Extending this fertile lineage, I photograph in my tiny Chicago garden, my mother’s lush Florida garden and the many gardens in-between. I translate my responses into an array of different representations of size and push color to its limits, cutting my printed notations apart to completely reorganize photographic material and experience. The effects of time on the color of my great-grandmother’s snapshots – some screaming in degrees of hot pinks, others soaked in glowing oranges – hover in my imagination as I weave together my own saturated prints.

©Aimée Beaubien, Hothouse Picture-Cyclopedia, 2019 cut-up photographs, paracord, polymer chains, porcelain chains, grow lights on fabric cord, miniature clothespins, vintage garden books, PLA filament leaf drawings, gilded leaves, dried lemons, dried plants dimensions variable New Formations, Catherine Edelman Gallery, Chicago, IL

My work draws from an environment of hyperstimulation, compulsion and interruption; comparing the disjointed experience of attention and distraction to the sharp recontextualization of collage. I document my own personal entanglements with domestic spaces, institutions, archives and narratives suggested by the life and histories of things. These webs of connections are rewoven into vibrant configurations, tethered within installations that become physical presences moving in and through exhibition spaces. Expanded ranges of time are illuminated in environments folding around and stretching into the peripheries of visual and architectural space. My works are bright yet fragile assertions of personal and art historical trajectories at the margins of the archive. – Aimée Beaubien

©Aimée Beaubien, Tangled Sensations, 2018 cut-up photographs, printed satin, grow lights on fabric cord, hammock chair swings, paracord, carabiners, miniature clothespins, dried lemons, dried plants dimensions variable Truth Claim, Carrie Secrist Gallery, Chicago, IL

Take us back to the beginning. How did you come to photography and at what point did you begin to intervene as an artist, following a less traditional path?

Making has always been a form of thinking and processing information for me.

“TWO OCTOPUSES GOT MARRIED AND WALKED DOWN THE AISLE ARM IN ARM IN ARM IN ARM IN ARM IN ARM IN ARM IN ARM IN ARM IN ARM IN ARM IN ARM IN ARM IN ARM IN ARM IN ARM…” is the very first thing I remember igniting my imagination. The enchanting illustrations are easy to recall, with text crawling all over the page like concrete poetry in this dazzling children’s book by Remy Charlip titled Arm in Arm. Books have been a lifelong source of inspiration for me. I grew up obsessed with a particular collection of books long before my studio filled to the brim with photobooks, artists’ books and zines. The bottom shelf of some place that we lived in the 1970’s held an engrossing Time-Life book series called The Family Creative Workshop. My mother dreaded the big mess brewing whenever she caught me crouched in the corner paging through the possibilities of what to make.

About one week of each summer break throughout elementary school involved making things with my great-grandmother. I loved watching her look down into the ground glass of her Argus Seventy-five which was always within her reach and a huge part of her daily routine. She photographed the plants growing around her every day, throughout the seasons and over her lifetime. Having lived through the Great Depression she repurposed everything. We cut up her wedding dress with its fancy petticoat in order to sew a new set of clothes for her china dolls. Together we stuffed a special pillow for her cat with cat hair that she had carefully collected over the year. She cut out a photograph of her face to attach to a body modeling control top pantyhose and taped that collage to her refrigerator in an effort to control her appetite. I closely studied her magical collage gestures before I even understood what it was that she was doing. Now I have a timeline of photographic processes over my great-grandmother’s lifetime. I regularly dip into trunks filled with her pictures and her photocollage hangs in my studio with me as I rework photographic information.

When I first began seriously studying photography we were required to have two finished and matted gelatin silver prints in class each Friday for critique. This schedule was a formative introduction to what the life of an artist could be. I presented at least one photo-collage for every crit and that continued throughout all of my photography classes and even into grad school when I would piece together larger-than life photographic bodies to make two giant silver gelatin mural print photo-collages weekly.

My earliest photographic impulse came of a desire to dissect my photographs to better understand to how pictures are constructed. Even though my cut-up efforts regularly elicited confusing responses I somehow managed to follow my own interests relatively undeterred. Maybe this is because I have always regarded photographs as material to manipulate having grown up watching my great-grandmother write captions on all sides of her drugstore prints while also cutting up her photographic records to reorganize her personal information. Or it could be that my own curiosities about the many different ways that all things photographic circulate through the world is a more powerful magnet than the criticism. On occasion it helps to remind myself that everything I make is layered and complicated and not for everybody but it remains true to me.

©Aimée Beaubien, Dangling Cluster, 2020 cut-up photographs, paracord, miniature clothespins, PLA filament leaf drawings, gilded leaves, branch dimensions variable Kismet, Monaco Gallery, Saint Louis, MO

What sparked the idea of making your photographs sculptural?

I spent decades puzzling together a complex of picture relationships, weaving layers of pictured subjects over and under but realized through conversation that other people did not see what I saw. And even worse, when my cut-up photocollages are documented or framed behind glass everything is utterly compressed into a single flattened thing. This disappointment encouraged a stronger urge to figure out different ways to represent my lived experiences with photographic information. A gradual transition began by pushing my 2-d collages off of the wall just enough and directing artificial light sources to create dramatic shadows that underscored their object-ness. Then I moved on to figuring out how to cut and bend photographs more aggressively into sculptural forms. The first big step was cutting up photographs that I had taken of baskets in order to weave them back into basket forms.

Shortly thereafter I was completely entranced by a collection of hinged sheet metal sculptures from the 1960’s created by Lygia Clark’s that she called ‘Bichos’ (critters). In Clark’s 2014 MOMA retrospective there was an invitation to handle replicas of these captivating creatures in order to navigate your own experience of folding and unfolding her sculptures. The hinges implied movement and change with no clearly defined front and back, inside and outside, up and down. These sculptures embodied all of the gestures that I had been trying in vain to express in my 2-d photo collages. I returned to Chicago emboldened to make even bigger moves in photo-sculpture and very quickly threw myself into constructing immersive environments comprised of entangled photographic material. At about the same time I noticed a vine that had started winding around our ancient garage that made the wooden structure appear sturdier as it grew and thickened. Soon I was paying closer attention to stray morning glories as they strangled other plants in our tiny garden. Now I am completely mesmerized by the movement of vines, their steadfast embrace of everything that they encounter and have modeled forms of creating after the various ways that vines touch their surroundings.

©Aimée Beaubien, Plumb and Twining, 2020 cut-up photographs, paracord, miniature clothespins, PLA filament leaf drawings, gilded leaves, branch dimensions variable Kismet, Monaco Gallery, Saint Louis, MO

What are the challenges of working with such complex installations?

Tight time constraints for install is hands down my biggest challenge. Some galleries regularly hang straightforward shows in one day. During the pandemic I had one day to install something and carefully choreographed everything beforehand in order to complete my fastest installation ever. It felt like I was on game show without the balloons or celebratory streamers at the finish line. In my studio I rehearse parts of an installation from start to finish in order to calculate how long the whole install might take and to determine what materials are needed. I take notes, list what must travel out of my studio with me, photograph important details before taking anything apart to finally pack everything that is needed to reassemble my work on location.

Chicago is filled with awesome galleries and killer alternative spaces. Whenever there is a chance to exhibit close to home I try something new to me knowing that my studio and supplies are easy to access nearby. Local exhibitions are also really important experiences that go a long way in preparation for out-of-town opportunities. Problem-solving is a challenge that I really enjoy. I ask myself a series of questions like what could a solo exhibition overseas be if everything had to fit inside of a duffle bag for transport? I have encountered several exhibition environments that did not allow drilling into the ceiling so sometimes the first moments of install require careful examination of alternative scenarios that do not detract from the impact of my overall plan.

My biggest disappointments have been when I did not spend more time documenting the install process from start to finish. I get hyper focused on what I am doing and often forget to take breaks to photograph. While trying to photograph my work I have found that the documentation often swallows itself whole and, in the process, generates new images and ideas to work from. I continue to experiment with different ways to document my work and bang up against the dizzying condition of trying to encompass all of the unruly parts. Because my immersive environments tend to have a maximalist aesthetic people often ask when I know my installation is done. For me it feels finished when I start removing more elements than I am adding. More is more and if I can afford the extravagance of bringing a surplus of material I always do because inevitably unanticipated alternatives will be revealed while spending extended periods of time working in an unfamiliar location.

©Aimée Beaubien, Hothouse Cuttings, 2018 cut-up photographs, printed satin, grow lights on fabric cord, hammock chair swings, paracord, carabiners, miniature clothespins, dried lemons, dried plants dimensions variable Birds and Bees, Lubeznik Center for the Arts, Michigan City, IN

Do you create work for a particular space?

Multiple things happen in my studio simultaneously. I am always making something, testing materials, repurposing works, documenting various stages of development, researching and planning. When I am preparing for an installation I explore many different ways that my work could occupy that particular space. The thrilling aspect of building installations for me is that each exhibition opportunity never feels the same nor does the work appear exactly the same from one situation to the next. In this way the work is very alive to me. It moves, transforms and new elements are always being introduced into each new installation. I am driven to experiment while taking into consideration how to react to the unique characteristics of each exhibition environment.

Last summer I was able to work in a local gallery for an entire month so there was even enough time to print new works in my home studio during the evenings that could be incorporated into the overall installation during the days. Since this opportunity happened during the pandemic I knew very few people would experience the installation in-person so I decided to purposely avoid locking down plans ahead of time in favor of exploring what could happen through improvisation. I had just pulled down 30 feet of continuous vine from our garage and knew that it would be the starting point but I did not allow myself to think any further until I wrestled that giant vine through the space. The overall experience was exhilarating, primarily because I had plenty of time to take anything apart that was not working. If the install time had been shorter it would have been far too stressful to risk showing up without a master plan.

©Aimée Beaubien, rooted-looping-scrambling-rambling-tangling-twining-tendrils, 2020 cut-up photographs, paracord, polymer chains, porcelain chains, grow lights on fabric cord, miniature clothespins, vintage garden books, PLA filament leaf drawings, gilded leaves, dried lemons, dried plants, branches dimensions variable Open Studio: rooted-looping-scrambling-rambling-tangling-twining-tendrils, 062 Gallery, Chicago, IL

What is your dream venue to exhibit work?

It is useful to ask myself this terrific question regularly as an open-ended prompt. While walking through any exhibition environment I imagine how my work could inhabit the space and respond to the specific characteristics of each different place. I dream about working in a largescale site over a longer period of time. My fantasies are vast and include, but are not limited to: a sprawling warehouse environment, an elaborately decorative palazzo in Venice (really anywhere – encountering contemporary works inside ornate interior architecture is riveting), a home museum or exhibition space in a home, all project spaces (especially those that are unconventional), a moving vessel like a ship, just about any artist run exhibition arena, a conservatory, outdoors in a town square, garden, park or arboretum… what about a whole island if I am really dreaming? Gosh, I guess I am really open to considering just about anything. In the meantime, I continue to lean into daydreams with fairy tale budgets.

©Aimée Beaubien, Twist Affix, 2017 cut-up photographs, grow lights on fabric cord, paracord, carabiners, miniature clothespins, dried lemons, dried plants, oscillating fan dimensions variable Twist Affix, RAC Freeark Gallery, Riverside, IL

Do you think you will ever go back to the framed image (if you ever worked that way)?

Right now, I am drawn to experiencing photographic material expressed in various states of potential: movement, flux, transformation, fragility, weight, growth. Some of my works that have been packaged in frames end up feeling utterly past tense to me these days. It seems as if the urgency of that particular impulse to make something has been squashed with all of the lifeforce sucked out of it. I am far too embarrassed to admit how many framed pieces are currently stored in our basement but I am very fond of my framed gelatin silver print collages that hang in my bedroom. Occasionally I think about switching out my work to replace it with that of friends because I so want to live with their awesome artwork. That has yet to happen since I have a hard time sacrificing studio time. Would I ever frame anything again? Yes, and I do but only when I know it is best suited for the final destination.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Carolyn Monastra: Divergence of BirdsFebruary 2nd, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Yi Wan Gyo: Nirvana-Beyond DarkJanuary 13th, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Han ChungShik: GoyoJanuary 12th, 2026