Focus on Installation: Melanie Walker

When I think of the work and installations of artist Melanie Walker, I think of magic and childhood, of play and memory, and most importantly, a legacy of incredible art making that transforms the medium in innovative ways. As a visually impaired artist, she lives in a space between sight and blindness and her work “invites others to experience a different world where the very nature of what is real can be questioned.” Walker is a storyteller of the best kind, leading us into worlds we might encounter in our dreams. Her Sheltering Sky installation with the cloud circles of confusion at Walker Fine Art in Denver is on exhibition until May 8th. An interview with Walker follows.

Melanie Walker has been a practicing artist for over 50 years. Her expertise is in the area of alternative photographic processes, digital and mixed media as well as large scale immersive photographic installations and public art. She attended San Francisco State University for a BA and Florida State University for an MFA. She has received a number of awards including an NEA Visual Arts Fellowship, Colorado Council on the Arts Fellowship, Polaroid Materials Grants and an Aaron Siskind Award. She currently teaches in the Media Arts Area at the University of Colorado Boulder and her work is housed in collections nationally & internationally including CCP, LACMA and The Smithsonian. She is represented by Walker Fine Art, Denver, CO (no relation) & Tilt Gallery in Scottsdale, AZ.

My earliest memory is deeply etched in my being. I had just had eye surgery in an attempt to correct my wall-eyed birth defect. I was strapped in a hospital bed, alone, at 3 years of age, with an eye patch over one eye. Waking from surgery the first thing I saw was a chimpanzee wearing a band-leader’s uniform riding down the hall on a tricycle. This event has been instrumental in my approach to the world and how I make work.

I live with double vision being legally blind in one eye; the gift of being able to experience the world from multiple perspectives simultaneously. Due to my vision challenges I have a need to make work that is dimensional, tactile, haptic, multi-sensory. Living with both sight and blindness, I seek to be a bridge to empathy.

Take us back to the beginning. How did you come to photography and at what point did you begin to intervene as an artist, following a less traditional path?

In some ways I think it started a couple of generations before I was born.

My grandfather, with whom I share a birthday, helped design the first sound studios in Hollywood. He died from overwork and emotional exhaustion when my father was 14, but before he died, he set up a darkroom in the family bathroom and introduced my father to the magic of photography and a passion for experimenting with light, film and chemicals.

When I was born, my father, Todd Walker, was just getting established in the LA photographic world. By the time I was 7, he was doing major Chevrolet advertising campaigns and I was frequently the daughter in these fake family scenarios designed to sell the myth of the American Dream. While he was doing the commercial work to support the family, he was also experimenting after hours with historical processes and storing the work in a drawer. I grew up with a keen awareness that questioned the veracity of images. There was no market for experimental or art photography at that time but there were always adults at our house who were impassioned with the possibilities contained within this plastic medium called photography. Wynn Bullock was a frequent visitor who my father had met during his summer class at Art Center in 1939. My father was selected by the LA ASMP to visit Edward Weston when I was about 5 to select some prints for purchase to help cover Weston’s medical bills. Around that same time, Robert Frank and his family came to dinner. We went to Edmund Teske’s bizarre auctions along with everyone interested in photographic art in LA. Robert Heinecken, Robert Fichter, Darryl Curran and many others were frequent visitors sharing work and ideas and there were many photo excursions. When I was 14 my father had a one person exhibition of his personal photographic artwork at the Museum of Science and Industry (now the California Science Center). All of these adults had a big impact on my life. How could I ever think about doing anything else?

I think my first print was a paper negative that I made of our cat. I don’t think I ever had a traditional idea of what photography was supposed to be. It was about questioning, pushing boundaries, dancing at the edges of photography, questioning the idea of truth behind photographic illusions and unmasking those illusions.

Reality seemed like a spectacle. Photography seemed like a playground rife with possibilities.

What sparked the idea of making your photographs sculptural?

I think the immersive nature of my photographic installations derives directly from the environment I grew up in. Every inch of the house was covered with pictures. The pictures were always in relation to each other like a curated exhibition. The conversations at dinner were always philosophical and revolved around ideas connected with images. What was a photograph? What was photographable? Did a photograph have to be 2 dimensional? Et Cetera…

Another big factor is that I was born legally blind in my left eye and have experienced uncorrectable double vision all my life. I think because of my visual challenges, I felt a need for haptic engagement along with the visual in my work. I really like working with transparent materials so that as a person walks through an installation they see through the images to see multiple layers of photographic information like layers of memory and time occurring all at the same moment. When possible I like to introduce sound compositions I have created through ambient recordings at a very quiet level. I love whispering. Everyone wants in on secrets so when there is whispering, people pay attention because they want to know the secrets.

My mother was an amazing seamstress (along with being my father’s assistant) and my father’s world was photography. I think I drew from both of their influences combining photography with fabric. (I have also learned recently that my family name Walker, derives from Gaelic and means weaver of the cloth so maybe it’s genetic…) In grad school at FSU all of my research and thesis work was focused on soft sculpture photography and was highly influenced by women photo pioneers like Betty Hahn, Ellen Brooks and Bea Nettles.

What are the challenges of working with off-the-wall installations?

The main challenge I have found working with immersive installation is finding spaces, funding and storage. My first installation was in 1974 for my thesis exhibition. It was some 12 years later when I had the opportunity to do more installation work at Alfred University when I taught there. I made sound tracks, optical toys, juxtaposed photographs I made alongside the objects photographed. I made miniature viewing boxes and cyanotype quilts that the local Amish community quilted for me. (It was an experiment to learn how much the Amish knew about photographs since they aren’t allowed in the Amish belief system.) Everything was set off by motion sensors and hidden switches. Following my father’s example I have taught myself how to do the things I couldn’t afford to hire someone to build for me. I learned minimal electronics, sound editing for my ambient recordings, gearing down motors and so many other funny skills. Over the years I have figured out ways to minimize my storages challenges by learning how to make things that are lightweight, portable and can easily be stored in small spaces.

With the vision challenges I have faced, I can close one eye and experience the world as a blind person. With this double vision, I have long felt that I could potentially be a bridge between the sighted and the blind. This is a big part of the drive behind much of my installation work, inviting others to experience a different world where the very nature of what is real can be questioned. Time spent in the back lots of Hollywood have influenced this practice along with my love for the pre-history of photography and the dioramas that Daguerre made in the 1830’s. (The diorama was a 19th century light based medium that involved two large scale paintings lit from both front and back inside a darkened, rotating auditorium. Incorporating both opaque and translucent painting techniques, natural light was manipulated through a series of shutters and screens, creating a live, immersive spectacle. This real time performance using light manipulation is considered to be a significant part of the pre-history of cinema and photography along with the camera obscura.)

Do you create work for a particular space?

I intentionally make my work that is malleable so it can be shown in a variety of ways and is not necessarily site specific. In the 90’s I started collaborating on public art with my artist/partner, George Peters, who is a kite maker and a sculptor. (https://www.airworks-studio.com) Our public art is site specific but my installations for exhibitions are not. I like to reuse installation components in multiple venues to explore different configurations almost as a way to reference memory. Is memory based on a recollection of an experience or the last time we remembered that experience? Audiences always have different viewers and everyone experiences things in their own unique way. Additionally, most of the concerns behind my work are driven by environmental anxiety so I don’t like to generate waste.

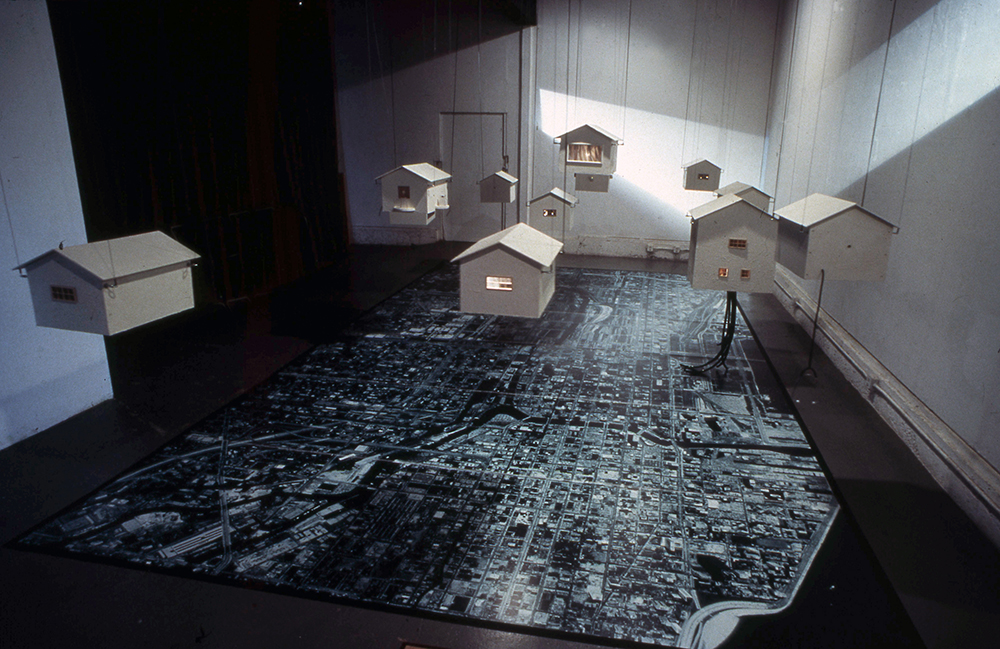

What is your dream venue to exhibit work?

My dream installation would be to bring previous installation elements along with new components together into an immersive transitional environment like walking through a life size narrative without a specific story. Viewers would enter beneath the sheltering sky and walk through the ghost forest and the canopy of leaves of absence overhead. They would walk through the floating city with miniature tableaus contained within suspended houses and down the center of the street of silk city encountering Househead puppets all along the way whose strings they could pull to activate a range of motorized optical toys and quiet sound compositions that would almost seem as though they were imagined, like whispers. The final experience of the installation would be an encounter with a sleeping Househead where viewers could choose to sit in the chair next and eavesdrop on the dreams of the Househead. As they exited , they would be invited to fly one of the Househead kites and experience the wind. My favorite part of making installations is to hear stories from the viewers of what they experience. Stories. We are all made up of stories.

Do you think you will ever go back to the framed image (if you ever worked that way)?

I never abandoned the print, that is where everything begins. I used to try to get photography out of the rectangle, out of the frame, but then I expanded my idea of what the frame could be. Framing historically was a way to convey ownership and when a piece of artwork traded hands, it was reframed. Being raised by my artist father who taught himself how to run a press because he believed in the democratization of art at a time before there was a market for photographs, I was always driven to push the boundaries rather than make work for sale.

I am drowning in prints and weaving a context for the photographs has been a big part of my practice. I guess it all started with dreaming about other ways to experience photographic realities. In my installations I seek a space for stories and allegory; space between waking and sleep where reality is questioned. A space before words. A space where there is a suspension of disbelief. A transitional world that invites viewers to move between this world and another possibility.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026