Film Photo Visionary Project Award: Graham Dickie

Photographer Graham Dickie’s poignant project, How Life Is, recently garnered the Spring 2021 Film Photo Visionary Project Award. With the support of the Film Photo Award, Graham will continue photographing rap and daily life in Louisiana, with particular attention to the countryside surrounding Baton Rouge. The resulting project will approach the state’s street rap scene with a grassroots, humanistic perspective, focusing on young aspiring artists – how their music, with its deeply autobiographical underpinnings, connects to their communities and speaks to America’s broader reckoning over racial injustice.

The Film Photo Award is open to all emerging, established, and student photographers worldwide. Each award period provides three distinct grants of Kodak Professional Film and complimentary film processing by Griffin Editions to photographers who demonstrate a serious commitment to the field and are motivated to continue the development of still, film-based photography in the 21st century. The Spring 2021 grants were juried by Paddy Johnson of Art F City, previous Film Photo Award recipient Jon Henry, and Film Photo Award founder Eliot Dudik. IG @filmphotoaward

Graham Dickie (b. 1995) is a photographer from Austin, Texas, USA currently based between Austin and rural Southeast Louisiana (Clinton – population 1,653), where he’s pursuing independent documentary projects while working closely with the local hip-hop community.

Graham graduated from the University of Texas at Austin in 2017 with highest honors in the Plan II honors program and journalism. While a student, he embedded with a small group of deaf journalists in Maputo, Mozambique; worked for a film studio in Austin on a documentary about the legendary newspaperman Gene Roberts; and filed radio reports from the National Public Radio member station in Marfa, Texas. He completed his thesis – on small-town Southern rap – under the supervision of photographer Eli Reed.

After graduation from UT, Graham followed the ancient Silk Road from Kazakhstan to Beijing, living there for nine months and working at Three Shadows Photography Art Centre (三影堂摄影艺术中心), the leading space for photography in the country. From China he went to Scandinavia, where apprenticed with the Magnum photographer Jacob Aue Sobol for much of 2018 while living on a remote stretch of Danish coastline.

From 2020 into 2021, Graham served as the annual photography intern at National Geographic. In 2019, he was named College Photographer of the Year by the CPOY competition for a portfolio of his work from the past year. He attended the 30th Eddie Adams Workshop in 2017, and in 2018 his work in rural Louisiana received first prize in the Alexia Foundation’s student grant competition, providing for a semester-long fellowship at Syracuse University.

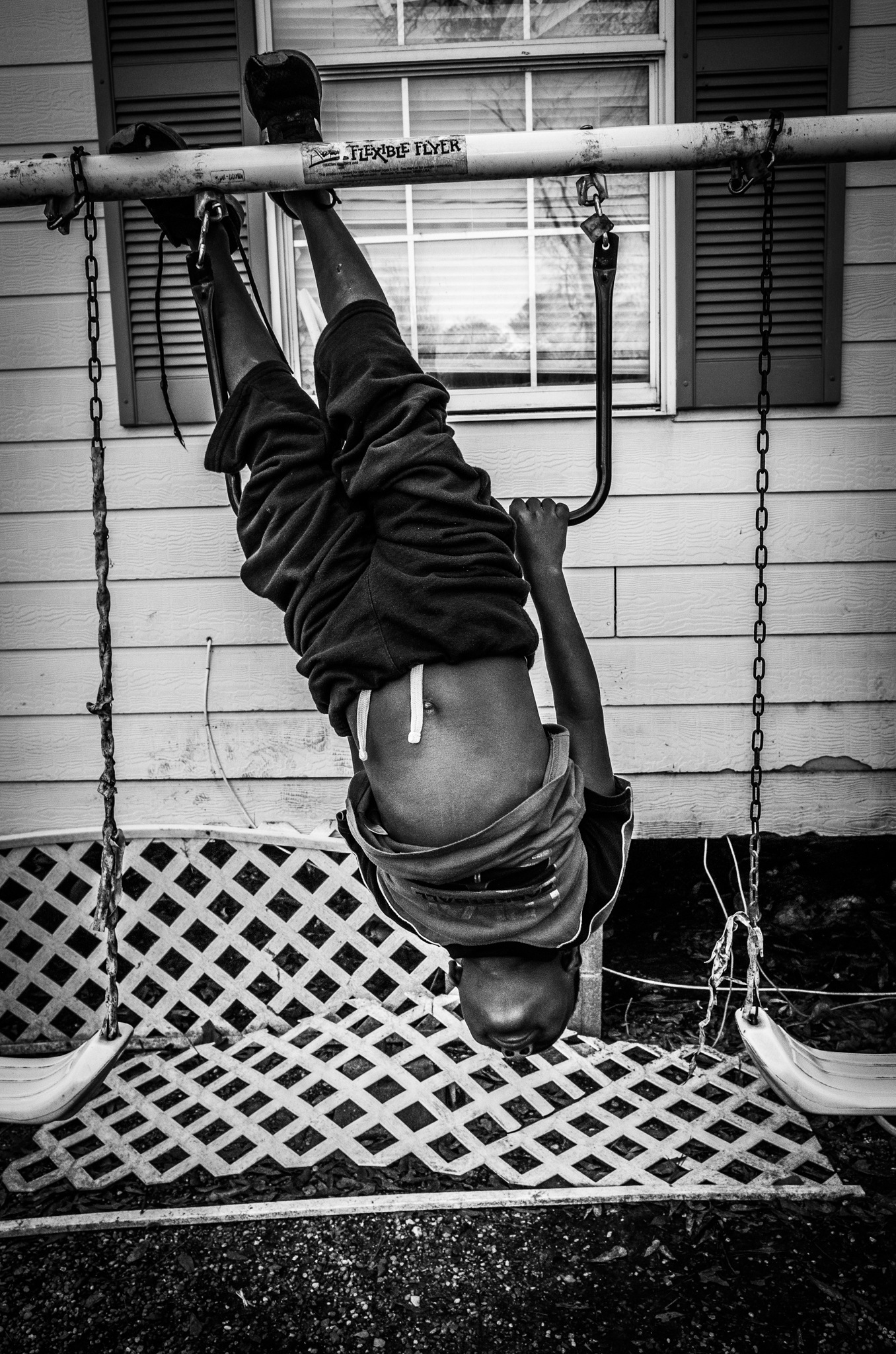

How Life Is

Baton Rouge, Louisiana and its surrounding countryside are home to hundreds of young people making rap music in order to express their reality in today’s South. The vicious cycle of rural poverty, the police shootings that have killed family members, the joy and faith that nevertheless persist inside them – these are some of the real subjects driving these artists’ deeply autobiographical music.

The last few months have seen a lot of conversation about how America can understand systemic racism and its broken justice system. Understandably, many have pointed to resources coming from intellectual circles, but with my photos, I want to help make an argument for the immense value of the folk art being recorded by young Black people in a place like Southeast Louisiana, who – living in the Deep South especially – bear an extremely heavy burden in terms of historical racism and oppression.

Excluded by dominant social institutions for generations, young Black Southerners have forged their own avenues for expression, and yet I feel like their voices are still ignored by the quote-unquote cultural mainstream when, in fact, they have much to teach us. The street rap being made by young people in Southeast Louisiana – and daily life there – is challenging but raw and vital, of absolute relevance to our current reckoning. The melodies and words emerge directly from their community and sensitivity to daily life, and the songs present the voices of young Black Southerners on their own terms.

Louisiana street rap has enormous regional popularity and cultural impact, and recently achieved a high-water mark: in 2020, NBA Youngboy – a 21-year-old who grew up in the shadow of the colossal ExxonMobil chemical plant in North Baton Rouge – became one of very few solo artists in the world to have had three separate albums top the Billboard 200 within a year. This can be explained in part by the intimate bond he’s forged with listeners coming from backgrounds like his, making music that’s diaristic and vulnerable, swinging between exultation and heartbreak. (Youngboy’s album AI YoungBoy 2, from 2019, is a great introduction to Louisiana rap, emotionally poignant and technically superb.)

I want to show what life is like for these young artists in Baton Rouge and its hinterlands (which includes small towns like Zachary, Jackson, St. Francisville, Clinton, and Slaughter) – how their lives connect to their art and speak to these broader social issues in a time of necessary turmoil and soul-searching. I’ve been coming to Louisiana for close to five years now. It feels like home, and many of the friends I’ve made in the course of photographing there are dear to me. I’ve watched them grow as people and artists and in many ways I feel as if I’ve found my creative community here – in underground Louisiana street rap – rather than in “photography” so to speak.

I believe what these young people are making is folk art in the finest sense, something completely sui generis that speaks organically to their own lives and the people closest to them. My photography there originates from that respect and genuine feelings for what they’re doing, and visualizes some of what I hear in the music. Their approach is something we could all learn from as humans and artists. With almost no institutional support or resources, they find a way to make music and talk about what’s closest to them. – Graham Dickie

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Yorgos Efthymiadis: The James and Audrey Foster Prize 2025 WinnerJanuary 2nd, 2026

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)October 1st, 2025