Raymond Thompson: In/Visible

With my work, I have sought to challenge America’s visual archive that has left out, ignored, disregarded, downplayed and distorted the role of black people in American life. I have also sought to highlight the photographic medium’s role in defining the American racial caste system. Finally, I have begun to explore the visual edges of my personal history, which due to an absence of material, I have had to create my own speculative narratives.

I thought I’d come full circle and begin this week of celebrating the 2021 Student Prize Winners with a nod to last year’s recipient of the the 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize, Raymond Thompson, Jr.. It has been a complete pleasure to get to know Thompson over these past twelve months and we wish him all the best as he moves on from his West Virginia home and West Virginia University, Morgantown to accept a position of Assistant Professor of Photojournalism at University of Texas, Austin. I always feel as if I learn more from the Student Prize winners than they learn from me and Thompson is no exception. He’s carried a lot on his shoulders–fatherhood and a job at the university all while completing his MFA in Photography. Today we celebrate his thesis project, In/Visible and wish him all the best in his upcoming endeavors. An interview with Thompson follows.

In/Visible features three series, the trauma of white light, Playing in the Dark, and a video piece, Let him in. The trauma of white light features five chlorophyll printed tobacco leaves that have been mounted in open black shadow boxes and hung on the wall. Pins have been placed around the edges of the leaf so as to not damage the fragile leaves. “There is no glass between the viewer and the leaf, which pushes the leaf forward and emphasizes it as a singular unique sculptural object. If a viewer gets close enough they may smell tobacco, enhancing the phenomenological aspects of the work. The physicality of the dried leaves makes a claim on reality by connecting the viewer to a moment of agricultural and cultural history. While researching the Library of Congress archive, I discovered images created by the Farm Security Administration (FSA) during the 1930s. A few of the FSA staff photographers — including Jack Delano and Dorothea Lange — had visited my grandfather’s region. These photographers depicted life on the plantations, including portraits of individual black subjects working in the fields. In particular, Lange’s work featuring black farmers working in tobacco fields resonated with me and my yearning to connect with the past.”

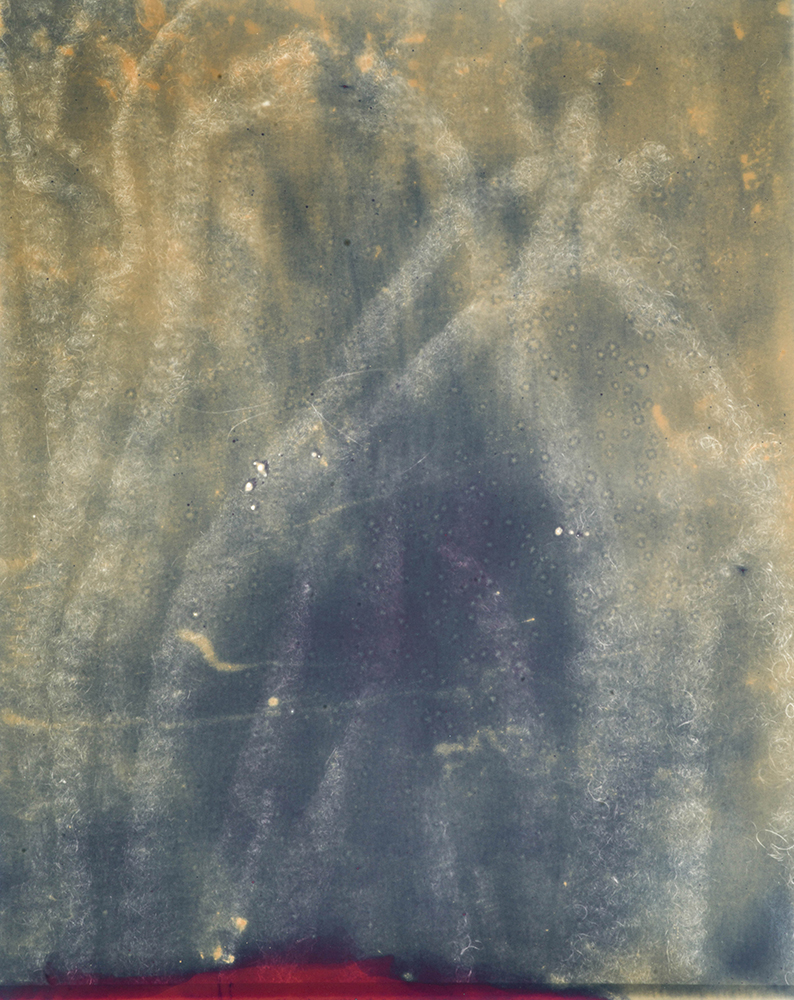

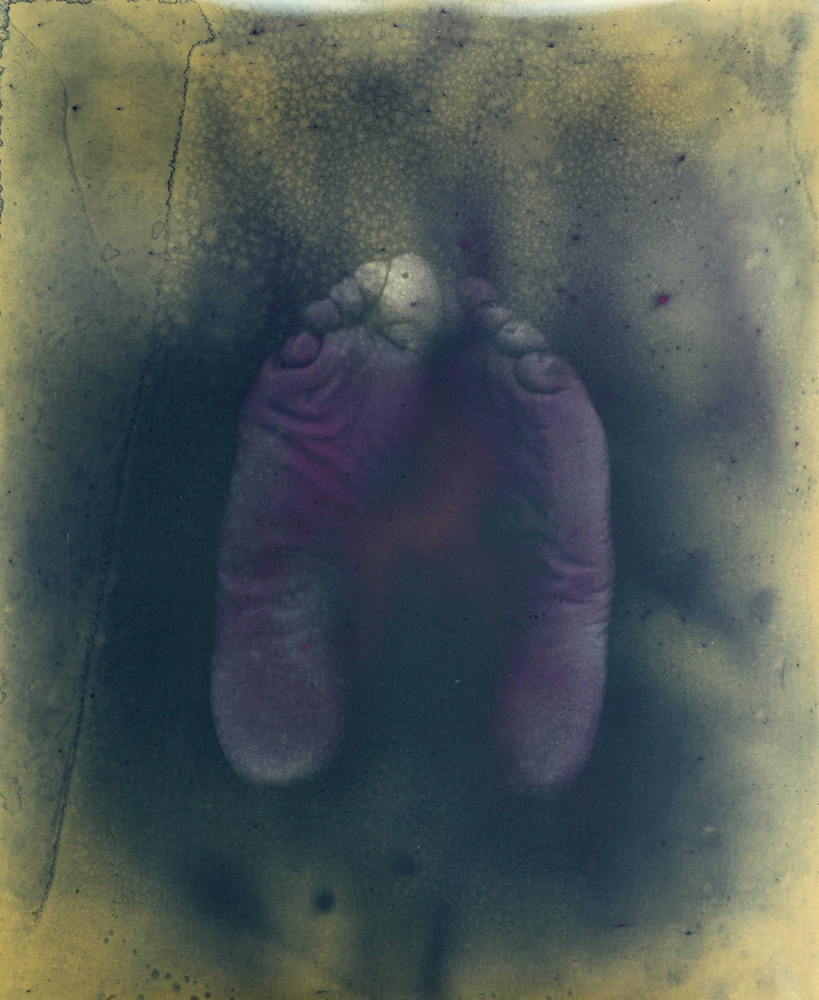

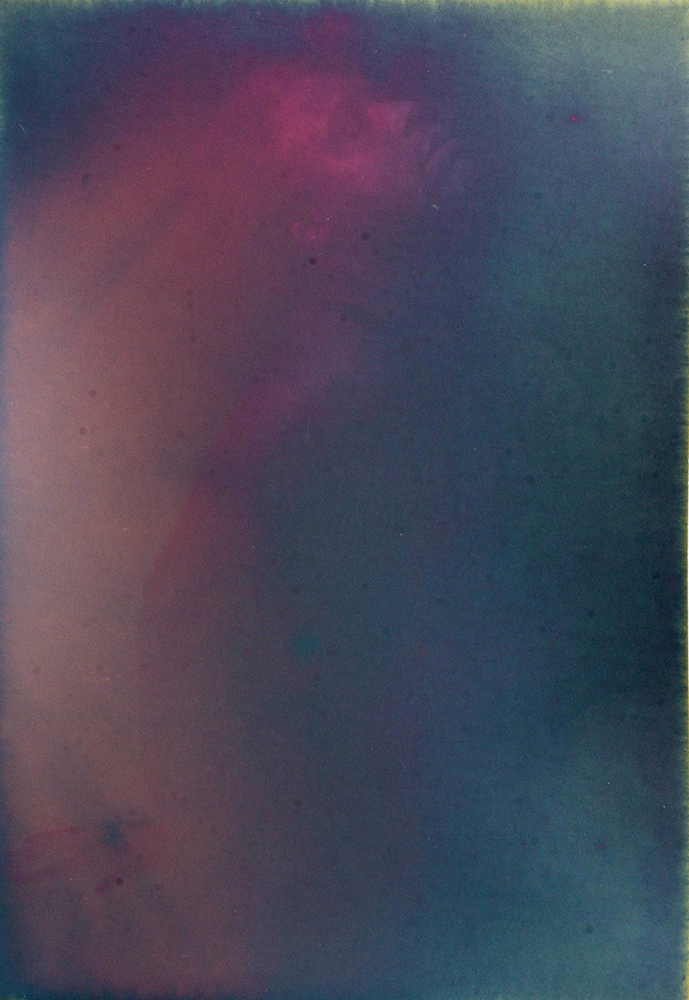

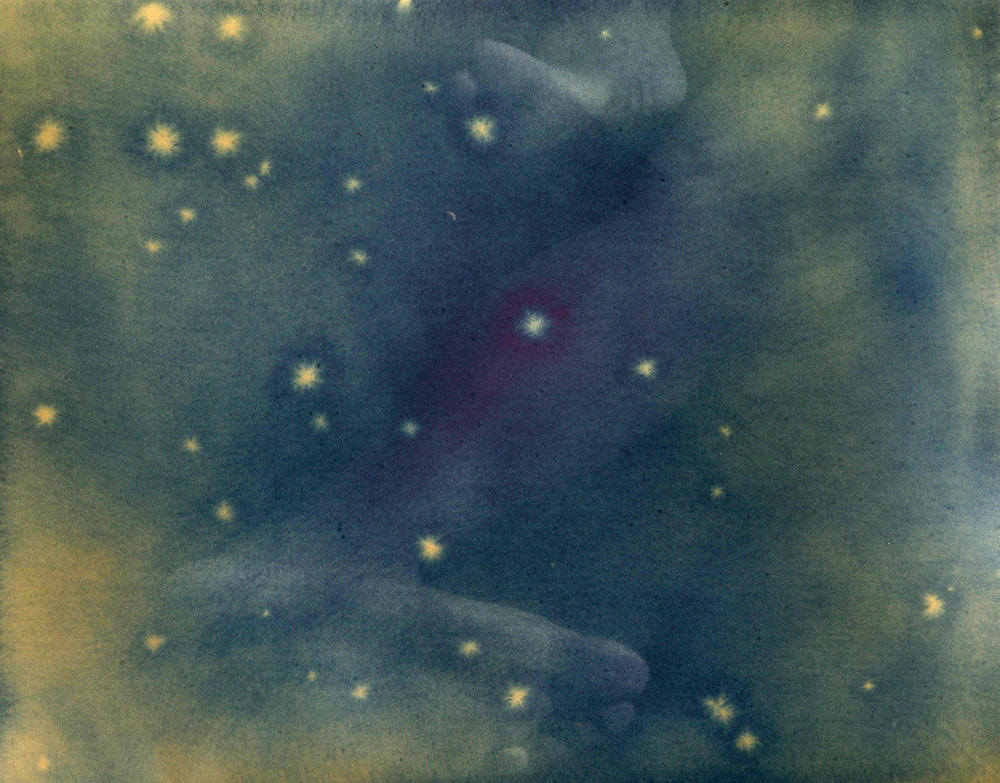

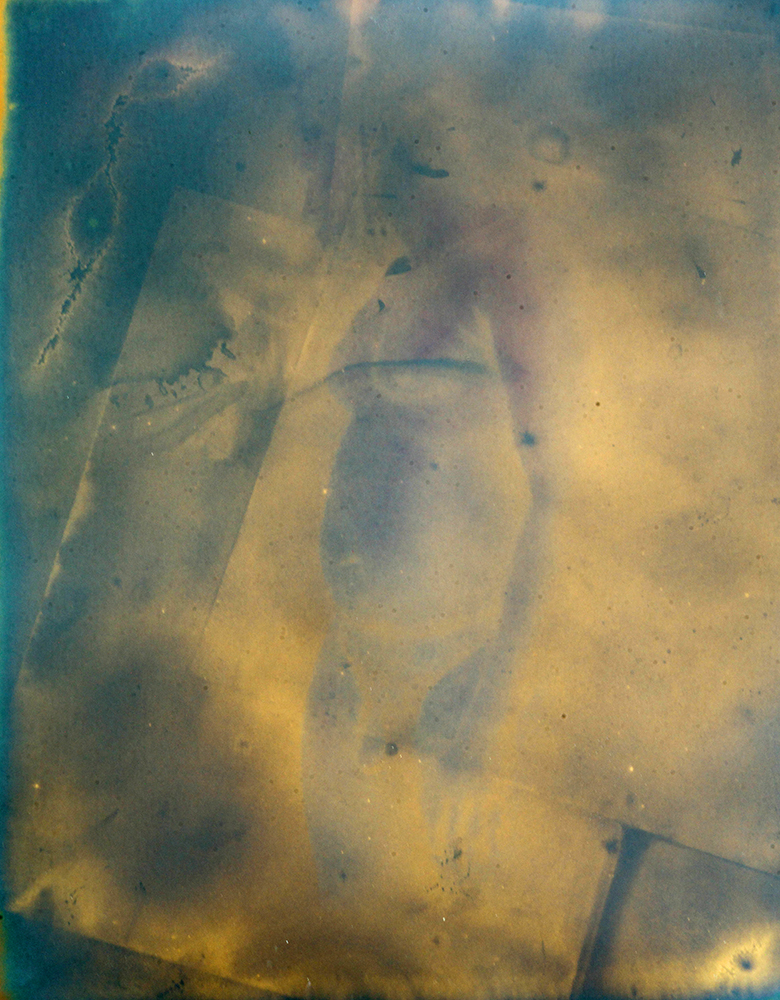

Playing in the Dark consists of 48 self-portraits lumen prints mounted organically on a wall. The series asks viewers to look deeper, by purposely deemphasizing my body with various levels of dark tones and colors. My body is not easily consumed in this work.

In/Visible

My MFA thesis and supporting exhibition focus on challenging the United States’ photographic archive that often left out African-American people. The work, through the use of appropriation and alternative photographic processes, disrupts America’s historical visual archive and notions that surround the white gaze. Through the unsettling of this visual space, new speculative narratives can be created to help imagine new futures. This work is the beginning of a process of mourning histories I have never known and reclaiming a place for myself and my family in the American landscape that is free of racial trauma. – Raymond Thompson, Jr.

You’ve had a lot of success this year. What have you learned from it?

I feel like the most important thing I learned was to be patient and build relationships. The Lenscratch Student Prize cracked opened a lot of doors. I did several online portfolio reviews and online studio visits. All these conversations and experiences were of value, even if they didn’t lead to an immediate show, print sale or book offer. Building these types of relationships takes time.

What brought you to working with historic archives rather than documenting the world in real time?

I spent the majority of my career as a photojournalist. In this space, real time was everything. Up until the start of graduate school the camera was an instrument grounded in the present. I was curious about how to use this tool in a more effective way to address the issue of the past and future. For me the black experience is so tied to the past that only focusing on the present seemed like overlooking something integral. At the same time, I want to leave critical space to imagine a black future. In looking to understand the past, I need some place to start. America’s visual archive seemed like the best starting point for my research.

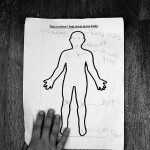

I began this journey close to my documentary roots with the project Imaging/Imagining, which looked at the symbol of the tree in black life in America. I created portraits of African Americans in the woods and paired them with quotes about how it felt to be in that space. I was deeply interested in how the black body was a part of and separate from the American landscape. I was struck by how racial groups were represented differently in America’s natural spaces. In Google searches it was easy to find quotidian images of white people enjoying the woods and other features of the American landscape. But, when I did the same search looking for the African American, I found a large percentage of lynching images. In the United States, the landscape is a political, rhetorical and historical space that over time has been used as a tool to boost the ideas that surround America’s ideology.

Can you talk about this discovery?

I began my Imaging/Imagining series by Googling “white people in trees.” This search term calls up photographs of tree climbers, hammocks and other romantic sublime images of non-minorities enjoying the outdoors. Then I Googled “black people in trees.” The first page of the search results show photographs of lynchings and other racially charged imagery. For me this discovery was chilling and created even more questions. One of those questions was a self reflection on my own experience with nature. I have always found nature to be suspect in some ways and usually tried to avoid rural spaces. I also knew that many of my peers felt similarly about these types of spaces. This led me to want to explore the relationship between African Americans and nature.

America’s social and cultural history of slavery, Jim Crow and mass incarceration has ignored and demonized black connection to the natural environment. The tree as a powerful cultural symbol in American memory has dual meaning. One meaning lies deep in the heart of American cultural identity, which is held in our vast preserved natural spaces. The other meaning lies at the heart of white supremacy and the historical memory of lynching.

These acts of racial terrorism not only served to reinforce white supremacy as the dominant social order in the Jim Crow South, but it did something more. For African Americans, these acts of violence became a warning that the woods, the trees, the rivers represented sites of potential racial violence.

At the time of the creation of this work, I believe in order for minorities to imagine the natural environment as a safe space they need to see images of other black and brown people safely navigating that space. I thought this body of work could be an invitation for healing the deep psychological scars inflicted by lynching.

Your thesis show is from 3 bodies of work–can you share the thinking behind the projects?

The In/Visible exhibition is an exploration of what it means to be seen and unseen at the same time. The exhibition is made up of three works, the trauma of white light, Playing in the Dark and Let Him In. I was really struck by Teju Cole’s essay, “A True Picture of Black Skin,” published in the book Black Futures. Cole makes an argument within the context of visual culture that minorities should have a right to control their own opacity.” I interpreted this to mean that visibility or a right to have people rendered clearly is not a natural right of the viewer. Photography has played a major role in defining the other in western culture — I wanted to push back against this a little bit.

What artists are currently inspiring you?

I have been looking at Laia Abril’s work a lot lately, and I continue to be inspired by Granville Carroll and Donnie Lee. I recently got a chance to see Dawoud Bey’s Night comes tenderly black and Kerry James Marshall’s Untitled (Gallery) at the Carnegie Museum of Art, and those works blow my mind.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Lorraine Turci: The Resilience of the CrowMarch 16th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Awards: Natalia Garbu: Moldova LookbookMarch 15th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Rayito Flores Pelcastre: Chirping of CricketsMarch 14th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Alena Grom: Stolen SpringMarch 13th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Louise Amelie: What Does Migration Mean for those who Stay BehindMarch 12th, 2024