Photographers on Photographers: Granville Carroll in Conversation with Lonnie Graham

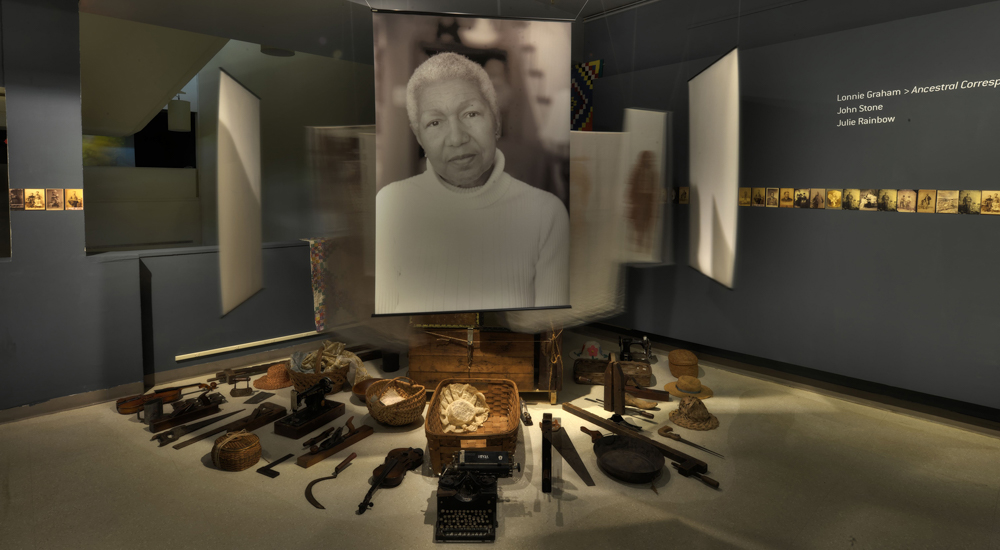

©Lonnie Graham, Living in a spirit house, Aunt Dora’s Room, Smithsonian Institution Washington DC.. This installation of artifacts moved from the artists home to occupy the space of national prominence was meant to help viewers access, understand and relate to artwork on multiple levels. This work assaults all the senses in an effort to help convey the common bond we all hold with our ancestors.

I met Lonnie Graham back in 2020 during the New England Portfolio Reviews (NEPR) facilitated by the Griffin Museum of Photography. Our conversation was quick, but in those 20 minutes we were able to uncover many connections. I selected Graham because of how our practices diverge and the similarities we share. Graham is a multidimensional artist who uses photography and installation to explore topics of humanity, community, and ancestry. His work directly involves national and international communities in the exchange of experiences, beliefs, rituals, and culture. I had a lot to think about after our initial interaction during NEPR and so I found this to be the perfect opportunity to dig into Graham’s artistic mind. I was particularly interested in the way he weaves together personal narratives with the larger context of history and world culture. Graham and I met via Zoom to discuss his work and artistic practice. Through an organic unfolding dialogue, we discussed topics related to humanity, community, culture, space/time, and art.

Lonnie Graham, a Pew Fellow and Professor at Pennsylvania State University. He is former director of Photography at Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, an urban arts organization dedicated to arts and education for at risk youth. There, Graham developed innovative pilot projects merging Arts and Academics, which were ultimately cited by, then, First Lady Hillary Clinton as a National Model for Arts Education. In 1996 Graham was commissioned to create the “African/American Garden Project.” which provided a physical and cultural exchange of disadvantaged urban single mothers in Pittsburgh, and farmers from Muguga, a small farming village in Kenya, to build a series of urban subsistence gardens.

In 2005, Professor Graham was cited as Artist of the Year in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and presented the Governor’s Award by Governor Edward Rendell. Professor Graham served as a panel member for the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts in Washington, DC. Lonnie Graham is the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts/Pew Charitable Trust Travel Grant for travel to Ghana and is a four time Pennsylvania Council for the Arts Fellowship recipient. His book “A Conversation with the World,” has been published by Datz press in Seoul, Korea. That project seeks to reveal our common humanity through interviews conducted by Professor Graham with individuals throughout the world. Other exhibitions include an exhibition of photographs at Goethe Institute, Accra Ghana; an exhibition of collaborative portraiture in Christchurch, New Zealand, a group of works at Kulttuurivoimala, Culture Silo, Meri-Toppila, Oulu, Finland, a full scale reproduction of one of the educational galleries in the Barnes Foundation shown at La Maison de Etat-Unis, Paris, France, an exhibition of larger than life photographs at the Toyota City Museum in Aichi, Japan as well as a room sized installation featured at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. Graham’s work can be found in the permanent collections of the Addison Gallery for American Art in Andover, MA and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in Philadelphia, PA

Follow Lonnie Graham on Instagram:@mrlonniegraham

©Lonnie Graham, This piece entitled resonant voices, installed at the African American Museum in Philadelphia is meant to symbolically illustrate the journey of African Americans from the southeast into major metropolitan areas of the United States during the turn of the century. At its core the installation is anchored by a pillar of trunks boxes and suitcases bound together with rope that was woven from sisal in East Africa. Translucent reproductions of ancestral photographs printed on silks surround the monolithic core. Portraits of the descendants of the African-American migrants are printed on paper and hang above an array of artifacts that also made the journey from the southern United States and to the north. These implements a representative of the skills black people brought with them. You will find typewriters, sewing machines, doctors kits, saws, hammers, musical instruments, writing implements. These black people brought with them the tools and implements to continue to build a nation, and they did. Surrounding the installation on the museum walls you’ll find a collection of images from the Eric and Paulette Robertson collection of African Americans photographed between 1860 and 1900, during the reconstruction era illustrating the fast and profound character of African-Americans during Reconstruction.

Granville Carroll: First, how are you doing today? How’s everything going?

Lonnie Graham: Oh just fine, thanks

GC: Beautiful. So let’s dive in! Photography is obviously one aspect of your practice, but you’ve created installations and used art as a means of cultural activism. I would like to know why you got into photography initially, and how you expanded your practice beyond the image and into installation and cultural activism.

LG: The installation of cultural activism is a direct reflection of what happens in the photographic process. It gives depth and dimension to the intent of the work. I think it would be fair to say that photographers deal primarily with some aspect of reality. It’s because of the immediacy of it. You immediately can express yourself on some level without having to interpret something or run and get a canvas or run over and get a pencil. Even with writers, they must go and transcribe their thoughts or ideas, which takes, in some cases, weeks or months or years. With photography, with a small machine or device, you could at the point of inspiration make an inconceivable document of your inspiration. If you saw something, if you’re reacting to something, you could immediately make a record of that thing, of the scene, of the area, the people or whatever it was without hesitation. Photography has a level of description and descriptive properties that’s beyond anything that we can conceive of. We start out with this kind of reality. We’re inspired by that thing. We use a device to document that experience in order to make a statement to communicate an idea. To help people understand we take those images and we sequence them. We present them in order to refine a level of fluency and clarity. So if that’s the idea, if art itself is the communication of a particular human experience, then the notion would be to make that experience as deep and as dimensional as a sentient being could handle.

©Lonnie Graham, Memorialization, Acknowledgement, Enlightenment Spoleto Festival, Charleston, SC, Harry Noisette in the Garden of Enlightenment. The garden of enlightenment at the Wilmot Fraser elementary school provided an outdoor workshop in laboratory for school children. The school was slated to be closed because of poor performance and poor testing scores. However after the garden was installed student test scores went up attendance improved and the school stayed open for an additional five years. This piece was part of a triptych done for the Spoleto Festival entitled memorialization enlightenment and acknowledgment.

GC: And your expansion as an installation artist?

LG: The first thing that I did as an installation artist was to get people to understand what it was like to be within immediate proximity of the individuals that were most important to me at that time in my life or even in most of my life. Also understanding that everybody had one [someone important to them], everybody came from somewhere. We all came from somewhere. We’ve all got some level of ancestry. Making a piece that people could react to that has assailed all the senses like seeing and hearing and smell, maybe not taste because people couldn’t eat the installation, but they could touch it and feel it. I wanted that level of access so that if people didn’t understand it, if people couldn’t feel it then there was going to be something in that installation that somebody could relate to.

Then there was another level to it. I have been to the great museums of the world throughout Europe and the United States. You see the bed that these Kings and Queens have slept in. They had the slippers. They had the nightgown. All this stuff and I said well you know they’re people. I watched my aunt Dora brush her hair in the evening. I said, that’s worthy of veneration. Why isn’t my Uncle Floyd’s living room in this museum? Not only that, but not everybody’s related to the Queen, but everybody’s got someone like an aunt Minnie or an aunt Dora or an uncle Floyd or something. I wanted there to be that level of accessibility for people. I wanted people to be able to respond to reality that way.

The next one I did had to do with the mind, and the body. The first one was about the spirit. The next one was about the mind because most people have one of those, some people have lost theirs and they’re still waiting to recover. My father’s mind left him, so I wanted to do a piece about values and appreciating other humans. So, there’s the mind and the spirit, but you have to do the body. The next one had to do with uncle Floyd who used to garden and that one seemed to have caught on because everybody likes to eat. So we got the mind and the body and the spirit.

©Lonnie Graham, 4 The farm stand installed at the Cincinnati contemporary Museum of Art is an homage to African-Americans who worked as sharecroppers in the American Southeast. This fantasy farm stand contained goods from all over the world and was built to represent a large basket of bounty or cornucopia. Sales from the goods of this farm stand were used to benefit a local charity. This effort was meant to bring light to the fact that most sharecroppers are not allowed to sell their goods, never able to travel very far from home, and never realize a profit.

GC: How did the garden project evolve?

LG: The garden came about when one group of individuals in Washington, DC. got it into their heads that women on welfare were living large and in excess so they cut the food stamp allocation to these people. The result of that meant that a vast majority of the people, the recipients, were going hungry. I ran into a group of these women in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, who went into a vacant lot and had found tablespoons and were digging out little patches in the dirt. They went to the drugstore next door and bought seed packets and started to plant seeds. They had no idea what they were doing. I thought what happens if I take this grant that I got and I help these people. That’s money that I got from the government. They could give me money to do an art project, but they couldn’t give these women money to feed their families. I said, okay, I’ll take it on myself to do it. I got the city to give me a bunch of dirt because they had a conservancy where they collected all the wood chips and grass clippings and everything. There was another initiative where they were fencing off properties. I went to Tom Murphy, the mayor, and he gave me a vacant lot. So, I got some dirt, and I got a lot, so now we need to help these people understand how to mess with the dirt. I got people that I knew were agricultural experts, people that only had dirt. I got these Kenyans, these agricultural experts and I brought them over from Kenya to work with the women in Pittsburgh, so that was the African/American Garden project. The Kenyans showed these women how to grow food and grow their crops. Then I wanted these people, the women, to understand what it was like, because they’re Americans, to really not have enough even though they had stuff taken away from them. I wanted them to see what it was like to really start with dirt, with nothing. I took them over to Kenya. We then had this little exchange going over a couple of years. So then you see the evolution. I started as this sort of self-absorbed photographer artist. Then suddenly through no fault of my own, just from listening to people and trying to communicate with them and trying to address people’s needs, I became some kind of a social activist and it all comes from wanting to be more of what I thought I should be.

©Lonnie Graham, Lonnie Graham is seen here working in the field with Turkana Chiefs rendering portraits of the tribal and community members. After the days long discussion about water issues the Chiefs compelled a meeting in a dry riverbed to illustrate the severity of the water issues that resulted from the Ethiopian Chinese and Italian governments damming the Omo River that subsequently dried up rivers and streams and caused the salinization of Lake Turkana. This population is disappearing. The irony is the remains of some of the earliest human beings were discovered within a 300 mile radius of where we were photographing. Sadly the descendants of some of the earliest human beings are now subject to extinction.

GC: Yes, that’s powerful. That leads me to another question that I have around the idea of exchange. I believe that the exchange of values, ideas and experiences are key components in building and activating a community. I’d like to dive into that to understand how you see art playing a role in this exchange and the role of the artist within the exchange of values, ideas, and experiences.

LG: Okay, yeah. Let’s go back. Let’s go way back to before commodification. Actually, before we go that far back, we’ll just go back a few seconds. Can you tell me some type of artwork that is not entertainment or decoration?

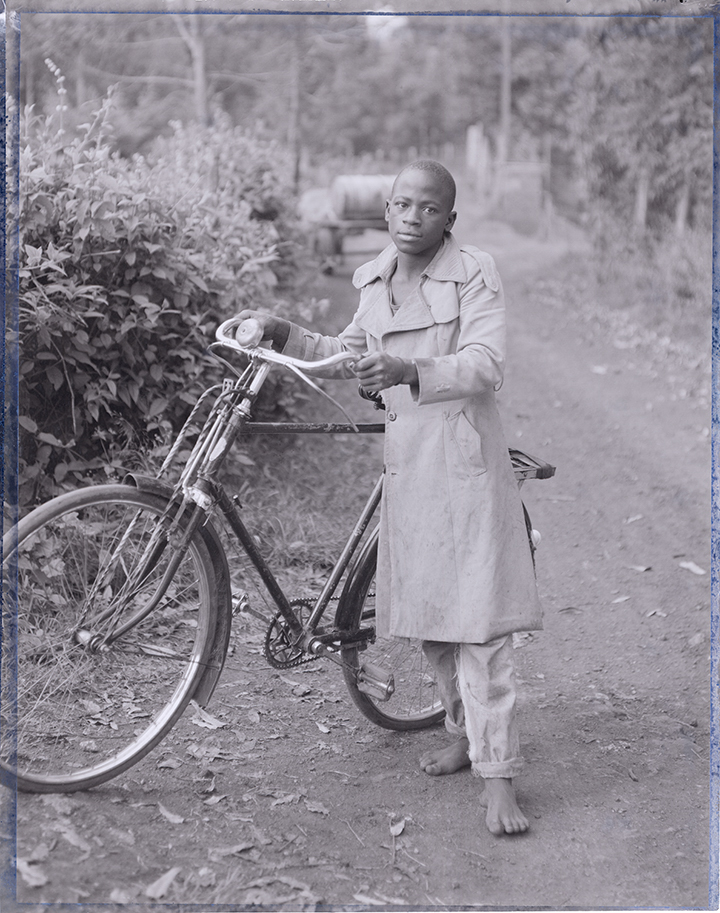

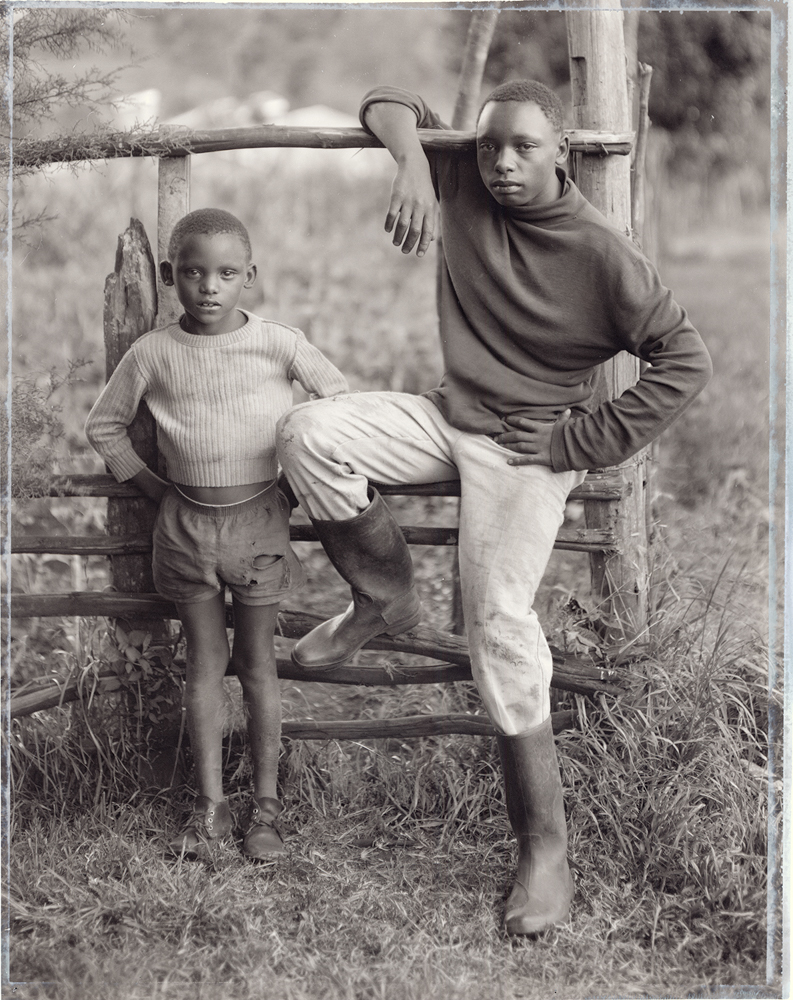

©Lonnie Graham, Muguga, Kenya portrait of two workers resting at the African/American garden project.

GC: It’s a good question. I would say a lot of art that I see in this contemporary era is dealing with political issues, social economic issues, so it’s not really meant to be just a pretty photograph, but as a way to operate on a new level and push us forward. On the other end of the spectrum, I will also say that all art is meant to entertain and decorate in some sense.

LG: Okay. So now we’ll go back. We’ll go back a few hundred years to before commodification, because we all know that that happened around the renaissance when people started to actually pay for this art stuff. There were certain people that had the resources, meaning money, and they were able to get certain groups of artists together to produce the most powerful interesting incredible artwork that had ever existed before that time in their estimation. Now, let’s go back to before that. What you want to talk about is the exchange, the purpose, the cause, and the responsibility of the artist in communities?

GC: Yes.

LG: Okay. Let’s talk about the basic needs of the community. Let’s talk about food. Let’s talk about housing. Let’s talk about clothing. Let’s talk about how you get the food up to your face. Let’s talk about the people that designed the houses. Let’s talk about self-adornment, which is a form of decoration. Let’s talk about ritual, which is something that humans are prone for some reason to do. We like some degree of regularity and predictability. We like thinking that we’re not alone. We like thinking that there’s somebody watching us. That there’s somebody with us, that there’s somebody who can help us in times of stress and we’d like to be able to communicate because we have this enormous incredible ability for language. We’ve got all these different ways that we can communicate with each other. Let’s tie something visual onto that. All of these ways that exist, that have existed, that people have used over the eons since the inception of humanity to communicate an idea, to clothe ourselves, to address a deity, art is embedded within the context of our humanity. It’s not something that we came up with. It’s not something that we go to school to do. It’s something that we are. It’s just what we do. We use visual communication to help us bring other people in to address a deity, to build a house, to clothe ourselves, to make ourselves look pretty to attract other people.

To relegate the arts, which is the way that our little Western minds think, is why we’re having so much trouble in society with the arts today. It doesn’t mean anything; it doesn’t have any value. We don’t need to teach children to paint. We don’t need to teach children to do music. They can learn that later. We don’t need to teach them to do any of that. What about a house? Oh, no, that’s not art. That’s architecture. What about books and magazines? Oh, no, that’s literature. It’s pathetic. There’s pathos that’s involved in this thing. Society has separated their concept of art so much that if it even begins to resemble something that they NEED it has another name. That’s design. No, that’s architecture. No, that’s literature. That’s poetry. That’s not art. Art, that’s that stuff you put on the wall. That’s the thing that those crazy people do. You don’t want to be involved in anything like that. In fact, it doesn’t have any value until you die because we don’t want to have to deal with living artists. They’re too difficult.

GC: We have too many opinions.

LG: They got too many opinions. It’s sad. If you look at children, you give little tiny people stuff to work with, they just start making stuff. You give them a crayon, they’ll draw something, they’ll make marks on the floor. Give them some Play-Doh or something, and they start making little creatures with it. Kids are so funny because if you give them a piece of Play-Doh it doesn’t look like anything it just looks like some squishy stuff, but it’ll have a name. They make a little weird looking thing, and you ask what is that? They answer, “No, that’s who. That’s Angela.” What’s that one? “Oh, this is Peter.” What are they [Peter and Angela] doing? “Oh they’re going to the market.” Now they’re like sculptors and playwrights. They have all these things that they see. They’re trying to communicate these experiences that they have that live in their heads. It comes out. It’s in them. What happens to that creativity? What happens to that sensitivity? You know they beat that sensitivity out of them and then they beat algebra into them.

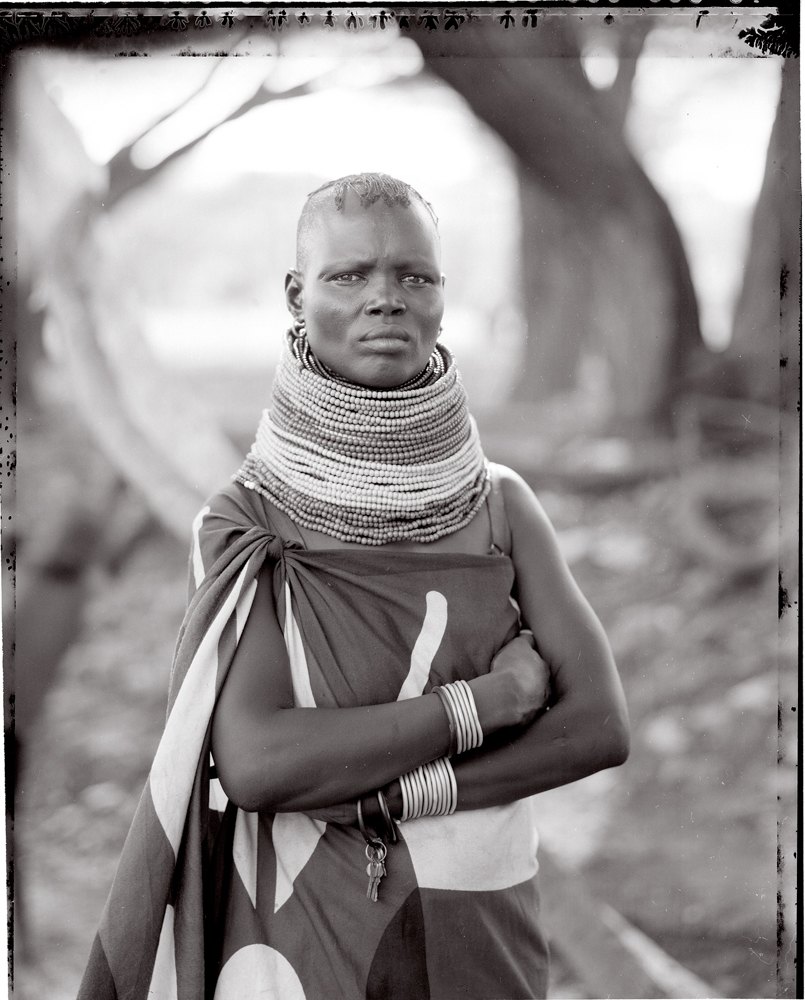

©Lonnie Graham, Turkana woman, dry riverbed near Lake Turkana Northern Kenya, A Conversation with the World, portrait.

GC: Right, so the imagination then doesn’t hold much value in the context of our society.

LG: Isn’t that pitiful?

GC: It’s very sad, because in my own practice, the imagination is so important.

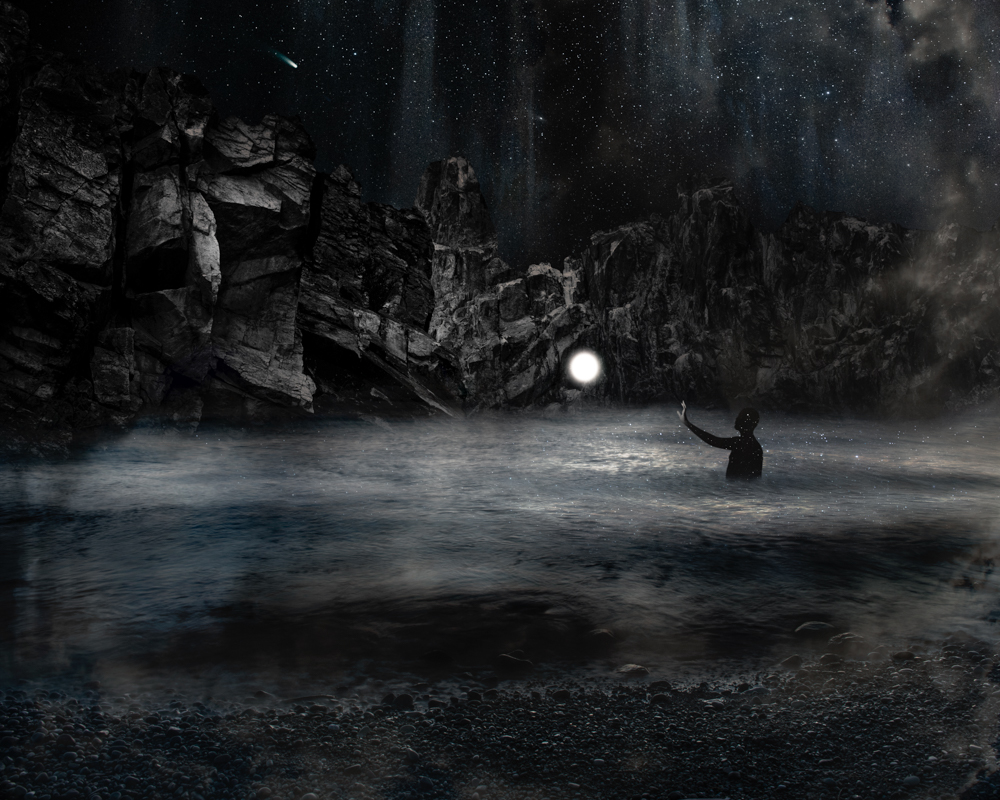

LG: Your work is beautiful in that way. I mean your work just borders on the spiritual. On the end of what normal people think is intangible. It really is transcendent, and it really helps us. Even if it just begins to help us consider something that we don’t encounter every day. It begins to work and it’s successful and your work is beautiful that way.

GC: Thank you. I remember when we spoke during NEPR I wrote down two questions you asked me to consider. What do I want my work to do for my audience and then what am I trying to achieve through that process? I thought about that in terms of the imagination and exactly as you just described. I want to push people to think the impossible is possible by creating unrealities. Creating these things that cannot exist, at least in the tangible physical sense, but that presents the mind’s ability to try to bring those things into existence. The imagination, you talk about beating it out of a child, and I think about that often in terms of what art can represent and how one reaches into the core of themselves to express it, to express their practice, which is sort of childlike. That curiosity, the questions of what if and why, I think it’s important for artists to ponder as well.

LG: It’s important for everybody.

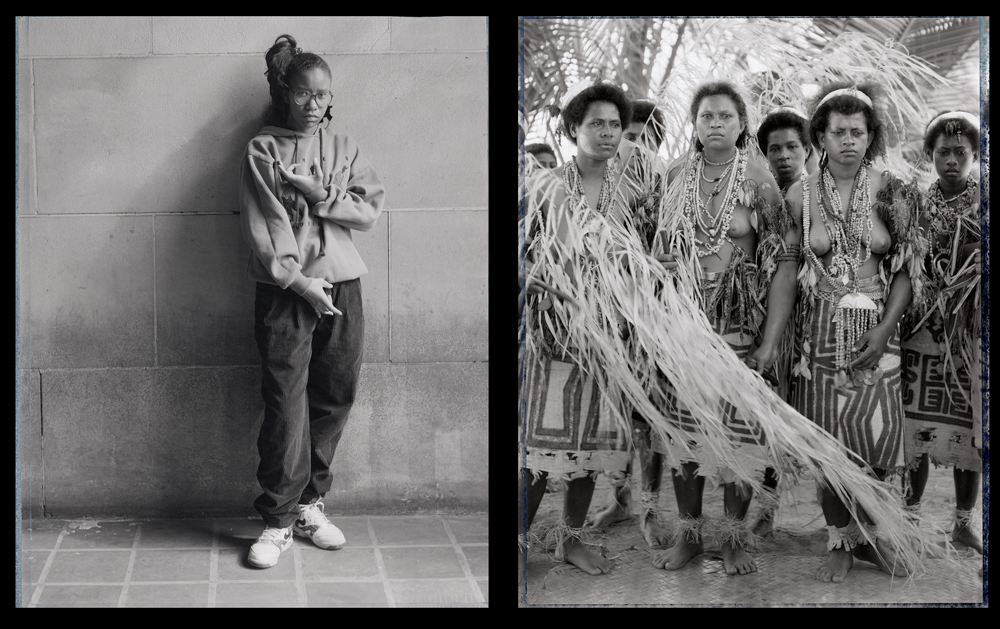

©Lonnie Graham, Tribal nation. This diptych illustrates the need for humans to affiliate or to align themselves with like-minded individuals through ritual or practice or the establishment of a core belief or value system. Margaret on the left is shown broadcasting her group affiliation through over gesticulation, the warrior women of Papua New Guinea stand as they illustrate their tribal affiliation in Ganjiga, Collingswood Bay Papua New Guinea.

GC: It is. You talk about humanity a lot. Viewing your practice, holistically, humanity is centered in what you do. You’re thinking about the needs of the community and looking at our commonalities. You are also looking at how these communities are built and advanced and also the individual humanity within us as well. So I’m wondering how you came to that idea. How did you come to manifest such a concept in your work?

LG: It’s unavoidable. The way that we exist in the world is through the course of our common humanity. For better or for worse. You know, we’re not dolphins. We can only make other humans. That’s it. We can’t make another species. And that’s at the bottom of it. We can mix up and we can make different colored people. We can make all kinds of different colored people, which is really wonderful and amazing. Ultimately, they’re all people. And it’s important to hold all of our rituals and habits and ideas sacred because it’s a part of our past and the future. It’s important to really honor the integrity of all these individuals beliefs, but at the end of it, here we are. And sadly we’ve evolved to the point where we’ve forgotten about where we came from. We’ve taken control of something that I don’t think we completely understand. What we’ve mistaken for progress and intelligence I believe is actually blindness and neglect. Because in the past, if we go back. Way way back. People existed for hundreds of thousands of years and left us an incredible environment. They came and they left without a mark, without a trace, without waste. And then here in the past few hundred years we just buggered it up.

©Lonnie Graham, Adia, Gorée Island, Senegal, This woman consented to be photographed in the afternoon sun on Gorée Island near the slave castles that contain the door of no return. Adia has been included in the Conversation with the World project.

GC: Just destroyed it.

LG: To the point now where we’re trying to cook up a way to screw up another planet, let’s go to Mars.

GC: Exactly, it’s amazing but also terrifying.

LG: I know. Mars doesn’t want you. Mars is like y’all got your own problems. Like y’all deal with your stuff.

GC: Right, saying, stay over there!

LG: We got our stuff, y’all deal with your stuff. You wait till I get to Mars it’s going to be like “oh I can’t breathe.” Like no kidding. We probably messed that up and came over here and now we messed that up and are trying to go back.

GC: You know, I wonder if Mars or other planets in our solar system is a reflection of a very distant past that we have no knowledge of or the point of our future in which we will exist or cease to exist. Especially when you think about Mars and that scientists believe that water existed there and that there possibly could have been life there. Then there’s all these artists’ renditions of what it could have looked like billions of years ago. But yet it’s this desolate rock floating in space. Similar thing with Venus, with the intensity of the gas and the pressure and the heat that’s there. But also some scientists believe that perhaps at one point Venus held life and that possibly it was a lively, vital planet. It’s interesting how we look at the planets through the past, present, and future.

LG: Yeah, so here we are. Since we’re here now, then the idea, because we’re not going to live very much longer. I wonder if we can kick the habit. If we’re supposed to be so smart, I wonder if we can get away from this caveman reflex where if we see something we don’t recognize to kill it. If we see something that doesn’t look like us, we fear it. If we see something that we don’t agree with we shun it. Rather than taking a few moments to consider the fact that yes, indeed, here we are. We’re all here. We’re humans and even though this other person doesn’t look like or think like or talk like me, I wonder what they’re actually thinking and feeling.

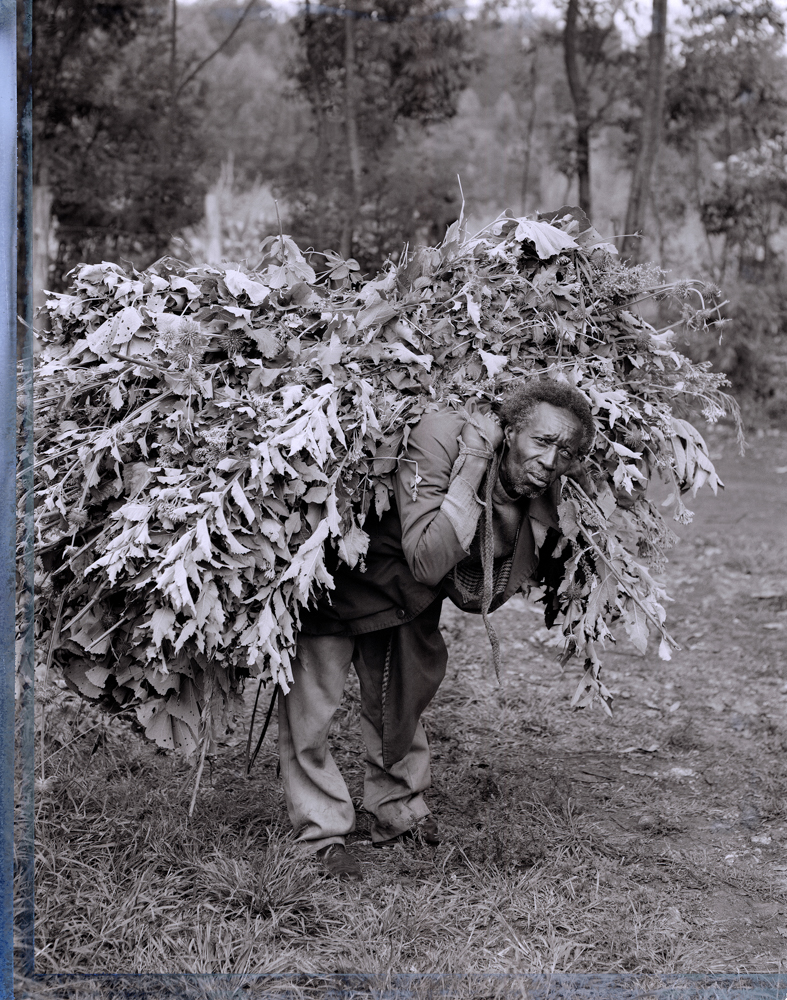

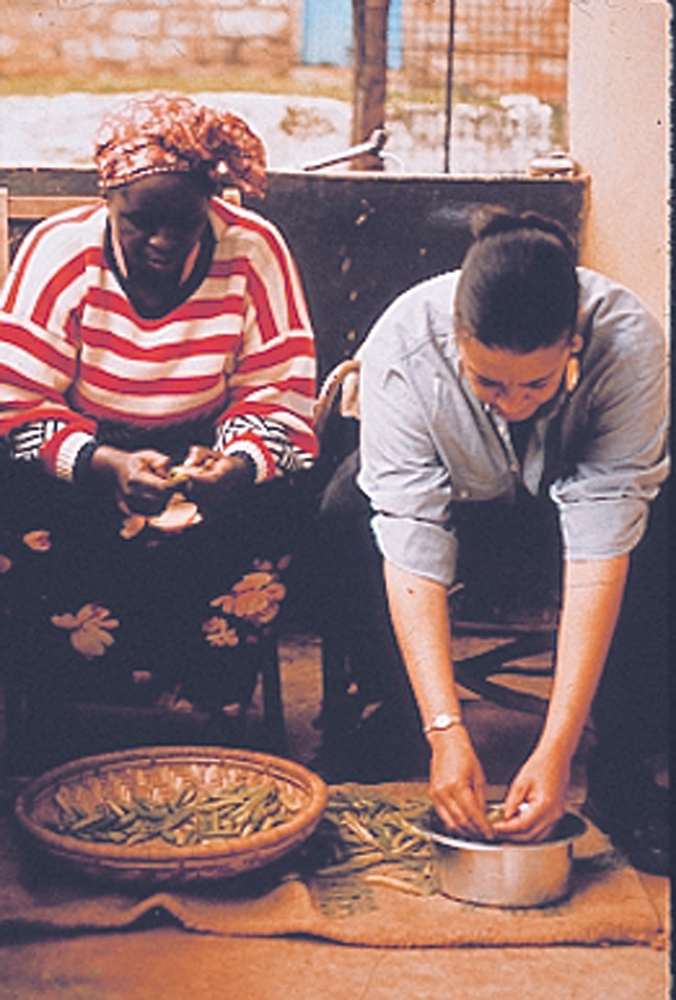

©Lonnie Graham, Muguga, Kenya, the African/American garden project. Jean, a librarian from Pittsburgh Pennsylvania shells peas with Mrs. Hilton Karioki on the porch near the garden site. This multi year project involved the exchange of Kenyan agrarians and individuals impacted by food insecurity in Pittsburgh’s Homewood section. Newt Gingrich and his tea baggers entered into American politics with the aim of cutting waste and subsequently reduced food stamp allotments for millions of people causing deep food insecurity for recipients of food stamps and welfare recipients. The African-American garden project was conceived to help both populations of Kenya and Pennsylvania understand the resources and cultivate a cultural exchange.

GC: So that’s interesting in terms of common humanity and what that presents us with. I feel like people might say that the common humanity of our species is reductive of people’s culture or heritage. Or that common humanity doesn’t give room and space for that. I wonder, then, if that’s the case, then what is the other option? Can seeing the common humanity actually rejuvenate or reinforce our culture and heritage through these links and connections, reducing this idea of separation that is created within contemporary societies?

LG: Yeah, it’s reductive, there’s no doubt. It is reductive, but it’s not exclusive. Let’s just say we’re going to take the past 500 years. You can’t even read the language that those people used 500 years ago. So now here we are, the great communicators in the age of communication. 500 years from now, what kind of languages are people going to be speaking? In fact, some of the only languages that we can remotely imagine are what? Pictures! The little pictures on the wall that somebody drew thousands of years ago.

GC: Right, okay. Cave paintings, hieroglyphics, motifs and patterns and Earthworks

LG: That’s right. They don’t need a language as we know it. They don’t need that kind of written language, but we can celebrate that they were after something. We know that they were after food. We know that they were in the cave because it’s probably a house. Look at all of that that we have in common with those individuals. I’m not about being exclusive. We tried that already, let’s try something else.

GC: I share that sentiment. It’s interesting to think about the larger context of how people think and then with all the ideas that you bring up about the essential necessities of what it means to just be human. The history that we come from and the humble beginnings of living in nature and caves. Fast forward to 2021 and we build this huge gap, this chasm of separation because we have technology, and we think they didn’t. Even though they did, of course, with other means.

So, then, thinking about all of that. How do we create that dialogue between different peoples? You’ve traveled the world and gone to several countries and have done lots of different projects with these individuals. How do you create that bridge? How does art function as that bridge to connect us to one another? We have the pictures, and we can read that and in some ways understand each other through that mechanism, but what other ways are there?

LG: Yeah. You answered the question because pictures are the bridge that connect people. People see a picture and suddenly it lays the foundation for, and opens the door, to become a vehicle for communication and for the exchange of ideas.

GC: Okay, pictures are the bridge. I like that.

LC: They can be, you know they open the door a little bit. Somebody was asking me this morning, one of my students called from China. They were getting ready to go into this village, this old ancient village north of Beijing and wanted to know what to do, like how to take pictures and how to talk to people. I said, well, when people see the camera, they’ll come over if they want to engage and if they’re shy they’ll just run away. If people want to engage, if people are open, then they’ll wander over and you can start a conversation with them. The idea of just taking a picture and talking to people and engaging people in the process became extremely valuable because in the end it was less about me and more about things that we can share as people. I could out clever myself, I could try to make a better picture than the one I made last week and continue to build on that, but eventually that’s going to be a trap. I just wanted to bring it all back down and do one picture, one person at a time and actually get to know these people at least for a moment. Let me appreciate this person, let me just take the time to look at these people and not objectify them.

GC: It makes me think of the idea of mindfulness. In Zen meditation it’s about being present and aware. There’s something a friend introduced me to called the Zen Koans. These Koans are supposed to stop you in your tracks and stop automatic thinking so that you actually have to be aware of your thoughts. You have to be aware to stop certain thoughts from happening, but also allow other thoughts to proceed. It’s about a balance of control and letting go of that control. But it seems like what you’re really doing in the process of making pictures, what you’re more concerned with, is that exchange of ideas or the values of your own with another person and then how that cultivates that sense of connection. Which then in turn, will show up in the pictures and installations or other mechanisms or mediums that you may pursue to express that interaction. I don’t think there’s really a question in there, more of just a comment.

LG: I’m happy and thinking, appreciating your words and your thoughts and your insights and mostly your level of sensitivity. Thank you.

GC: Thank you. Thinking about the idea of spirituality in the act of image making, I’d like to dive into that. I wouldn’t call myself a Buddhist or anything like that. I don’t really follow a specific dogma. You spoke earlier about ritual which has me thinking about spirituality in terms of humanity and connection. I wonder if that has any influence on the way that you think about things, how you operate in your own life or how you operate in your practice.

LG: I’m a human. The world is so big and the universe is inconceivable. It’s just silly to think that we can imagine anything outside of ourselves, any other kind of entity. So we really try to look for some signs of it. We try to look for some evidence. Oddly enough, we wind up deifying the patterns, the evidence that we see in the world. The rising sun becomes sacred. The changing seasons become part of the larger ritual. The stars in the sky become part of something that we can see and understand on some level and then project our values onto. Isn’t that what happens? But then, if we let things go if we let things be, according to their own nature and appreciate that and then try to see where we fit in, then, I think that becomes an even more humbling experience. To try to conceive of our place, our existence in the world.

©Lonnie Graham, Common ground project HOME, Philadelphia Pennsylvania. After a beloved Catholic church was destroyed in the church fire, residents felt bereft of a place to contemplate and worship. In collaboration with Lorene Cary and John Stone, the sanctuary was constructed on the side of the former church where residents would go to feel safe, have a place to sanctify marriages, births, or unions, the interior of the remaining rectory was transformed into a repository for oral histories that had been collected by local youth. During the course of transforming the rectory into a public common room local youth were trained in the use of video cameras and recording equipment and so deposed senior residents in the neighborhood of their oral histories. This led to a kind of cultural exchange between generations. The community received a Macintosh computer with video and editing equipment along with still and motion picture video cameras. Custom-made furniture and artist wallpaper was also installed at the site.

GC: So, in a sense, it’s about being an observer.

LG: Yes, and trying to be objective about the reality and about the context that we function in.

GC: Okay. I feel like there’s that connection, again going back to the essential needs of an individual or a community. You know to deify the rains because that’s going to provide water and wash the soil bringing nutrients to crops. Or the sun providing warmth and the land providing protection. What I’m saying is that spirituality, in the way that you see it, is connected to our essential needs for existence.

LG: Yeah, it is to go out and witness. I’ve been trying to do landscapes for the past 20 years. I think I’m just beginning to understand it; to go out and witness. You go out depending on where you are, like at three or 4 o’clock in the morning. And to just sort of stand there and watch as the world turns. And you know, witnessing and observing is really incredible.

GC: I agree. I like that.

Shifting gears, you’ve seen photography change over many years. With that change, what is it that you hope for the future generation of image makers? What ideas do you want to see them pursue or how they think about photography and other mediums?

LG: I really do wish people would suppress the ego and get beyond themselves and just try to use this technology to access the capacity to make images in a way that defies provincial definition and perception. How can we use these instruments at hand to actually make a difference. It’s probably going to be something that we can’t quite imagine. In 1990, nobody could imagine that a car would drive itself. That was like the Jetsons.

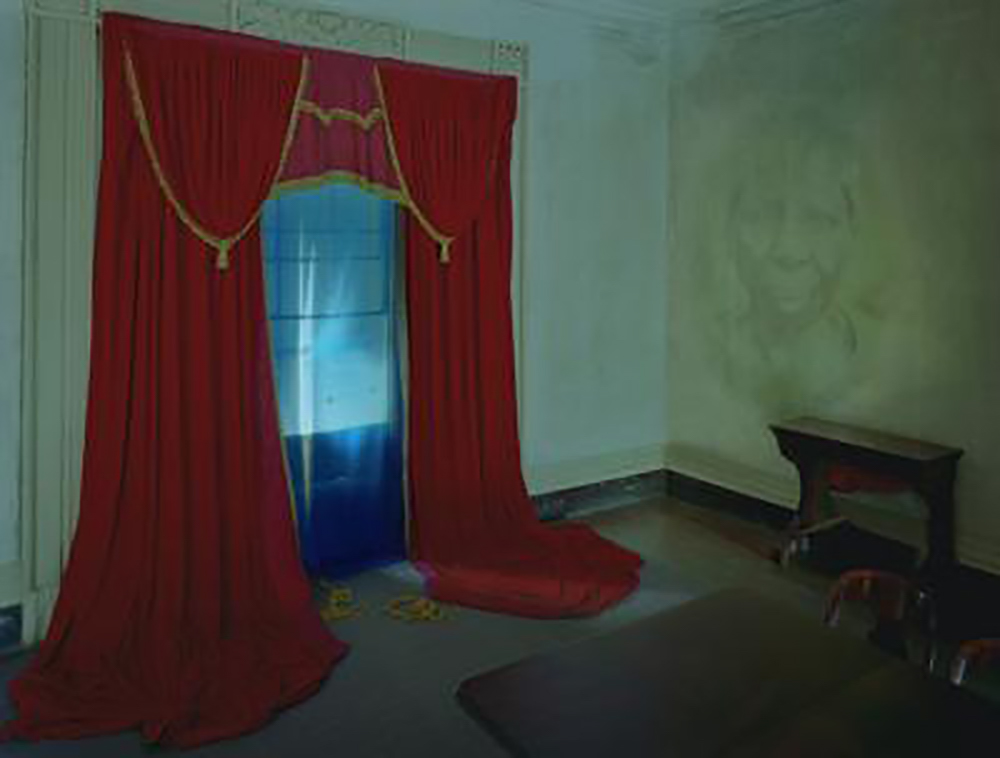

©Lonnie Graham, Memorialization, Acknowledgement, Enlightenment Spoleto Festival, Charleston, SC Installation on three sites acknowledging African Americans. The site shown here is meant to be an acknowledgment of the individuals enslaved here at the Aiken Rhett House, and urban plantation in Charleston South Carolina. The 14 foot tall drapes constructed according to the antebellum style of the time are a metaphor of excess as they pool and puddle into the floor. The golden braids you see cast on the floor is meant to be a metaphor of the loosened bonds of those in servitude. The blue sheer curtain is embroidered with the Big Dipper. Individuals in the courtyard looking into the big house would see, not the intimacies of the landowners, but a symbolic roadmap to freedom. On the right-hand wall of this installation were a series of images, portraits of the descendants of individuals along the West Coast of Africa who may have been somehow related to the individuals that were enslaved to build the Aiken Rhett House. A photograph of these people in West Africa were then projected in a loop and arranged the images so they would fade and dissolve as if the faces were emerging from the walls themselves. So great was their guilt, the workers at this museum found this installation so disturbing it was ordered to be dismantled the day after its installation.

GC: Yes, I remember watching that, absolutely!

LG: Absolutely in 1962, they told us that in the future whenever you call somebody on the telephone, you’ll actually be able to look at them.

GC: Wow, and here we are!

LG: And here we are. It could happen, so yes imagine image makers like what could we produce? Maybe not, maybe it’s not even a thing. Maybe it’s just like how we would use pictures to help people understand how to use pictures in an effective way?

GC: Okay. So it’s posing that question for the future generations, which I guess would include me and others in my generation and beyond.

LG: Yeah, maybe so. I’m not smart enough to answer it. I’m only I’m only stupid enough to ask the question.

GC: Well, I think there’s a whole level of sophistication in terms of not seeking the answer, but actually wondering if you’re asking the right question.

LG: Oh. Thank you. Yeah.

IMAGE

GC: And I will say what inspired that thought is the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

LG: Yeah, I think I read that when it came out.

GC: Okay. Yeah, I recently listened to it in an audiobook a couple of months ago and then I just watched the movie as well.

LG: Yeah. That’s a fun one.

GC: It’s a great movie. It comes to that point where you know they asked the super computer, Deep Thought, what’s the answer to life and the answer is 42. The characters said that doesn’t make any sense. So it begs the question. Are you asking the right question in order to get the right answer? I think it is important for the future generation of image makers, which includes anybody who’s making images right now and then people who will come after us, to question the questions they are asking.

And with that I think that is a great place to end. Thank you so much Mr. Lonnie Graham. I really appreciate your time.

LG: That was so nice. It was so nice of you to think about me and call.

GC: My pleasure! Thank you again. I really appreciate your insights.

*Interview was transcribed and edited for an easier reading experience.

Granville Carroll is an educator and Afrofuturist photographer currently based in Rochester, NY. Carroll received a BFA in photography from Arizona State University and a MFA in photography and related media from the Rochester Institute of Technology.

Granville Carroll was recently named as one of 47 artists on the inaugural Silver List through the Silver Eye Center of Photography. Carroll’s work has been exhibited in the United States and featured on multiple online platforms such as, Phases Mag, Artdoc Magazine, Humble Arts Foundation, Lenscratch, Photo-Emphasis, and Float Photo.

Follow Granville Carroll on Instagram: @granville_carroll

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026