Photographers on Photographers: Amina Gingold in Conversation with Cecelia Condit

Photography is just one of the tools Cecelia Condit uses to express herself. Ranging from video, song, and installation, she is primarily a filmmaker and educator who incorporates many elements into her practice. You might recognize her as the woman behind Possibly in Michigan, a video that has taken the world by storm. In 1985 it was featured on the Christian program, “The 700 Club” and is now inspiring today’s youth on TikTok, leaving the hashtag #PossiblyInMichigan with almost 40 million views. It was my senior year at the School of Visual Arts getting my BFA in photography and video, when a professor of mine shared Beneath the Skin with me. I instantly felt that I had struck gold. Cecelia Condit? Her stories are a mash up of first and secondhand accounts that are visually striking and saturated in emotion. Her perspective is dark, familiar and at times, comical, while touching on the suburban landscape and its oddities. Cecelia offers the viewer a glimpse into her world, one that overflows with rhymes, grime, and fantasy.

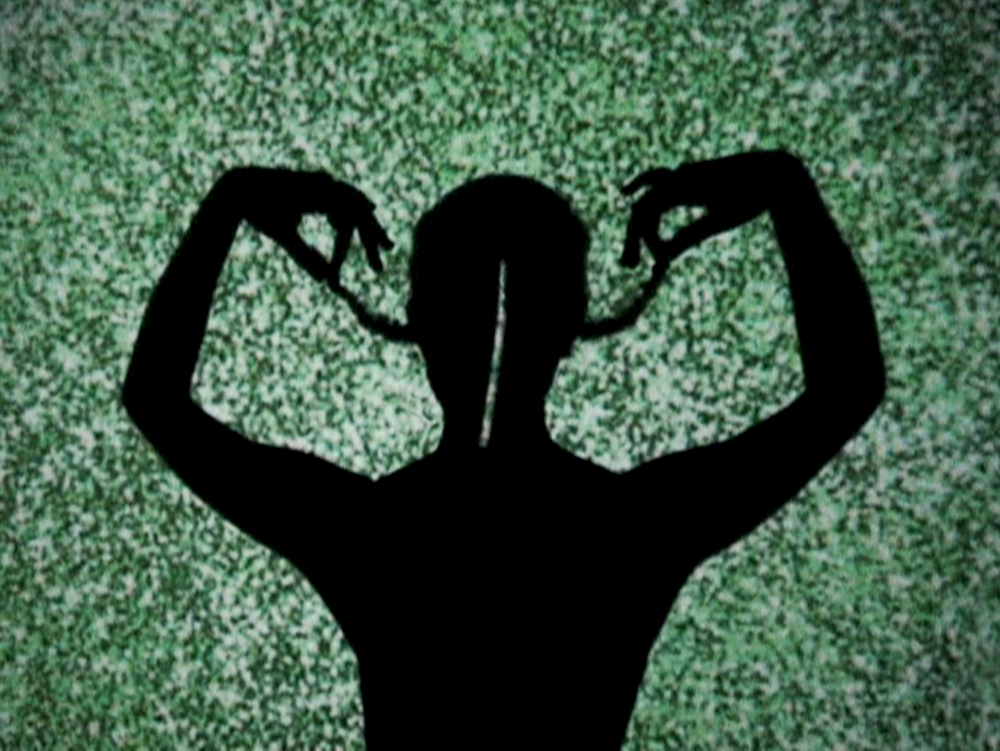

Since 1981, Cecelia Condit’s videos have created heroines whose lives swing between beauty and the grotesque, innocence and cruelty, youth and fragility. Her work puts a subversive spin on the traditional mythology of women in film and the psychology of sexuality and violence. Exploring the dark side of female subjectivity, her “feminist fairy tales” focus on friendships, age, and most recently the natural world. She has shown internationally in festivals, museums and alternative spaces, and is represented in collections including the Museum of Modern Art in NYC and Centre Georges Pompidou Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris, France. She has received numerous awards including grants from the Guggenheim Foundation, American Film Institute, National Endowment for the Arts, and the Mary L. Nohl Foundation. She is a professor emerita in the Department of Film, Video, Animation and New Genres at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, USA., where she was the director of the graduate program in film for 30-years.

Follow her on Instagram: @ceceliacondit

Amina Gingold: What is something you find beautiful and what is something you find ugly?

Cecelia Condit: The natural world has beauty for me. I’m drawn to it. For example, in your work, Amina, Night Call (2020) when your grandmother is running across a field trying to get away from someone trying to abduct her. I thought that was especially powerful. I believe that the natural world is something that has been in my work very early on. Even in Possibly in Michigan (1983) I show a parking lot and mall where there used to be woods. I view myself as an environmentalist of sorts. As for the ugly, I guess the sense of not having a voice or to be silenced not just by yourself but by the world, and the universe. It seems to me that the universe can bless you, but it can pay no attention to you at all. It’s just how the synchronicity of life works.

AG: How would you describe your cinematic style or approach to video?

CC: I don’t know exactly what I’m ever trying to say when I start a piece, though I don’t think that is apparent by the time it’s finished. Sometimes, I begin with a story and it turns into a poem. It seems I don’t have to know what I’m doing immediately, though for me a narrative is harder to do. Sometimes I find my storyline after I’ve begun shooting. Whether it’s because of who I’m shooting with or who’s in front of the camera, those things inform the structure of the video. That’s one way that I can operate. The other way I operate is when I’m trying to find out more about what I feel or what the world looks like to me. Like in my new film that I’m thinking of calling An Artificial Friend in which, I consider, “What is consciousness?” I know that great minds can ponder what consciousness is, but I try to believe that what I have to say, even as a small person, is also important.

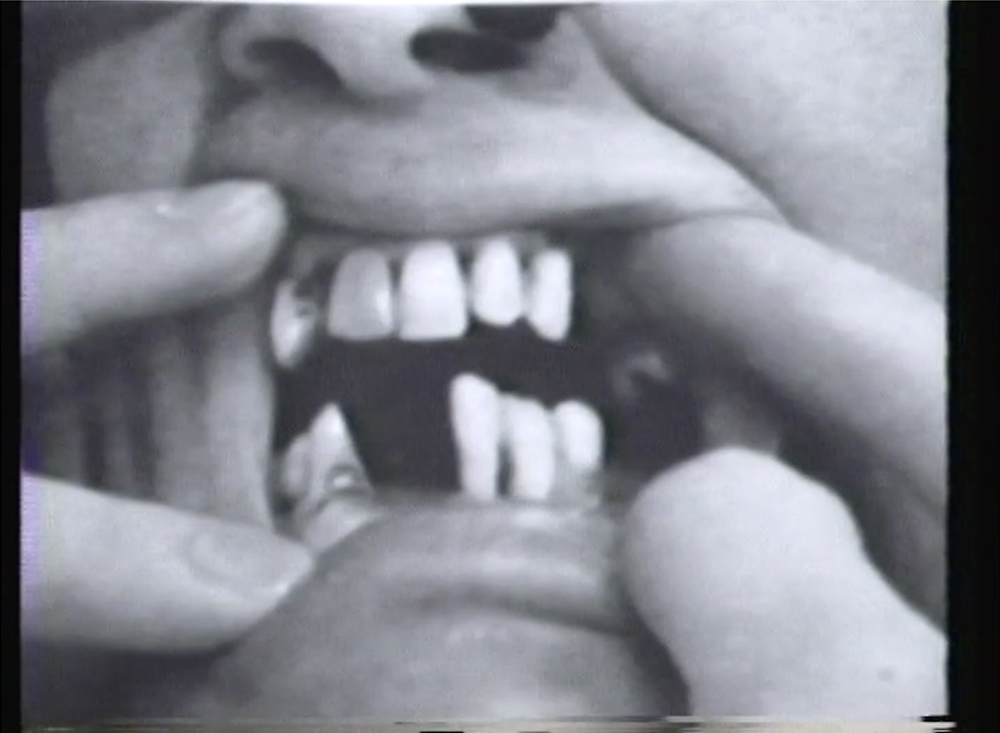

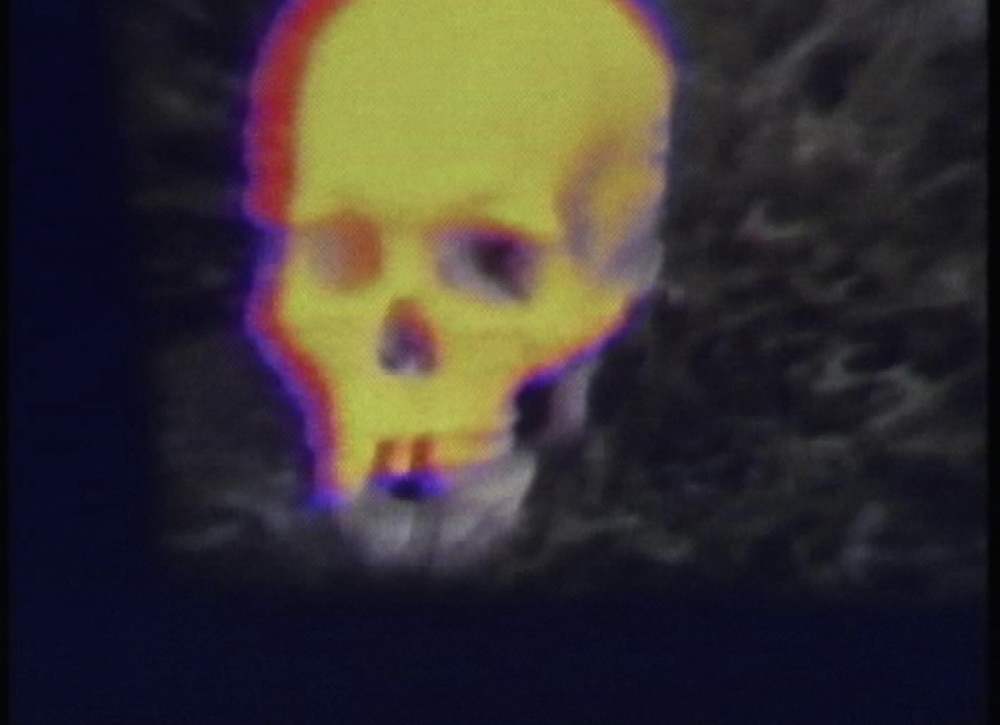

AG: Your work from the 80’s, Beneath the Skin (1981), Possibly in Michigan (1983), and Not a Jealous Bone (1987) are particularly experimental in their nature compared to your later videos. Your usage of projection, distortion, color, sound, found footage, and layering of each frame between the subject and camera is something that has grabbed my attention. What was your very first introduction to experimental film? Was there a favorite artist or “aha” moment that influenced you in the making of these first films?

CC: There have been “aha” moments for me. I never really knew about experimental film until I was doing photography in graduate school. I went to a screening and saw Nam June Paik’s Global Groove (1973) and I went out of my mind. I know that there was wonderful video work being shown around it, but it was the only one that I could remember! I knew then that I could experiment with music. I think Devil with a Blue Dress On is such a brilliant song and it is ingrained into my developmental history. I could imagine this woman, this devil with the blue dress on, and of course, it was a male gaze, which I had been trying to figure out my whole life. That was a major moment and then a few years later I did Beneath the Skin (1981) and I wanted a song. However, with that particular film, my story was the center of focus because it was so real to me, and I was being crushed under its weight.

AG: I see similarities between your work and other photographers such as Mary Ellen Mark, Diane Arbus, Sally Mann, and Anna Gaskell. A lot of these female artists photograph with the intention of showing the darker side of things as well as their choice to focus on people and many times specifically portraits of adolescents. Do their viewpoints resonate with you and the childlike landscapes you create?

CC: Diane Arbus’s work was another “aha” moment for me. You did pinpoint that very well, Amina. I saw a show of hers in New York when I was young. At that age, the photographic work I was doing was strange – actually precursors to my videos. I was trying to get to some very private, dangerous place that felt like home. I thought that Diane Arbus was so brave and I felt so timid. I’ve been influenced by her fierceness.

AG : How do you define a male protagonist?

CC: I think a male protagonist can be very subtle. They can almost be wonderful men who have hurtful one-liners or they can be terrible and kill you. There’s the danger of being silenced, which surprisingly, I found could happen quite easily. Men can isolate you from the most powerful part of yourself without you knowing that it’s happening. You just fall into step. I think that maybe that’s the most dangerous protagonist.

AG: Your work is extremely performative, have you thought about creating live performance pieces in the future?

CC: If you had asked me this question long ago, I would have said yes. But since we are talking about my future today, I would have to say I don’t think so. I always thought I should do a feature. And at the end of every video, I always thought I should do a performance, but I never did.

AG: I’m drawn to the starkness between the silliness and horrific elements in your work. How do you find a balance?

CC: I like to have fun things in my work. I think there was a time when I lost it because I couldn’t find it in my life. Maybe because of the gravitas of having a teaching job, being a mother, and a wife, with all of the craziness of making sure your children have good childhoods. That was the middle period of my work – other than Annie Lloyd (2008) or with All About a Girl (2004), where there is a little girl and a rat who are twins. However, one is dead and the other one is alive. Strangely, the dead one seems to have more fun. At those moments, I think I’m pretty funny. But, as a teacher, I always told my film students that no one gets to kill or hurt a woman in a project in my class. I just can’t take it now. I don’t want to see another beautiful dead woman romanticized on film. It’s not funny.

AG: What do you think about the game telephone and how easily words can be misinterpreted? The final story line is changed from its original form after being repeated through multiple participants. I think a lot about this game when I interact with your work. Memories and stories you speak about become so malleable, that the end result is never what you expected it to be.

CC: Yeah, I can only agree that stories get handed down and then become something different. It’s just like when we’re talking about memories. The stories go deeper and deeper. Growing older, I’ve found that it isn’t just the things that you think you know. You start getting glimpses of other things that happened around what you know happened. They become punctuations. The story becomes so large that you start remembering conversations and other things that very well may have happened. Endless.

AG: How has technology influenced the ways in which you create your films?

CC: It was easier not working in analog, but it’s never easy making work. Beneath the Skin (1981), Possibly in Michigan (1983), Not a Jealous Bone (1987), Oh, Rapunzel (1990 re-edited in 2008), and The Suburbs of Eden (1996) were analog. I made the switch, and it was a hard switch to digital. It took me a while to get the aesthetic down. As video got “cleaner” or closer to reality, you had to work differently when presenting your subject 2nd generation. Jill Sands reduced brilliantly in analog. When I first met Jill, I knew that I had found a star. Analog allowed me to fill up the frame with these fanciful things: murders, dreams, and fantasies. However, I don’t think there’s a good or bad way to make work. I have my cell phone and another better video camera, that’s good enough for me, though I don’t like being in the woods alone with an expensive toy. But, technology does impact what you say. If today you’re working in older mediums, then maybe there’s a sense of looking back or distancing that’s happening.

AG: What was your thought on making all of your work open to the public? Not a lot of artists do this, especially many experimental filmmakers like yourself. Is anything off limits?

CC: Possibly in Michigan (1983) isn’t just like any other film of mine. It’s the film that has a real internet presence and brings the rest of my work an internet exposure that it probably wouldn’t have otherwise. When Reddit happened in 2015, and an excerpt of Possibly in Michigan (1983) was on its front page for a week and a half, one of my distributors, Video Data Bank tried to put out all the other website fires. It was impossible to get the excerpt off the internet at that point. I thought about it for a year, and then I started thinking that maybe I should put the full version of the film online as well. It wasn’t like it was showing as much by then, as work so often has a short shelf life. I went ahead, and put the full versions of Possibly in Michigan (1983), Beneath the Skin (1981), and Not a Jealous Bone (1987) online. They have gotten a lot of views for quite some time now. I had a hard time trying to transition into this new video of mine that I might call, An Artificial Friend, which hasn’t been released yet. I think of it as a mature piece. I’m considering life and the world I live in. It’s a different stage of life piece. I know younger people are also grappling with the same thoughts that I’m questioning, but this would be the first piece I’ve considered not putting online.

AG: If you could collaborate with anyone, who would it be?

CC: Nobody. I tried collaboration, and it wasn’t good for me. It feels like getting lost. I have things I need to say by myself. The minute I think of collaborating, we’re talking about a different kind of film. I’ve had such a hard time finding a voice. It has been something I’ve struggled with my whole life. Now I have a cadre of friends who look at my works in progress, and it’s great. Without them, my work wouldn’t be half as good.

AG: Do you think you’re haunted?

CC: Probably. I’ve been thinking a lot about my mother recently. The last few weeks I worked like crazy to get this new video close to done because I wanted to show it to some people. It’s about something that I got from the energy in my childhood bedroom, the woods and the air around my house growing up, from walking up to the third floor at night, to the simplest things I absorbed. When I go to sleep, I think about how the mind and body are connected. My mother had so many things happen to her body that she couldn’t emotionally handle. I started thinking about the many haunting aspects of this unusual woman, and what I inherited from her. It’s not something that I usually think about, but I have had time to reflect on it this year. So maybe, if I had to pinpoint where I was wandering in my haunted-ness, it might be found in my film Annie Lloyd (2008).

Amina Gingold is a photographer and experimental filmmaker living and working in New York, NY. She graduated from the School of Visual Arts in 2020 with a BFA in photography and video. In her current work, she focuses on how femininity navigates through male-dominated environments. Views of oneself, body image and perception are challenged in these spaces.

Follow her on Instagram: @aminagingold

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026