Publisher’s Spotlight: Conveyor Editions

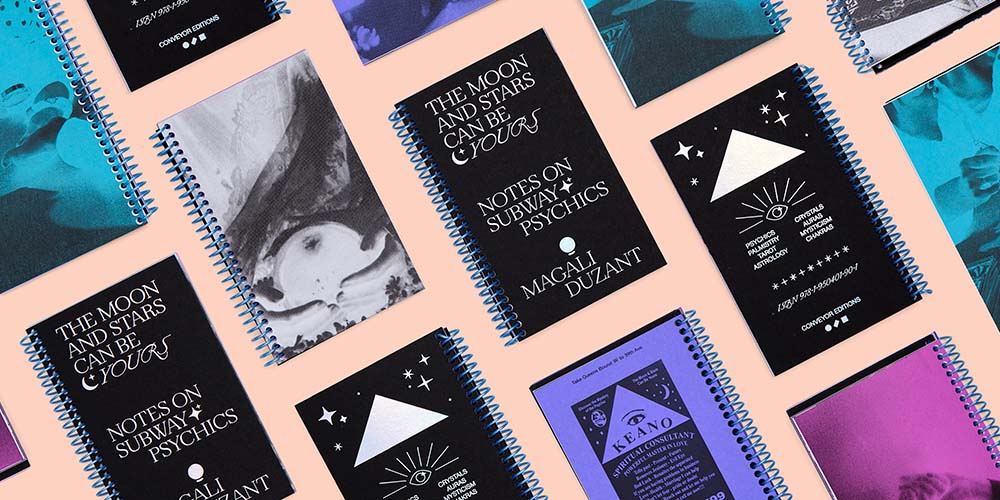

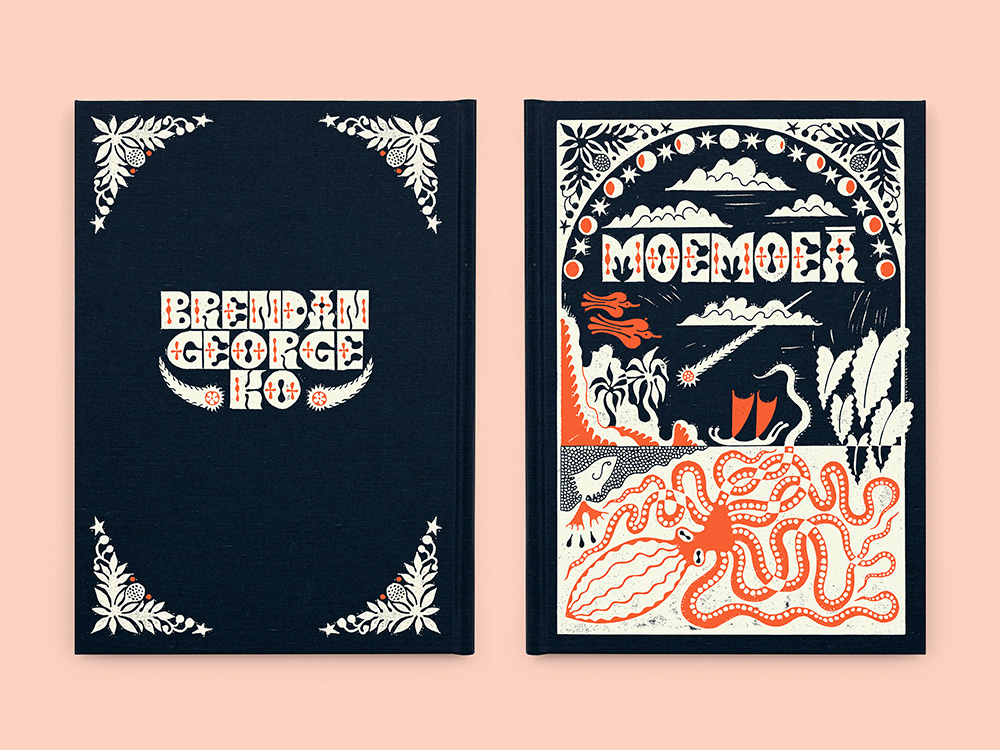

©Conveyor Editions, Front and Back Cover for Moemoeā by Brendan George Ko, Cover Illustration by Sophy Hollington.

These past weeks has been all about books on Lenscratch. In order to understand the contemporary photo book landscape, we are interviewing and celebrating significant photography book publishers, large and small, who are elevating photographs on the page through design and unique presentation. We are so grateful for the time and energies these publishers have extended to share their perspectives, missions, and most importantly, their books.

Conveyor Editions is an independent publishing platform for artist books and magazines at the intersection of photography, science, natural history, with an occasional foray into the mysterious and metaphysical. Produced in small editions, each book is a work of art in its own right—an experimental and collaborative effort between the artists, writers, editors, designers, and the production team. The design of each book is closely tied to the concepts in the artist’s work—from form and function to typography and materials. All publications are printed and bound in-house at Conveyor Studio, which allows for experimentation and innovation from the concept to the final production of every book.

Today, artist Lisa McCarty interviews co-founder & creative director, Christina Labey.

Follow Conveyor Editions on Instagram: @conveyorstudio

What was the first book you published, and what did you learn from that experience?

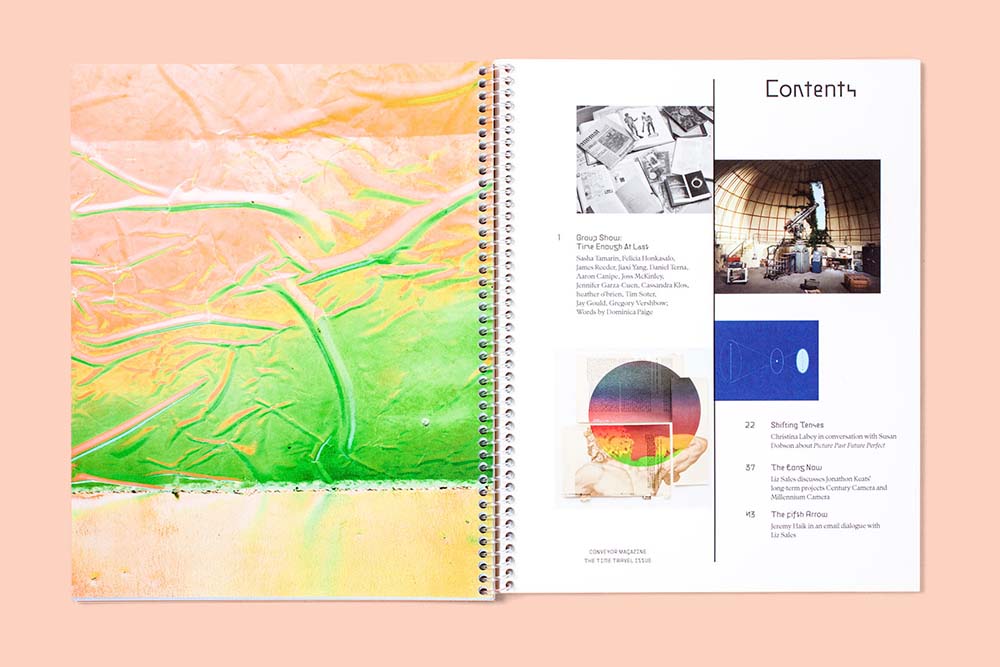

The first project we published was Conveyor magazine, this year marks a decade since it launched. It all began with a call for submissions and an idea that we could build a community through the printed page. We started it with complete naïveté—we’d never even been to an art book fair—but our studio was located within our family book bindery and we had the impulse to make something.

I feel like publishing a magazine is a microcosm of running a publishing label. For each issue, there needs to be an overall vision and consistent tone, yet each article should have a unique voice. Similarly with selecting and editing the photographs, there needs to be a clear aesthetic, but one that doesn’t feel expected or repetitive. Putting it all together, there needs to be a rhythm and pace for the articles that is both organic and interesting. All of these things could be said for how you choose which books to publish.

There is a whole list of practical lessons as well, from building a team of trustworthy fact-checkers and copy-editors to understanding image use laws, public domain, and learning how to work with museums, galleries, and estates for image rights. Managing a team of editors, contributors, and freelancers was probably the most valuable and applicable lesson. We learned about distribution and working with bookstores, we organized public programs—panel discussions, artist talks, book launches, and exhibitions.

One of the most exciting things to come out of this first issue was an invitation to be in the Millennium Magazines exhibition about artists making magazines at MoMA library. Up until then, we’d sort of just been working away in the studio, not really aware of the larger publishing movement, and this was one of the most exciting lessons, that we were actually part of this much larger network of artists who had navigated toward publishing and the printed page as a way to communicate idea, build a community, and collaborate with other artists.

How big is your organization?

Our core publications team is tiny, there are two of us who work consistently on the publications, but we have an incredible community of collaborators and freelancers that make it all possible.

My role as creative director basically means I handle everything from choosing the projects to publish; photo editing, sequencing, and layouts; hiring writers, editors, and designers; and a million other little things that make a book a reality. Once the book is printed, Magali Duzant, our director of public programs, takes over. She coordinates all of the distribution for our books—she is also on our publishing roster which provides unique and lucrative insight for placing our books and creating relationships with bookstores and institutions.

It’s also important to mention that the publishing label is part of Conveyor Studio—we print and bind books for hire—which employs around ten people. I affectionately refer to the studio as our “day job” and our editions as a “labor of love.”

What are the difficulties publishers face?

Speaking on behalf of small publishers, including individual artists who self-publish, I think that navigating distribution and financial viability are the most difficult aspects.

The ability to produce high quality books in small editions makes publishing more accessible than ever, but at the same time, it creates more competition in terms of securing stockists or finding buyers for the books. Smaller print runs also mean higher production costs and therefore smaller margins when you do make sales or work with a bookstore. Honesty, after shipping costs and the wholesale percentage, it’s not uncommon to simply break even with some of our distributors.

What are the difficulties you face as a publisher specifically?

One ongoing challenge is finding the right audience and stockist for each publication.

Though rooted in photography, our projects tend to be more interdisciplinary, which can be a tricky sell for shops that sell more traditional photobooks. We do not publish monographs or surveys, nor do we publish handmade artist books, this in-between space is exciting, but can be hard to place in the larger scene.

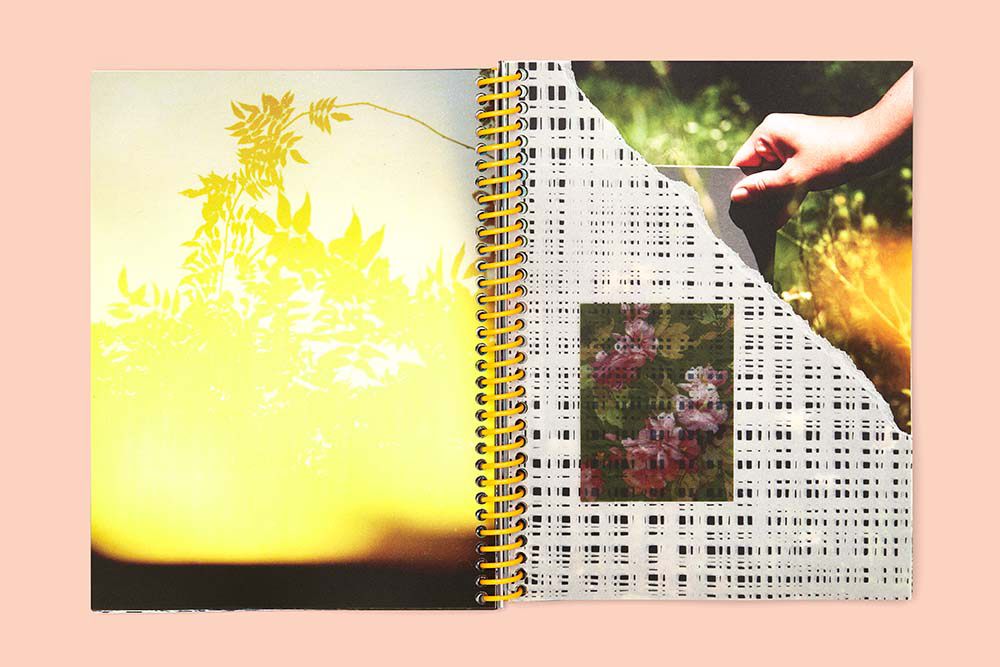

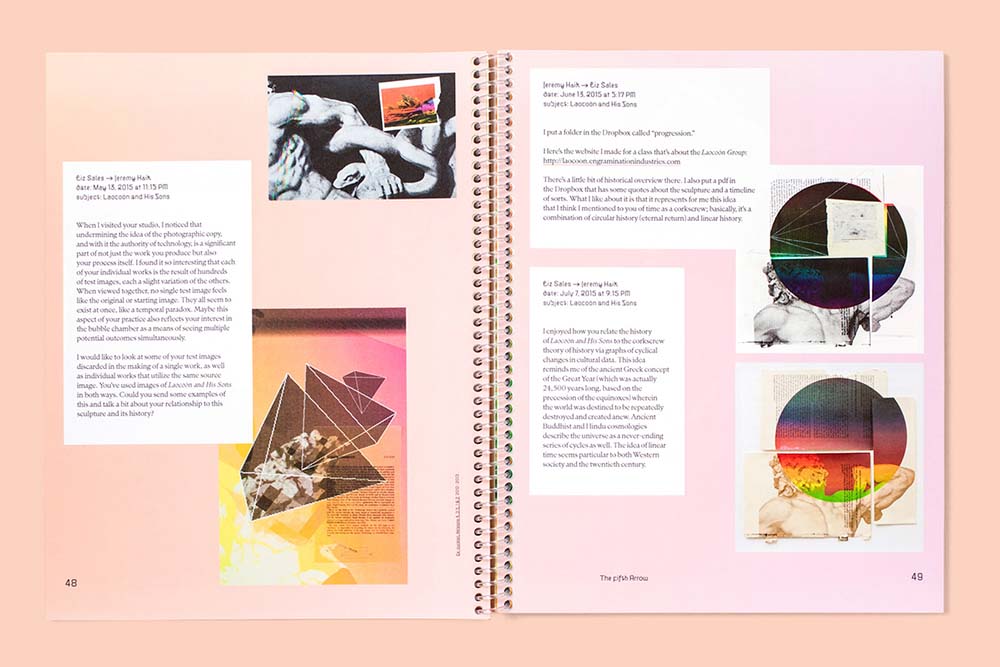

Though we have an overarching aesthetic, we don’t design in a set style. Each book finds its voice and style through its content and the binding style is chosen for its relationship with the content and its functionality. For example, we chose coil binding for the Time Travel issue of Conveyor magazine as a way to explore time as not only linear, but cyclical as well. We’ve also produced several wire bound books to emphasize a book’s relationship to science or user manuals. These styles can seem a bit informal, but we’d argue that they complement the work more than just dropping the content into a standard hardcover book. They also allow for the spreads to lay flat and to insert fold outs, mixed paper stock, and other surprises for the reader.

We also find it challenging to show all of the details in production and materiality when sharing books online, even well executed photographs aren’t the same as experiencing a book in your hand. As a printer and publisher, we pride ourselves on the tactile elements of the book, we bleed a little bit more into the artist book genre, where each book is actually the project and it’s meant to be experienced in that format. So without holding it in your hand, it can be difficult to convey all of the work and ideas that went into it.

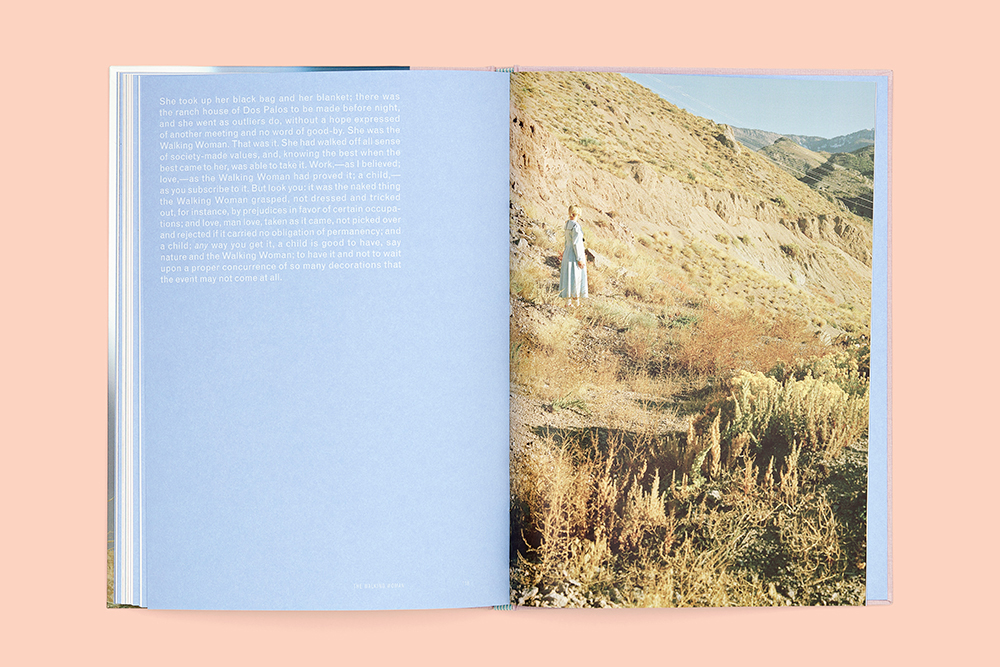

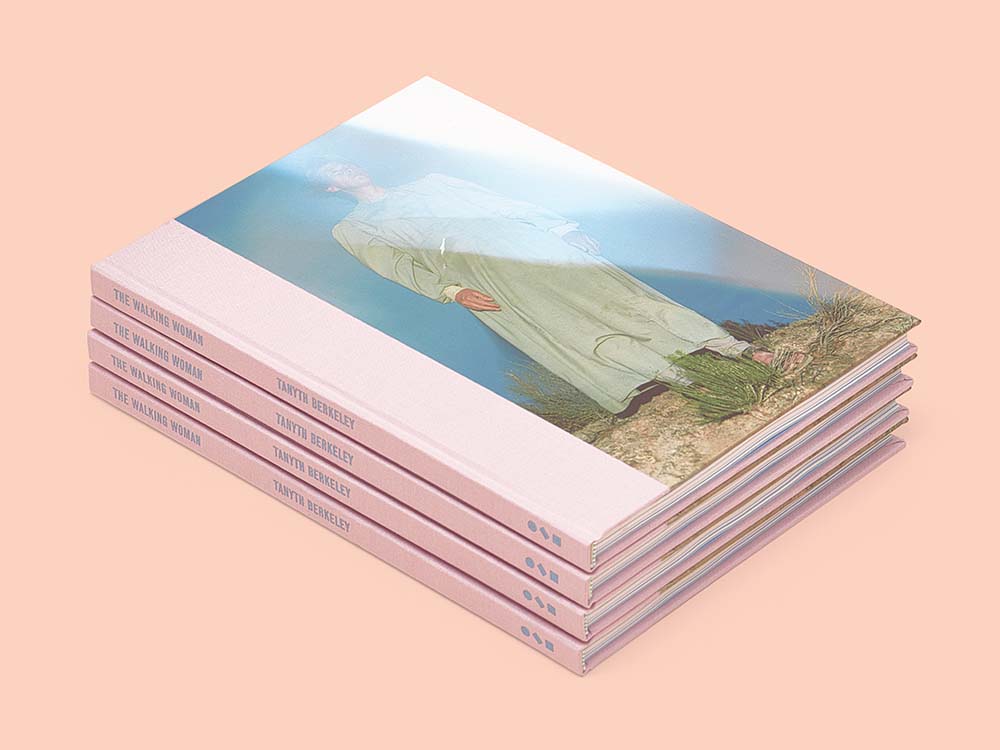

© Conveyor Editions, The Walking Woman by Tanyth Berkeley

Are there any publishing projects that have been particularly meaningful to you?

The Walking Woman by Tanyth Berkeley was a very special project to work on. The book is an extended portrait of two women set against the desert landscape of the American Southwest, the background story is complicated and gives way to countless layers of entangled and complex issues from ecology and feminism to capitalism. It is the kind of project that you need to spend time with and digest the combination of the short story, photographs, and addendum with fragments of emails, phone calls, and conversations with the two women.

The process took several years and many iterations before it felt complete. Tanyth originally came to us as a print client, making a handful of large maquettes to share with galleries and publishers, and over time we fell in love with the work but knew it wasn’t possible to publish in its current edit, so we had to cut about one third of the images.

We went through many rounds of sequencing before it felt right; we debated on how much text to include, ultimately removing a long interview and replacing it with Mary Austin’s short story; and waited until we found a solution for printing the polaroids, when we got white in on our HP Indigo, the process felt right for the feeling we wanted to evoke. It was also the first book we published that included portraiture and the women in the photographs had experienced so much hardship in their lives, so I felt a huge responsibility to tell their story with respect and delicacy.

What upcoming projects are you excited about?

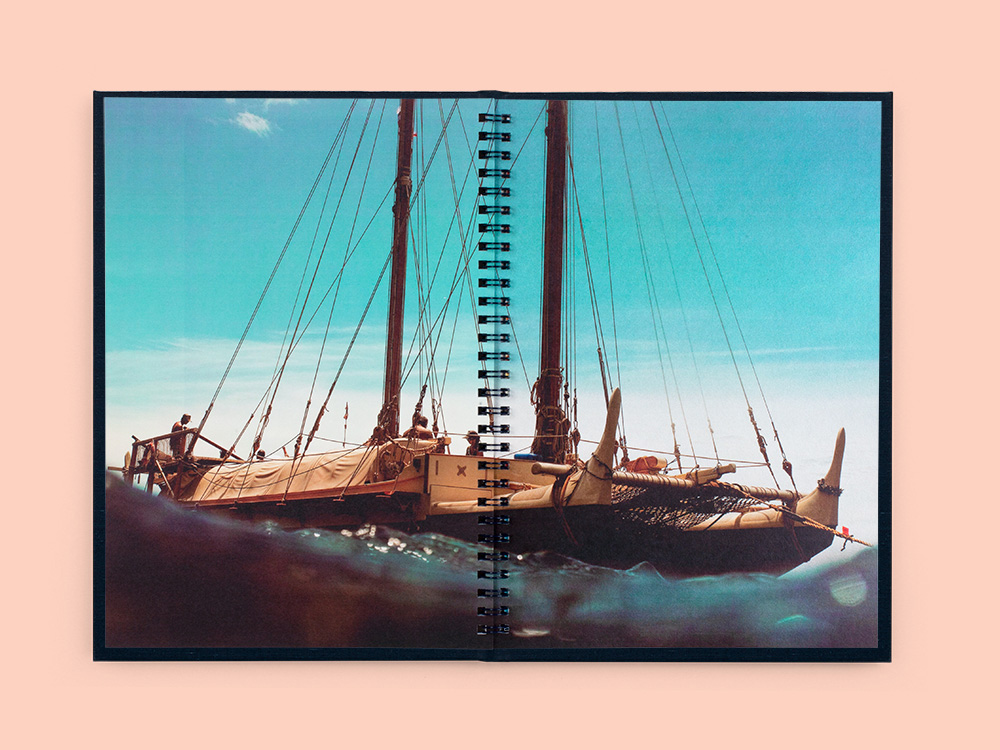

We’ve been working with Brendan George Ko on a project called Moemoeā, which loosely translates to mean a vision or dream. Inspired by his experience as a crew member, the project revolves around traditional voyaging in the Pacific and the Hawaiian cultural renaissance, exploring how the canoe became a tool for connection, cultural empowerment, and our relationship to the natural world. We’ve been working on it for a few years, slowed by the pandemic of course, but can’t wait to launch it next year.

I’m very excited to launch a special edition of I Looked & Looked by Magali Duzant next year in conjunction with the 100 year anniversary of a love letter exchanged between Alfred Stieglitz and Georgia O’Keeffe. The first paperback edition has been sold out for a long time and while we don’t usually do reprints, it felt right to reissue this in a special hardcover version.

We are launching our second project with Peter Happel Christian, titled Same Sum, a photobook that playfully explores observation, chance, and the everyday magic of ordinary life. The binding and design are very fun and experimental, so I’m really looking forward to holding the final book.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Publisher’s Spotlight: Smog PressJanuary 3rd, 2024

-

Publisher’s Spotlight: Kult BooksNovember 10th, 2023

-

Publisher’s Spotlight: ‘cademy BooksJune 25th, 2023

-

Publisher’s Spotlight: Brown Owl PressDecember 10th, 2022

-

Publisher’s Spotlight: DOOKSSeptember 26th, 2022