2022 Hearst Journalism Awards: Noah Riffe: 2022 Finalist Photo Championship

©Noah Riffe, “You need to learn your gay history,” Michael Mehr, 68 of Mountain View, Calif., chuckled as he walks down Castro Street on the way to the San Francisco Lesbian/Gay Freedom Band rehearsal on Sunday, May 22, 2022, in San Francisco. Mehr has been coming to the Castro District since he moved to the Bay Area in 1976 to work a job in the technology industry. The Castro District was one of the first openly gay neighborhoods in the United States and remains one of the most prominent epicenters of queer pride and protest.

This week we are celebrating photographers who have received a 2022 Hearst National Championship Award. Today we focus on National Photojournalism Championship 2022 Finalist in Photo, Noah Riffe, from Penn State and won $1500 plus Best Single Image which is another $1500. The Story Prompt was Individual expression and the Californian Dream.

The Hearst Championships are the culmination of the 2021 – 2022 Journalism Awards Program, which were held in 103 member universities of the Association of Schools of Journalism and Mass Communication with accredited undergraduate journalism programs. From May 20 – 25, 2022, 29 finalists – winners from the 14 monthly competitions – participated in the 62nd annual Hearst Championships in San Francisco where they demonstrated their writing, photography, audio, television and multimedia skills in spot assignments. The assignments were chosen by media professionals who judged the finalists’ work throughout the year and at the Championships.

Noah Riffe is a photojournalist with a passion for telling stories in an authentic and accurate way. He is a native of Seattle, Washington and graduated high school in Dallas, Texas. He started working professionally in 2016 during his sophomore year of high school, covering professional soccer.

Currently, he is studying photojournalism at the Donald P. Bellisario College of Communications at Penn State University and is expecting to graduate in 2023 with a bachelor’s in photojournalism and a minor in political science. His Awards include Finalist | 2021 Hearst Journalism National Championship, Best Single Image | 2021 Hearst Journalism National Championship, 6th Place – Semi-finalist | 2020 Hearst Journalism Competition, 1st Place | 2021 SPJ Region 1 Mark of Excellence Awards – Breaking News, 1st Place | 2020 Press Club of Western Pennsylvania Golden Quill – Sports Photo, and 1st Place | 2020 Student Keystone Press Awards Division I – Photo Story.

Noah is passionate about politics, soccer and good coffee. He is available for freelance assignments: +1 425-221-7287, Noah@NoahRiffePhoto.com

Follow Noah Riffe on Instagram: @NoahRiffePhoto

©Noah Riffe, Marching with a sousaphone slung over his shoulder Michael Mehr plays California, Here I Come! during a band rehearsal at Rikki Streicher Field on Sunday, May 22, 2022, in San Francisco. In 1984, Mehr rented a sousaphone to compete in a radio competition but after three payments the company went bankrupt. “No one came looking for me,” Mehr joked. He still plays the same brass instrument to this day, just now with a few more character scratches and bumps.

Pride and Performance

On a dusty and historic baseball field in the heart of the Castro District in San Francisco, a colorful band marches along the outfield. The sharp snap of a snare, the whisking twirl of a baton and the whomping hums of a sousaphone fill the block as passersby sing along. A free show from the City of San Francisco’s official band.

The San Francisco Lesbian/Gay Freedom Band became the first openly queer music group in the world in 1978. The group formed in protest to the open anti-gay sentiment in the music industry at the time. Original members still playing and remembering reminiscing on their courage.

Throughout its history the group has exemplified an outward expression of queer pride in the Castro community and beyond. 44 years later the band is bigger than ever playing shows all around the United States.

©Noah Riffe, It gets me out of the house,” Michael Mehr shared as he laughed with his friends during band rehearsal at Rikki Streicher Field on Sunday, May 22, 2022, in San Francisco. Mehr joined the band in 1987 with a slight push from his partner, “My lover at the time was pushing for spring cleaning that year and told me that I should use that horn sitting on the living room floor, or he would get rid of it for me.”

Judy Walgren: Hi Noah! Could you start off telling us where you are in school and a little bit about yourself—like where you grew up and how you found photography?

Noah Riffe: For sure! I go to Penn State University in State College, Pennsylvania and I grew up in Seattle, Washington. Both of my parents are artists, and my dad has a fine art degree and worked in video games for the longest time doing production and so I was always around a really creative group growing up. That kind of seeped in and eventually I started just taking pictures in middle school just for fun. I actually found the other day on award that I was given in middle school for some kind of PTSA art competition. I thought it was really cool to see that and see where I’ve gotten to now.

From there we moved to Dallas, Texas where I eventually graduated. I started to do more news stuff and got involved in the broadcast program at the school where I was eventually the producer of and while I was there, I was playing soccer for school and a club program, FC. I didn’t have a lot of friends and I wanted something to occupy my time, so I got an idea to shoot professional soccer. I did a lot of research and learned how to shoot through watching YouTube videos. I would be lying if I said that I didn’t fib a little bit to get my first credential, but I got in! And even though I was shooting on an entry level Nikon camera, I came out with some pretty good frames. I mean looking back, they are fine—but for not having any experience—they are pretty good!

From there, I kept shooting. I had a season long credential, and I knew a digital designer at Topps trading cards. I knew that he looked at sports images all of the time so I asked him if he would just take a look and give me any pointers, because at this point, I didn’t know anyone in the sports photo world outside of the people that I was working with. So, I gave him the photos and he looked over them and ended up sending them to his boss, which led to me getting a contract to do a specific set with just my photos for their digital card trading app.

©Noah Riffe, Streicher Field on Sunday, May 22, 2022, in San Francisco. Mehr has played through history, his first ever trip with the band was to Washington, D.C. to participate in the second March on Washington, a gay rights protest. The group was not welcomed with open arms. While practicing for the march on the National Mall, Capitol Police waited patiently to enforce the expiration of the group’s permit. At 6:00 p.m. on the dot officers mounted on horseback in full riot gear started banging nightsticks on their shields and advancing. “We decided maybe it was a good time to run,” Mehr joked.

Judy: How old were you?

Noah: I think I was 16, because I didn’t have my license yet, and I remember my dad would drive me to these to the soccer game sometimes.

Judy: Were you shooting FC Dallas games?

Noah: Yeah. Anyway, I just wanted to go to all the games and be a part of it somehow so that was my way of doing it. I completed that and my set came out, and I was like this is like something that I want to do. So, I kept with it and switched over and started shooting for free for a blog that was related with the team, so I could just keep shooting. That eventually led to me joining the high school yearbook staff and shooting every sport under the sun. At Sachse High School, I had an amazing journalism teacher.

So, from there, I just started applying to different schools, I applied to every university. I didn’t really know what I was looking for. I had honestly terrible grades in high school, and I was just looking for somewhere to go to college, because I didn’t even think I was going to graduate high school. I was very much not a scholarly student. But I was really proud of myself that I graduated high school and felt like if I can graduate high school, there’s no way I can’t graduate college.

I was looking for a school that had journalism program—so it wasn’t even necessarily photo. I was looking for broadcast programs because that’s what I’d been doing at high school. I looked for places that I wanted to be and programs that I thought were cool. As for Penn State, I had a family friend who works there in the journalism department, and he really pushed me to apply, and I did. I was able to meet with professors, who at the time was Curt Chandler who just died.

©Noah Riffe, Mike Wong, Artistic Director for the San Francisco Lesbian/Gay Freedom Band conducts during a rehearsal at Rikki Streicher Field on Sunday, May 22, 2022, in San Francisco. Wong received the honor of becoming the band’s 12th Artistic Director in January of 2016. During this time the San Francisco Lesbian/Gay Freedom Band has expanded its reach to have chapters nationwide, coming together to play big events like the presidential inauguration.

Judy: I was so sad to hear that. He was such a great person and professor.

Noah: Me, too. I it was tough because he was literally one of the reasons that I’m here. So, him and John Beale I met with a lot, as well as Jamey Perry—and I just pled my case. I was like, “Listen, I’m a really hard worker, I’m not the best student, but I promise you that if I come here and you give me a chance, I will deliver. I will make you proud and make something happen.”

Judy: Well, you delivered on it, didn’t you!

Noah: Marie Hardin, the dean of the college genuinely, genuinely cares about our program and has done more work that was even necessary to make sure that I have been taken care of, and the program is taken care of—she and I have sat down multiple times to talk about the program. I am very excited about the future of it.

©Noah Riffe, 22, 2022, in San Francisco. The San Francisco Lesbian/Gay Freedom Band became the official band of the City of San Francisco in December 2018. The motion by the city council to recognize the group was unanimous and signed into law by the mayor immediately.

Judy: That’s great to hear. Can you talk about your program and how you see the positionality of visuals in the overall way that your journalism school operates?

Noah: So, with the journalism program here, there is a photojournalism option, which is very nice. You are required to take two photojournalism classes, and the way that it’s structured is heavily towards writing. On the photojournalism side, you have to take more writing classes then you have to take photo classes. But I don’t necessarily think that’s bad because you can learn about storytelling through different mediums. I’ve definitely taken a lot from those writing classes and applied it to my photojournalism, especially caption-wise. I was a terrible speller, and I was terrible with grammar—just awful—and having to take those very structured grammar classes and writing stories and all of that made me way better with captions—just being able to wordsmith things that are super complicated, adding on. With my story that I did for Hearst, I definitely wouldn’t have been able to pump out those crazy long captions without having some kind of background in in doing news writing because when I was there shooting, I was thinking about telling a story in this caption would record audio that I could transcribe. I had those processes in my head from those classes. So, I think having to take the writing classes helped me be successful, but I also think it needs to be rebalanced and there needs to be more art-related classes introduced. I blame Tom Brenner for that, who is one of my mentors.

©Noah Riffe, Gary Cozzi plays the bass drum and practices marching during a rehearsal at Rikki Streicher Field on Sunday, May 22, 2022, in San Francisco. After a performance that morning in The Castro District the band began practicing for the upcoming San Francisco Pride Parade.

Judy: Then okay so, then the writing part has helped you right, but like what about the writers doing the visual work?

Noah: Definitely, I mean I think everyone’s a photographer now—we all have phones, we all have different mediums to quickly take photos. So naturally, there’s a lot more people thinking visually nowadays. Does that mean that they’re taking the best photo? Probably not. But I think there’s always work to be done, I think that it’s hard to understand what someone does without being there and understanding it? That’s also part of why photojournalism is important—because it shows you what you can’t see. I’ve worked in multiple newsrooms and I’ve worked at companies that are not necessarily journalism, but I was doing photo stuff and I would say that they are way more literate of photography and respecting of it. And they don’t want to run their story with a bad photo anymore, because they’re not going to get clicks. And you know it’s sad but true—click driven content is what’s important to a lot of newsrooms

©Noah Riffe, Listening from the shade Andrea Nguyen, San Francisco Lesbian/Gay Freedom Band’s archivist, sketches while the band practices marching during a rehearsal at Rikki Streicher Field on Sunday, May 22, 2022, in San Francisco. The group’s groundbreaking history has been immaculately preserved through the work of its members amassing an archive of costumes, fliers and photos.

Judy: Tell us about going to San Francisco. How did you find your story, then what was your story and how did it go?

Noah: Yeah, so I’ll kind of start from when I got the call that I was going to actually be in Hearst. I was sitting at my kitchen table in Seattle—I was back visiting my parents and I just had a bag of clothes with me. When I get this phone call from my professor John Beale and he says, “Hey did you check your email?” I say, “Its summer. I’m not going into the Outlook email. I’m sorry, John, you’re going to have to text me. And he goes, “You’re in the Hearst final!” and I’m like, “Huh?” I was very much just caught off guard literally and figuratively, I had no gear, I was in Seattle, which honestly for travel made it much easier, but still. Penn State was very gracious to ship me out all my gear. My girlfriend packed it in my Pelican case, and they sent it out to me. I appreciate them so.

Judy: What were you doing in Seattle?

Noah: I was back visiting my parents because I have a summer internship—at the Lincoln Star Journal in Lincoln, Nebraska. It’s a six month internship and it paid—really well, actually.

©Noah Riffe, Tossing up a light up baton Chi Energy, the San Francisco Lesbian/Gay Freedom Band’s twirler, warms up during a rehearsal at Rikki Streicher Field on Sunday, May 22, 2022, in San Francisco. Retired from a life working in technology Chi performs all over San Francisco twirling.

©Noah Riffe, Leading the band, Chi Energy, the band’s twirler, practices his marching with the band during a rehearsal at Rikki Streicher Field on Sunday, May 22, 2022, in San Francisco. Chi has been marching and leading the band for years and considers the group some of his good friends getting to spend time with them every week.

Judy: Ok, back to Hearst. What happened next?

Noah: I got my ticket down to San Francisco. I’ve never been to San Francisco, but I’ve been to California many times growing up on the west coast. I was pretty nervous coming in, I didn’t have a story nailed down before I got there. They gave us a prompt beforehand—to shoot one story about in a post pandemic America, show individual expression and the California Dream. I had ideas written down in my notebook, but I didn’t have anything solidly planned.

So, I get there, and I meet one of the contestants from University of Kentucky Jack and we chatted, and I was like, “I really don’t want this to be a super competitive environment because for one—someone’s going to win and we’re all so talented. I’d rather be close to all these people, and you know walk away with a group of friends, then be super competitive. So I was like, “Hey let’s go let’s go get dinner!” So that started it off really nicely. Jack and I went out and ate fried chicken sandwiches and hung out. I thought at least I’m going to meet some people here; I’m going to network. I’m going to connect and it’s going to be good. That doesn’t mean that I wasn’t nervous the rest of the time, but it definitely was like a wave of that was anxiety gone.

And then, then the first day, I had four different stories lined up. I did a lot of reading, and I got these big ass sticky notes and started writing down anything relating to the words I was thinking – California, individual reveal and resolve, and stuff like that. The first story fell apart – it was about a couple that ran a lighthouse, but they backed out. Then there is the very first transgender bishop, but they were out of town, there is an indigenous land trust and they invested in bringing back native plants and connecting with their culture—it was visually great, but it wasn’t feasible because they weren’t doing anything that weekend. Then there was a queer skateboarding group, and I couldn’t get into contact with them. I was going to a zine fair, and I couldn’t find it. It just seemed like one thing after another. I am already of out my element. I don’t like dropping into a place and not knowing anyone. I was in one of those moments where I was just sitting in a parklet, in the garden in the heat with my notebook thinking, “Don’t break down, you got this. Something’s going to happen. Something’s going to come.” It was just one of those moments when I was broken down to the bottom. It was literally the most challenging moment of my career. I decided to call it a day.

The next day, I decided to go to the Castro to hang out and just talk to people—there’s got to be a story there. And I get there and it’s Harvey Milk Day! There was an event going on and the first people to perform Is this queer marching band, and it’s awesome. So, I saw someone who I thought was going to be really friendly – he played the sousaphone. I asked, “Can I make a portrait of you?” And he says, “Oh, of course.” So we did the portrait and we just started chatting and he said, “I’m going to go to lunch,” and I asked, “Do you mind if I join you?” And he said, “Of course, come on down.” And so, we went and ate at his favorite restaurant in the Castro and just chatted. It was great. And I was able to come and visit them at their rehearsal. And that was my story – It was about the San Francisco which was great.

And that was my story—it was about the San Francisco Lesbian/Gay Freedom Band.

©Noah Riffe, Surrounded by his hand made costumes, rhinestones, vinyl and feathers, Chi Energy sews on a button to his San Francisco Pride Parade outfit in his home in the Castro District on Monday, May 23, 2022 in San Francisco.

Judy: At the end of the day, Noah, you delivered! You got your story. Overall, do you think you can take this experience and use it somehow?

Noah: It was a grind, it was tough. But it put the wind back in my sails as a photographer who was kind of burned out from the pandemic and just school, and all of that. And even more than that, the friends that I made there—like we still text all the time. We are super close.

Judy: I am so impressed! Thank you so much for your time and congratulations!

©Noah Riffe, Chi Energy shows photos from his Twirling World Championship win at his home in the Castro District on Monday, May 23, 2022, in San Francisco. Chi has won at every level of competition as a twirler and as a coach. “I have won over 100 trophies,” Chi shared. Growing up in a very religious and conservative household he chose twirling for the competition and expression. “My parents wouldn’t even let me keep the trophies because they said they were idols,” Chi shared

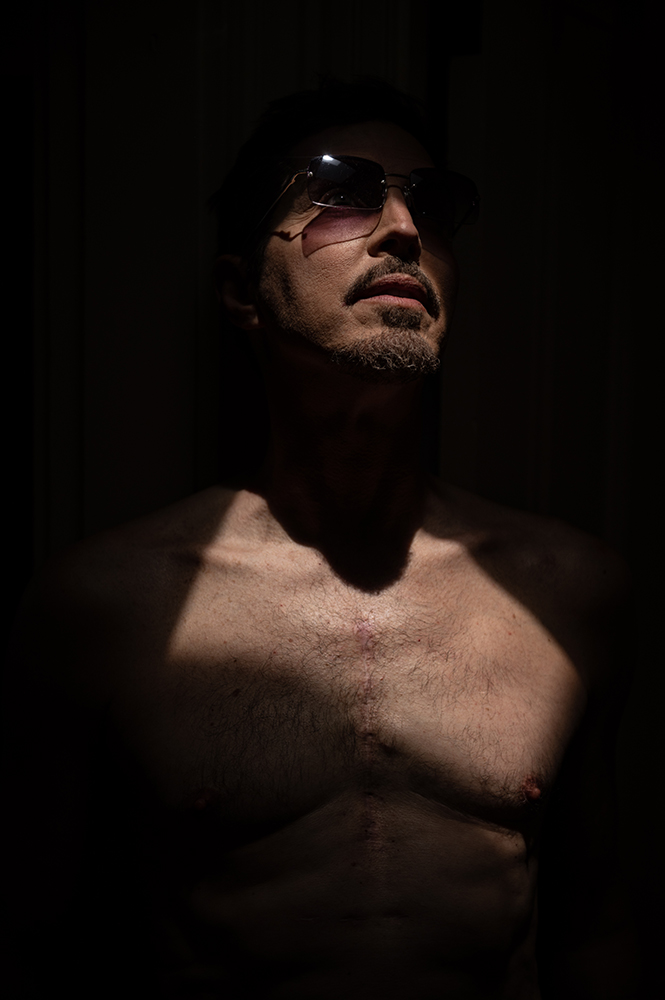

©Noah Riffe, Castro District on Monday, May 23, 2022, in San Francisco. The surgery required a heart bypass machine and breathing machine making him unable to move for months after the procedure. At 50 after being active all his life, he lost most of his muscle and cut his weight by over 30 pounds. Chi now wears padded undershirts, so people won’t notice his change. “I thought I would never be able to perform again. Leading the band in this year’s San Francisco Pride Parade has become my goal,” Chi said softly.

MSU J-School Associate Director and Professor of Practice Judy Walgren is an award-winning photographic artist, teacher, photo editor, curator and writer. received her MFA in Visual Art from the Vermont College of Fine Art in January 2016 where she began her exploration into the disruption of historic visual archives. From 2010 to 2015, she was the Director of Photography at the San Francisco Chronicle, where she managed a staff of visual content producers, photo editors and pre-press imagers for print and digital platforms. During her tenure at the Chronicle, her team won multiple Emmy Awards for their multimedia pieces and they earned Photo Editing Team of the Year from Best of Photojournalism. She has also worked for the Denver Post, The Rocky Mountain News and the Dallas Morning News. Walgren received a Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting with a team from the Morning New for their series dealing with violent human rights against women. She lives in San Francisco.

Follow Judy Walgren on Instagram: @judywalgren

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Yorgos Efthymiadis: The James and Audrey Foster Prize 2025 WinnerJanuary 2nd, 2026

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)October 1st, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: George Nobechi (2021) and Ingrid Weyland (2022)September 30th, 2025

![In the early morning of Sunday, September 15, 1963, four members of the United Klans of AmericaÑThomas Edwin Blanton Jr.,Herman Frank Cash, Robert Edward Chambliss, and Bobby Frank CherryÑplanted a minimum of 15 sticks of dynamite with a time delay under the steps of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, close to the basement.

At approximately 10:22 a.m., an anonymous man phoned the 16th Street Baptist Church. The call was answered by the acting Sunday School secretary: a 14-year-old girl named Carolyn Maull. To Maull, the anonymous caller simply said the words, "Three minutes", before terminating the call. Less than one minute later, the bomb exploded as five children were present within the basement assembly, changing into their choir robes in preparation for a sermon entitled "A Love That Forgives". According to one survivor, the explosion shook the entire building and propelled the girls' bodies through the air "like rag dolls".

The explosion blew a hole measuring seven feet in diameter in the church's rear wall, and a crater five feet wide and two feet deep in the ladies' basement lounge, destroying the rear steps to the church and blowing one passing motorist out of his car. Several other cars parked near the site of the blast were destroyed, and windows of properties located more than two blocks from the church were also damaged. All but one of the church's stained-glass windows were destroyed in the explosion. The sole stained-glass window largely undamaged in the explosion depicted Christ leading a group of young children.

Hundreds of individuals, some of them lightly wounded, converged on the church to search the debris for survivors as police erected barricades around the church and several outraged men scuffled with police. An estimated 2,000 black people, many of them hysterical, converged on the scene in the hours following the explosion as the church's pastor, the Reverend John Cross Jr., attempted to placate the crowd by loudly reciting the 23rd Psalm through a bullhorn. One individual who converged on the scene to help search for survivors, Charles Vann, later recollected that he had observed a solitary white man whom he recognized as Robert Edward Chambliss (a known member of the Ku Klux Klan) standing alone and motionless at a barricade. According to Vann's later testimony, Chambliss was standing "looking down toward the church, like a firebug watching his fire".

Four girls, Addie Mae Collins (age 14, born April 18, 1949), Carol Denise McNair (age 11, born November 17, 1951), Carole Robertson (age 14, born April 24, 1949), and Cynthia Wesley (age 14, born April 30, 1949), were killed in the attack. The explosion was so intense that one of the girls' bodies was decapitated and so badly mutilated in the explosion that her body could only be identified through her clothing and a ring, whereas another victim had been killed by a piece of mortar embedded in her skull. The then-pastor of the church, the Reverend John Cross, would recollect in 2001 that the girls' bodies were found "stacked on top of each other, clung together". All four girls were pronounced dead on arrival at the Hillman Emergency Clinic.

More than 20 additional people were injured in the explosion, one of whom was Addie Mae's younger sister, 12-year-old Sarah Collins, who had 21 pieces of glass embedded in her face and was blinded in one eye. In her later recollections of the bombing, Collins would recall that in the moments immediately before the explosion, she had observed her sister, Addie, tying her dress sash.[33] Another sister of Addie Mae Collins, 16-year-old Junie Collins, would later recall that shortly before the explosion, she had been sitting in the basement of the church reading the Bible and had observed Addie Mae Collins tying the dress sash of Carol Denise McNair before she had herself returned upstairs to the ground floor of the church.](http://lenscratch.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/001-16th-Street-Baptist-Church-Easter-v2-14x14-150x150.jpg)