Portrait Week: Chris Bartlett: Iraqi Detainees: Ordinary People, Extraordinary Ordeals

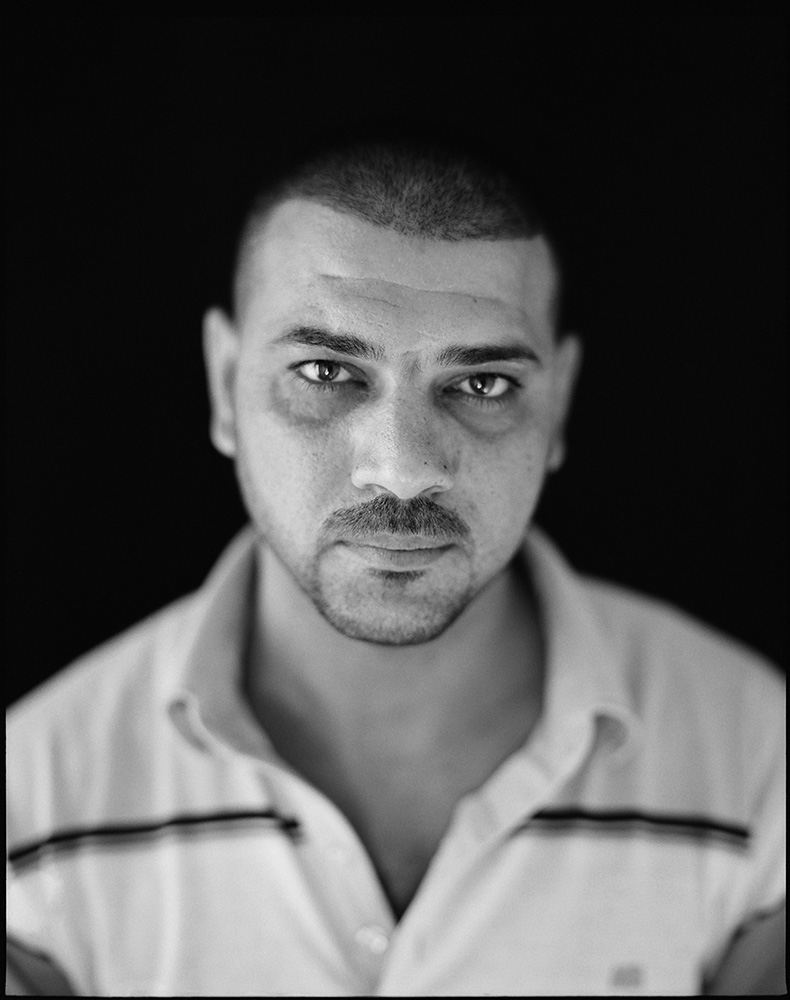

At the time of this portrait Burham was single and lived with his family. He had served in the Iraqi military. “They interrogated me for 2 to 3 times a day. I started not recognizing night from day.” He passed out at each interrogation. He does not remember how long he was in that cell, but he thinks it was a month. He was then transferred to another location. “First they got me naked, and they tied my hands to the door. My detention lasted six months. I was always naked, always tied to the door. They brought the dogs to us.” Just before his release, they told him he was falsely arrested. “I started to have severe depression. I started sitting by myself alone. I became not normal. My family understands this.”

“Anyone who was detained the (Iraqi) military has our names and we have to check in weekly. The slightest thing that happens in Baghdad they have to bring in people who were detained. Anything wrong, any kind of explosion, we will be the first to be accused. I got kidney failure because of being detained. I didn’t have any money so I had to borrow from friends and sell my car to get a new kidney.

We suffered so much for no reason, and year and a half of my life being tortured, humiliated, and beaten. What’s good about that? The Americans are gone and now I am blacklisted by my own people.”

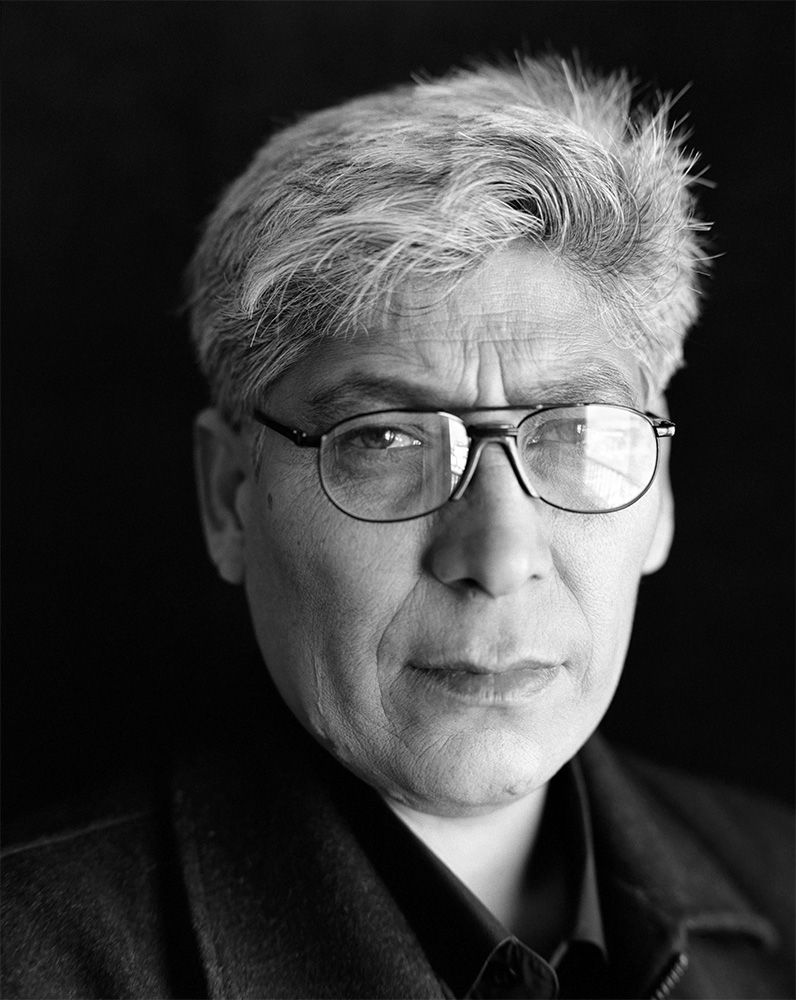

I recently met Chris Bartlett and his work at the Los Angeles Center of Photography’s Exposure Reviews. His portraits of Iraqis who had lived through horrific torture and abuse were profound. He tells his story here:

This is a self-funded portrait project of ordinary and innocent Iraqis who were detained, tortured, and abused by the U.S. military and their subcontractors after the United States’ invasion of Iraq. In the first few years of the conflict, which began 20 years ago this March, tens of thousands of individuals were detained by the coalition forces. Most of those detained were innocent and it is not an exaggeration to say that the vast majority of Iraqis picked up were harassed, mistreated, abused, or tortured in some way. How you describe their treatment derives in part from how you define torture. Is it, as the government defined it, only torture when it leads to “death, organ failure, or permanent damage”? Is waterboarding torture? Is “Enhanced Interrogation” different than torture? If one is stripped naked, chained to a door, locked in a darkened room for 23 hours a day, beaten at regular intervals, threatened with dogs for weeks or months on end with one bathroom break and one meal a day – is that considered torture? Our government didn’t define it as so. If your son or daughter happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time while traveling abroad, and they were picked up and treated this way, with no charges filed and no notice to family given, would you feel that they had been tortured? If the country that they were visiting was on high terror alert would it justify that treatment? The individuals shown in these portraits are Iraqis who were detained under the auspices of the United States military and its surrogates. All were tortured and abused for months into years and all were released without charges and often without explanation. The portraits were taken in the spring of 2006 in Amman, Jordan and the summer of 2007 in Istanbul, Turkey.

The issue of abuse came to light with the discovery of the soldiers’ private photo sharing of the graphic interrogation pictures with their “point and shoot” digital cameras. And while the discovery of the photos brought widespread awareness of the injustice, the imagery also further dehumanized the victims. The camera had become an instrument of torture and with few exceptions the only images the world had seen of the victims were those taken by the victimizers.

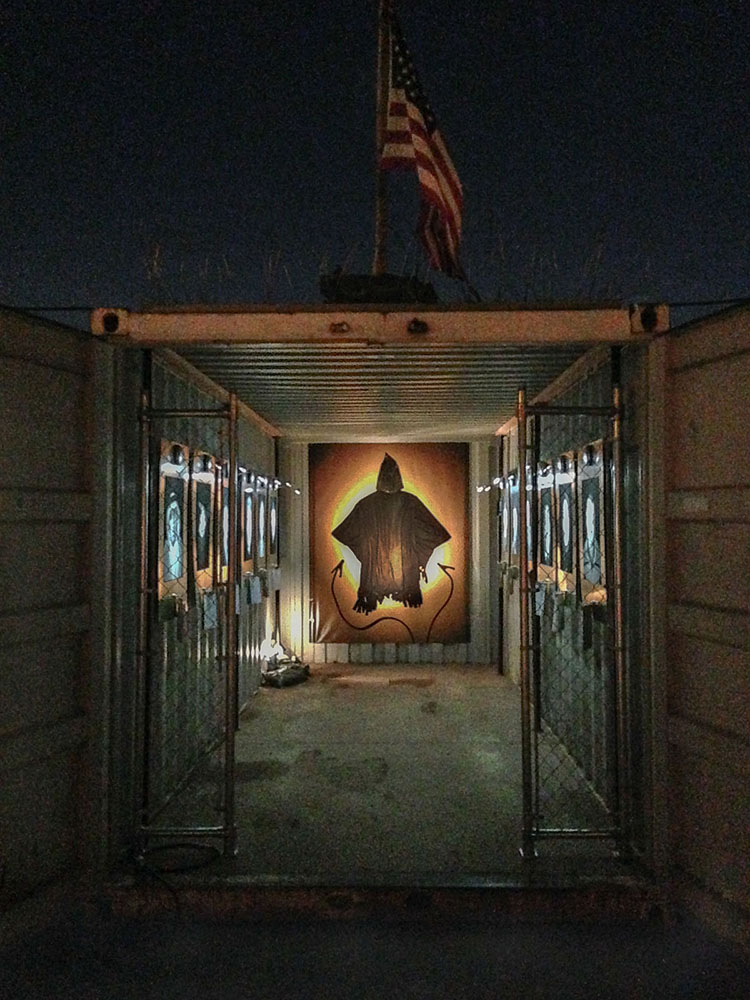

I was invited to participate by the lawyer Susan Burke, who at the time, was the lead attorney representing the Iraqis in class action lawsuits against the military subcontractors. (The military cannot be sued directly.) There is still one case working through the courts: Al Shimari, et al. v. CACI that was filed in June, 2008 by the Center For Constitutional Rights. The project was shown at the Open Society Foundations’ Moving Walls exhibition in 2008. In 2014 it was reinterpreted as a container installation for Photoville in NYC. It subsequently went to Houston Fotofest, and the Hamburg Triennial. The project was covered by the BBC, NPR, Canadian Public Radio, Al Jazeera among others.

In 2019, 15 years after the detainee abuse came to light, I crowd-funded a followup. I found 4 of the subjects from 2006-7 and arranged for them to come to Istanbul. I made updated portraits and recorded video interviews. The takeaway of that experience was that the pain, anxiety, and trauma felt by the victims was as acute in 2019 as it was when they were released 15 years earlier. This is where this project crosses into the larger issue of the legacy of trauma. This followup chapter has yet to be exhibited.

As we enter 2023 it is nearly 20 years since the detainee abuse was first reported. Most Americans are not aware of the extent of the practice of torture in the early years of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. It was designed, planned and implemented from the highest levels of our government. The techniques were researched, recorded, and became routine for detainee treatment. The use of torture seeped into our national consciousness and was further normalized through popular culture: the show 24 and the film Zero Dark Thirty being two of the most prominent examples. My goal from the outset has been for Americans to see the faces of the innocent victims of this abuse and for future leaders to understand the moral and geopolitical ramifications of the choice to torture. If there ever was such a thing as American exceptionalism, it ended here.

Chris Bartlett is a photographer living in the Hudson Valley, NY whose decades long personal practice includes portraiture, documentary/social justice, street photography, conceptual still life, landscape and fine art. His social justice projects have focused on Iraqi former detainees, Burmese dissidents and former political prisoners, and U.S. military assault victims. His portraits have been used for advocacy by the United Nations in Geneva, the Center for Constitutional Rights, Amnesty International, Bloomberg Philanthropies, and Protect Our Defenders. He has exhibited at Open Society Foundation’s Moving Walls, Houston Fotofest, Hamburg Triennial, and been interviewed by the BBC, NPR, Canadian Public Radio, and Al Jazeera among others. Chris is also a commercial still life photographer in New York City.

Follow Chris Bartlett on Instagram: @chrisbartlettstudio_archive

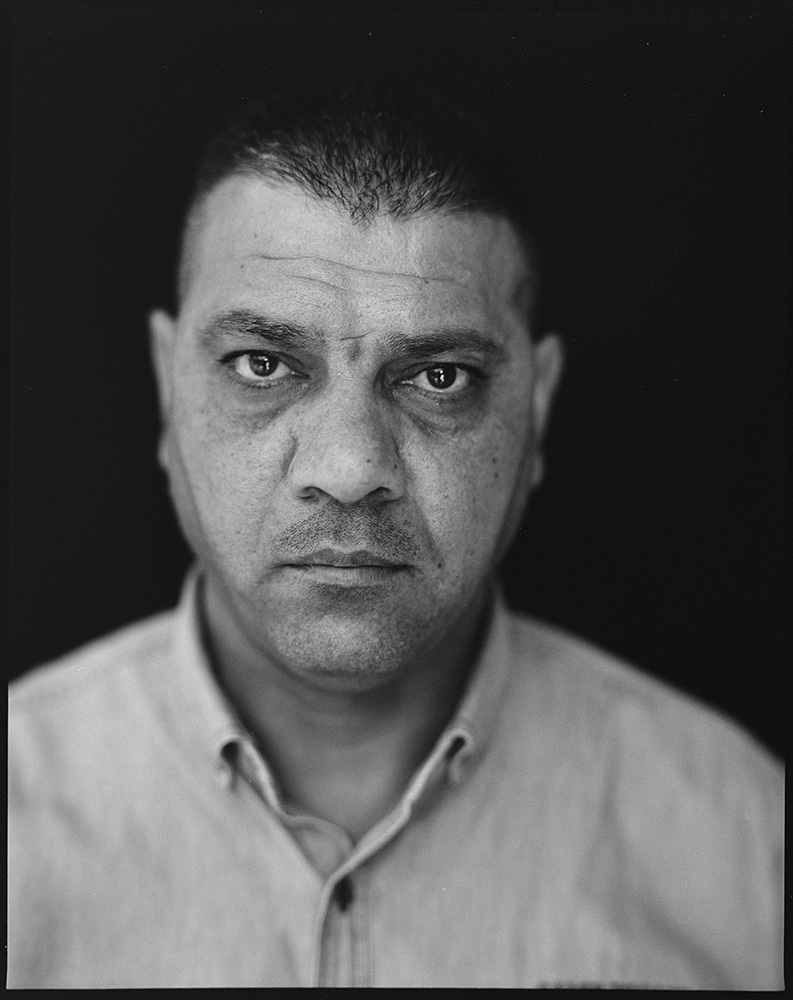

He was a teacher in an Islamic institution and president of the human rights section of the Association of Islamic Scholars in Baghdad. One of his five children, “a student, first in his class”, was killed. “The soldiers broke my teeth with guns, they hit me with wooden sticks, and I passed out. At the release section an officer asked, ‘have you been tortured?’. Some prisoners had told us that they said ‘yes’ and were sent back to prison. We all said ‘no’ and signed.”

“From the freezing camp torture, the black boxes in the airport, the mistreatment, the same food for months and years. The inhumane treatment all resulted in a constant depression, fatigue, loss of memory, sexual dysfunction. They hit me more than once on my head, broke my teeth. Honestly, for years I have suffered all this pain. The U.S. needs to know that there is a story for every detainee taken from their homes to Bucca camp – thousands of stories of suffering.

How is it possible for a country like America that has many institutions for human rights to dismiss the case to investigate the actions of the interrogators and translators, it’s unfair to us victims. And it doesn’t really represent the morals of the American people or their intentions. The way we are denied (justice) like that is something incredible.”

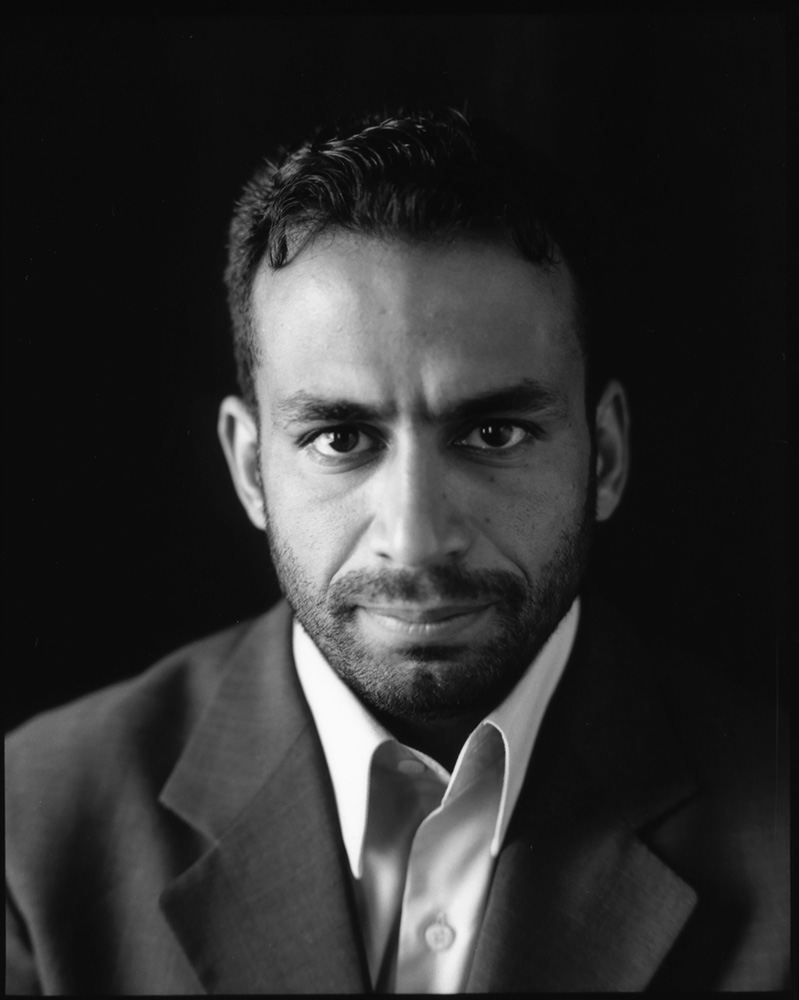

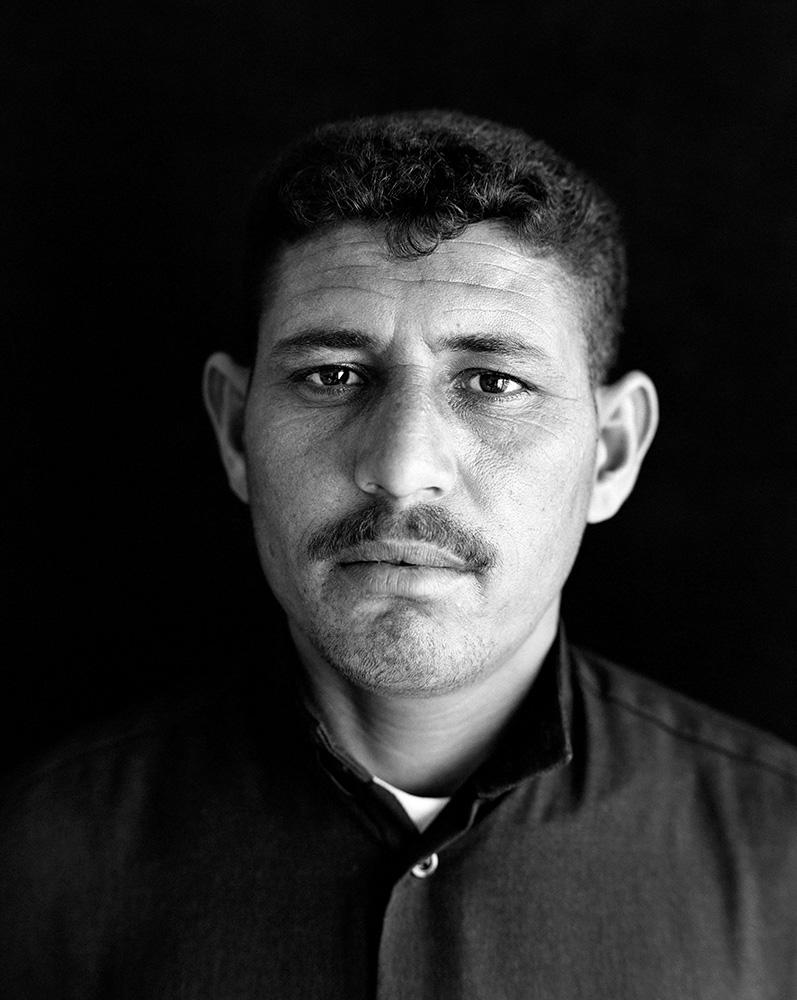

Married, taxi driver. “The only honest job in Iraq after the invasion. Before the invasion I was praying to God that the Americans would come to free us from Saddam. We are so disappointed because what the Americans did, the injustice, it was worse than what Saddam was doing.”

After I photographed Firas in 2007, he was detained again by the Iraqi forces for 4 more months. “I have aches everywhere in my body, my emotional state is zero. Since I have been arrested I have urinary incontinence until this moment. I feel shameful to talk about it, even in front of my wife. I have a continuous bad headache and have bad pain in both of my ears because they would push my head inside the water.

I was detained for all that period of time for nothing, that’s what makes me deeply depressed. I want to prove to my family that I’m innocent. That could at least help me in front of my family members, my wife, my children. I could take the decision from the American court, show it to the people in the whole world and tell them, see I got my rights back, I’m innocent! If a member of the American government read my case, would they ever be ok seeing his son or daughter to go through what I’ve been through? I hope one day, been hoping since 2006 until now, that this nightmare would disappear.”

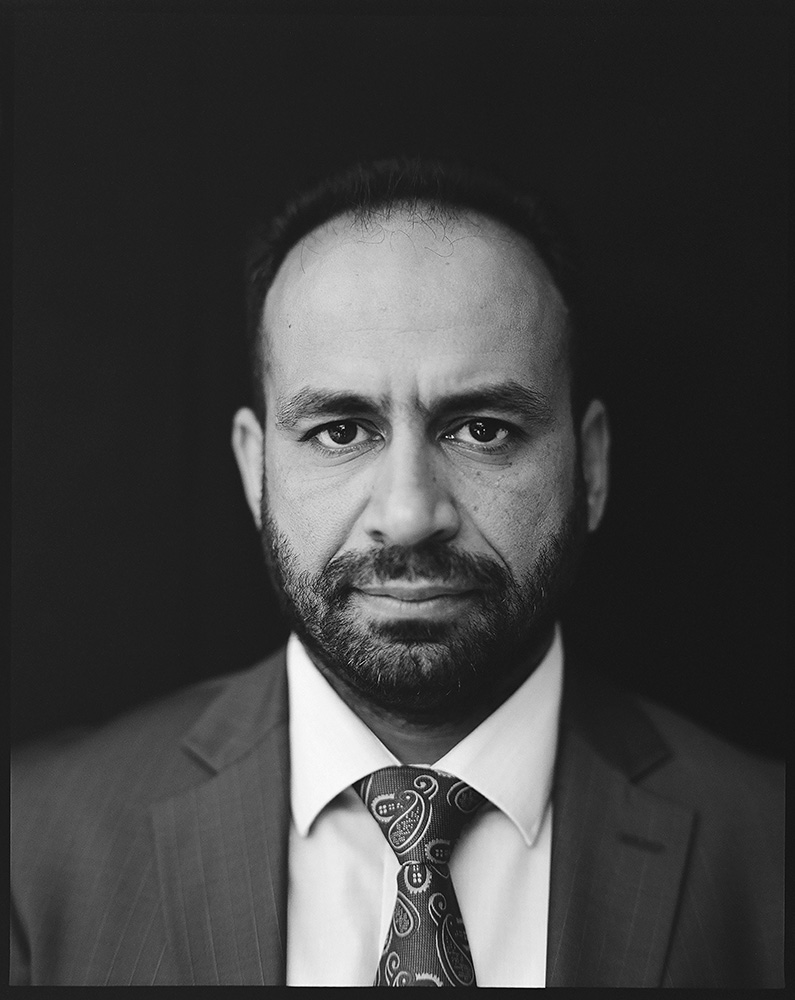

“When they broke in, they hit me with a weapon and broke my rib. I remained handcuffed behind my back for 16 days. My shoulders were swollen with blood. They put us in black boxes about a meter high, handcuffed and lying down. While I was in the box every 20 to 30 minutes someone would kick the door really hard.” When he fainted, they took him out, gave him an IV, and put him back in the box. This happened every three days.

“The second arrest they placed me in a coffin for 16 days. It was a wooden box and they would kick it every 10-15 minutes while I was inside, it felt like an explosion. When they let me out of the box I had worms inside of my skin. When I told them about the worms, they came dressed as bee keepers, picked me up and threw me in the yard naked in front of 600 prisoners, and kept me in the sun.

I have night terrors, which wakes me up at night. Anything disturbs my sleep and it’s a real issue to a point where I have to sleep by myself at home because I’d wake up panicking even if I heard the sound of my own clothes rustling. I know that they let us go but that’s not enough, I’m going to tell my children what happened to me and they will tell their children. It’s going to be known for them that the Americans had bad intentions and never corrected them.”

At the time of the portrait she was divorced with seven children and an accountant. “They put me in a room and they put my son in a cage in front of me.” The man said to her, “confess that you know terrorists or I will send you to a place where they will rape you. They will do things to you that you could never imagine.”

He was the “other” hooded man, photographed at Abu Ghraib while standing on a cardboard box holding electric wires. They forced him to lie on the ground, loudspeakers blasting music into his ears. The ordeal lasted only a day, “but it felt like two years.” They beat him regularly, and on three occasions subjected him to electric shock treatments. “It feels like your eyes will explode.” A soldier said, “we are doing what the interrogators want.

They want us to make your life very difficult so you will answer questions.” After his release, he founded the Association of Victims of Americans Occupation Prisons in Baghdad. “There is not one person in prison in Iraq who has not been subjected to some kind of abuse.”

He was married with five children, a farmer and former police officer. “They came at night. My wife wanted to open the door to my room but the man hit her and put a machine gun to her neck, they stole everything.” He was put in a cage a meter wide and a meter high. “I asked why they are doing this, so they hit me.”

One of ten siblings, he raised sheep, cattle, and goats for sale at the market. He had never been arrested before, never had any dealings with the authorities. They came at night. The soldiers knocked on the door. His mother, carrying her six year old daughter, went to the door. A bomb, “with nails in it”, blew the door open killing his mother and sister. They put him in a vehicle covering his head with a piece of clothing stained with his mother’s blood. He was released after three months at Abu Ghraib. He was never charged or accused of doing anything wrong.

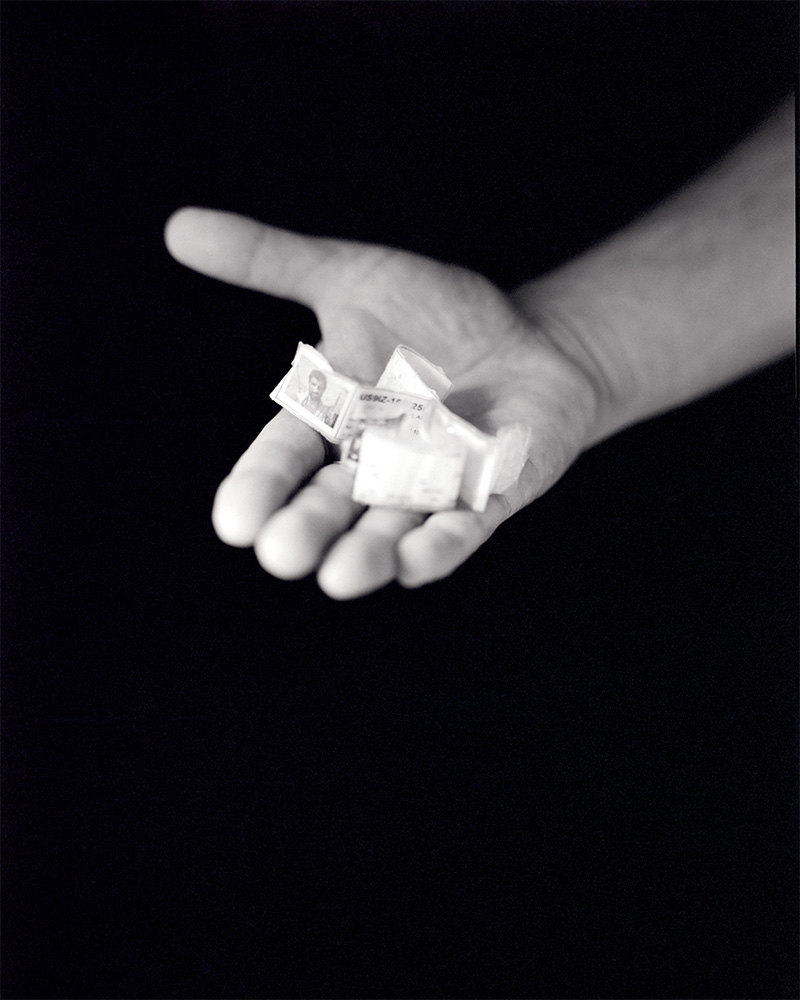

He is holding his prison identification bracelet. He did not want to show his face. At the time of this portrait he was engaged to be married and he sold cars for his family. During his detention he was forced to lie down in urine and feces. He couldn’t breathe because of the smell. His feet and shoulders bled, and the urine exacerbated the pain from the wounds. “They brought a rope and put it around my neck. It was a rope made for dogs, made from leather. They hit me on my left side and then in the groin and after that I fainted. When someone was pissing on me, they stopped kicking. After that, another one kicked me, and I fainted again.”

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Tom Zimberoff: The White Fence and more..March 2nd, 2026

-

The 2026 Black and White Portraits Lenscratch ExhibitionMarch 1st, 2026

-

The 2026 Black and White Portraits Lenscratch Exhibition | Part IIMarch 1st, 2026