Photographers on Photographers: Chloe Dichter in conversation with Meggan Gould

Photographers on Photographers is our annual August effort where we ask photographers (including the Top 25 Winners of the 2023 Student Prize Awards) to interview an artist or mentor that has impacted or inspired their practice.

When I started my MFA studies at the University of New Mexico in 2022 I had the pleasure of meeting and working closely with Meggan Gould. A photographer and multidisciplinarian, Meg’s work constantly bends the rules of photography in clever, humorous, and dextrous ways that I admire greatly. I have had the chance to get to know her in several capacities during my time at UNM and I was grateful she wanted to converse with me for fifty-seven minutes about her life, career, and travels. When I was asked to contribute to Lenscratch’s Photographers on Photographers feature, I knew there was only one person with whom I wanted to sit down and talk shop. I deeply respect her as a human and artist, and through working with her I am able to embrace my own joy of making.

Meggan Gould lives and works in the mountains outside of Albuquerque, New Mexico, where she is a Professor of Art at the University of New Mexico. She received an MFA from the University of Massachusetts – Dartmouth, and a BA from the

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her work has been exhibited widely in the United States and internationally, and is included in many private and corporate collections, as well as public collections including the DeCordova Museum, the Preus Museum, the New Mexico Museum of Art, Light Work, and the University of New Mexico Art Museum. Her multifaceted practice uses photography, writing, drawing, sculpture, and installation in an open-ended dissection of vision and photographic tools.

Instagram: @megganlgould

Chloe Dichter: What did you have for breakfast today?

Meggan Gould: A bowl of fruit with Greek yogurt that I make. It’s delicious.

CD: You make your own yogurt?

MG: I have for years. Years and years. Once you start making yogurt it’s really hard to

buy yogurt in plastic containers in terms of ease, finances, and waste of plastic.

CD: Can you get, like, botulism or something?

MG: No, it’s pretty safe. Two thumbs up for homemade yogurt.

CD: Okay, I feel like I got to know a little bit more about you during the Light and Writing class I took with you last semester, and before that it’s not that you were an enigma to me, but I didn’t know a lot about your past. I wanted to know if there’s a specific moment that you knew that you wanted to pursue photography?

MG: I don’t think that clarity usually happens quite that directly with one project or one image. I made lots of weird choices after college in little fits and starts, shall we say. I first started taking photography at RISD in this continuing-ed program, while I was working a day job and taking night classes. I really liked it, but I didn’t take anything seriously. Nothing felt like it was the future. Then I said, “I guess I take it seriously enough. I’ll go to France to study.” But again, was it like capital F future? Not necessarily. It just sounded really fun to go to France to do photography for a year. So I think that was the level of investment I was giving anything. This is fun, and I am doing it for now, and I don’t need to make major life decisions. I was actually a little cautious about considering myself an artist until that year in France. I had never studied art or taken any art classes, no art history. Art was this big mystery to me. For me, it was the commitment I was scared of. Of being a capital-A Artist. I think it was when I studied in France and then I stayed there to teach black and white photography at the school, somewhere in there I said “Oh, I guess this is for real.”

CD: I feel like a lot of people have tension around claiming the title of being an artist, especially photographers. What was that like for you?

MG: My program in Paris was very commercially-oriented. We learned a lot about studio lighting, studio cameras, and another big chunk was photojournalism. Then there was a small chunk that was the sort of self-consciously fine art part, and it was very clear that that’s where I belonged. There was never a question in anyone’s mind that I would ever fit in any of the other categories.

CD: So it was intuition?

MG: Yes. The first time I was ever exposed to photography was through the Salt Institute for Documentary Studies in Maine, and that’s where I was introduced to the darkroom. That’s when I decided to take the classes at RISD, so this is backing up a couple of years, but even then I was on the writing side of this creative nonfiction documentary and how you build a documentary project. Even then, I chafed seriously at the rules of documentary practice and it was clear that I was not cut out to be a documentarian. I really appreciate the rigor with which I learned how to engage with studio lighting and studio cameras and work with models and I learned a lot technically. I was sent out on lots of photojournalism assignments that I detested and found incredibly difficult and then I found myself, 20 years later, writing a lot about why I hated that so much. I learned a lot, and I learned what I didn’t like, and it was quite clear where I belonged.

CD: So you’ve always been a rule-breaker?

MG: Always been a rule-breaker. Ask my mother.

CD: Well she’s next to be interviewed. So you mention the darkroom and I know you’re a darkroom nerd, what about your first experience with the darkroom just lured you in?

MG: I mean, in that case, my first exposure was for a documentary project at Salt, I was the writer and I was paired with a photographer who was slightly difficult. He would occasionally burn negatives when he didn’t like critiques. It wasn’t a very happy working partnership. So I started taking my own camera which was an inherited, beautiful Nikkormat camera that I loved and even though I’d never considered photography a real thing that I was doing, I would somehow often have a camera with me. I think the first time I understood how fun it was, I was up interviewing this woman for our project on Y2K prepping in Maine, so it was about two preppers. This was 1999. And again, with me not fitting into the documentary world, nobody at Salt wanted me to do this project because it didn’t fit their idea of the craft. Most of the projects were

nostalgia-based, like traditional lobster fishermen, but this documentary was too zeitgeist-y, I don’t know. I was discouraged from doing the project but I did it anyway. I started taking my own camera and making my own images. And then a friend of mine in the program showed me her darkroom, and my mind was blown. It was just this instant magic. I will say though, that I don’t love the darkroom.

CD: Oh?

MG: I have a weird energy in the darkroom. We have a love-hate relationship.

CD: That seems fair. A lot of things can happen in the darkroom.

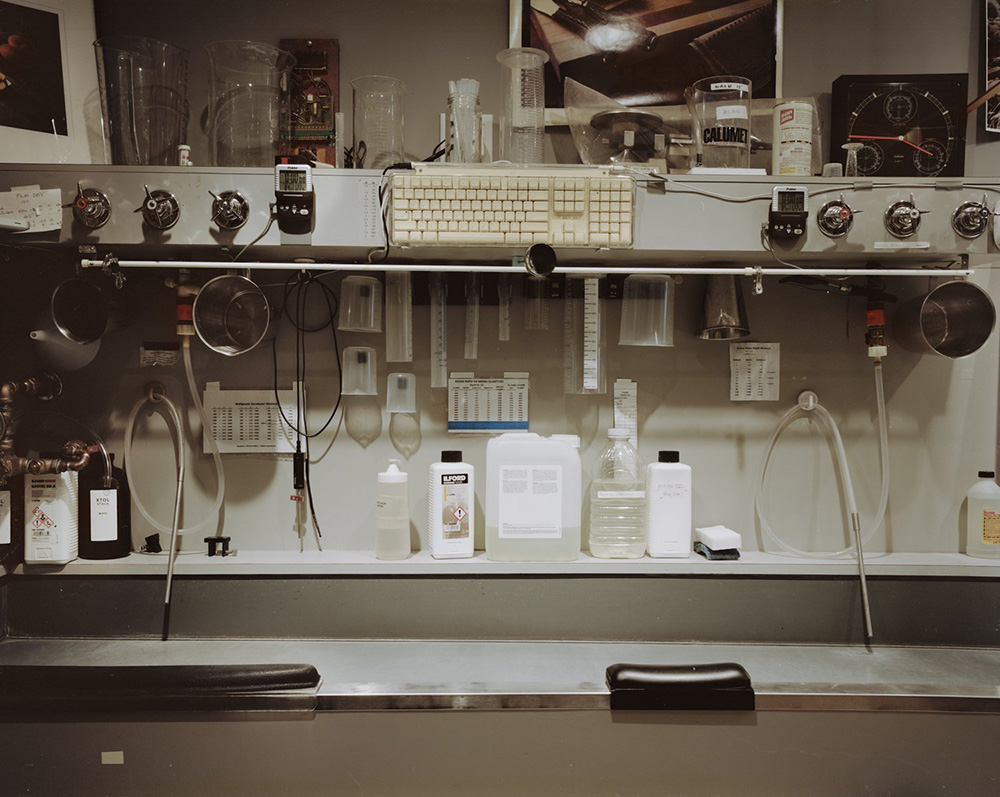

MG: I don’t romanticize the darkroom. I have a fair bit of negativity towards it. At the same time that I’m making a miniature version of one and photographing them like crazy, there’s so much to love about it but it’s loaded.

CD: There’s a lot of ritualism that happens in the darkroom. Do you have any rituals?

MG: I feel like I do. Am I self-aware enough to recognize them? I don’t think so. I’m very impatient in the darkroom, I feel like I’m my most impatient self. Which is funny, because it requires patience and I’m usually a patient person. It brings out my impatient streak that is probably not good for the longevity of the things I’m making. I’ll have to think about whether or not I have my own little rituals. I have trouble answering that because I haven’t had a rigorous or repeatable darkroom process in a long time. I process my color film in there, but I haven’t built up a practice because I’ve changed darkrooms so many times that I don’t have a particular relationship with this one besides processing film. I have worked in so many darkrooms over the years, I think too many. I’ve never made my own in a way that felt really perfect, always kind of a

scrappy relationship.

CD: Shared darkrooms are so different from private ones.

MG: Yeah, I’ve had too many personal darkrooms also, but we’re talking about in a closet. My first darkroom was in a closet on the third floor of a rented apartment and I had to duct tape myself in and out of it. I had to kneel in front of the enlarger because it was a sloped ceiling, with trays behind me on the floor, and I had to carry water with me in a bucket from the bathroom across the whole apartment.

CD: I feel like that’s sort of the trajectory of a lot of analogue photographers, we all make these sort of jerry-rigged darkrooms with no plumbing in a random awkward space where you can barely turn around and it’s always super sweaty.

MG: Yeah, and now I go around and photograph them where these astonishing human beings have engineered themselves the most beautiful custom-made sinks and print washers and plumbing with beautiful temperature controls, and they’ve just executed these gorgeous spaces that have me drooling.

CD: I know, I was looking through your Darkrooms project again and I just loved the shelving and organization or lack thereof that these darkrooms have. Do you know the people whose darkrooms you’re photographing? How do you find them?

MG: It’s all word of mouth usually, because darkrooms are such private spaces. I’ll hear someone has a darkroom, I’ll reach out to them and when I show up I ask them if they know anyone else who has one. So it’s been a sprawling word of mouth network.

CD: Are you going to continue doing this project? Do you like it?

MG: I’m having a great time. I haven’t made a lot of photographs in the world in a number of years. I go through these phases of not making photographs out and about and being very studio-centric. It has felt really nice to be taking photos and schlepping my camera around and setting it up and engaging in conversations with humans. I’m often more introspective in my practice and I don’t always need other people around, so it has been a surprising pleasure to interact with these delightful darkroom geeks. I’m trying to make this project more ambitious and look nationally and internationally.

CD: Have most of them been local?

MG: Most have been in New Mexico, I’ve photographed a few in Massachusetts. I also feel like I’ve been looking at New Mexico intensively as sort of proof of concept. It’s taken a little bit of getting used to photographing 4×5 color in these dark, cramped spaces.

CD: I was looking through a lot of your older projects and the way you approach them is funny, you’re a very funny person. When you’re making them are you having fun?

MG: Always.

CD: It seems like it. Even with the Inkset series you were doing with all of those different objects, was it a “What’s next?” kind of thing?

MG: Totally, I mean there are always loose parameters. In that project it felt important that the stuff be domestic. There was an underlying rule that I made for myself by focusing on domesticity. It was covid, I was locked at home with my kids, and so part of it was “What do I have lying around?” The domestic layer was important to me while finding humor. Rules meeting humor ends up generating a lot of work for me, and the humor often feels accidental. I don’t usually set out to be funny but I can’t avoid it. What’s the point if you’re not having fun? I guess funny and fun don’t have to go hand in hand but they tend to for me.

CD: Does fun translate to your book work?

MG: Books are a little bit more painful because for me they’re more vulnerable. I haven’t always felt like I know what I’m doing. So there’s an element of feeling outside of my customary skill set, which is a good thing, not a bad thing, but it is a place of vulnerability that does feel less fun. For a while it was re-embracing writing in my practice, which again I thought I was going to take writing sort of seriously as a big future thing when I was 21 or 22 and went to school explicitly to study writing. But then when I discovered photography I just tore that stuff up. It wasn’t a deliberate decision. I just turned my back on it and forgot that I ever truly did it.

CD: So it was a full abandonment of it?

MG: 100%.

CD: When did you feel it was time to revisit writing?

MG: I wrote a talk about how text showed up in a lot of my work. I am the biggest advocate for talk-writing as generative. I think actually talk writing was my writing. Writing lectures was the way that I was writing without acknowledging it. I love writing talks, I love giving talks, and I’m not a very performative person and performance has nothing to do with most of what I do. Except for my love of giving a good lecture in which I very carefully script. I’ve always felt very strongly about scripting lectures because I don’t trust myself entirely to speak off the cuff. I like humor and I like to really control the moment. Okay, it might also be because I’m a control freak, but I really like to give a good lecture. So for years I was channeling my writing energy into those and finding them very generative in terms of shaping the umbrella understanding of what I’m doing and shaping any sort of conversation about my practice. I wrote a talk about how text was showing up in sneaky ways in everything I was doing. Then I think that sort of started to spark things, I was writing an artist statement about a body of work and I just kept writing. And I was just like, “Oh, I have a lot of writing to do. Oh right, I like writing. Oh wait, I studied writing!”

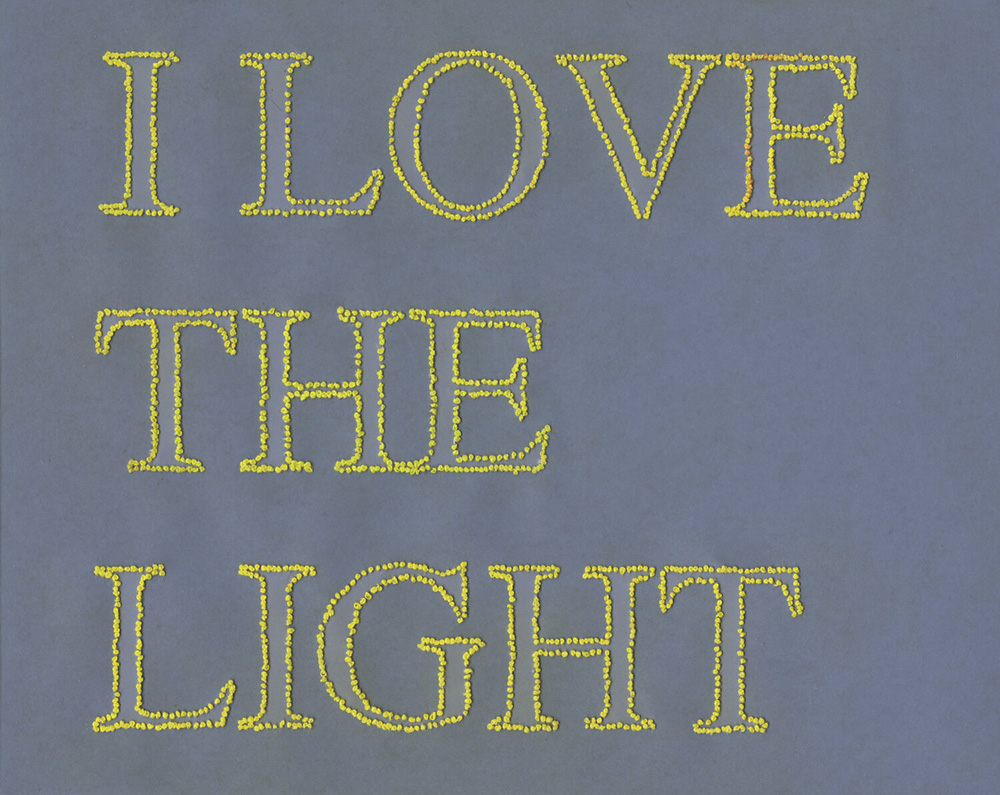

© Meggan Gould, Flickr Commentary, Epson Ultrachrome pigment ink on embroidery thread, stitched onto lumen prints on black and white photographic paper, 2018 – ongoing

CD: So do you think that your visual work feels less vulnerable?

MG: Yeah. I’ve been teaching and making photographs for so long that I can feel fairly confident in technical abilities, my skill set, and in understanding the dialogue I’m entering in. But writing, I feel rusty. I feel like I’m not entirely fitting into a genre that has a clear path. So I feel like I’m playing with the writing and playing with how the writing intersects with the images in a way that just feels new to me. And thus, scary.

CD: There’s also fun in that.

MG: Slightly more painful, but still fun. I’m having a great time doing it. Whether or not it’s capital-G Good is another question.

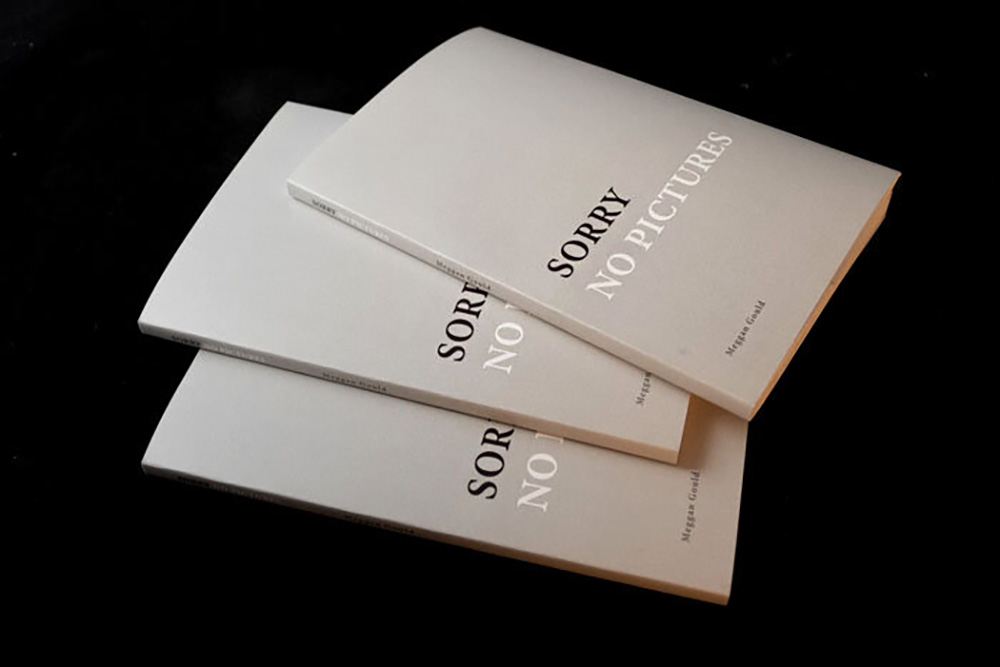

CD: In your book, Sorry, No Pictures, you’re sort of looking back, right? What was it like to revisit some of these projects? Do you still find them valuable in regard to what you’re currently working on? I know you have the tendency sometimes to cringe at some of your old work.

MG: Often cringe, yes. But cringiness and value are not mutually exclusive. I cringe at a lot of the things that I have made or things that I wouldn’t keep making, I guess. I see their value and I can still secretly like the fact that they exist and that I did them. I’m happy I made them and they feel foundational and that’s really important.

CD: I remember I had pulled one of your pieces from the Verso series that is in the University of New Mexico Art Museum collection and I sent you a picture of it, and you said it made you cringe a little. Do you still feel that way about it? Or is it just that specific piece? Or that anyone at any time can pull it and look at it, and the vulnerability that comes with that?

MG: A little bit. I have strange feelings about getting my work into the world, maybe. I guess that body of work for me now feels like an easy target, but it didn’t at the time. I’m not making that work anymore. It felt really important that I did. It hits any number ofcheck boxes for work that is about things that I’m interested in. In this case vernacular photography, breaking rules, text and image, and then mutual interactions and defining each other. So yeah, it feels like important work, but it also feels to me now…I don’t know. Not complicated enough.

CD: I just wondered because that’s two decades of work. What was that reflective process like?

MG: Aurora Photo Center did an exhibition version of the book last year, and it felt amazing to see that range of work on the walls. An acquaintance of mine came into the room, and I’m not sure if this was a compliment or insult, but they said it looked like a group show.

CD: Because everything felt so different?

MG: Because there were so many very different things that I have done represented on the walls, and I’ve been sitting with that ever since. I’m going to take it as a compliment because I don’t have a defining style, which I think is a good thing. I have tried every kind of process I can get my hands on because I think it’s fun and I think we should experiment with photography very liberally as a medium. I think people use it in way too constrained a way. I think that we should be thinking very extensively about what photography can and should do. I’ve looked at a lot of things, and I know the themes

that connect the work, and they aren’t necessarily visual, which I love. It was such joy for me to see this really old work, especially things I’d never ever shown before.

CD: And you also did a workshop that was paired with the exhibition?

MG: I did an anthotype workshop while I was there. I did another workshop in Taos a couple weeks ago.

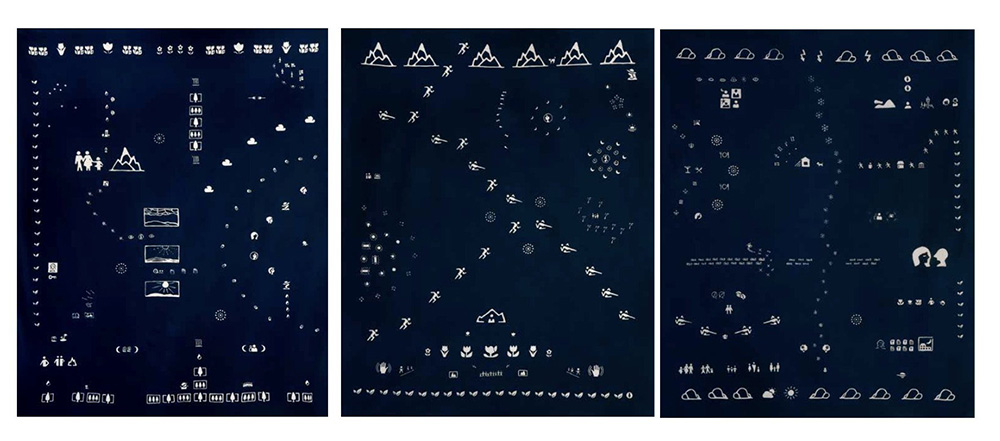

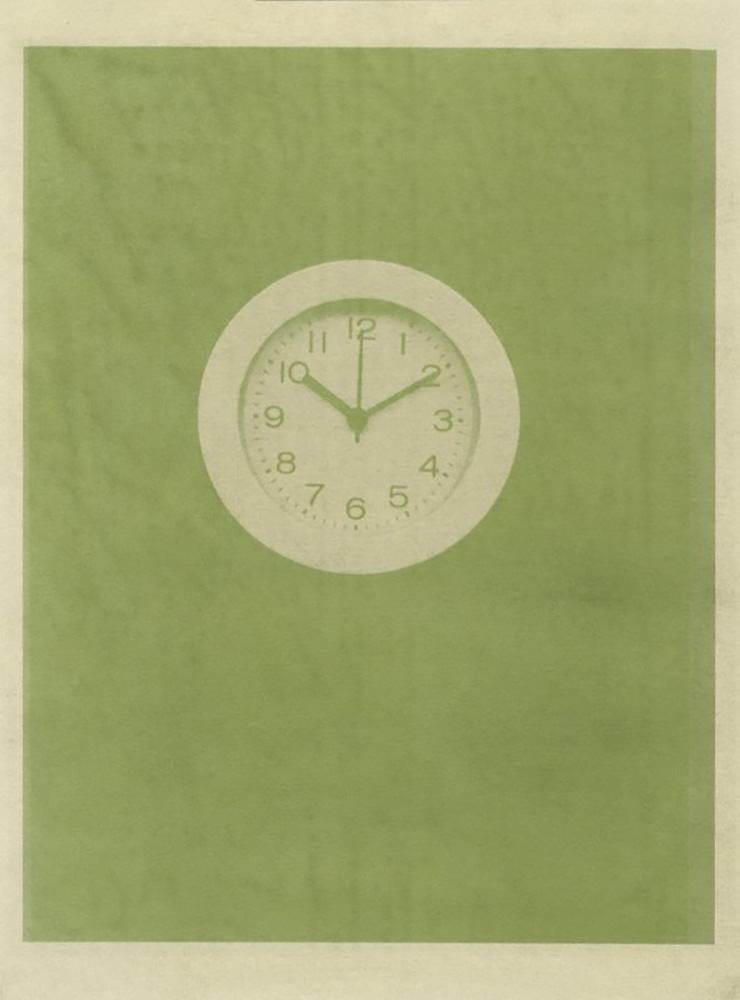

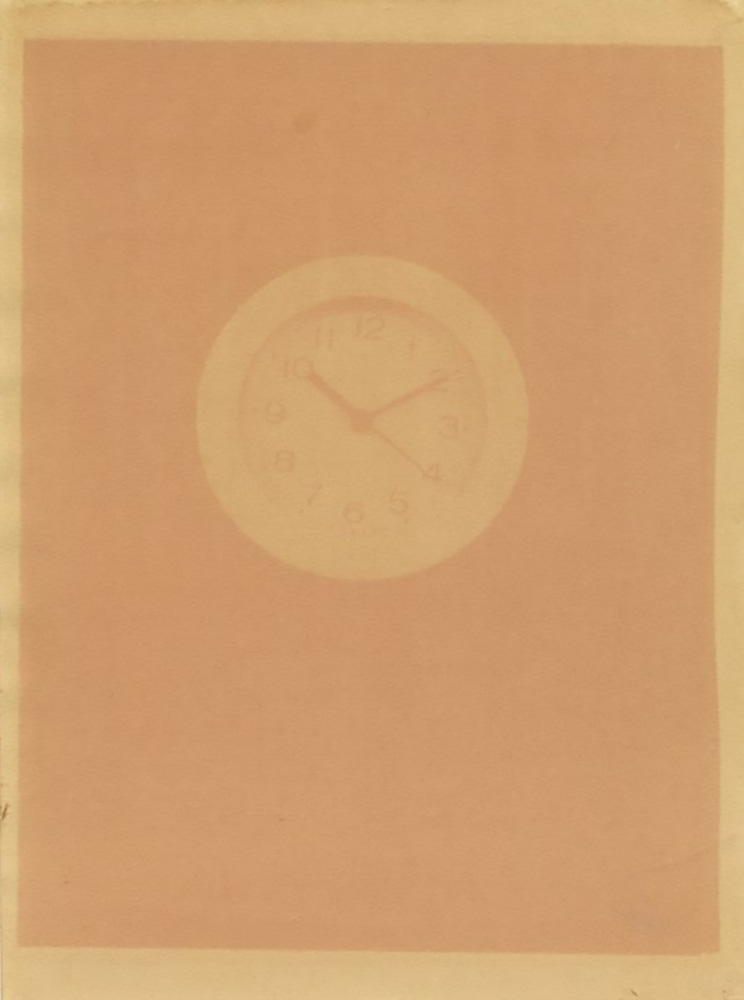

CD: And for the anthotypes you made for Happy Time Doomsday Time you used a lot of different materials right?

MG: For Happy Time Doomsday Time I used beets, onions, and spinach. Vast, broad experimentation of what would work, what I could make work.

CD: Those were successful anthotypes. They’re kind of a pain in the butt.

MG: Huge pain. I’m happy to step away from them for a while. I just did a show in Ohio in May where I made 90 of them. They’re tedious. I’m a patient person, again, just not in the darkroom.

CD: So back to Sorry, No Pictures, I guess I was just wondering how it felt to go down memory lane.

MG: Yeah, it was hard. I have never been an artist who makes work that is explicitly personal, I’ve made a lot of work about picking apart photography. I’ve made a lot of work that holds emotional life at an arm’s length, shall we say. Then in this book, tell-all memoir – or tell-some memoir – I reveal some secrets and talk about my past in a more open way than I have ever done.

CD: Was it cathartic?

MG: It was intense and terrifying to get it out into the world but it felt really good. I’ve found words to be much more specific, so they’re much more terrifying. It’s a good reminder for me that everything is personal. Even these anthotypes of clocks. The reason I have this patience to make them is partly because I am tethered to this very domestic reality right now, and it’s work that I can constantly be making in the background of my busy daily life with my kids. So it’s very personal and based in my reality where I need to make this work at this time. That book was a good reminder that everything is deeply personal even when we’re making very detached work about photography, we’re making it in certain ways because of life decisions that we make.I don’t think it’s talked about enough, how we show up in our work in ways that are not always diaristic.

CD: I would like to recognize that you are a powerhouse. You’re a working artist, a writer, you’re an incredible and encouraging educator, an invaluable resource to UNM, and you’re a mom. How do you do it? How do you find a balance with your teaching career, having an art practice, and everything else?

MG: Oh I don’t know! You just do what you have to do!

CD: Well you always seem so calm.

MG: Because I like all these things. I think that’s the secret. If you like doing it then you like doing it. I happen to very much like teaching photography. I happen to very much like my studio practice. I happen to very much like my family. So it all just works out. You show up and you’re doing something that’s joyful and sure there’s some baggage that comes with an academic job, which is sending a lot of emails and admin work and things that may not be the most pleasurable, but at the end of the day it’s still mostly really fun. I genuinely take pleasure in it and something I’ve acknowledged from the very beginning is that teaching is incredibly generative in my practice. I think my practice would stagnate if I wasn’t always on campus talking about photography. We’re all in the same dialogue together, the grad community is amazing, and I come out energized after a seminar. Every time I feel like I’m getting something selfishly, I’m totally getting material out of that. They mutually reinforce each other and I don’t feel like my studio practice would thrive in the same way if I wasn’t always talking about pictures. I’m harvesting the conversations we’re having and I spin it back into my studio practice. That is critical.

CD: That’s very poetic. So what’s next on the agenda?

MG: The physical exhibition of the California Museum of Photography (Shadow Archive runs from February 22, 2025 to July 27, 2025) collection is foreground in my brain right now, because I have what feels to me a really beautiful translation of the work, to take the negatives and honor them in a way that I did one way in the book and now I want to do it another way on the museum walls. That will happen within the next six months and I’m really excited about that project.

Chloe Dichter is a photographic artist currently based out of Albuquerque, New Mexico. Dichter’s practice centers around experimental approaches to image-making and the construction of sculptural photographs. Her work explores kitsch, humor, Jewish kinship, childhood cravings, and the preservation of objects. She received her BFA in photography from Western Washington University and is currently an MFA candidate and teaching assistant at the University of New Mexico. Dichter has shown work across the west coast and southwest including at Anderson Ranch Arts Center.

Instagram: @cyanodyke

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026

-

Time Travelers: Photographs from the Gayle Greenhill Collection at MOMADecember 28th, 2025

-

Suzette Dushi: Presences UnseenDecember 27th, 2025

-

Ragne Kristine Sigmond: Portraits of Painterly LightDecember 2nd, 2025