Jared Ragland: Art + History Competition First Place Winner

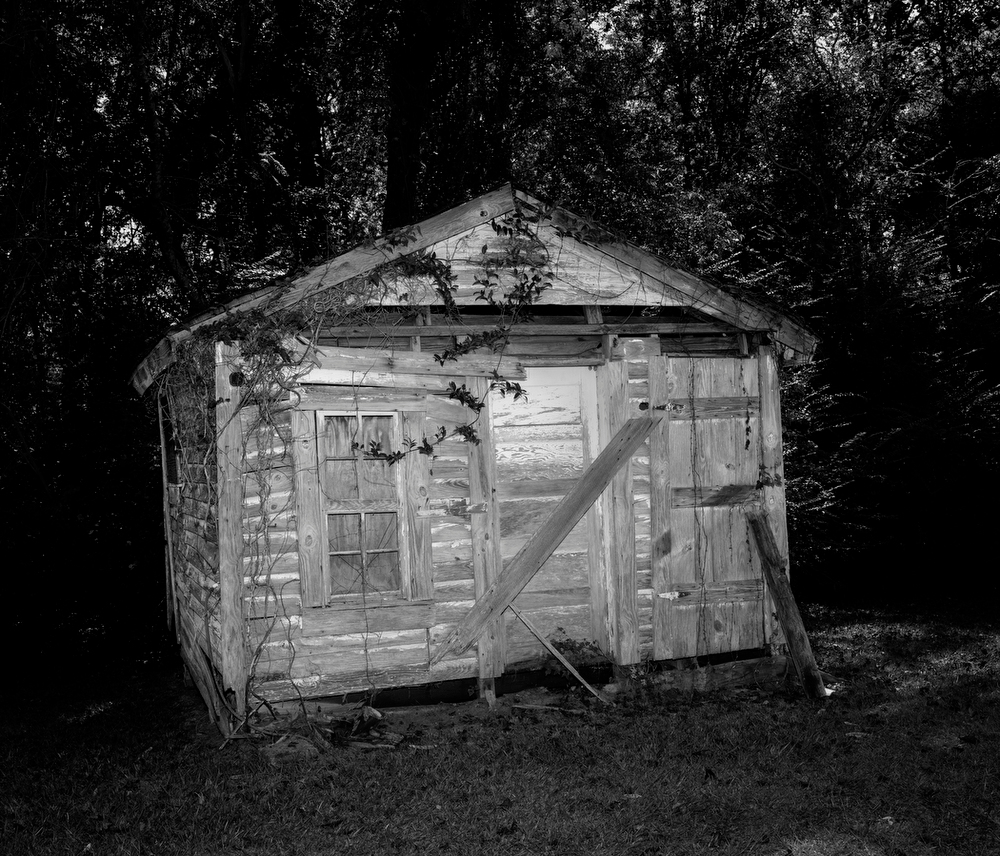

© Jared Ragland, “Spring Hill, Barbour County, Alabama—Michael Farmer,” 2020, from the ongoing series, “What Has Been Will Be Again.” Michael Farmer’s family has lived in Spring Hill for generations, where the predominantly Black community has faced a history of racial violence and voter disenfranchisement. On November 3, 1874, a White mob attacked the Spring Hill polling station, destroyed the ballot box, burned the ballots inside, and killed the election supervisor’s son. Many of the perpetrators of the massacre were known, but no one was ever convicted. Instead, Hilliard Miles, a Black man, was imprisoned after identifying members of the mob. Decades later, BB Comer, whom Mr. Miles had named as one of the perpetrators, was elected governor of Alabama. While 1,200 Black residents voted in the 1874 election, only 10 cast ballots in 1876. Almost 150 years later, little has changed. In 2016, Barbour County had the highest voter purge rate in the United States.

We would like to thank everyone who submitted to the inaugural Lenscratch Art + History Competition. We were impressed by the enormous number of compelling bodies of work, making it challenging to select just five outstanding projects. History and Art have been deeply intertwined for centuries. The winning projects we are featuring this week had a clear connection to history—exploring this relationship from personal, familial, and community viewpoints, extending to the history of places and countries, and even delving into mysteries and myths. Each image kept us wanting to discover more about the past, how it impacts the present, and—ultimately—the future.

Jeanine Michna-Bales and Sandy Sugawara

Fine art and documentary photographer Jared Ragland is an assistant professor of photography at Utah State University and a former White House photo editor. “What Has Been Will Be Again” explores how our past—our culture, traditions, ideals, and treatment of marginalized communities—can influence the present. His haunting photographs and meticulously researched captions pack a powerful punch, providing a deeper understanding of the tensions, anxieties and fears in many communities today.

© Jared Ragland, “Childersburg, Talladega County, Alabama—Sunshine turns soil in the Commons Community Workshop garden,” 2020, from the ongoing series, “What Has Been Will Be Again.” Sunshine turns soil in the Commons Community Workshop garden. As a response to national division and the COVID-19 outbreak, Sunshine and her husband Rusty bought a home in downtown Childersburg and created The Commons Community Workshop. Through their Fearless Communities Initiative, they maintain a community garden in a donated downtown lot, host trade days, and foster relationships with their neighbors as a means of “celebrating solidarity and strength.” The couple invited me to find them on Facebook where Sunshine posts Initiative announcements, vocalizes her opposition to vaccines, and shares her beliefs about global child sex trafficking networks, the threat of Marxism, and the coming of the end times.

What drew you to the topic of your Art + History body of work?

My home state of Alabama has known a deep and complex history. From Native American genocide to slavery and secession, and from the fight for civil rights to the championing of MAGA ideology, the national history written on, in, and by the people and landscapes of Alabama reveal problematic patterns at the nexus of larger American identity.

Working deep in territory considered a repository of national repressions, “What Has Been Will Be Again” has led me into each of Alabama’s 67 counties and across routes connected to brutal colonial legacies including the path of Hernando de Soto’s 1540 expedition, the Trail of Tears, and the Old Federal Road. Accompanied by historicizing captions, the photographs reflect upon the forced marginalization of African Americans, Indigenous people, and members of the LGBTQ+ population, and challenge the silence of historical narratives that have long failed to speak the names, dates, and places where such violence has occurred.

In the aftermath of the rise of MAGA ideology, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Black Lives Matter movement, I think each of us as artists have had to consider what our roles are as both artists and citizens and decide on what side of history we want to stand on. I also think it can be easy for artists to convince ourselves that certain stories aren’t ours to tell, or that we can’t make a significant impact—especially considering such big, deeply rooted, systemic issues or such overwhelmingly large problems. But “this is precisely the time when artists go to work,” Toni Morrison says, “there is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.”

© Jared Ragland, “Jacksonville, Calhoun County, Alabama—Taxidermy tableau with Confederate battle flag / along the de Soto route,” 2020, from the ongoing series, “What Has Been Will Be Again.” In 1540 Hernando de Soto entered present day Alabama with a company of 600 soldiers. In just a single year’s time, de Soto transformed life in Alabama and across the Southeast—waging war, enslaving Indigenous people, and introducing Western disease. It was de Soto’s expedition, and others like it, that caused a literal apocalypse. An estimated 55 million Indigenous people died between 1492 and 1600—a shift in population so large that it affected global temperatures.

What impact, if any, do you think this project has had or will have?

After casting my vote on Election Day 2020, I visited Spring Hill in Barbour County, Alabama, where on November 3, 1874, a White mob attacked the Spring Hill polling station, destroyed the ballot box, burned the ballots inside, and killed the election supervisor’s son. Many of the perpetrators of the massacre were known, but no one was ever convicted. Instead, Hilliard Miles, a Black man, was imprisoned after identifying members of the mob. Decades later, BB Comer, whom Mr. Miles had named as one of the perpetrators, was elected governor of Alabama. While 1,200 Black residents voted in the 1874 election, only 10 cast ballots in 1876. Almost 150 years later, little has changed. In 2016, Barbour County had the highest voter purge rate in the United States.

In Spring Hill I met Michael Farmer, whose family has lived in the community for generations. When asked what he hoped might come from the 2020 presidential election, Mr. Farmer said, “I hope the young folks might think about what their ancestors came through to get where we are.” Mr. Farmer recognized the importance of history and how it bears upon the present. Likewise, in her recent book, “South to America,” fellow Alabamian Imani Perry writes: “American exceptionalism, that sense that we are somehow special and ordained as such, is a myth sedimented on Southern prosperity…. But even if you are a lover of the national romance, integrity requires that the stories be at least halfway honest. It is not enough to set aside a little time or attention here or there to grieve our national sins, then, soft as butter, turn back to proclamations of greatness. Because history is an instruction. And what you neglect to attend to from the past, you will surely ignore in the present.”

Particularly at this current moment in American life, the act of remembering is political, and has great power. As “What Has Been Will Be Again” contends with personal and cultural memory making, it is my hope that it may contribute to the important cultural conversations happening across the country, particularly as those currently in power seek to foment political polarization, threaten democracy, further disenfranchise those already marginalized, and actively work to erase history.

© Jared Ragland, “Near Carbon Hill, Walker County, Alabama—Johnny Slingblade,” 2022, from the ongoing series, “What Has Been Will Be Again.” Carbon Hill has endured a troubled history of racism and violence. Originally established as a mining and railroad community by the Galloway Coal Company, Carbon Hill’s founders incorporated the town on Valentine’s Day, 1891 and nicknamed it “The Village of Love and Luck.” However, just two weeks prior a group of 200 White coal miners on strike from the Carbon Hill Coal and Coke Co. devolved into a violent mob upon hearing rumors their strike would lead to layoffs. Afraid their jobs would be given to Black workers, the mob terrorized the town. Between 2019-2020 Carbon Hill mayor Mark Chambers published several inflammatory statements on Facebook, including a call to “kill out” the LGBTQIA community, claiming immigrants were “ungrateful,” and aiming racist remarks at the Black Lives Matter movement. Walker County’s population is approximately 90% White and 25% live below the poverty line; more than 83% of residents voted for Donald Trump in the 2020 election, 85% in the 2024 election.

© Jared Ragland, “Russell County, Alabama—Controlled burn along the Old Federal Road,” 2022, from the ongoing series, “What Has Been Will Be Again.” First designated as a postal route by Thomas Jefferson in the early 1800s, the Federal Road stretched through Creek territory in lower Alabama and ushered in an era of national expansion, communication, and exploitation. Crudely constructed over ancient Indigenous trails, the road functioned as a major thoroughfare for the western migration of settlers and enslaved people into present-day Alabama for the first three decades of the 19th century. This colonial migration—what became known as “Alabama Fever”—ultimately led to the Creek Wars and the cessation of more than 21 million acres of Muscogee (Creek) territory. Following Indian removal, the plantation system quickly transformed the economy and produced unprecedented wealth while as many as 435,000 enslaved people labored in Alabama by the 1860’s. A majority of counties located along the Old Federal Road are today the poorest and most disenfranchised areas in the state, and where logging, milling, and chemical industries pose significant threats to the environment and local residents.

© Jared Ragland, “Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County, Alabama—Glitter scattered on ruins of the former state capitol building,” 2020, from the ongoing series, “What Has Been Will Be Again.” Yoholo-Micco, chieftain of the Upper Creek town of Eufaula, is said to have addressed the Alabama Legislature in 1836 at the state capital in Tuscaloosa before departing the ancestral Muscogee homelands on the Trail of Tears. Yoholo-Micco’s actual words are unknown, but White, colonial writers of history have portrayed the Creek leader as one who accepted Indigenous removal with an air of romantic resignation, going so far as to contrive his final words in a way to whitewash the genocide that had taken place over 300+ years’ time. Yoholo-Micco’s apocryphal address—which has been reproduced in Alabama history books and grade school curriculum for decades—reads, in part: “I come here, brothers, to see the great house of Alabama and the men who make laws and say farewell in brotherly kindness before I go to the far west, where my people are now going. In time gone by I have thought that the White men wanted to bring burden and ache of heart among my people in driving them from their homes and yoking them with laws they do not understand. But I have now become satisfied that they are not unfriendly toward us, but that they wish us well.”

Artist Statement

Alabama has known a deep and complex history. From Indigenous genocide to slavery and secession, and from the fight for civil rights to the championing of MAGA ideology, the national history written on, in, and by the people and landscapes of Alabama reveal problematic patterns at the nexus of larger American identity.

Working deep in territory considered a repository of national repressions, “What Has Been Will Be Again” has led me into each of Alabama’s 67 counties to trace routes connected to brutal colonial legacies—including the path of Hernando de Soto’s 1540 expedition, the Trail of Tears, and the Old Federal Road.

Social isolation is both a phrase and experience that has defined the recent past, and “What Has Been Will Be Again” expressly evokes the alienation that has characterized the moment. Yet the work considers sites for which isolation is nothing new—places where extracted labor and environmental exploitation have exacted heavy tolls for generations.

By combining a Southern Gothic visual sensibility with narrative captions, the photographs strategically focus on the importance of place, the passage of time, and the visual-political dimensions of remembrance to confront White supremacist myths of American exceptionalism and challenge the silence of historical narratives that have so long failed to speak the names, dates, and places where such violence and marginalization has occurred.

“What Has Been Will Be Again” is made with the generous support of The Do Good Fund, Magnum Foundation, Aftermath Project, Columbus State University, Alabama State Council on the Arts, Coleman Center for the Arts, and Wiregrass Museum of Art.

© Jared Ragland, “Marion, Perry County, Alabama—Birthplace of Coretta Scott King,” 2022, from the ongoing series, “What Has Been Will Be Again.” Coretta Scott and Martin Luther King, Jr. were married on June 18, 1963, at her family home in Marion. That evening, the couple was rejected by a Whites-only hotel in nearby Marion and were forced to spend their wedding night in a home that served as a Black-owned funeral parlor.

Jared Ragland (MFA, Tulane University) is a fine art and documentary photographer and former White House photo editor. He currently serves as Assistant Professor of Photography at Utah State University in Logan, Utah. His collaborative, socially conscious visual practice combines a range of photographic tactics with social science, historical, and literary research methodologies to critically confront issues of identity, marginalization, and the history of place.

Instagram: @jaredragland

© Jared Ragland, “Hayneville, Lowndes County, Alabama—site of Varner’s Cash Store, where Jonathan Myrick Daniels was shot to death by Tom Coleman,” 2020, from the ongoing series, “What Has Been Will Be Again.” Jonathan Myrick Daniels, a White Episcopal seminarian from Keene, NH, had come to Alabama following Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s call for clergy to join the march from Selma to Montgomery. Daniels remained in Alabama after the march, assisting with voter registration efforts, working at a health clinic, and helping integrate an Episcopal congregation. In August 1965 Daniels and fellow activists attempted to purchase drinks at a Hayneville store but were held at gunpoint by volunteer special deputy sheriff Tom Coleman, who demanded they leave the property. Coleman shot at 17-year old African American activist Ruby Sales, but Daniels pushed Sales to the ground and took the impact of the blast, dying instantly. Coleman was charged with manslaughter in Daniels’ death, but an all-White jury acquitted Coleman of all charges after deliberating for less than two hours.

© Jared Ragland, “Macon County, Alabama—Near the site of Fort Bainbridge / CDC Tuskegee Syphilis Study round-up sites,” 2022, from the ongoing series, “What Has Been Will Be Again.” Located near several important Muscogee (Creek) towns along the Old Federal Road, Fort Bainbridge was constructed in 1814 to guard the U.S. Army’s supply route into Creek territory. After the Indian Removal Act of 1830, local White landowners established a plantation system using extensive forced labor of enslaved people. Between 1932 and 1972, investigators from United States Public Health Service and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention enrolled a total of 600 African American men from Macon County in “The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male.” Participants were not informed of the nature of the experiment and left untreated for 40 years. As a result, 28 patients died directly from syphilis, 100 died from complications related to syphilis, 40 of the patients’ wives were infected with syphilis, and 19 children were born with congenital syphilis.

© Jared Ragland, “Birmingham, Jefferson County, Alabama—Jeremiah,” 2020, from the ongoing series, “What Has Been Will Be Again.” According to a 2020 investigation by Northeastern University, 123 Black people were killed by White police officers in Jefferson County between 1932–1968. In only two cases were officers charged for the killings. For 26 of the 36 years chronicled, the commissioner of public safety in Birmingham was Eugene “Bull” Connor, who infamously turned fire hoses and attack dogs on Civil Rights protesters in Birmingham in 1963.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Riley Goodman: Art + History Competition Honorable Mention WinnerApril 4th, 2025

-

Rachel Nixon: Art + History Competition Honorable MentionApril 3rd, 2025

-

Oleksandr Rupeta: Art + History Competition Second Place WinnerApril 1st, 2025

-

Jared Ragland: Art + History Competition First Place WinnerMarch 31st, 2025