Arin Yoon: Motherhood and the Military

©Arin Yoon, My son, Teo Principe, climbs in a 1117 Armored Security Vehicle during a family day visit to Fort Stewart, Georgia on November 15, 2016.

When asked to curate a week of posts leading up to Mother’s Day, I wanted to show artists whose work had not been shown before on Lenscratch. Because of my own endeavors and interest in family photographs, I chose artists whose work evolved from being a mother or a daughter.

I’m not sure how I discovered Arin Yoon, but it was probably on Instagram. I started following her because she lives in Kansas, near me. I remember seeing her photographs of her children that she posted from her Tallgrass Artist Residency, and thinking, “I want to meet her.” Lenscratch gave me the excuse to get in touch and go for a walk-and-talk with Arin.

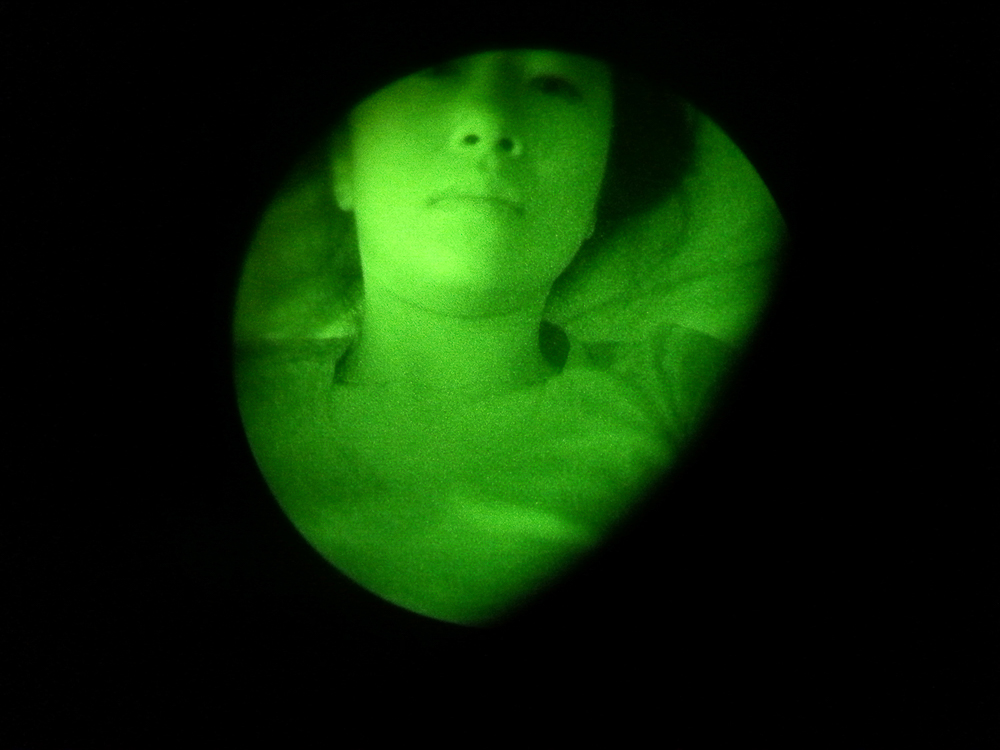

©Arin Yoon, Self-portrait through John Principe’s night vision goggles in San Bernardino, California on October 4, 2012. With this device of war, I began to explore my domestic space and my role in this military structure.

Motherhood and the Military

Ten years ago, I married a service member. I arrived at Fort Irwin, California, a remote Army base in the high desert, without knowing much about military life. Fort Irwin is the National Training Center for US Army troops right before they deploy and at that time, it was the height of the war in Afghanistan. While riding my bike on a desert road, a military convoy would pass me. Grandparents at a playground baby signed “helicopter” to a toddler when a chinook flew overhead. One day at Starbucks, there was a mix of soldiers in uniform and actors playing Afghan villagers ordering lattes and iced coffees. It was surreal stepping into this world. I looked up imagery about military families. I realized the visual representation of the military family experience is often reduced to a single image of the service member’s return home. An embrace. A tearful reunion. These images, however, do not capture the long preparation for deployments, training exercises that can be fatal, and spouses (95% women) who raise children alone. I started making pictures to better understand my role within this military structure, to learn more about this community and to document what this life looks like from someone living it. At one point, I realized I was no longer an outsider. There is a strong sense of purpose that binds this community together. When my children hear the sounds of retreat at 5pm each day, they stop playing, face in the direction of the flag that is being lowered, which is not visible to them, and they hold still. And they know the difference between a black hawk and a chinook, just like that toddler in the playground. –Arin Yoon

©Arin Yoon, Jiyeong Laue cares for her daughter, Serenity, behind their home in 2014 in Fort Irwin, California

Arin Yoon (she/her) is a Korean American documentary photographer, storyteller and visual artist based in Kansas. Her work focuses on the military community and the impacts of war, trauma and healing, notions of family, women and issues of identity and representation. Arin is a National Geographic Explorer, a We, Women Photo artist, and an International Women’s Media Foundation fellow. She is a member of Women Photograph, Diversify Photo and the Asian American Journalists Association. She is an alumna of the Eddie Adams Workshop and the Missouri Photo Workshop and was a participant of the 2023 New York Portfolio Review.

Her work has been featured in National Geographic, The New York Times, The Washington Post, TIME, NPR, and ProPublica, among other publications. Arin has exhibited at venues such as the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History in Seoul, Daegu Arts Center, Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and Photoville and A.I.R. Gallery in New York. She has an MFA in Photography, Video and Related Media from the School of Visual Arts and a BA in Political Science and a BA in English Language and Literature from the University of Chicago.

Follow Arin Yoon on Instagram: @arinyoon

©Arin Yoon, I pose for a self-portrait at a B&B in between duty stations in Leavenworth, Kansas on July, 9, 2014.

DD: I know from my experience that editing such personal family photographs can be a challenge. So I’m curious about how you choose which images to show as your artwork?

AY: Since I have been working on my project, To Be At War, for over ten years, it has evolved as I evolve. When I started, I didn’t know it was going to be a project. I just started taking pictures of the military community in order to understand my new life as a military spouse. I started by asking people I met if I could document their everyday lives and then I began getting hired to take photos of community functions like holiday events, communions, mother-daughter dances, etc. Photography gives you a license to enter worlds you may not have known about or been asked to enter. At first, I shot medium format film. But after having kids, I couldn’t carry all my camera equipment and my baby gear and the babies so I had to forgo my cameras. But if a moment arose, I would use my phone to capture certain moments. It was during this time in my life when I had this recurring dream that there was a scene or situation that was just perfect and I reached for my camera and realized I didn’t have it or that it was broken. I was definitely having anxiety about not being able to make pictures consistently. So to answer your question, sometimes I don’t develop my film for months and then finally take a look and think about if a picture might fit into the project. Or there’s an image that I envision in my head and then it somehow comes together slowly. Like I knew I wanted to photograph John’s hearing aid but the couple of times I tried photographed it, it just wasn’t working. But one day when my son’s face was close to John’s ear, I knew that was the picture I was trying to make. Sometimes I envision what kind of image I want to make, other times there are events I want to cover to illustrate this life. And so the editing is inconsistent and there are different types of images, and sometimes I’ll go back and look at my images from years ago again and find something I overlooked. Or the opposite, I take out what I thought was an important image. The project is alive in that way – it changes as I change and as the world changes. And of course, feedback from peers and mentors is always critical in developing any project, especially long form documentary projects and I constantly seek out advice on sequencing and selecting images. It’s important to have outside eyes on a project that is so personal.

DD: Has your photography project changed your relationship with your children in any way?

AY: Last Mother’s Day, my son’s first grade teacher had the kids finish the sentence, “My mom is really good at ________.” and draw a picture. And he wrote “takekig qichris” (which is clearly “taking pictures”) and the drawing is of me with my camera on a tripod taking a picture of him and his sister with their arms around each other. And more recently my daughter drew a picture of us watching a sunset and wrote, “ Me and my mom and bruthr wacht the sunset. It wus pritey. Me and my mom touc pictures of the sunset.” And in the picture, we are all smiling. So I think for them, this is an activity that they know we do together and it can be fun and creative but I am always mindful of how they are feeling and if they want to participate and how they want to represent themselves. They notice changes in light and when there’s interesting patterns of light, they point it out to me. “Mom, look at this shadow on my foot! Take a picture!” And for me, that is a gift – that they are learning to see in this way and it’s something that I have shown them by making pictures with them. And they teach me how to see too. They find joy and humor in so many everyday things which in turn opens up how I see the world. When you look through kid lenses, it really is more magical. I imagine as they get older, they will want to participate less and want more space, so I savor as much as I can now. Maybe in the future they will direct the photos when I’m an old lady telling me to climb a tree barefoot or lay down in a stream with my eyes closed. I will be happy if that happens.

©Arin Yoon, John holding Teo the night before saying goodbye for his first combat deployment as a father, Fort Stewart, GA 2015

©Arin Yoon, Denise and Andy Buissereth, before deployment in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas on April 15, 2015.

DD: What question are you most often asked about your work?

AY: People ask me how the military community, especially how my husband, John, feels about me documenting this life. John has been generous in his openness about his experiences. We worked together on a story about the 20th anniversary of the war in Afghanistan. It was a mix of his vernacular photos that he took during combat deployments to Afghanistan juxtaposed with my images of domestic home life. As we went over his images together for the captions, we talked about his experiences, which he doesn’t discuss too much. After the story was published, he said, “I feel like working on this with you brought us closer together.” I’ll always remember that. It affirmed to me the importance of doing this work on a personal level but also as a platform for others to express themselves. For the past couple of years, I have been working on doing more community engagement work and sharing first person narratives of their experiences as members of the military community – service members, spouses and military children. And some of these stories involve trauma, so they are not always easy to tell because every time a story is told, the trauma is revisited. So it is a slow and gentle process. My perspective is just one of many – just one truth – so I think the more stories that are shared, the more powerful the work becomes in reflecting this multifaceted collective experience.

©Arin Yoon, Homecoming. They arrive in the middle of the night. Eyes sleepy, searching for their families. They look like ghosts- in this space between deployment and home. Some of the soldiers are crying. Maybe it’s just mine. Fort Stewart, Georgia, October 23, 2018.

Deanna Dikeman has photographed her parents and relatives in Iowa and Nebraska for over 30 years. She was recently named a 2023 Guggenheim Fellow.

Instagram: @deannadikeman

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Paccarik Orue: El MuquiDecember 9th, 2025

-

Lauri Gaffin: Moving Still: A Cinematic Life Frame-by-FrameDecember 4th, 2025

-

Dani Tranchesi: Ordinary MiraclesNovember 30th, 2025

-

Art of Documentary Photography: Elliot RossOctober 30th, 2025

-

The Art of Documentary Photography: Carol GuzyOctober 29th, 2025