THE CENTER AWARDS: ENVIRONMENTAL AWARD: JOHN TROTTER

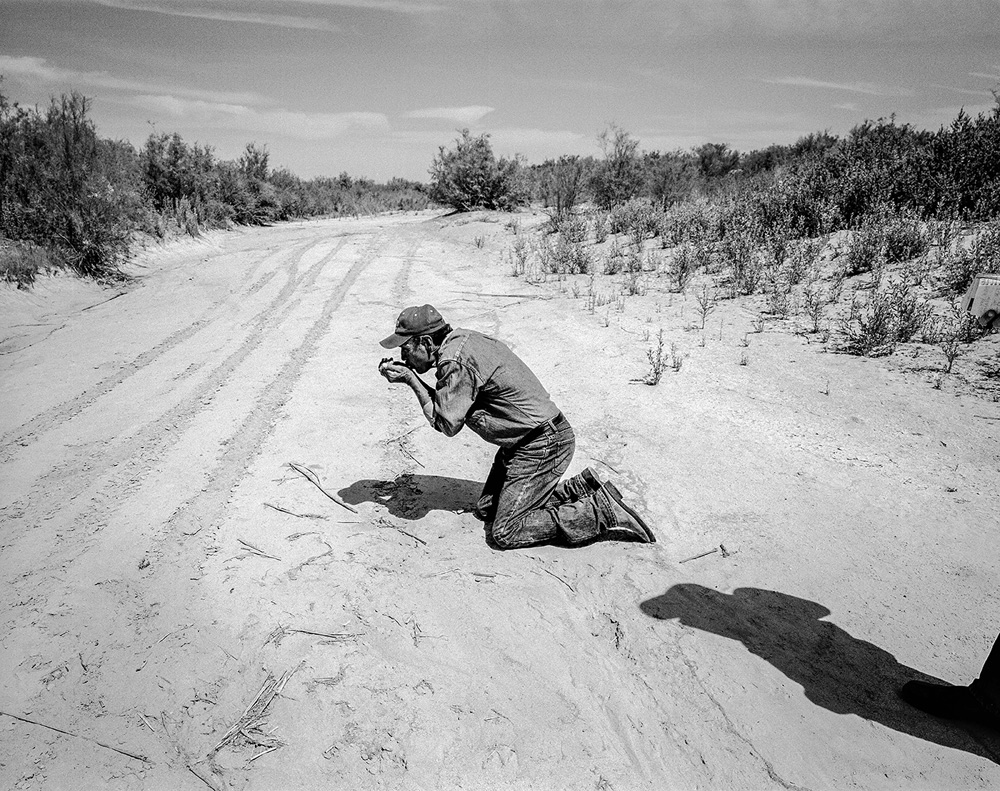

© John Trotter, Local environmentalist Juan Butrón pretends to drink water from the dry channel of the Colorado River as he goes looking for the leading edge of the slowly moving pulse flow of water from the Morelos Dam, a few kilometers upstream. Within a few hours, it would reach this spot, though in less than two months the riverbed would once again be dry.

The CENTER Awards recognize outstanding images, singular or part of a series, in three categories: Personal, Social, and Environmental. All submissions will become part of the CENTER archive serving as an ongoing mission-driven fine art and documentary imagery resource.

Congratulations to John Trotter for being selected for CENTER’s Environmental Award recognizing his project, No Agua, No Vida. The Environmental Awards recognize work focusing on the state of the ecological environment. Topics may include but are not limited to, conservation, biodiversity, ecology, climate change, or other issues concerning the natural world. All projects exploring ecological relationships, topics, or themes are eligible. The Award includes Professional Development Seminars, a Review Santa Fe Admission and Project Presentation, a Project Publication with Lenscratch, and inclusion in the CENTER Image Library & Archive.

JUROR: Sabine Meyer, Photography Director, National Audubon Society, shares her thoughts on the selection:

As a photo editor working in the non-profit environmental space, I am often asked to define how photography can not only expose but also help environmental issues.

Photography is at its most powerful when it frames – or “reframes” – human impact on our planet, its inhabitants, and its resources in such an effective way that, that very single photo frame, gets us, the viewers, to stand up, say “enough” and take action.

To achieve that goal, the spectrum of photographic tools is wide and varied, with diverse avenues of practice, from documentary photography to fine arts studio creations, to site specific projects, to multimedia and mixed media works.

All of this year’s entries span this expansive definition and made for a very worthy and robust collection of projects that, in turn, question the self, our natural resources, our relationship to our planet and its many living forms and so much more.

No Agua. No Vida: the Human Alteration of the Colorado River rose to the top for me because it lays bare that there is no denying we are experiencing a serious water crisis in the West.

20 years in the making, Trotter’s collection is a series of gorgeous photographs that harken back to the years of the Farm Security Administration’s photographic documentation of the Great Depression.

His black-and-white frames are composed with rigor and the minimal but decisive information that encapsulates critical concepts centering around water overuse and hence scarcity, around human alteration of natural water flows and hence downstream consequences on people’s lives and livelihoods, on natural habitats and wildlife.

Trotter is able to balance visual beauty with a stark and harrowing reality – his eye is poetic and unflinching but also compassionate to the people he photographs – he is showing us, not teaching us with his photos.

Let’s hope we learn and take at heart his plea: water is the source of life, and we need to take better care of it.

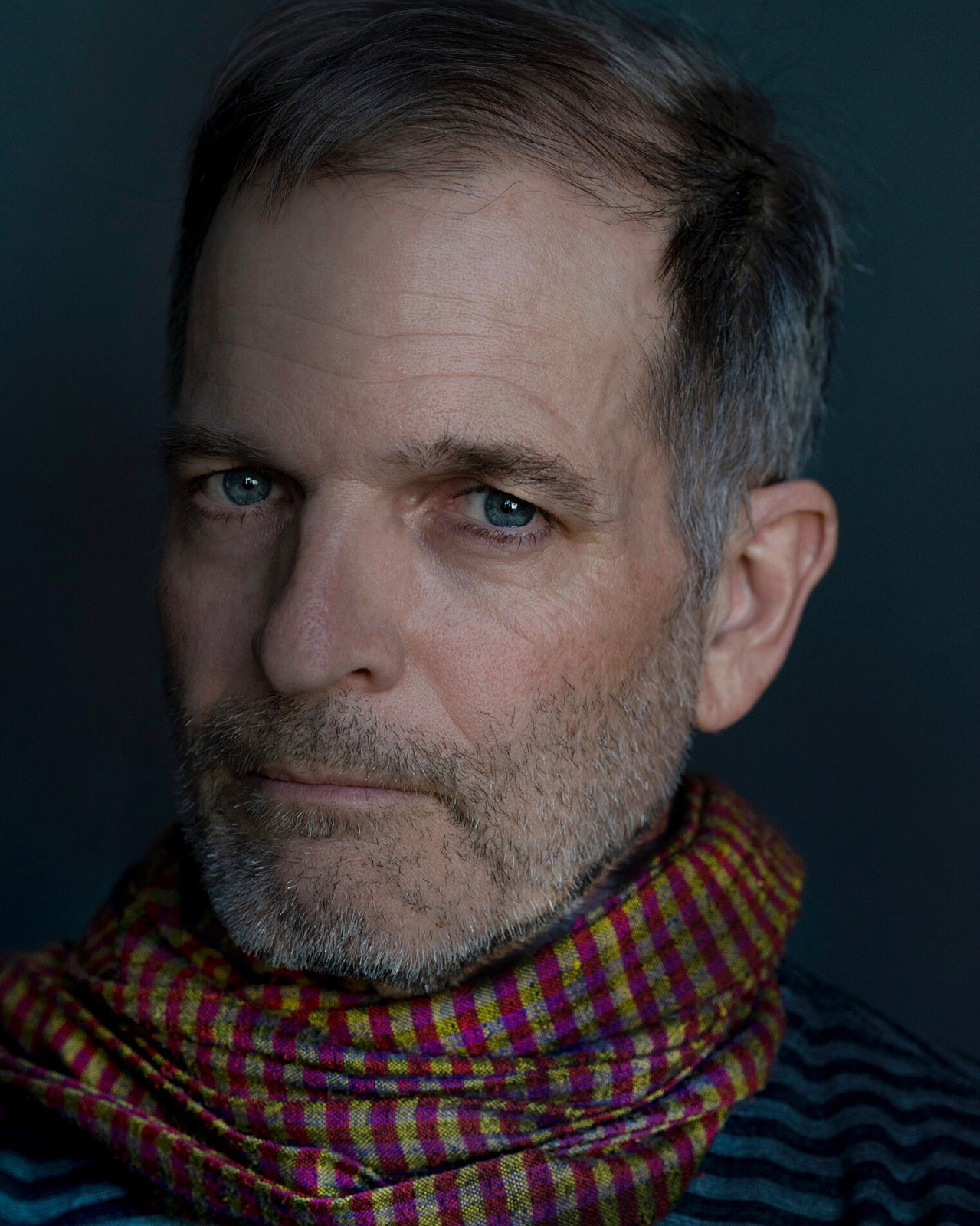

John Trotter, 63, worked as a newspaper photojournalist for 14 years, locally and internationally, until March 24, 1997, when he was nearly murdered by a half-dozen young men while on assignment for The Sacramento Bee, where he worked as a staff photographer. After many years in a box, photographs he took during his long recovery from his subsequent brain injury are becoming a book, The Burden of Memory.

In 2001, Trotter began photographing in Mexico for his project No Agua, No Vida about the human alteration of the Colorado River. He has photographed along the entire 2,250 km length of the river, from its headwaters in the Rocky Mountains to the desiccated remains of its delta above the Gulf of California. He has lived in New York City since 2000, and in 2017 became one of the founding members of the collective, MAPS Images.

Follow John Trotter on Instagram: @unamericain

© John Trotter, Lake Powell was born in September 1963, with the completion of Glen Canyon Dam, to fulfill the obligations of the Upper Basin States of the 1922 Colorado River Compact (Wyoming, Utah, New Mexico, and Colorado) to deliver an annual allotment of water to the Lower Basin states (Nevada, California, and Arizona) and Mexico.

No Agua, No Vida

Since 2001, I’ve been photographing the consequences of the sweeping human alteration of the Colorado River, in the Southwestern United States and Northwestern Mexico. The Colorado, I soon learned, was greatly reduced from what it once was and no longer makes its ancient rendezvous with the Sea of Cortez, between the Baja California peninsula and the Mexican mainland.

Forces north of the border had other destinations planned for the river’s water, and in 1922 divided its annual flow between seven U.S. states and Mexico. They built an extensive network of dams, stilling much of the once-roiling river and creating the foundation on which the Southwestern United States has been built.

But as it has turned out, the foundation of everything, the premise of 1922, was based more on wishful thinking than fact and up to 25% more water has been promised to the river’s users than actually exists.

I’ve taken many trips to the river, documenting its delivery infrastructure, and the cities and farms dependent on it. I am most struck by the profound disconnection that the river’s users have with this vast, glorified plumbing system, which provides them with water – one of the few things in the world without which we cannot survive. Despite years of warnings from scientists, the users have been drawing down the system’s two biggest reservoirs, Lake Powell and Lake Mead, faster than the climate change-depleted river can replenish them. In mid-2022, Lake Powell dropped to its lowest level since becoming operational in the mid-1960s and its continuing decline endangers the entire system below.

As the climate change emergency continues to shrink the Colorado, the only hope for mitigating the inevitable suffering for more than 40 million people directly dependent on the river’s water will be cooperation informed by a better understanding of the system’s totality. Though exploitation of the river has created animosity between its users since even before the 1922 Compact, the stakes have never been higher. – John Trotter

© John Trotter, Resting workers watch a Mexican military anti-narcotics plane from a former wetland in the Colorado River Delta, where the river no longer reaches the Sea of Cortez.

© John Trotter, The Central Arizona Project (CAP) Canal, at Bopp Road, outside Tucson, Arizona, which has brought Colorado River water from almost 500 km away.

© John Trotter, A young onion picker ties rubber bands around bunches of scallions in a Sonoran field on a late autumn afternoon in Mexico’s Colorado River Delta. His working day began in the darkness, at 5 AM.

© John Trotter, The Blue Angels, the United States Navy’s aerobatic flight group, performs a flyover of Hoover Dam as part of the celebration there of the centennial of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the federal entity that built the dam in the 1930’s.

© John Trotter, The Big Surf water park in Tempe, Arizona, with the oldest recreational wave machine in the United. States. The city receives Colorado River from the Lake Havasu, over 300 kilometers away, via the Central Arizona Project Canal.

© John Trotter, Lake Mead intake pipes, which provide Colorado River water for nearby Las Vegas, Nevada. The city’s water agency will be spending well over $1 billion to build a new intake and attached pumping station as insurance against the continuing decline in the level of Lake Mead. The new intake will be near the bottom of the lake and would still provide water to Las Vegas.

© John Trotter, Mexican biologist Alejandra Calvo holds a Wilson’s warbler caught in a research net erected in the Laguna Grande habitat restoration area in the Colorado River Delta. Even with 90% of its historic wetland gone, the delta remains an important stopover on the Pacific Flyway for migratory birds.

© John Trotter, Years of diligent inspections by National Park Service Glen Canyon National Recreation Area employees of boats entering Lake Powell failed to keep invasive quagga mussels out. The mussels, natives of Ukraine, can seriously disrupt the ecology of any body of water with their intensive filter feeding. Additionally, quagga mussels are prolific breeders.

© John Trotter, At Expedition Island, in Green River, Wyoming, where on-armed U.S. Civil War veteran and scientist Major John Wesley Powell and his party began both their 1869 and 1871 explorations of the Green and Colorado Rivers by wooden boat. Green River Butte is visible in the background.

© John Trotter, Fresh local oranges for sale in Phoenix, Arizona, mostly from groves irrigated with Colorado River water brought from Lake Havasu, over 300 km away.

© John Trotter, The sprawl of Phoenix, Arizona from South Mountain Park. The explosive growth of Phoenix began after the completion of the Central Arizona Project Canal began bringing Colorado River water from Lake Havasu, about 300 km away.

© John Trotter, Built on what was once the land of the Yavapai people, the town of Fountain Hills, built by Robert P. McCulloch (who moved the old London Bridge to Lake Havasu) has the world’s fourth tallest fountain. EPCOR, a private company, provides Colorado River water from the Central Arizona Project Canal to the community.

© John Trotter, A broken sprinkler on Pebble Road, near the intersection with Green Valley Parkway in Las Vegas, Nevada. With an average annual rainfall of only 10.4 cm, much landscaping can only survive with regular irrigation.

© John Trotter, Harvesting head lettuce outside of Yuma, Arizona, where agriculture, which grows winter vegetables from the entire country, is almost entirely dependent on the Colorado River for irrigation.

© Jonh Trotter, Setting up the sound system for an outdoor December wedding at the Papago Golf Course, in Phoenix, Arizona.

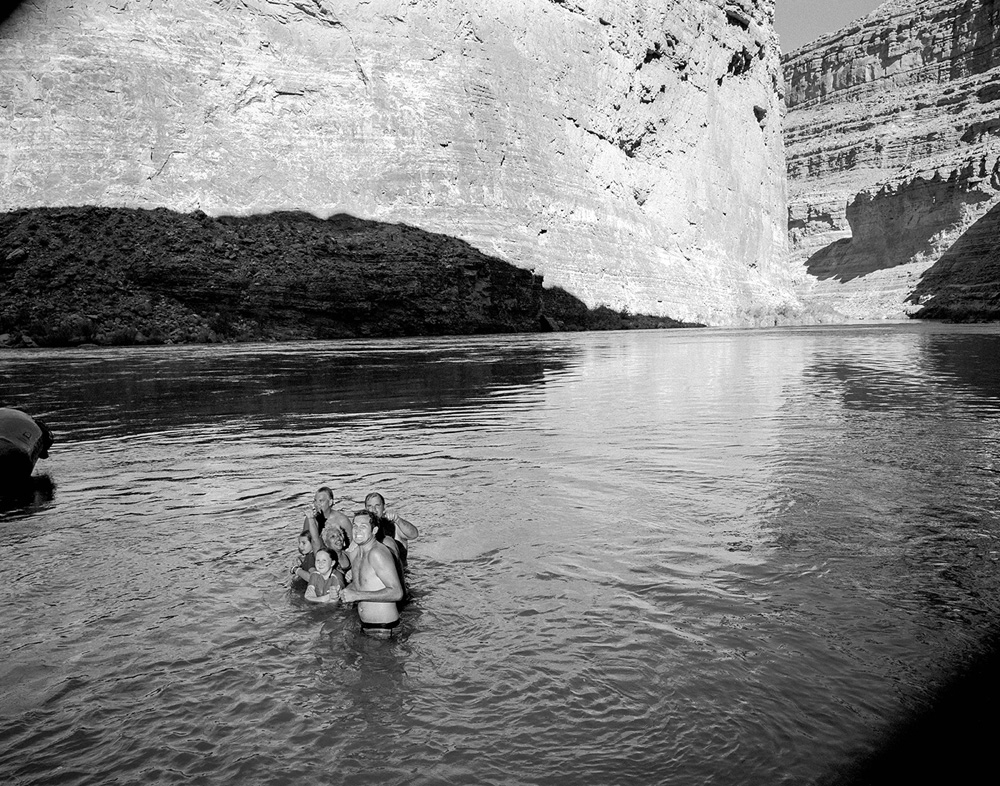

© John Trotter, People on a raft trip on the Colorado River through Grand Canyon National Park stop for a morning break at Red Wall Cavern.

© John Trotter, A pickup truck churns up the dust from millions of years of Colorado River silt, deposited in the Mexican Delta, before the giant dams were built that changed everything.

© John Trotter, A Cucapá youth fishes for crabs near the mouth of the Colorado River in the Mexican state of Baja California, waiting for his father to return in his boat from curvina fishing. Because of diversions upstream in the United States, the Colorado River itself no longer reaches the ocean and the water at the river channel’s mouth is a brackish mix of seawater and irrigation runoff.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Paccarik Orue: El MuquiDecember 9th, 2025

-

Lauri Gaffin: Moving Still: A Cinematic Life Frame-by-FrameDecember 4th, 2025

-

Dani Tranchesi: Ordinary MiraclesNovember 30th, 2025

-

Art of Documentary Photography: Elliot RossOctober 30th, 2025

-

The Art of Documentary Photography: Carol GuzyOctober 29th, 2025