The Female Gaze: Judith Nangala Crispin – A Committed Practice

©Judith Nangala Crispin, There’s a door inside a nebula— where the dead go through. Marvin and Dorothy, still spinning, find one another on the other side of stars (2025) from the series The Dingo’s Noctuary. (Lumachrome glass print, cliche-verse, chemigram. Cat-killed New York chipmunk and grey squirrel on fibre paper. Re-exposed with sane, ochre, wax, house paint, Vegemite and sand. First exposure 13 hours under perspex in New York. Second exposure, 36 hours in a Braidwood greenhouse)

Judith Nangala Crispin is an acclaimed poet, visual artist, motorcyclist, conservationist and volunteer firefighter, who lives on unceded Ngunnawal/Ngambri Country near Braidwood on the NSW Southern Tablelands. Her poetry has won the Blake Prize, been nominated for a Pushcart Prize, and been shortlisted for many awards including the Peter Porter Prize. Her visual art has won her residencies, awards, and wide acclaim, in Australia and overseas.

She spends part of each year living and working with the Warlpiri, her adopted people, in the Northern Tanami Desert. Her images and poems have been included in the Lunar Codex time-capsule which was deposited on the moon as part of the Blue Ghost mission in 2024. She is proud member of Oculi collective and FNAWN (First Nations Australia Writers Network), and an Artist in residence with Music Viva.

Judith is a descendant of Bpangerang people from the Murray River and acknowledges heritage from Scotland, Ireland, France, Armenia, Mali, Senegal and the Ivory Coast. She does not speak for any Aboriginal groups, tribes or clans and claim no cultural authority. Judith chooses not to access grants or funding intended exclusively for Aboriginal people because of her relative privilege and identity as a mixed heritage person.

Judith has directed and worked on two major social justice research projects–The Julfa Project, which preserved photographic records of a destroyed Armenian cemetery and digitally reconstructed the site from new and existing images; and Kurdiji 1.0, an Aboriginal suicide prevention app, which strengthens resilience in young indigenous people by reconnecting them with community and culture.

©Judith Nangala Crispin, Henry’s Country (2018) from the series, Tanami Desert (scanned 35mm negative)

©Judith Nangala Crispin, Myra and Biddy (2018) from the series Tanami Desert. (scanned 35mm negative)

Judith Nangala Crispin creates profound, haunting photographs that often appear not to be photographs at all. I’ve been following this work from a distance for several years, curious about how she created it and why. Her practice is not for the faint of heart, as she uses deceased animals and blood in making the work. I reached out to Crispin and asked her if she would allow me to interview her for The Female Gaze, and thankfully, she said yes.

Crispin’s story is one of, if not the, most interesting of the interviews I’ve conducted since I began writing The Female Gaze feature in late 2020. She responded quite candidly and thoughtfully to my questions, and her responses lay bare her touchstones to her mixed heritage.

Like many artists of Indigenous descent, Crispin’s focus on Native beliefs and practices creates poignancy born from the troubled and painful history of colonialism. My home, Hawai’i, is another land where Native people were disenfranchised from their culture and language and whose kingdom was overthrown. This is something I think about often, especially because I myself am an intruder on their land.

Crispin’s work, though very different in look and feel, reminds me of the work of Native Hawaiian photographer Kapulani Landgraf, due to the way they both use artifacts of culture in making work that speaks directly to their particular indigenous histories and both have elements of social justice underpinning the work.

I hope you enjoy this interview as much as I did.

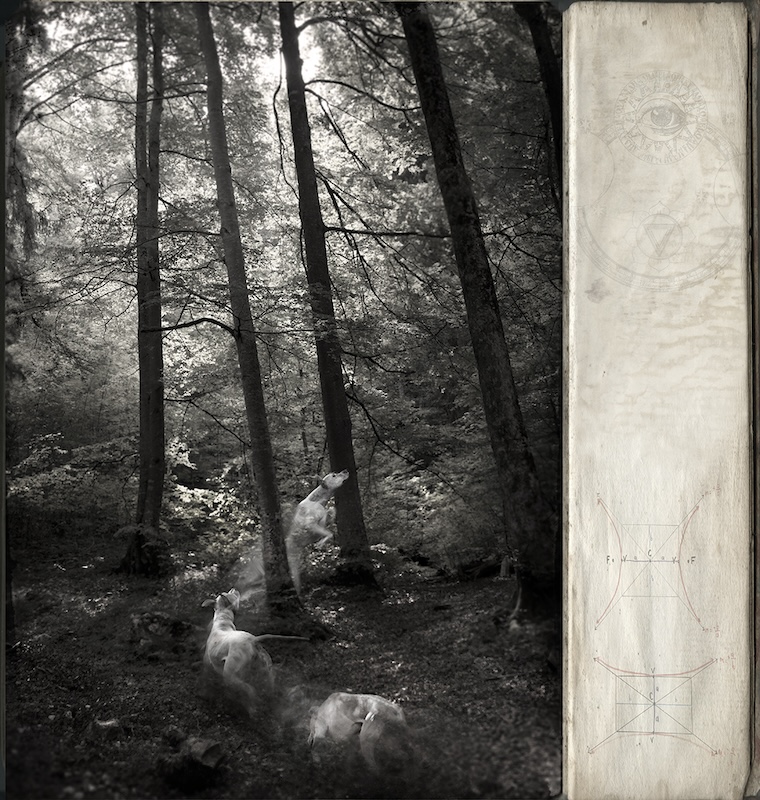

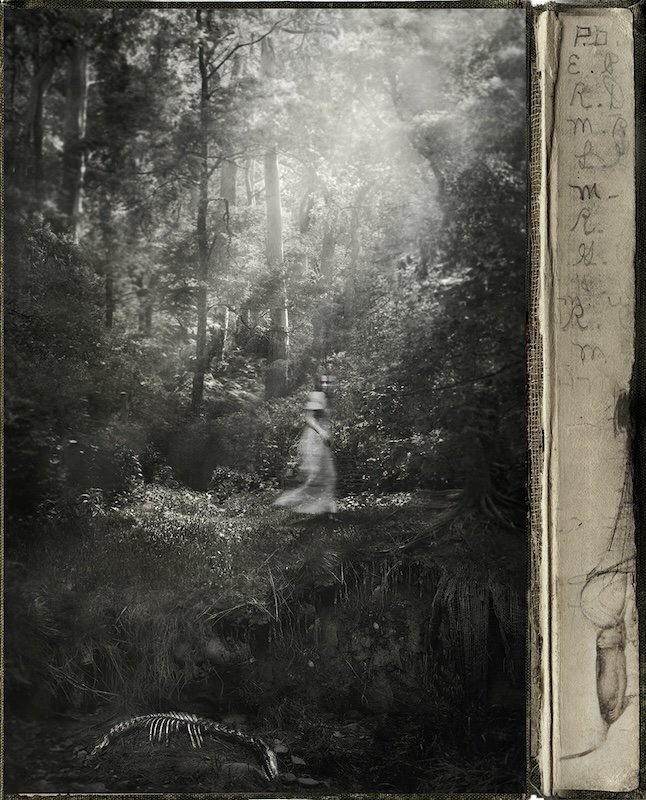

©Judith Nangala Crispin, Woods that no real dog would enter (2011) from the series Marchen. (scanned negatives & pages, graphite, indian ink and blood; pigment prints on Japanese Gampi paper.)

DNJ: Tell us about your childhood.

JNC:I spent the first half of my childhood in Sydney, and the second half in the bush.

My parents were impoverished; the kind of poverty many would struggle to comprehend. They’d lost one child, my sister, to illness, and they blamed themselves and their poverty for that loss. My father would work during the day, then study at night, becoming qualified as a lawyer through the old Barristers’ Admission Board, as university study was out of reach. One evening, after 48 hours of the work-study-work cycle and very little sleep, he had a catastrophic heart attack in the driveway and was clinically dead for several minutes. Only the quick thinking of a neighbor who knew CPR saved him.

Poverty—and religion—shaped my entire early worldview. In the wake of my sister’s death, my parents joined the charismatic movement in Australia—the same movement that produced the Jesus Freaks, in the period of the Billy Graham crusades. We lived in various terrace houses in the vicinity of Kings Cross—places like Darlinghurst, Taylor Square, and Surry Hills—when prostitutes and bohemians occupied those places. (These days, the inner city is fully gentrified.)

My mother wrote music and played the piano. She and my father shared a belief in grace—the idea that one can become a channel of sorts, a funnel through which kindness can enter the world. Our home became a pit stop for people experiencing homelessness and the lost, a place where they could enjoy a bowl of soup and a song or a poem while en route to the Red Cross or the Wayside Chapel.

When I was a tween, we left Sydney and moved to the bush on the NSW Southern Tablelands—the high country, Wedgetail Country—and I still live here.

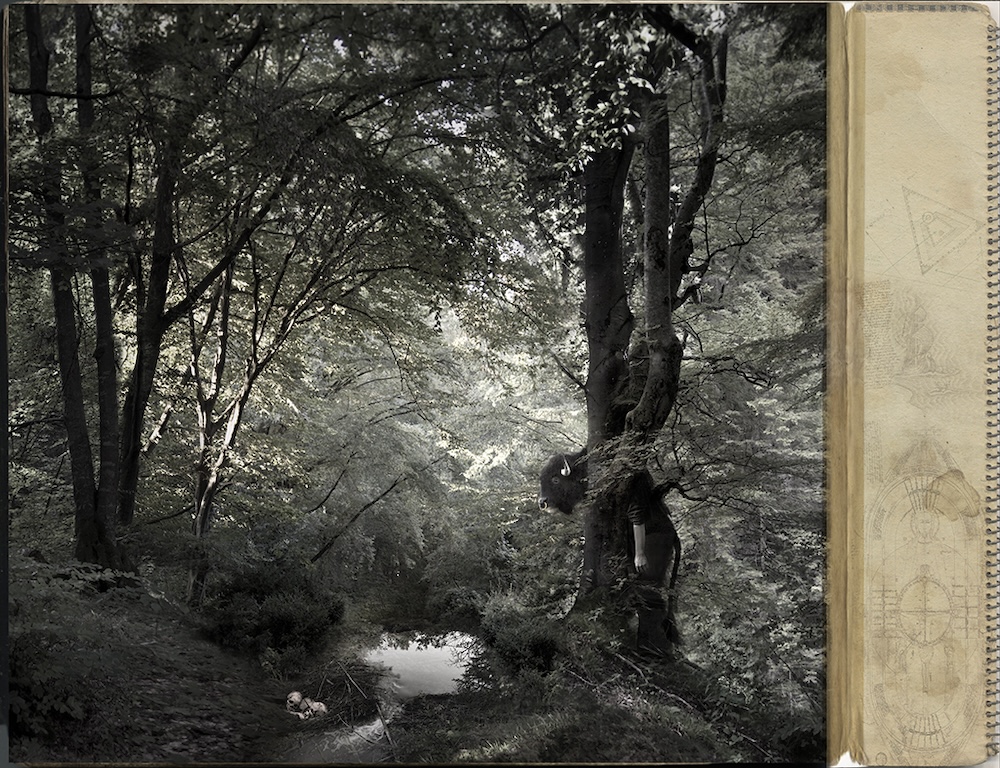

©Judith Nangala Crispin, The Minotaur, with weighted head, disappearing into an erotica of trees (2011) from the series, Marchen (scanned negatives & pages, graphite, india ink and blood; pigment prints on Japanese Gampi paper negative)

DNJ: You are a poet, an artist, a musician. What do you see as the thread between these endeavors? How do they inform each other?

JNC: For me, poetry, art, and music are different manifestations of the same thing. I followed my mother, an excellent pianist, into music school. And I was the only woman in my composition class for the first few years. There has been a patriarchal mentality in fine art, literature, music, and perhaps other art forms that requires creative people to “specialise” and to become a “master” of a single art form. The assumption is that it is impossible to “master” more than one art form. It is also assumed that creativity is under the total control of the one wielding it. But it is not so. Creativity is like a river that surges in one direction for a while, then turns. You either turn with it, or you will be left behind.

At one moment, the river passes through visual art, and at another, poetry. I think women artists have been quicker to recognize this, perhaps because of their long-disparaged “women’s work” such as embroidery, lace-making, and piano playing. Mirka Mora, the well-known and widely loved Australian painter, used to divide her day equally into drawing, painting, and embroidery.

So there is the art form, or the language (which is how I see it), which doesn’t matter much. And then there’s the content, the thing that is said. And that content will, in part, determine the art form that expresses it. Over the past two decades, I have been preoccupied with the idea of Country—what it means to speak to Country and to wait for its reply, what kind of shared syntax is possible with land. And I have tried, in everything I create, which is mainly visual art and poetry these days, to convey two elementary yet profound truths. The first is that all life is equally valuable. The life of a finch is worth the same as the life of a world leader. And the second is that death is not an ending; rather, it is not the ending we imagine it to be. That is, that death is the end of time, but not the end of light.

©Judith Nangala Crispin, Talking to Country (2010) from the series The Cartographer’s Illusion (25mm archival pigment print on silver rag)

©Judith Nangala Crispin, Chair with imaginary crow (2012) from the series Nearly Birds (scanned medium format and 35mm negatives; archival pigment prints on Museo silk rag paper)

DNJ: How do you balance your life given the multiple roles that you hold?

JNC: I get swamped—partly because I’m an obsessive, so my work can take hundreds of hours to complete. And partly because I have to make a living, there’s that struggle too. But I try not to look too hard at the mountain of tasks ahead of me. I try to focus on what’s nearest and get the next thing done. And I enter my studio each day as if it were a cathedral or another holy place. I try never to take creativity for granted. The art world is littered with individuals who call themselves artists but have not completed a work in decades. I never trivialize that.

©Judith Nangala Crispin, Self diptych (2009) from the series The Cartographer’s Illusion (mixed digital and 25mm archival pigment print on silver rag)

DNJ: You identify as what we here in Hawai’i would call “hapa“, or a person of mixed-race and ethnicity. You’ve written a detailed statement about your ancestry, your positions on colonialist erasing of identity, and of finding ways to embrace all of you. As the white mom of a mixed-race child, this is an area of great interest to me. As someone who lives in a land that was overthrown and colonized, I have further interest in the ways Western society has erased native peoples’ cultures and identities. What began you in the search for family history?

JNC: This land is soaked with blood and sorrow. My search for my family’s truth is not mine alone. It is the search of thousands of people. The ones they did not murder were rounded up and put into missions. People with ancestors from the missions were able to find them, because the colonizers kept very meticulous records. Some Aboriginal women became domestic servants, mistresses, and surrogate mothers. In those cases, they would take the surname of the house. Charlotte/Millewa would become Miss Charlotte Clark after bearing a child to the patriarch of the Clark family home. And her children would take that name too.

Until the late 60s, a child could be forcibly removed from their family home if they were up to what they used to call “octoroon” or an eighth Indigenous. Language mattered. At one time, “full-bloods” were considered ‘Aboriginal’ and half-castes “Natives”. Kids were upgraded from “Aboriginal” to “Native” on their 17th birthday, but only if they cut ties with other Indigenous people. Everyone had to sing from the same hymn-book to keep the children safe. Ancestors were erased, or reinvented as Moors or Spaniards, who’d lost their papers at sea. Problem Aunts were lobotomized in asylums. The black market in fake birth certificates, military records, and christenings boomed.

But society morphs and changes. Sooner or later, you have to decide what the truth of your history means to you. Because it’s a risk. And at one point, it became clear to me that the risk of not speaking my truth was far greater than the risk of disclosure. I always knew we had ancestry because my Grandmother told me, my mother told me, and my uncle told me. But I also knew we should never say so. We would never rise out of poverty if people knew. We would not be safe, and our children would also be in danger. But Diana, as I know you know from your Hawai’i experience, you can only live in the shadows for so long.

It’s still dangerous to speak of these things. Aboriginal kids are still being murdered in police custody. People with murky ancestry are publicly shamed on racist websites that still align personal worth with blood quantum. But it is more dangerous to remain silent, to condemn my daughters and grandson to silence.

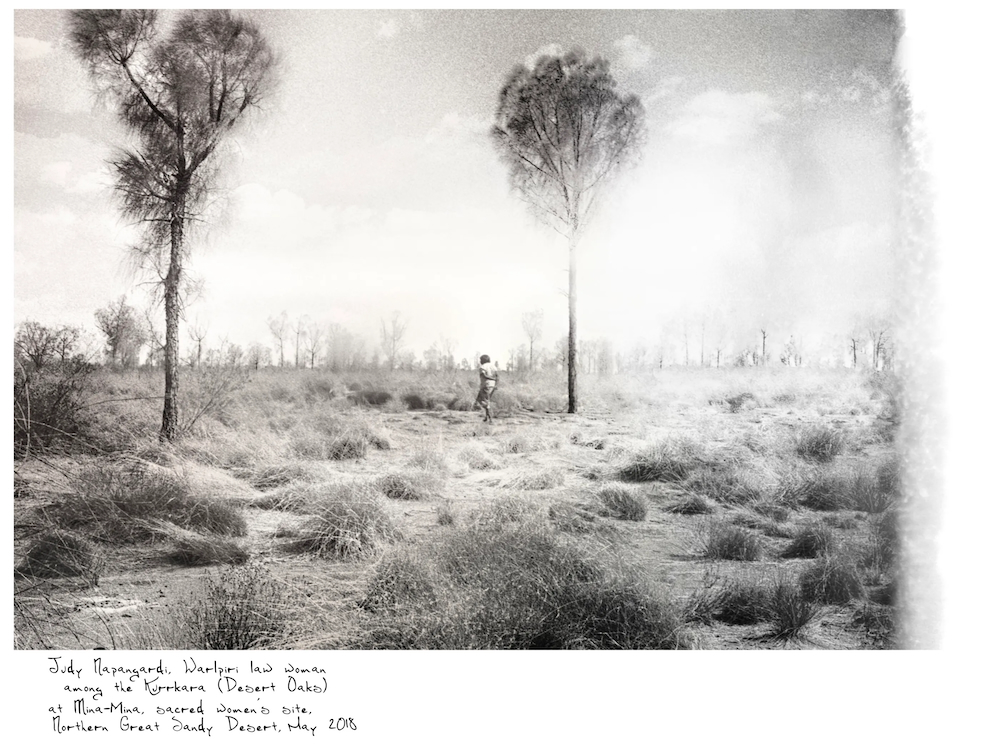

©Judith Nangala Crispin, Mina Mina Sacred Women’s Site (2018) from the series Tanami Desert. (scanned 35mm negative)

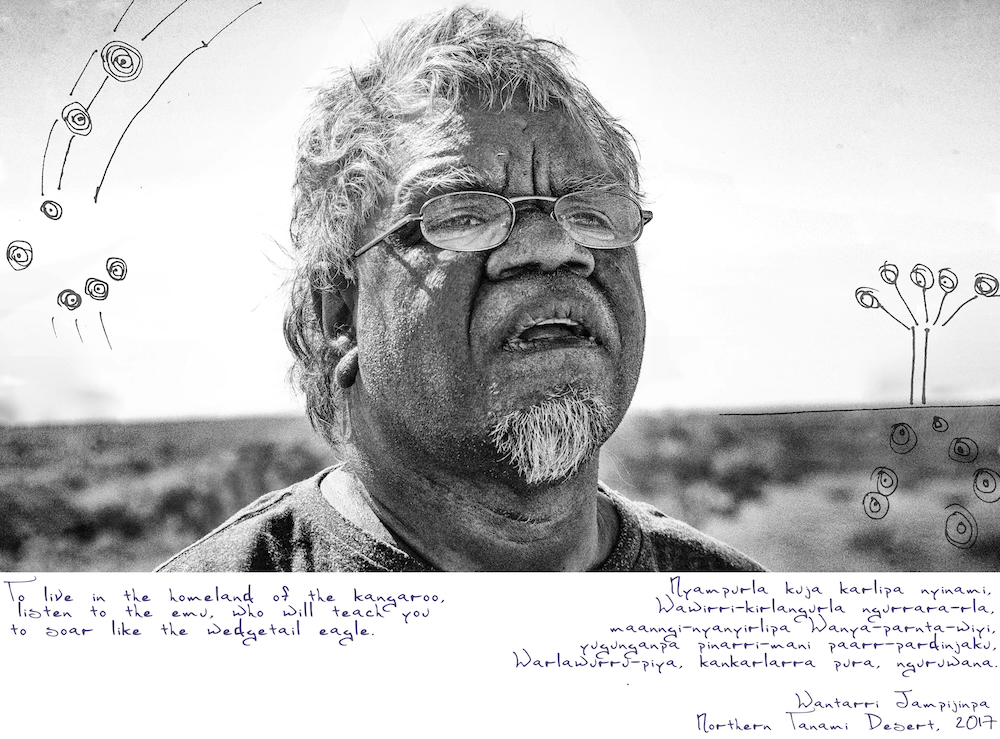

©Judith Nangala Crispin, Wantarri Jampijinpa Pawa- Kurlpurlunu (2018) from the series Tanami Desert. (scanned 35mm negative)

DNJ: Your position on the topic mentioned above and your own identity must surely be present in your work. How does it channel into the resulting final works?

JNC: It underpins all of my work. I fully acknowledge the fact that I have enjoyed privileges that have been denied to many Aboriginal people because my family lied. And because of this fact, I cannot and do not ask for acceptance, for belonging, for the secure Identity of an Aboriginal woman. I will always be a mongrel, a dingo, someone on the edges. So I asked myself what it would mean to belong to Country in the most profound way, without belonging to culture or community. What would happen to someone who did not inherit their belonging, but who forged it directly with the speaking and intelligent land? I spent almost 20 years searching for an answer to this question, devoting months each year to living and working in the Tanami Desert with my Warlpiri friends. And the old people told me “speak to Country, and Country will speak back”. All of my work reflects this. I honor the lives and deaths of animals, birds, and plants, using materials drawn from the land where their cadavers were found. My images are made from light and blood. Light and blood—truth and violence. The reclaiming of history from our colonial past.

Karna Ngunja 92014) The Dark Emu (204) from the project Kurdiji 1.0. (Kurdiji 1.0 is an app created by Warlpiri elders in collaboration with a small group of artists. It is designed to increase resilience in vulnerable Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, and to prevent suicides. The Dark Emu, the black nebula between the pointer stars of the Southern Cross, is sacred to all Australian Aboriginal tribes and nations.)

DNJ: I’m especially curious about how you developed your personalized Lumachrome process (described here.)

JNC: When a deceased animal or bird begins to break down, in the hours after their passing, fluids come out of them. And these fluids, which contain compounds we call “putrescence” or “cadaverine” that kind of thing… also contain a lot of salt. And salt, as we all know, is a developer. So the animal itself, by way of its own decomposition, creates marks on a sheet of darkroom paper. Anyone who has made sun prints or lumen prints knows that the light itself will blacken any part of the paper not covered by the animal. The decomposition process marks the page beneath the animal, and the light marks the page around it. My contribution to this artwork, largely created by Country on its own, is to interfere. I wait as the print develops, and where the liquids pool on the page, I paint them through. Over time, I have accumulated a great deal of knowledge about this kind of chemistry, so I know when a colour is going too far and when a detail will be lost. I create resists on glass to lighten areas, I sharpen edges with a biro, I add ball bearings or marbles to restore an eye (if the crows have taken it first). And at the end of all this, when the print has been made, I wrap the creature in paperbark, in the old way, and place it in a hollow tree. Ultimately, I don’t create these works for human beings. I am not using art to chase money, notoriety, or a career. I make art for these creatures, for the animals and birds that have lost their lives in a world dominated by human interests, human roads, and human pollution. They are elegies for lost miracles. And if people like them, I’m very pleased because it tells me that we are not lost as a species—that there are still people who value the lives of their non-human kindred.

©Judith Nangala Crispin, Enid, connected to Earth by zodiacal light– spider- strings in the old language, the umbilicus of Country (2019) from the series The Dingo’s Noctuary (Lumachrome glass print, chemigram, cliché-verre. Deceased microbat on fibrepaper. Exposed 26 hours under marked perspex)

DNJ: In your statement for The Secret Language of Trees, you write, “Nature studies, some of which will form the basis of a chapbook of images and poems. I take photographs of trees because it helps me to write poetry. Trees teach me to see.” Can you speak more about what you mean by that?

JNC: You know, I wrote that a long time ago—before my time in the desert. In Warlpiri language, the language spoken by my desert friends and adoptive family, the word for “tree” is “watiya”, which means “the ones who watch.” The trees see. Human beings talk. We talk and we talk until the only thing we hear is our voices, until the only thing we see is our reflection. But sometimes, for instance, after fire—when the skin of the ghost gums is pure white against the charred hills, and their leaves have been burnt to copper—sometimes the sheer beauty of that is enough to shut us up. And then we look. And we see. No human being has ever made an artwork that can do that.

©Judith Nangala Crispin, The white trees, the black trees (2017) from the series The Secret Language of Trees (scanned 35mm negative)

©Judith Nangala Crispin, the sunline (207) from the series The Secret Language of Trees (scanned 35mm negative)

DNJ: Where do the ideas you work with come from? Can you share your approach to creating the work?

JNC: I used to work with ideas. A long time ago now. I deified thought. I reasoned that thinking would save me, would save all of us, deliver us from barbarousness, from violence. However, despite all these millennia of thought, we have not been saved. All thought does is create more noise. It anchors us in time, in illusion, in pictures of ourselves that we have made. I don’t want anything to do with thought now. I want to see, to hear, to respond only to what is nearest—the next thing. A neighbor brings me a thornbill that has flown into her window. My only aim is to honor that little life, right now, with whatever materials Country has provided—leaves, ochre, wax. And to do this without expectation of a result. Photographers are excellent at not expecting a result; we know that 40 frames might yield one good photo. And it’s the same with camera-less work. I get one “successful” print for every 90 failures. But each image, good or bad, is moving me in a particular direction.

Without giving it active thought, the work evolves. I don’t know why. However, when I look back over my practice, I can see that the details are more pronounced, the backgrounds are more complex, and the materials are more integrated. Yet, I have never forced this or tried to make it happen. When you truly commit to a practice of stopping trying to say everything (portraits, landscapes, buildings, etc.) and entirely focus on saying only one thing, it is like planting a seed. And that seed begins to grow by itself. Every time you show up in the studio, you are watering that seed. And you water it, and water it, and one day it has changed into a seedling, then a plant, then maybe even a tree.

©Judith Nangala Crispin, Remembering Fred Williams, in Arthur Boyd’s garden (2018) from the series The Dingo’s Noctuary (Lumachrome glass print, cliché verre. Leaves, seeds and sticks on fibre paper. 18 hours under marked glass in winter light.)

©Judith Nangala Crispin, Olibart had not been in a body long, so when he dropped his form, in a blaze of oncoming traffic, he stretched himself gloriously across the night sky in Vulpecula, sacred constellation of foxes (2020) from the series The Dingo’s Noctuary (Lumachrome glass print, cliche-verre, chemigram. Road-killed adolescent red fox, dandelion seeds and sand on fibre paper. Exposed 36 hours under marked perspex in a geodesic dome)

DNJ: What do you do when encountering a period of creative block? How do you work through it?

JNC: My feeling is that you have only been blocked when you are delivering a monologue. If I am wondering “what should I say to these people? And will it be good enough?” then of course I will be blocked. But if I am responding to something, it is different. You will say to me, “Judith, what does God look like?” and I will answer, “Diana, God is a blue horse.” Monologue is the problem.

©Judith Nangala Crispin, Die Wilde Jagd (2011) from the series Marchen. (scanned negatives & pages, graphite, indian ink and blood; pigment prints on Japanese Gampi paper)

DNJ: The battle for women photographers/artists to receive equal recognition in the art world is still ongoing; museums continue to hold more works by men, and the more well-known galleries still exhibit more work by men than by women. I am going on a limb and saying you may face a double whammy with colonialist thinking and the patriarchy coming in at once. Do you have any thoughts about this?

JNC: Fuck them. If they only want to see ‘white man’s art’, then maybe it’s all they deserve. The elite classes are under siege all over the world. Increasingly, the dominant culture is crumbling. We cannot allow our work to be shaped by other people’s priorities, insecurities, or need to control and own everything. We must continue to speak the truth, not truth to power, but truth that transcends power. Ultimately, our strength lies in our ability to communicate. In the past, that ability was controlled by those who owned the platforms—gallerists and festival directors. However, we now have the internet, so we are free. Every time I post an image, it is seen by other women, as well as people from diverse cultures and communities. Every image I post permits them to speak too. That’s what real power looks like. It’s the power to empower others. Patriarchy doesn’t understand that kind of power. It never has. It must overpower others; the strength of patriarchy depends on others having less power. The age of the patriarch is over. I have always made art without the slightest interest in how it is received in the halls of power. Truth is the only weapon we have. We have to use it.

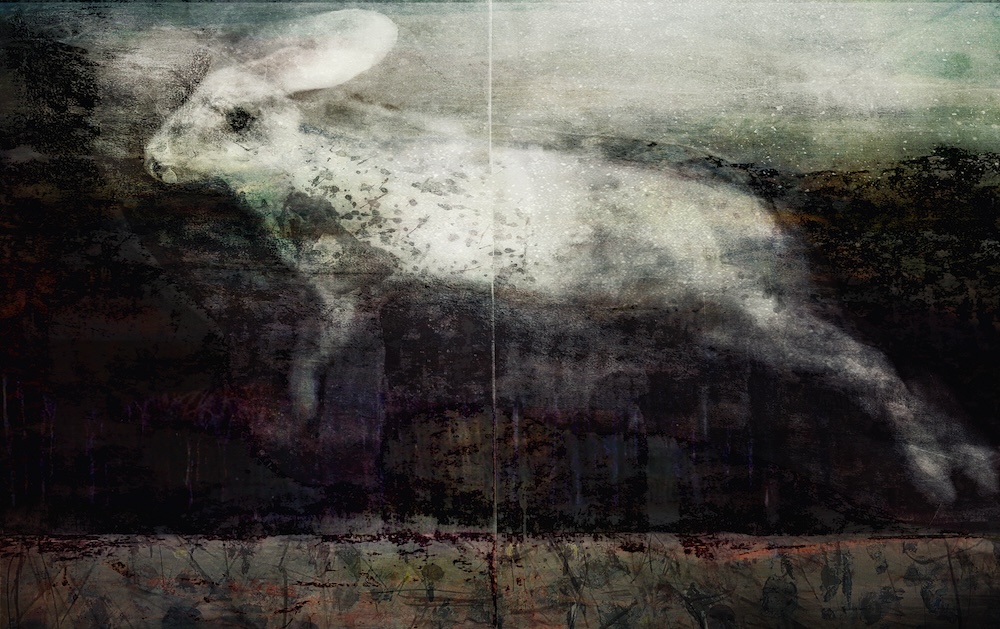

©Judith Nangala Crispin, Peter Lapin, looking for Wittgenstein in the afterlife (2018) from the series The Dingo’s Noctuary (Lumachrome glass print, cliché verre. Roadkill rabbit, blood, sticks and grass on two pieces of fibre paper. Developed 32 hours under marked glass, back of the ute in winter light and moonlight.)

DNJ: It seems that one of the great battles in photography is between those who believe their work should speak for itself and hence don’t write, and those who think writing can offer an entry point to the work for viewers who don’t find it, as well as underscore the artist’s ideas for those who do. What camp do you fall into and why?

JNC: It’s tricky, isn’t it? Because photography is an art, even when we refer to it as something different, like reportage, it remains an art. And the writing we usually put beside it is rarely art. I don’t need a caption under a picture of a rabbit that says “rabbit”. We’ve all seen contributions by photographers ensnared by academia—one photo of a cloud accompanied by a ten-page essay on the metaphysics of clouds. It’s upside-down. The emphasis is on the wrong thing—the forensic science of art dissection, and not on art. So, from that perspective, I am firmly in the no-writing camp. However, when the writing is also an art, I take a different view.

Consider something like opera, which combines music, visual art, dance, literature, and design. It works because all the elements are striving toward the same expression. A prescriptive analysis is fundamentally anti-art; it leaves no room for the viewer’s interpretation and implies that the viewer is incapable of understanding the image—it contributes no vision of its own. So, where a picture of a rabbit with the caption “rabbit” is patently stupid, it’s different if the caption beneath the rabbit reads “God is a blue horse” because it shapes how we see the rabbit, without telling us how we should see it. When images, writing, music, dance, embroidery, and taxidermy are all art, then why wouldn’t you combine them?

©Judith Nangala Crispin, When Richard was ready, magpies sang at his hospital window until he remembered wings (2019) from the series The Dingo’s Noctuary (Lumachrome glass print, cliche-verre,

©Judith Nangala Crispi, Stella weaves songlines across the darkness of space (2019) from the series The Dingo’s Noctuary (Lumachrome glass print, chemigram, cliche-verre. Asian Koel, fallen in a poet’s garden, sand, vegemite, ballpoint pen and marker, on fibre paper. 32 hours under marked perspex in cold, wet conditions.)

DNJ: What is influencing your work lately? Please tell us what you are working on now.

JNC: I’ve been working with an Australian sculptor and painter on a book of images and poems about angels and angel-like beings. We have several cryptids in Aboriginal mythology that are similar to angels but without the moral superiority. It’s very early days, but I’m excited about the work.

©Judith Nangala Crispin, In Joan’s garden, she slipped off her feathered gown, and left it folded in wildflowers – a last gift (2018) from the series The Dingo’s Noctuary (Lumachrome glass print. Fallen magpie (from Joan’s garden), salt, resin, wax and chemicals on fibre paper. 26 hours under perspex. Remembering Fred Williams, in Arthur Boyd’s garden. The Dingo’s Noctuary 2018 Lumachrom

©Judith Nangala Crispin, After the headlights, Jessica opened her eyes and lifted, through clouds, to the country of her ancestors (2018) from the series The Dingo’s Noctuary (Lumachrome glass print, cliché verre (cropped and framed), roadkill possum found in Newcastle by my sister in law and frozen, transported back to Wamboin in an eski. Brushed with saltwater and exposed 42 hours on a glass sheet, marked with paint and wax (cliché verre), on fibre paper in perspex housing)

DNJ: What’s coming on the horizon for you?

JNC: On October 1st, Puncher & Wattmann Press will release my new book, The Dingo’s Noctuary, a gigantic illustrated verse novel featuring camera-less Lumachrome prints, hand-drawn maps, plant pressings, poems, prose, and star charts. It took me six and a half years to write, during which time I crossed the desert 37 times—sometimes alone, sometimes with the dog on the back of the motorcycle. That same month, I’m exhibiting at the Lithuania Photography Festival. I’ll be busy!

©Judith Nangala Crispin, The Tree of Joyfulness erupts from the marrow of the First Rat. And its humming branches call the spirit rodents, those lost or returning to the source, and offers them shelter (2025) from the series The Dingo’s Noctuary. (Lumachrome glass print, cliche-verre, chemigram, drawing, scan. Pressed kangaroo paw, dehydrated bush rat, five frost-killed marsupial mice with seeds, household chemicals, copper chloride, crayon, wax, vegemite and graphite on fibre paper. Exposed 37 hours in a greenhouse)

Thank you ever so much, Judith, for your thoughtful and provocative responses to my questions. I’ve been following this work for the past several years, yet I had no idea how you created it or the the deeply meaningful cultural touchstones it referenced. I look forward to seeing how your work continues to evolve.

Readers, I hope you enjoyed learning about Crispin’s work. Judith has also published a collection of poetry, The Myrrh-Bearers (Sydney: Puncher & Wattmann, 2015), and a collection of photographs and poems made with the Warlpiri, The Lumen Seed (New York: Daylight Books, 2017). Her third, and most extensive book, The Dingo’s Noctuary, is available for pre-order here.

©Judith Nangala Crispin, After the highway, the lights, the cool dark wind that moved him, Murat, somewhere in that gigantic night, discovered a door (2025) from the series The Dingo’s Noctuary. (Lumachrome glass print, cliche-verre, chemigram; road-killed Quokka, with ochre, wax, vegemite, pollen, bark, seeds and sand. Exposed 2 hours in WA ,26 hours in NSW in a perspex box)

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The Female Gaze: Anne Berry – Ode to the Blue HorsesNovember 13th, 2025

-

The Female Gaze: Lara Gilks – Just Outside the FrameOctober 23rd, 2025

-

The Female Gaze: Jane Szabo – Recent WorkSeptember 21st, 2025

-

The Female Gaze: Karen Klinedinst – Nature, Loss, and NurtureAugust 23rd, 2025

-

The Female Gaze: Judith Nangala Crispin – A Committed PracticeJuly 31st, 2025