Diana Cheren Nygren: Mother Earth

So many projects from Diane Cheren Nygren have stuck with me over the years. I believe I was first introduced to her work while researching imagemakers working with history and family, finding her earlier series “The Persistence of Family.” While many artists have combined older images with contemporary people and places, the way Diane was able to balance the two was a successful balance between the subjects and eras. She balances these contrasts again in “Mother Earth,” focusing on the natural landscape and human interaction. By creating these small worlds within a larger landscape, recalling sublime views from the Romantic era, the viewer is forced into acknowledging their own activity in contrast with the vastness of the natural world. I am particularly drawn to Diane’s attention to detail, thinking about the frame and its integration into the images and gallery. I cannot wait to see where she takes this series from here.

Diana Cheren Nygren is a photography based artist located in Boston, Massachusetts. Her work explores the relationship of people to their physical environment and landscape as a setting for human activity. She was trained as an art historian focussed on modern and contemporary art, and the relationship of artistic production to its socio-political context. Diana’s photographic work is the culmination of a life-long investment in the power of art and visual culture to shape and influence social change, addressing serious questions through a blend of documentary practice, invention, and humor.

Her project “When the Trees are Gone” has been featured in numerous publications and has been shown in galleries and museums worldwide. Among the awards won for this project are Discovery of the Year in the 2020 Tokyo International Foto Awards, 2nd place in Fine Art/Collage in the 2020 International Photo Awards, as well as being a finalist for Fresh2020, Urban2020, the Hopper Prize, and OpenImage Barcelona.

The project “The Persistence of Family” has been shown across the globe and was awarded a Lensculture Critic’s Choice Award, Best New Talent win the 2021 Prix de la Photographie, Best of Shoot in the 2021 London International Creative Competition, 2nd place in the International Photo Awards, and has appeared in numerous publications. In Spring 2022 “The Persistence of Family” was featured in solo shows at the Soho Photo Gallery and at the CICA Museum in Gimpo, South Korea, and October 2024 was exhibited in Singapore.

Follow Diana on Instagram: @dianacherennygrenphotography

Mother Earth: Nevertheless She Persisted

A city girl and skeptic to my core, I feel an overwhelming sense of awe in the face of a desert spread before me or the expanse of the ocean. Within these magnificent landscapes, humanity seems small and insignificant. Geologic eras are etched into layers of rock and our time on earth seems short in contrast. So far there have been thirty-seven epochs in the history of this planet. Humans have been on Earth for less than two of these, though our impact on the shape of the planet has been tremendously outsized. What will the next epoch look like?

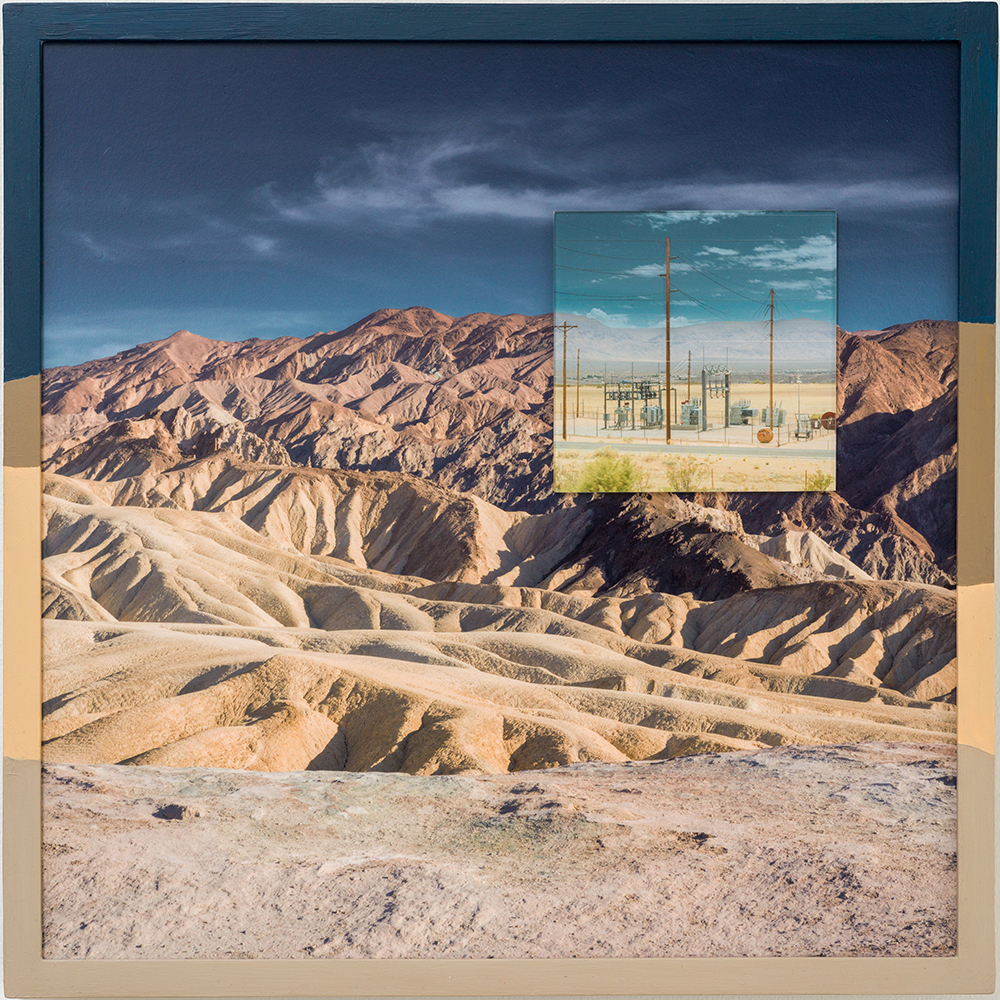

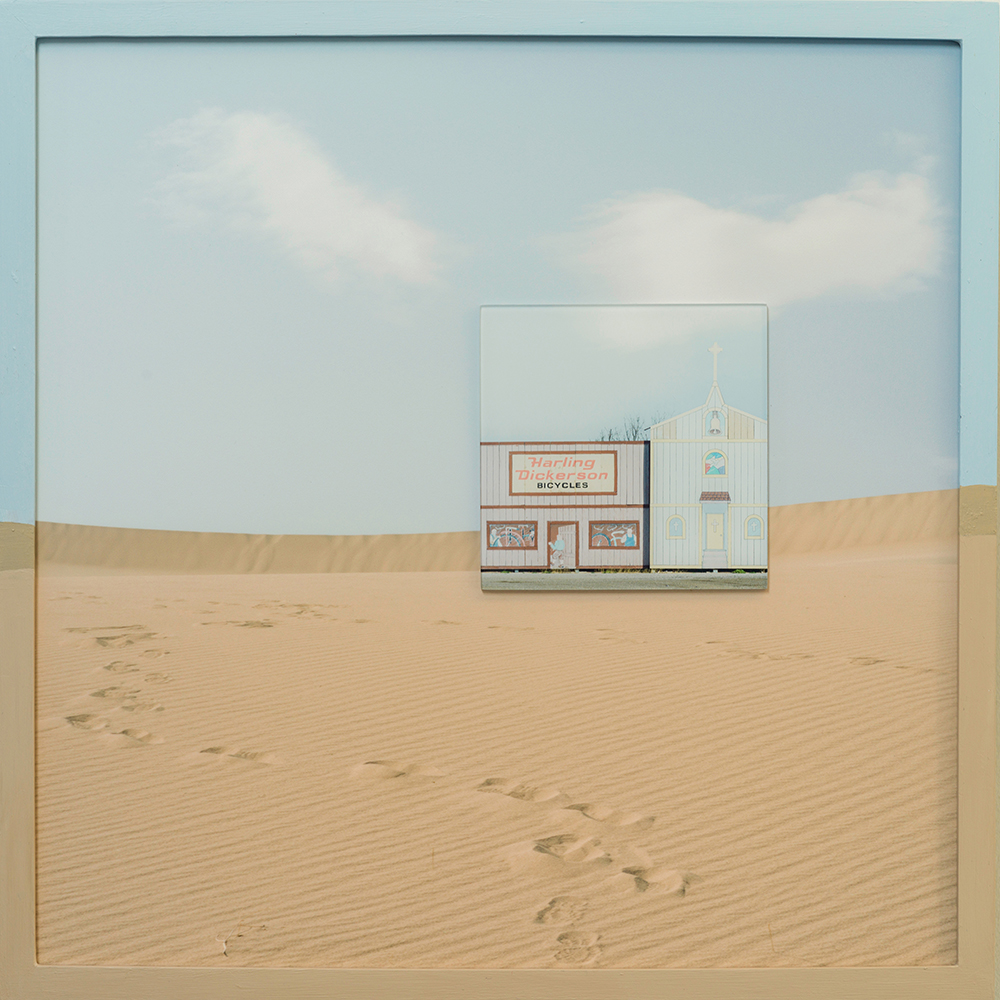

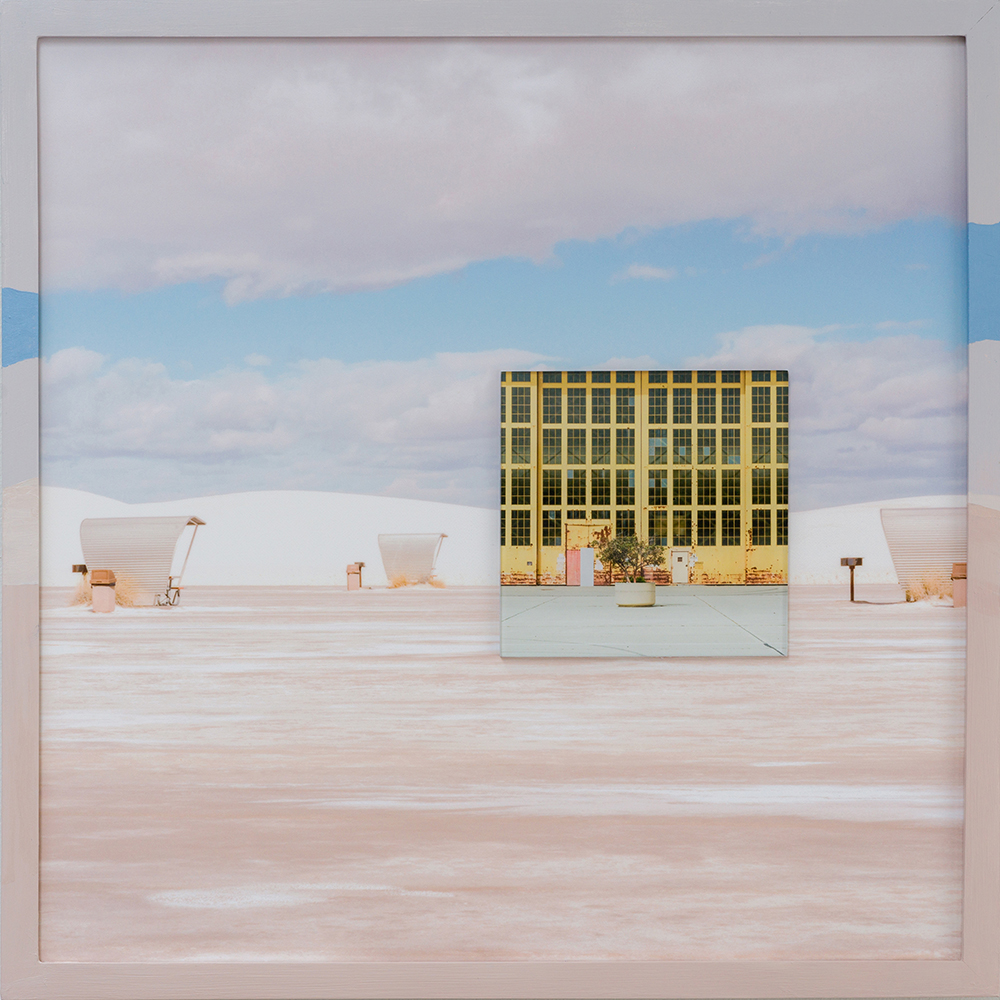

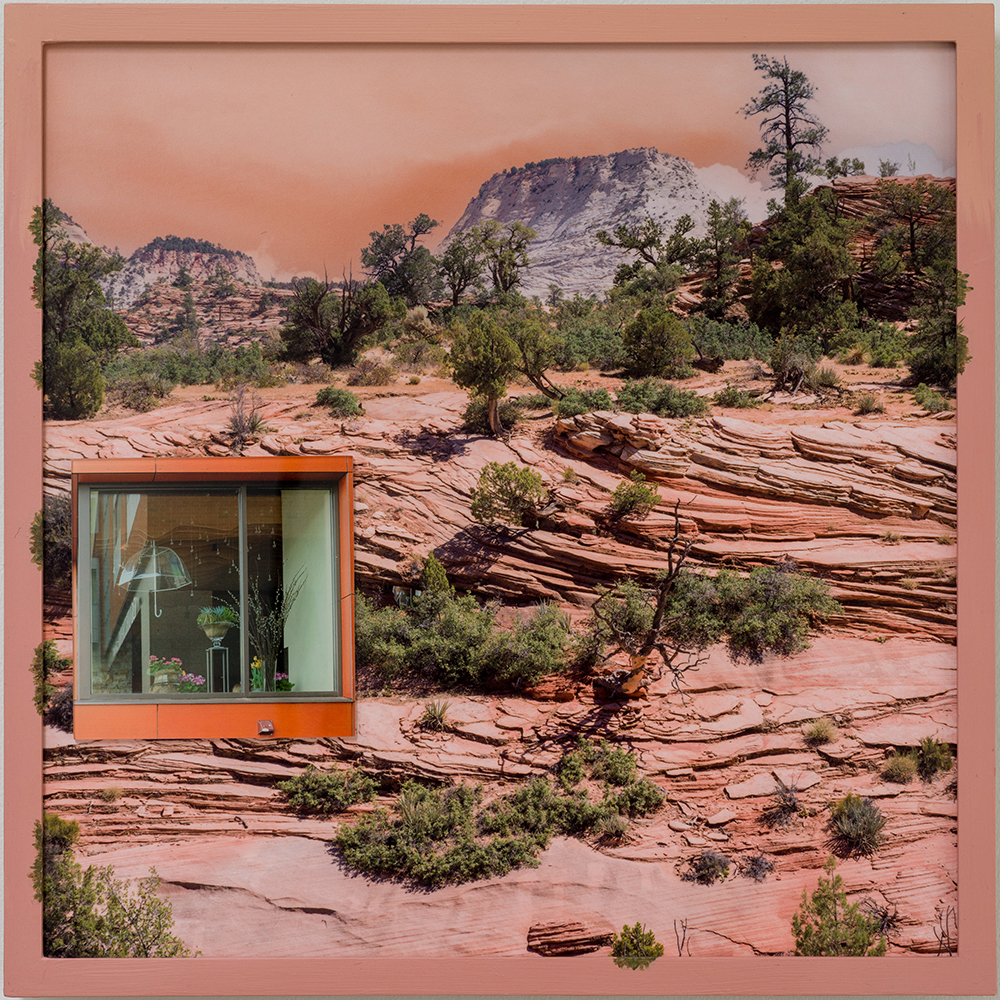

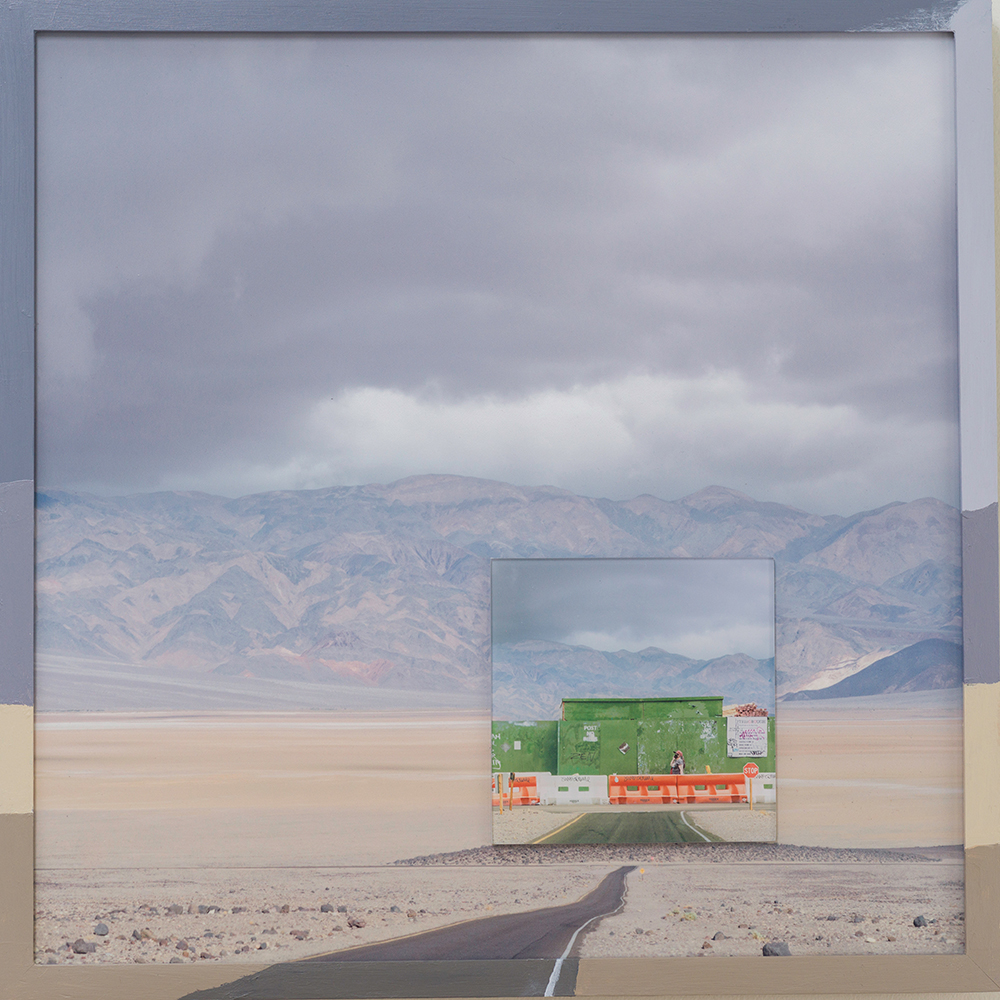

I have mounted scenes of human habitation behind acrylic, plastic walls that we imagine can safely separate the things we do from having an impact on the natural world. I have then affixed these scenes onto and within sweeping landscapes. I am presenting this work without glass. The constructed world behind the acrylic is literally protected, while the landscapes remain exposed and vulnerable. A continuity of line and color between these two parts of the work hints at their interconnectedness. I use the desert southwest of the United States as a stand-in for what the majority of the land on our planet might look like as it continues to be shaped by rising temperatures, drought, and fires. Ultimately, I present these multi-layered images in hand-painted wooden frames, alluding to the next chapter in the planet’s history. As the image pushes beyond its edges, the story continues to evolve.

In spite of human activity, the Earth continues to transform and reinvent itself. The Earth is not coming to an end. Its inhabitants cannot escape its permanence, and the power it has to shape their existence. The question remains, as nature reinvents itself, can we adapt with it? Will we be part of that next chapter?

This work will be exhibited in the 5th edition of Rencontres de la photographie à Dakhla in Marrakesh in November.

Epiphany Knedler: How did your project come about?

Diana Cheren Nygren: It was really the landscapes themselves that dictated the series. Never having spent much time in the southwest, driving through the region, staying in the desert, taking in the vastness of the landscape, made a profound impression on me. As I tried to define that impression and the thoughts it raised, the basic idea for this project emerged. I had a clear idea of what I wanted to communicate fairly early on in developing the project, but finding the physical form to communicate that effectively was a challenge. Initially I was compositing the people going about their daily activities into surreal desert landscapes. From there I tried inserting the scenes of human habitation into desert landscapes, outlining them, almost as if they were map details once you zoomed into what was happening in the desert. After a lot of feedback and discussion, it became clear that I did not want to imply that people were living their lives as usual on a future parched planet, but that how we would live successfully in that environment remained unknown – that was the challenge the work was presenting to the viewer. How are we going to adapt and change the way we live from what we are accustomed to work in this future setting? I spent a lot of time thinking about the materials I was using in the project, knowing that the work was driven by an awareness of environmental concerns but printing photographs is not particularly an environmentally friendly process. Ultimately, the acrylic “encasing” and mounting of the current scenes worked both visually as a way of enabling them to be simultaneously distinct from and continuous with the larger landscapes, as well as metaphorically pointing to the problematic nature of plastic and standing for the bubble in which we tend to live.

As a child I distinctly remember my parents asking us to admire the beauty of nature. This annoyed me to no end. I couldn’t conceive of anything more boring. So I was shocked to realize decades later how much I was drawn to nature, how long I could spend simply looking at clouds, and how much taking in the sky or the ocean seemed to enable me to breathe in a way that I didn’t on a daily basis. Photography became a vehicle through which to slow down and take it in, to share my awe for nature, precisely what my parents had tried to do with so little success when I was young. And the fact is that I love city life and will always choose city living, and at the same time it makes me urgently aware of the value of nature and undisturbed natural places. Modern life, it seems to me, is about being able to hold these two ideas at the same time, and hopefully that’s what much of my work as a photographer talks about.

EK: Is there a specific image that is your favorite or particularly meaningful to this series?

DCN: I don’t particularly have a favorite image in this series. The various pictures I think have different strengths. In some I love the colors and composition, and in others I think there is a strong narrative. But as I write this, for some reason “Methane Gas” came to mind. I think largely because there is nothing particularly human even in the inset image. The protagonists are cows and they are producing the harmful gas. And yet it is how we farm and breed them, how we use what may occur naturally and alter it to fit our needs, that has made the sheer abundance of cows such a problem.

EK: Can you tell us about your artistic practice?

DCN: For many years I resisted post-production, but at this point it has become central to my work. I was trained on film, and was wedded to the idea that the frame exactly as it was first captured in the camera is absolutely sacred. Photographs capture what we see, so is it really legitimate as a photographer to change that? But I came to realize a couple of things. Of course photography does not in fact capture reality – it is always partial, always constructed, and always just one point of view. With digital images we can play with color in post-processing, but it’s not as if the colors with film were in fact “accurate”. Different cameras and brands of film render color entirely differently. And once you acknowledge that, I think there’s no reason when working with digital images to play with color in post processing to get it “where you want it”. I also want there to be a relationship between the artwork itself and the medium used. What distinguishes photography from other media? Our initial response to a photograph is to believe that what is in it actually existed in a physical way. AI is obviously throwing a huge monkey wrench into that. We know that people have manipulated photographs to some extent for ages, but It has now become nearly impossible to believe in the photograph as evidence of anything. But as of now at least that instinct remains. So I stopped thinking of that relationship as sacred and inviolable, and started to think about that instinct as something that a photographer as an artist can use.

Playing on that instinct on the part of the view, my work makes visible and gives a concrete form to something impossible, or perhaps imagined, and uses that to tell a story. With post-processing you can make something that isn’t real feel real, and therefore give form to ideas and possibilities. I don’t want to make images that trick the viewer in any way. The initial response is shaped by the instinct to believe what you see in a photo, but I also want the viewer to ultimately be able to see the ways in which the image was constructed and to understand it as a construction, so I try to use post-production in a way that at some point makes itself known to the viewer. I may have a story in mind while making the images, but making their constructed nature visible makes a space for the viewer to see that story as a question, and to come to independent conclusions about it.

EK: What’s next for you?

DCN: For the last couple of years I’ve been developing a new body of work that grows out of an interest in and travel to South Korea. I was initially drawn to the Korean popular culture that gets exported to America – mostly films and television shows – and then began to learn the language and study Korean history and culture. But nothing could prepare me for the degree to which I absolutely fell in love with the country once I got there. While I was there I didn’t shoot with anything particular in mind, but when I got home I sat down with the thousands upon thousands of frames I had shot and tried to work out what story they were telling me. They say in English “the grass is always greener on the other side”, and when travelling it is certainly easy to see what is good and overlook what is not. But the reality is also that I can only relate to a place I visit as an outsider and a tourist. I try to understand the culture and immerse myself in it as much as possible, and to look with an open mind, but ultimately I can’t make a project that captures South Korea in all of its complexity. But what I brought home with me, and what I could do, is try to capture the aspects of South Korea and South Korean culture that as an American I found so seductive. What about it made me happier there than I generally am at home, made me eager to get out of bed and engage with the world? And so, what did I notice as distinct and different from my environment in the United States (and other places I have traveled), what was I getting or what need did I have that was somehow being filled there but not at home? The project that has come out of that, is my attempt to give form to some of the answers to those questions. One of the things that intrigued me from the beginning was the incredible global influence that South Korean culture has at this moment in time, especially in light of its history and its relative size. That suggested to me that what I was trying to capture in this work wasn’t just limited to my own experience, but touched on something larger that many people from a variety of places are finding compelling. In terms of form, the work is still very much me and consistent with what I have done in the past. But in terms of my relationship to the subject matter, it is unlike anything else I’ve done, and there’s definitely a lot of anxiety that comes with that. Someone suggested to me that being in South Korea feels to me like “a warm hug” and I think that’s an apt description, and hopefully that’s in this work. It is not my place as a foreigner to offer a critique on South Korea. Instead, what I can do is try to understand what I can learn from it, and even what it can teach me about where I came from.

Epiphany Knedler is an interdisciplinary artist + educator exploring the ways we engage with history. She graduated from the University of South Dakota with a BFA in Studio Art and a BA in Political Science and completed her MFA in Studio Art at East Carolina University. She is based in Aberdeen, South Dakota, serving as an Assistant Professor of Art and Coordinator of the Art Department at Northern State University, a Content Editor with LENSCRATCH, and the co-founder and curator of the art collective Midwest Nice Art. Her work has been exhibited in the New York Times, the Guardian, Vermont Center for Photography, Lenscratch, Dek Unu Arts, and awarded through Lensculture, the Lucie Foundation, F-Stop Magazine, and Photolucida Critical Mass.

Follow Epiphany on Instagram: @epiphanysk

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Margo Ovcharenko: OvertimeJanuary 27th, 2026

-

Yumi Janairo Roth: EFFIGY 1462January 20th, 2026

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026

-

Salua Ares: Absense as FormNovember 29th, 2025