Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Tariq Zaidi (2015) and Astrid Reischwitz (2016)

Photolucida is a Portland-based nonprofit dedicated to providing platforms that expand, inspire, educate, and connect the national and international photography community. Critical Mass, Photolucida’s annual online program, is designed to foster meaningful connections in the photography world. Open to photographers at all levels, anywhere in the world, participants submit a portfolio of 10 images. Following an initial pre-screening, 200 finalists are selected to have their work reviewed and voted on by up to 200 distinguished international photography professionals. From this process, the Top 50 are chosen, and a range of awards is presented. Submissions open each June.

In 2025, we celebrate the twentieth year of announcing the Critical Mass Top 50 finalists! We are honored to partner with Lenscratch to reflect on this history through a special series highlighting two artists from two different years in each post. Each featured artist offers a window into the diversity of projects and voices that make up Critical Mass—from documentary and narrative photography to conceptual, photo-based practices. These Q&As share the history, intention, and trajectory of the artists, pairing their Critical Mass portfolios with newer work.

For Critical Mass 2025, we received submissions from artists across 26 countries, tackling subjects in countless styles—from black-and-white and digital photography to chemigrams, cyanotypes, photographic sculpture, and textiles. Our esteemed jurors, representing a wide range of global perspectives, dedicate their expertise and thoughtful consideration to this process, often leaving feedback and encouragement for the artists.

Critical Mass continues to elevate emerging photographers, providing a platform that amplifies their voices to broader audiences and to the industry professionals who help shape careers. We are deeply grateful to everyone who makes this possible.

Tariq Zaidi 2015

When Tariq Zaidi left his career in the events business in 2014 to pursue photography full time, he committed himself to documenting lives and communities often overlooked by mainstream narratives. In this conversation, Zaidi reflects on his early recognition by Photolucida Critical Mass Top 50, his seminal project The White Building in Cambodia, and his long-term work with the Sapeurs of the Republic of Congo.

Tariq Zaidi is a freelance photographer based in the UK who gave up his executive management position in an events business in 2014 to pursue his passion for capturing people’s dignity, strength, and soul in their environments. Tariq’s photography showcases a deep commitment to documenting significant social issues, systemic inequalities, cultural traditions, and communities facing endangerment or marginalization on a global scale. Tariq independently assigns, funds, researches and writes his own work.

In September 2020, Zaidi published his first book, Sapeurs: Ladies and Gentlemen of the Congo, which has received extensive recognition for its photography. The book was highly praised and selected as a finalist in the “Photography Book of the Year 2020″ category by Pictures of the Year International, a prestigious photography competition. In September 2020, the book’s work was showcased at the Visa Pour L’image International Festival of Photojournalism. Later that year, “Sapeurs” received further recognition and was included on Vogue’s exclusive list of “Best Fashion Books of the Year 2020″. In 2022, the book continued to gain acclaim and was named a finalist for the “Lucie Photo Book Prize” while also receiving a nomination for the “African Photobook of the Year Award”. The book was designed by Stuart Smith, published by Kehrer Verlag Germany, and co-edition with Seigensha Art Publishing, Japan. It has since gone into its second printing.

Tariq’s second book, Sin Salida (No Way Out), was published by GOST Books, UK in October 2021. The book documents the devastating impacts of the notorious Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and Barrio 18 gangs on El Salvador. Through depicting the gang members, police, murder sites, funerals, and the government’s efforts to combat the gangs, Zaidi illustrates the control these groups have over Salvadoran society, the violence through which they operate and the grief and loss resulting from the violence. Tariq’s commitment to human rights was recognised when his work on El Salvador earned first place in the Photojournalism Category at the 2020 Media Awards by Amnesty International. The photo book was also honoured with a first prize from the IPA (International Photography Awards, USA) in 2022 and was named a finalist for the Lucie Photo Book Prize. In March 2023, the book was chosen as a finalist in the “Photography Book of the Year” category by Pictures of the Year International.

Tariq Zaidi’s third monograph, North Korea: The People’s Paradise, was published in November 2023, by Kehrer, Germany. This compelling work unveils North Korea, often obscured by Kim Jong Un’s regime and state propaganda, through a vibrant, humanistic lens that transcends politics. In a world where most insights are superficial, Zaidi’s photography delves deep, capturing the nation’s intricate essence. Annually, approximately 5,000 non-Chinese tourists visit North Korea under strict regulations and photography restrictions, but Zaidi’s candid images break through these barriers, illuminating the everyday lives of North Koreans and the complex tapestry of their society. After three years of meticulous research and photography, this book challenges stereotypes and invites readers to gain a fresh perspective on North Korea. Featured in the New York Times Book Review and honoured as a NYTimes Editor’s Choice, its first edition quickly sold out, with a second printing scheduled for 2024. In September 2024, the book was awarded first prize in the Book Documentary category at the International Photography Awards (IPA), USA and in November, was chosen as a finalist for the Lucie Photo Book Prize.

Tariq’s photography has gained international recognition, with his work appearing in over 1000 publications across 90 countries. His work has been featured by prominent names such as the BBC, The Guardian, The New York Times, National Geographic, Washington Post, Newsweek, CNN, Spiegel, Stern, El Pais, GEO, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Chicago Tribune, Suddeutschen Zeitung, Zeit, Welt, Sydney Morning Herald, Vogue, Marie Claire, GQ, Esquire, Global Times China, Internazionale, VICE, Deutsche Welle, Corriere della Sera, National Geographic Traveler, Conde Nast Traveler, British Journal of Photography, Hindustan Times, Al Jazeera, 6Mois, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Independent, China Daily, Telegraph, Foreign Policy Magazine and Times of London and more. His work has led him to document stories in some of the most challenging environments, demonstrating his dedication and resilience. His coverage spans a diverse range of countries, including Afghanistan, Angola, Brazil, Cambodia, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Georgia, Haiti, Indonesia, Lebanon, Mongolia, North Korea, Republic of the Congo, Sierra Leone, South Sudan and Yemen. These stories, images, and videos have appeared in magazines, online, and on television, showcasing Tariq’s talent for capturing and presenting thought-provoking content to a global audience.

Tariq Zaidi is a highly-regarded photographer who has earned numerous accolades for his photography. With over 80 international photography awards to his name, Tariq’s work has been acknowledged by industry leaders such as Pictures of the Year International, Sony World Photography Awards, Lucie Photo Book Prize, IPA, NPPA, PDN, UNICEF, and Amnesty International’s Media Awards. His work has been recognised eleven times by Pictures of the Year International, including awards in the Premier categories of “Photographer of the Year International,” “Photography Book of the Year” (twice), and the “World Understanding Award.” The IPA named Tariq as one of the “Top 10 Travel Portrait Photographers” in 2016, and in 2018, he was honoured with the Marty Forscher Fellowship Fund for his exceptional humanistic photography by PDN and Parsons School of Design. Additionally, he was nominated for the Prix Pictet in 2019. Tariq’s work has been displayed in over 90 international exhibitions, and he has completed projects in 25 countries across four continents.

Tariq is actively engaged in various projects, including his long-term personal project, “Capturing the Human Spirit,” which showcases hope, dignity, and community through images from the poorest regions of the world. In 2018, the first three chapters from Haiti, Brazil, and Cambodia were shown at the Visa Pour L’image International Festival of Photojournalism.

Tariq Zaidi is a self-taught photographer with an M.Sc. from University College London (UCL). He is represented by Zuma Press, Caters News Agency and Getty Images, and is an alum of the Eddie Adams Workshop. His passion for education led him to teach courses on photojournalism, documentary photography and advanced photography at renowned institutions such as Central Saint Martins and London College of Communications. Tariq is a frequent speaker at conferences, seminars and universities and is constantly searching for unique images and stories through his travels.

Instagram @tariqzaidiphoto

Q: Can you tell us how you first learned about Photolucida’s Critical Mass, and what motivated you to enter?

TZ: After leaving the events industry in 2014, I threw myself completely into photography. One of my first projects was in Cambodia, which became an early published work. When I shared it at portfolio reviews, several mentors urged me to apply to Critical Mass. They described it as one of the most respected platforms for emerging photographers—highly valued across the industry. Their encouragement convinced me to submit a small series, which was ultimately recognized.

Q: Your 2015 Top 50 portfolio, The White Building, is a compelling document. Can you explain the origins of this project—what first drew you to this place in Cambodia?

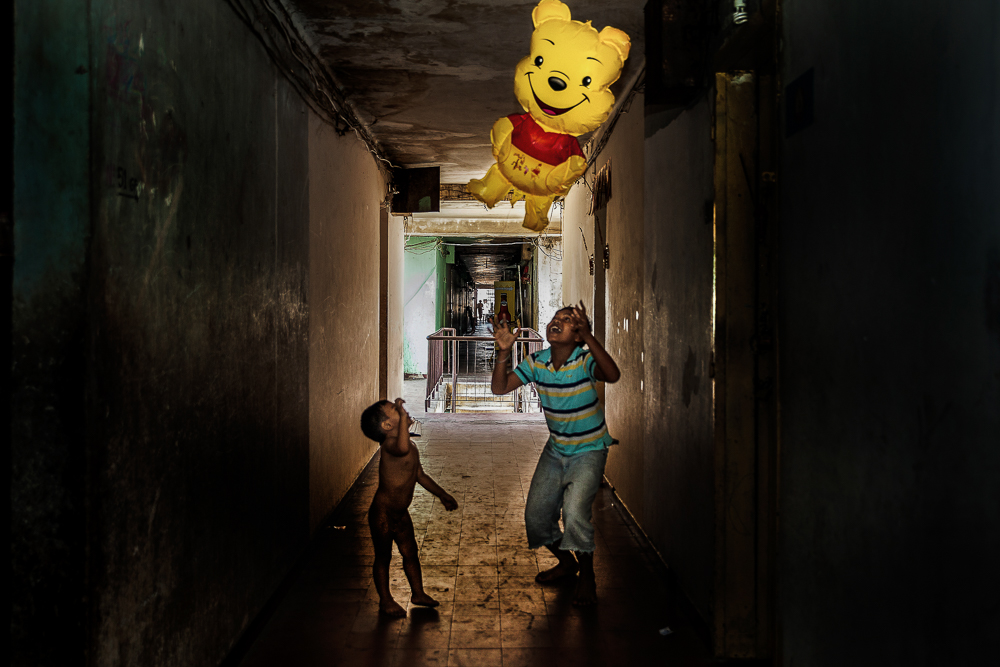

TZ: I was drawn to Phnom Penh’s White Building by the extraordinary resilience, creativity, and dignity of its residents. Despite poverty, stigma, and the looming threat of demolition, the community was vibrant and self-sustaining. On the surface, the building had a reputation as a hub of crime, but what I found was a neighborhood of families living in harmony.

My guides—students who lived there—were instrumental. They provided translation, access, and introductions, helping me connect with people I never could have reached otherwise. That experience taught me how vital a fixer is: not just for logistics, but for building trust and opening doors.

Q: How long did it take for the people around you to get comfortable with the presence of your camera?

TZ: Not long, and that was entirely due to my guides. Because they lived in the White Building, they were trusted. Their introductions meant people welcomed me into their homes. That early lesson—that a fixer is key to connection—has stayed with me throughout my career.

Q: What were you hoping to accomplish in documenting the space and community of The White Building?

TZ: My goal was to reveal authentic human stories. I wasn’t interested in documenting poverty as an object of pity. Instead, I wanted to show the spirit, strength, and beauty of lives lived under difficult circumstances. Having lived in ten countries and traveled to more than 150, I bring a multicultural lens to my work. For me, dignity and resilience are always central.

Q: Do you feel you achieved those goals?

TZ: Yes, though I sometimes wish I had immersed myself even more—perhaps by living in the building. Still, as one of my first major projects, it laid the foundation for everything that followed.

©Tariq Zaidi, Basile, 51, has been a sapeur for 30 years and works as a manager of human resources. His most treasured item of clothing is his Jean Courcel suit. Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo.

Q: Is there a common thread between The White Building and your more recent portraits from the Republic of Congo?

TZ: Definitely. For the past decade, I’ve focused on communities the world tends to overlook—from Brazil’s favelas to Haiti’s slums to Cambodia’s settlements. My aim has always been to balance depictions of hardship with the dignity and creativity people carry. My book Sapeurs: Ladies and Gentlemen of the Congo grew out of that same impulse: to show resilience and individuality in the face of challenge.

©Tariq Zaidi, Maxim, 43, has been a sapeur since he was seven years old. He mixes labels such as Yves Saint Laurent, Pierre Cardin and Christian Dior with suits that he has designed and made himself. Now married with two children, he teaches others the art of how to dress elegantly. Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo.

Q: The Congo portraits stand out for their staging—the use of branded clothing and the polished appearance of your subjects, often juxtaposed against rougher urban backdrops. How deliberate was your process?

TZ: Very deliberate. Sapologie is a culture of style and flair that dates back to the 1920s. The Sapeurs are taxi drivers, gardeners, tailors—ordinary working people—who transform themselves into icons of elegance after work. True Sapologie isn’t about expensive labels, but about the artistry of putting together a unique look that expresses one’s personality.

©Tariq Zaidi, Adzo, 46, is married with 10 children and owns a small clothes shop. He has been a sapeur for a decade. Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo.

Q: Were you aiming to challenge expectations in this work?

TZ: Exactly. Too often, marginalized communities are portrayed only through struggle. By showing the Sapeurs in their elegance, I wanted to flip that narrative—to highlight pride, joy, and cultural richness alongside the reality of their circumstances.

Q: Between The White Building and your Congo portraits, which body of work has been more gratifying for you?

TZ: The White Building lasted about 20 days, while the Sapeurs project stretched over three years. That depth made all the difference. What I’ve learned is that my personal preference is for long-term projects. They allow for richer storytelling and deeper understanding. Sapeurs became my first published book, confirming the value of slow, sustained work.

Q: Do you consider yourself a journalist, a humanitarian photographer, or a fine art photographer?

TZ: I see myself primarily as a documentary photographer with a humanitarian focus. My work often overlaps with journalism and fine art, but at its core it’s about exploring social issues, inequalities, and cultures overlooked by mainstream narratives. Respectful, long-term engagement has proven to be the most powerful way to make images that endure.

Q:Did being recognized as a Critical Mass Top 50 artist create opportunities for you?

TZ: The greatest benefit was the feedback from jurors. Their insights on sequencing, editing, and storytelling were invaluable. They helped me understand not just which images worked, but why—and how to arrange them into stronger narratives. The recognition also brought visibility, but the real prize was those lessons, which shaped every project I’ve done since.

©Tariq Zaidi, Yamea, 58, who has been a sapeur for half a century, brings colour and joie de vivre to his community. He has nine children and works as a brick-layer. His favourite item of clothing is his hat. Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo.

Astrid Reischwitz 2016

In her work, Astrid Reischwitz weaves together photography, memory, and handcraft to explore the fragile threads that connect family, culture, and time. Growing up in a farmhouse in northern Germany, she became attuned to the objects, stories, and traditions that shaped her heritage. Through series such as Stories from the Kitchen Table, Spin Club Tapestry, and The Taste of Memory, Reischwitz blends photographs with embroidery, recipes, and domestic artifacts, transforming them into vessels of remembrance. Her practice moves between preservation and reinvention, asking how memory functions, what is lost, and what endures. Recognized as a Critical Mass Top 50 artist in 2016, she has continued to build a body of work that is both deeply personal and universally resonant.

Astrid Reischwitz is a lens-based artist whose work explores storytelling from a personal perspective. Using keepsakes from family life, old photographs, and storytelling strategies, she builds a visual world of memory, identity, place, and home.

Her current focus is the exploration of personal and collective memory influenced by her upbringing in Germany.

Reischwitz has exhibited at national and international museums and galleries including the Florida Museum of Photographic Arts, Newport Art Museum, Griffin Museum of Photography, Danforth Art Museum, Photographic Resource Center, The Center for Fine Art Photography (CO), Rhode Island Center for Photographic Arts, Center for Photographic Art (CA), FotoNostrum, BBA Gallery, Dina Mitrani Gallery and Gallery Kayafas.

She has received multiple awards, including the 2020 Griffin Award at the Griffin Museum of Photography and the Multimedia Award at the 2020 San Francisco Bay International Photo Awards. Her series

“Spin Club Tapestry” was selected as a Juror’s Pick at the 2021 LensCulture Art Photography Awards and is the Series Winner at the 2021 Siena International Photo Awards. She is a four-time Photolucida Critical Mass Top 50 photographer and is a Mass Cultural Council 2021 Artist Fellowship Finalist in Photography.

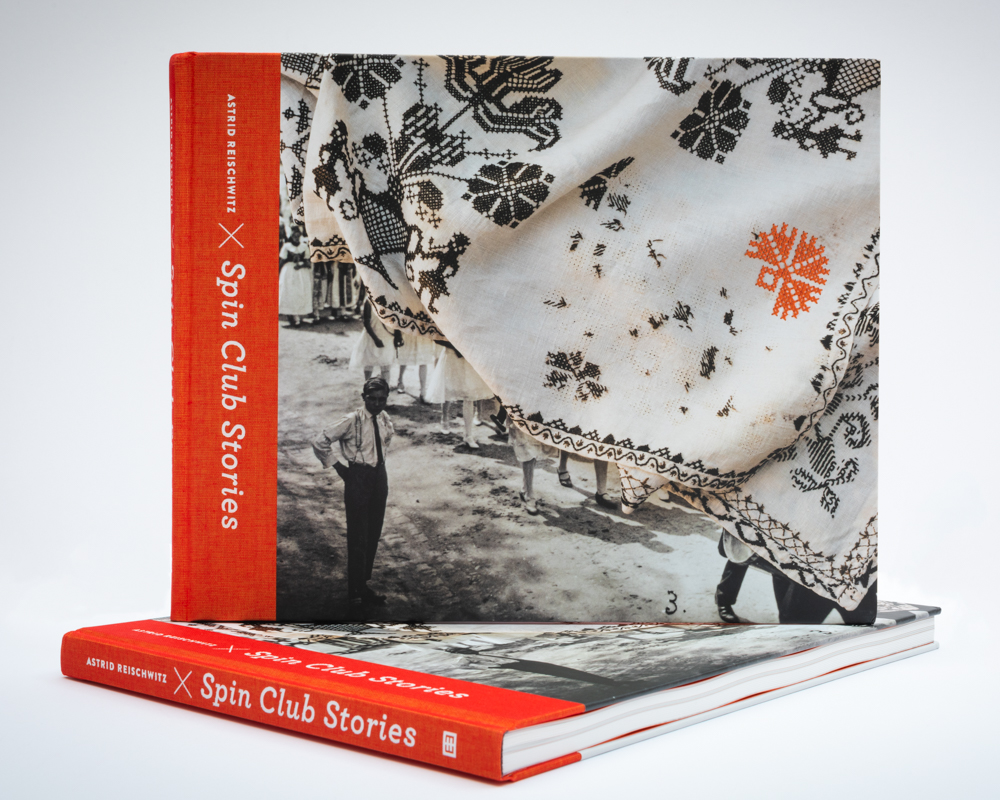

Her first monograph Spin Club Stories was published by Kehrer Verlag in 2022. It was shortlisted for the 2022 Lucie Photo Book Prize and received Silver placement at the 2022 Budapest International Foto Awards.

Reischwitz is a graduate of the Technical University Braunschweig, Germany, with a PhD in Chemistry. After moving to the US, she fell in love with photography and began her journey to explore life through creating art.

Q: How did you first learn about Photolucida’s Critical Mass, and what inspired you to submit your work to the competition?

AR: I first learned about Critical Mass while taking a portfolio-building class called Photography Atelier at the Griffin Museum of Photography. The program celebrates storytelling within a body of images and provides photographers the invaluable opportunity to have their work reviewed by more than 150 international professionals. What stood out most were the jurors’ personal comments, which became an essential tool for evaluating and strengthening my work.

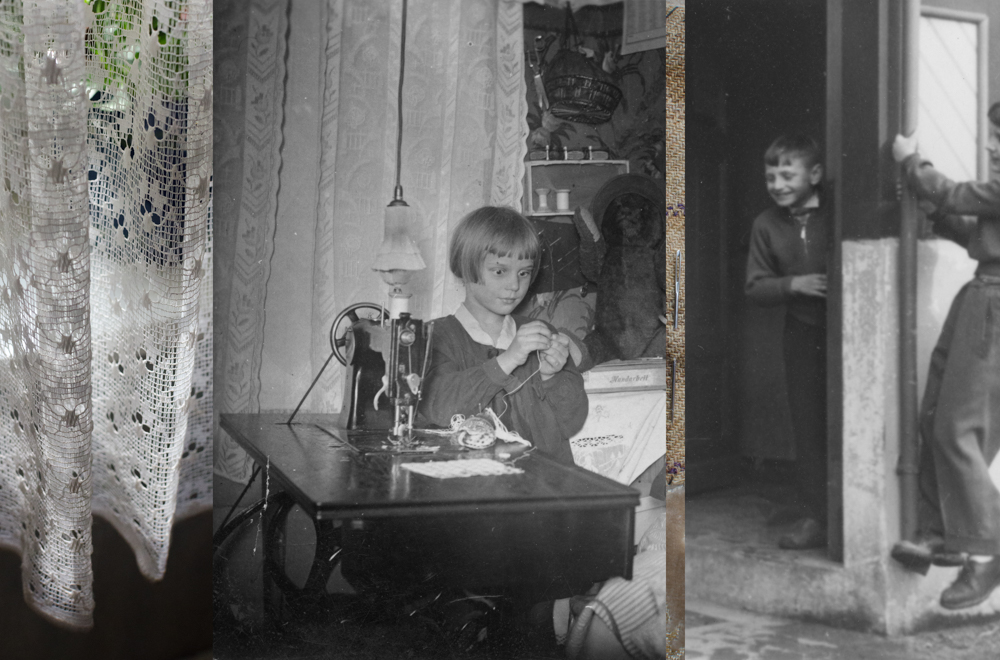

Q: Your 2016 Critical Mass Top 50 portfolio, Stories from the Kitchen Table, later expanded into your book Spin Club Stories published by Kehrer Verlag in 2022. Can you share the origins of this project and what first sparked the idea?

AR: I created Stories from the Kitchen Table to preserve and honor a fading way of life in my childhood home—our family’s farmhouse in northern Germany. The house feels untouched by modern time and, one day soon, will be left behind.

In the composite images, present and past stand side by side, often linked through fragments of vintage fabric. I came to see embroidery as a way to “stitch” together time—binding memory and tradition into a bridge toward the future. For centuries, women used embroidery as both self-expression and a form of communication, and learning this symbolic language was part of their legacy.

This realization inspired Spin Club Tapestry, in which I incorporated hand-sewn embroidery directly into my photographs. That act became a way to visualize cultural memory and to question how memory itself functions. The stitching both honors tradition and challenges the limits of recollection, connecting me more deeply to my heritage.

Both portfolios are intrinsically linked, making it natural to bring them together in Spin Club Stories.

Q: Family memory and storytelling are at the heart of this series. How did the kitchen table become, for you, both a symbolic and literal place for passing down traditions?

AR: The kitchen table is quite literally where traditions are passed down—through stories, celebrations, and food, which holds its own power of memory. Photographs, too, function as memory triggers. The composite images in Stories from the Kitchen Table are my way of symbolically passing these traditions forward to the next generation.

Q: You often merge photography with embroidery and other handwork. How do these tactile interventions alter the meaning of the photograph, and what do they contribute to the larger narrative of memory?

AR: Following the stitches in traditional fabrics is like following a path through my ancestors’ lives—their patterns, their mistakes, their artistry. The stitches I add into my photographs are abstractions, fragments of those originals. They suggest that memory, too, is incomplete—shifting and changing every time we revisit it.

By leaving some stitching unfinished, I invite the viewer to continue the path themselves, to create new meaning. In this way, embroidery becomes a language of both preservation and loss, communicating what risks fading from cultural memory.

Q: The series reflects on memory, loss, and cultural heritage. What do you hope viewers—especially those outside your own cultural background—take away from these intimate family stories?

AR: My images are an invitation to reflect on one’s own cultural inheritance—how it shapes us, what we can learn from it, and how we can use it to create our own unique paths. Even if the details are different, the themes of memory, tradition, and loss are universal.

Q: In your more recent series, The Taste of Memory, the compositions echo Dutch still-life painting while drawing directly from your family’s kitchen traditions. How does this blending of art history and personal memory shape the visual language of the work?

AR: The visual language of The Taste of Memory emerged as I worked with old family recipes from the farmhouse. I wanted to represent the rhythms of village life in northern Germany as I knew them. The darkness surrounding the artifacts reminded me of the atmosphere inside those old farmhouses, while also echoing Dutch still-life paintings. That timeless quality allows the images to transport us emotionally into another era.

Q: You’ve described recipes in this project as “stained with use and memory.” How do these timeworn artifacts serve both as evidence of daily life and as symbols of an evolving cultural identity?

AR: Many of the artifacts I photograph were found in the farmhouse—objects once used in daily life by generations before me. To me, the house is like an uncatalogued museum. Sometimes I don’t even know what a tool was originally used for, but its presence tells a story of lives lived. These objects remind us how cultural identity shifts over time, carrying both continuity and change.

Q: Some works incorporate embroidery fragments and domestic objects once tied to life events in your village. How do these materials transform the photographs into vessels of remembrance and cultural preservation?

AR: Recipes and textiles are gateways into memory. Embroidery fragments—once used on dish towels to mark weddings, births, or funerals—now speak to both celebration and loss. Likewise, domestic objects, once central to daily rituals, would disappear if not preserved in these images. By incorporating these materials, the photographs become vessels of remembrance, carrying fragments of culture forward.

Q: This series feels like both a farewell to your family farmhouse and an opening toward new stories. How do you imagine viewers connecting their own experiences of food, tradition, and memory to your images?

AR: The Taste of Memory is indeed a farewell, as I will soon say goodbye to the house. But I believe many viewers will recognize their own stories here—whether it’s a grandmother’s kitchen, a family recipe, or a holiday table. Food, like photographs, anchors memory, and it shapes who we become.

Q: Looking back, how did being recognized as a Critical Mass Top 50 artist shape your career, and what kinds of opportunities or connections have emerged from that recognition over time?

AR: Being named a Critical Mass Top 50 artist was a milestone. It affirmed that my work resonated beyond my immediate community and gave me the confidence to continue exploring themes of memory and heritage. It also opened doors to new connections—with fellow artists, curators, and jurors—relationships that continue to sustain and inspire me. Exhibiting these works allows the memories they carry to live on and evolve in conversation with new audiences.

Photolucida is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Our mission is to provide platforms that expand, inspire, educate, and connect the regional, national, and international photography community.

Instagram: @photolucida

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)October 1st, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: George Nobechi (2021) and Ingrid Weyland (2022)September 30th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Amy Friend (2019) and Andrew Feiler (2020)September 29th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Jennifer McClure (2017) and JP Terlizzi (2018)September 28th, 2025