Elaine O’Neil and Julia Hess: Mother Daughter, Posing as Ourselves

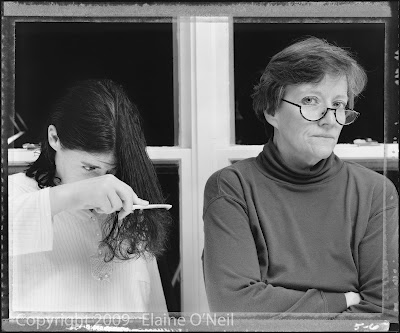

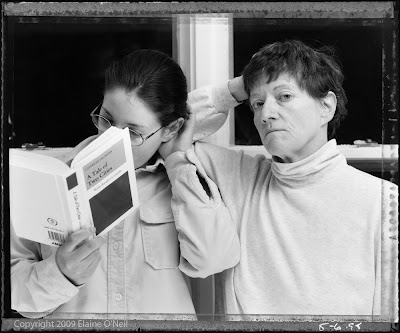

Documenting our lives is a complex task. We bring our own perspectives to family dynamics and often times the participants are presented in ways that are not completely authentic. This is not the case with photographer Elaine O’Neil, who made the brave committment to photograph herself and her daughter Julia, every day for five years, using a 4×5 camera and the living room window. The project: Mother Daughter: Posing as Ourselves is now a monograph and an exhibition, currently on view at the Griffin Museum’s Stoneham Atelier Gallery running through May 20th. This project has been featured at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, at Haverford College in Haverford, PA, at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia, and at the School of Visual Arts and Sciences Gallery at the Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, NY.

The production of her book has an interesting history: ” I submitted our book proposal about the time [Cary] Press Director, David Pankow, was developing a research project centering on the challenges surrounding the accurate reproduction of fine art, silver halide black and white photographs. What I perhaps didn’t state clearly enough is that this project concerned the challenges of making digital replicas, or facsimiles of photographs. During testing and printing, the digital reproduction of every image in the book was measured against the highest quality silver print that I could make. When a print from the book and a silver print, matted to hide the substrate, are set side by side – no one has been able to tell which is which.

This processes is unique to this book. It was determined that it is impracticable, if not impossible to use it as a consumer printing process. The book can be ordered from Amazon or from the publisher, Cary Graphic Arts Press.”

Elaine has exhibited widely and her work can be found in many public and private collections. She also is a noted educator who has lectured and taught in Brazil, England, Israel, Australia, and throughout the United States. She currently teachers graduate fine art at the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York.

Mother/Daughter: Posing as Ourselves: In preparation for the phase of life my ten year old daughter, Julia was about to enter, I began to read about the experience of adolescent girls in our culture. In the work of Carol Gilligan and other researchers at Wellesley College’s Stone Center, I found the clearest description of the compelling, unmentioned issues of adolescence—loss of voice, loss of identity and loss of connection.

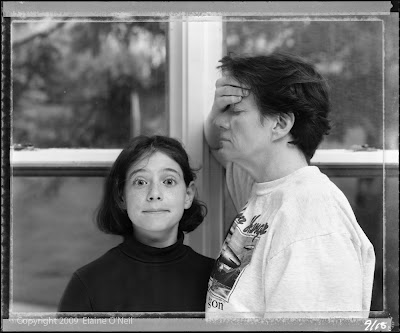

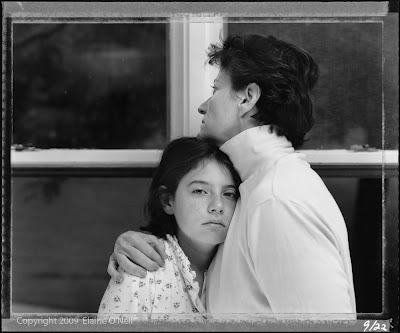

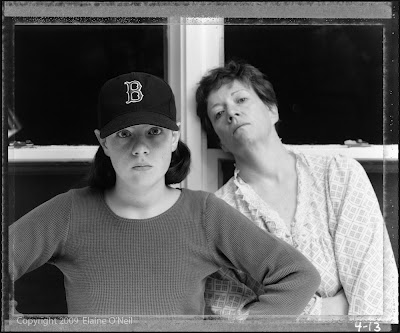

My counter to culture’s effect on Julia’s self-esteem was to create a project which would allow Julia to present herself as truthfully as she wished, while fostering our sense of connection. I suggested, and Julia agreed that for one year we would meet for a few minutes every day in front of the honoring presence of the camera to make a portrait of ourselves. One end of the living room was converted into our studio, with the windows overlooking the backyard garden serving as our the backdrop. The windows were chosen for their graphic pattern, and a middle sash which would serve as a gauge of Julia’s growth. More important was the reference to a specific landscape allowing nature to serve as a metaphor for the impending change in our relationship and in my definition of mother.

Ultimately we met in front of that window for five years, until Julia decided that her 16th birthday was the day upon which the project would end. We rarely discussed how we would pose, choosing to remain independent by relating to the camera. The result is 1,800 photographs in which as Susan Stoops, then curator at the Rose Museum at Brandeis stated, “Julia participated fully, demanding her space and the maintenance of autonomy in order to present herself as she wished.” What is also revealed is my need to reassert my autonomy and to reclaim an identity outside of the persona of mother.

INTERVIEW with Elaine (Mother)

What were the best and worst parts of creating this project?

I really can’t think of a worst part. I was shocked the day I processed the picture we took on April 13, 1996. When I peeled the Polaroid negative and print apart I saw a picture of my relationship with my mother rather than the one (I thought) I had with my daughter. We rarely discussed anything before we took a picture and I couldn’t remember then, and don’t remember now, what was going on that day or how we got into the pose. But we all think we are so different from our mothers and it is always a shock when one is reminded of how much we are like them.

Second, I was a bit worried when at 15 Julia said she would only pose one more year. By then I couldn’t imagine how life would be when one was not making a picture every day, and wondered how it would alter our relationship. As it turned out, 16 was the perfect age to stop because it is really the age when Julia became engaged with her world beyond the family.

The best part is that it fulfilled one of the original intentions for doing the project. It created a point in every day during which, no matter what else was going on, we did something together which was unique to our relationship.

Did this working relationship create a deeper personal relationship between you both?

I don’t know if it created a deeper relationship, but it maintained the relationship we had developed in Julia’s first 12 years while we both were changing.

A second reason I proposed to the project to Julia was my reading about the changes imposed upon girls between the ages of 10 and 13. It is during that stage that they learn to distrust themselves and to deny who they truly are.

In my research I learned that for girls it is a continued relationship with their mother which is crucial to becoming self-actuated women. I was working 60 hours a week, she had her life, and we could have been proverbial ships passing in the night if we didn’t make time to reinforce our relationship.

Have there been any insights that you have realized after the work was created?

The first is understanding that both of us were committed to being as honest as we could in front of the camera. At one point while editing for the book, I got about half way through the images we had chosen and I stopped cold wondering how we ever did this. Until that moment I did not know how powerful a body of work Posing As Ourselves is or how much we had both been willing to reveal. At times I am still amazed by it.

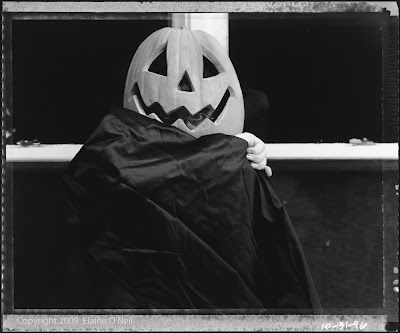

The second is perhaps a reaffirmation of the truth that relationships are sustained by the little things, the daily rituals, the moments forgotten as soon as they happen. When I look at the work now, I understand Julia and I in a completely different way that I would have if I had only pictures of the cultural rituals of Birthdays, Christmas, Halloween and Easter. I don’t think I can explain it any more clearly – all I can say is that it is that I am so happy that we did it and how we did it.

There have been two surprises:

Everyone who sees the work wants to discuss their family – the woman at the copy shop, that man installing the air conditioning, my students, peers, my Representative to Congress.

The work is not gendered. Men and women want to talk about their relationships with their children, or their parents, or their siblings.

INTERVIEW with Julia (Daughter)

What were the best and worst parts of creating this project?

In terms of the actual work that was required to complete this project, I have to give all of the credit to my mom and dad. While the project was happening I feel like I was allowed to flit in and out of the picture whenever we decided to take it on a given day. Which was maybe a good thing in that it somewhat reinforces the idea that we were able to come to the picture free to express whatever emotion we were feeling at that moment. But once that moment was done it was my mom that took on the task of organizing and storing the photos, developing, my dad did a lot of the printing. In putting the book together it was again my parents that did so much of the legwork, although I was definitely part of the collaboration when it came to which pictures my mom and I wanted to include.

So I can’t really think of a worst part. There were days that I remember I did not feel like having my picture taken, and I think that comes through in my body language or expression. But as corny as it may be, without those bad days included the truth to the work, the “relateability” to the project would be lost.

The best part of the project I think is having those pictures to go back and look at. Although I can still remember the context for so many of them, what I was doing, why I posed that way, how I was feeling, and thus still have a memory associated with the project, there is still something about having a tangible object to look at that I like, and that adds something. Maybe it is as I discuss in the Epilogue of the book, that my memories of that time spent with my mother are those of an 11 to 16 year old, and as a result are totally concerned with myself. Having the documentation of the memories allows me to see not only myself but my mom as well, what she was doing, how she was feeling.

Did this working relationship create a deeper personal relationship between you both?

Yes, although I know I did not realize it at the time. And even now I don’t know that I could articulate how it brought us closer or give examples. But speaking from the mindset of a teenage girl, it helped that I had a really great group of friends in high school that were really supportive of the project. They all thought it was very cool that I had parents who were photographers, and many of them have had their pictures taken with that camera. So I think that made it easy for me to readily accept the project as a part of my life, and a good part of my life at that.

Having worked on the book with my mom, and having participated together in the speaking engagements, openings and shows that the book has afforded us, we have been able to start a new phase of our relationship to one another as two adult collaborators. Although I have been an adult for a while now, my relationship to my mom is and has been one of a mother and her adult child. It has been a real opportunity to be in a situation where my mom and I see each other in a different way, and as a result are able to view and interpret the work in a different light.

Have there been any insights that you have realized after the work was created?

I think the two insights that I have had echo some of the statements that I have mentioned in the other two questions. First, one of the big realizations that I have as I look back at the work is that my relationship to the work has changed with my changes in age. While the project was going on, my first thought and concern when looking at the work was with myself. My eye was immediately drawn there, as I think any teenager’s would be with their own image. As I said in my artist’s statement, which I wrote about six months before the project ended (and I cringe as I go over the words of my 15 year old self) “I could say that this project is a meaningful part of the my life, but it isn’t. Maybe when I’m 30 it will mean more to me than it does now.” As a 15 year old I know that I thought 30 was an eternity away. Now, this year I’ll be turning 30 and my reactions to the images are very different. I think I am able to see the images as a whole – seeing not only myself, but my mom, the window, what is outside of the window. And I think my relationship with the work will keep changing as I get older and hopefully start to have children of my own.

Second, is that not only is my relationship to the work changing with time, but my relationship to my mom has changed as we have been working together on this project as collaborators and co-authors. I think that was an unforeseen consequence of the project on my and my mom’s part, but it has turned out to be an opportunity that I don’t think we would have ever gotten otherwise.

Thank you to Elaine and Julia for their sharing their personal insights.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026