The CENTER Awards: Project Development Winner: Adam Reynolds

For the next two weeks, Lenscratch will be celebrating the 2014 CENTER Award Winners. We are thrilled to align with such a wonderful organization that honors, supports, and provides opportunities to gifted and committed photographers. For 20 years, CENTER has launched careers, provided incredible exposure and inspired photographers to create work that excites and challenges the photographic dialogue.

Today we celebrate Adam Reynolds‘ Project Development Award, starting with juror, Lisa Hostetler’s, statement.

PROJECT DEVELOPMENT: Juror’s Statement

JUROR LISA HOSTETLER, Curator-in-Charge, George Eastman House

It has become a juror-statement cliché to say things like this, but that doesn’t make it any less true: choosing a winner from among the bevy of deserving projects submitted this year was a daunting and difficult task.

Because this is a project development grant, I knew that the work I was seeing was not necessarily in its final form and that evaluating the potential of an idea based on the evidence of its current visual and conceptual shape can be a delicate operation. Nevertheless, it is also exciting—and a distinct privilege—to meet an artwork in its youth and speculate on what it might become.

With photographic series, the results are particularly unpredictable and (ideally) rewarding because each new image maps a different intersection of photographer and world that often changes the dynamic of the body of work as a whole. So I looked for work that seemed to have a firm intellectual basis, a solid direction for growth, and a strong visual sensibility. This helped me to reduce several hundred submissions down but then getting to a short list of finalists was a challenge; deciding on the winner was fairly excruciating.

In the end, I chose a project that was entirely new to me and that seemed particularly timely. Adam Reynolds’s Architecture of an Existential Threat depicts rooms in the Middle East that double as ordinary, workaday places and as bomb or air-raid shelters. The pictures’ solid formal structure and uncanny emptiness, combined with occasional residue of their utilitarian function, lends an air of foreboding to the images. They not only visualize the contradiction of “ordinary” life in dangerously unpredictable circumstances, but also heighten our awareness of the subtle ways in which physical space becomes charged with meaning. I look forward to seeing how the project develops.

I want to thank all of the photographers for sharing their work with me. There was a lot of strong photography here, and I’m grateful for the insights that each new project offered. Good art refreshes one’s perspective on the world; I was lucky enough to have my mind recalibrated many times during this process.–Lisa Hostetler, Curator-in-Charge, George Eastman House

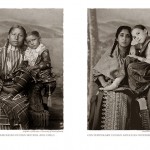

Adam Reynolds’ Artist Statement: Architecture of an Existential Threat

Since its creation in 1948, the State of Israel has felt itself isolated and beset by enemies seeking its destruction. I feel that this collective siege mentality is best expressed in the ubiquitousness of the thousands of bomb shelters found throughout the country. By law all Israelis are required to have access to a bomb shelter and rooms that can be sealed off in case of an unconventional weapons attack.

The shelters come in all shapes and sizes. Along with the more conventional below ground bomb shelters, there are underground parking garages that can be converted into a nuclear-proof bunkers and hospitals able to accommodate thousands, entire schools encased in reinforced concrete with blast-proof windows, and small, one room “mamads” in private residences meant to withstand rockets and unconventional weapons attack. It is not unusual to re-purpose bomb shelters for broader uses, such as dance studios, community centers, pubs, mosques, and synagogues.

These shelters are the architecture of an existential threat – both real and perceived. In them can be seen Israel’s resiliency as a nation, and its inability to come to terms with itself and with its neighbors in a volatile region. The resulting images offer a window into the collective mindset of the Israeli people, how they have normalized this “doomsday space” into their daily lives.

Adam Reynolds is a documentary photographer whose work focuses primarily on the Middle East. He began his career covering the region in 2007. Adam holds undergraduate degrees in journalism and political science from Indiana University with a focus in photojournalism and Middle Eastern politics. He also holds a Masters degree in Islamic and Middle East Studies. Currently Adam is an MFA candidate in fine art photography at Indiana University in Bloomington.

His work has appeared in: Smithsonian Magazine, The Guardian, Bloomberg News, The Indianapolis Star, The Washington Times, The Associated Press, Nox Magazine, The Times of London, The National, the Christian Science Monitor, The Australian, The Globe and Mail, and The Boston Globe among others. Adam is a frequent contributor to Corbis Images.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Yorgos Efthymiadis: The James and Audrey Foster Prize 2025 WinnerJanuary 2nd, 2026

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)October 1st, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: George Nobechi (2021) and Ingrid Weyland (2022)September 30th, 2025