Review Santa Fe: Julie McCarthy: The Last Great War/Postscript

Julie McCarthy brought a personal body of work to Review Santa Fe. Her series, The Last Great War, started out as documentation of a war her father was fighting against time and good health, but evolved into a deeper understanding of a parent through his history and artifacts. Hers is a universal story wherein our investigations come too late and our revelations are after the fact, but comfort us in the next phase of loss and memory.

Julie McCarthy brought a personal body of work to Review Santa Fe. Her series, The Last Great War, started out as documentation of a war her father was fighting against time and good health, but evolved into a deeper understanding of a parent through his history and artifacts. Hers is a universal story wherein our investigations come too late and our revelations are after the fact, but comfort us in the next phase of loss and memory.

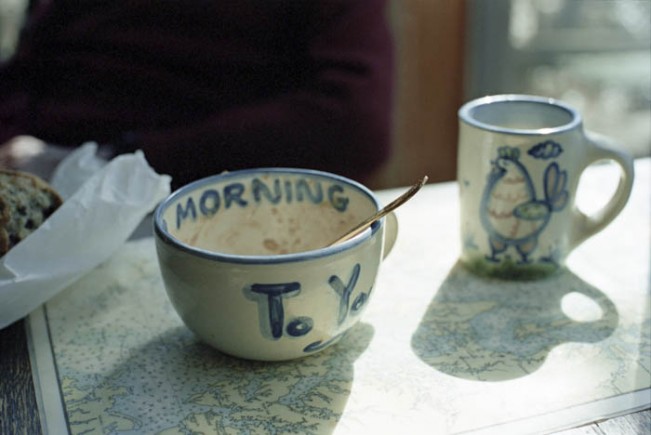

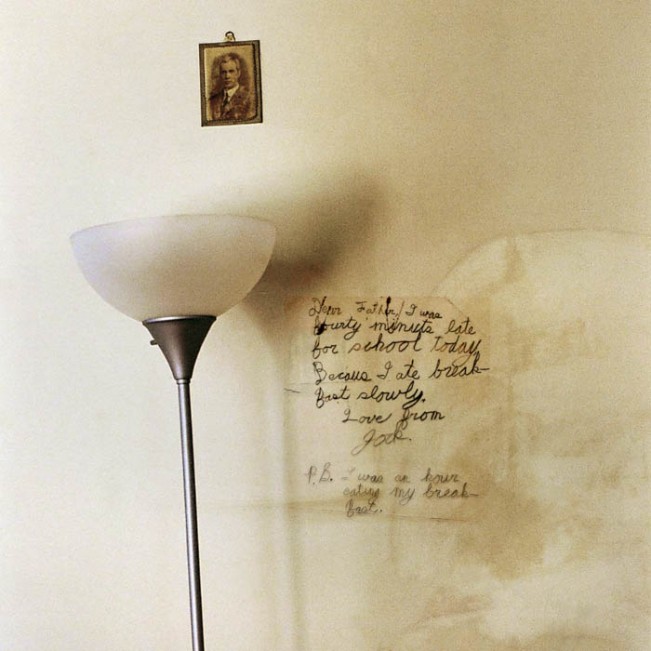

Julie comes from a family of storytellers and her work has a narrative thread that runs through it. Some narratives are literal and can include text and others are more poetic inviting the viewer to create their own story. She is drawn to themes that are a part of our daily lives and culture such as a sense of home, belonging and the way the past informs the present. She is also a street photographer delighting in the endless ways human beings can make you laugh or break your heart in a single gesture.

Julie’s work has been widely exhibited throughout New England. She received the Juror’s Recognition Reward from the Monmouth Museum, Monmouth New Jersey and has had a one person exhibition at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, MA. Her work has appeared in Shots Magazine, The Sun and many others. She has published a book The Hair Project, that includes portraits of women who have lost their hair to chemotherapy with accompanying text written by each woman.

Julie lives in Stockbridge, MA with her family

My father represented the end of an era. He fought in World War II, “the last great war”, and he lived by a code of ethics that included a sense of honor, a fierce independence and a rugged individuality. He was also stubborn, opinionated and kept his emotions tightly reined in. Our relationship was not easy. I was the oil to his vinegar.

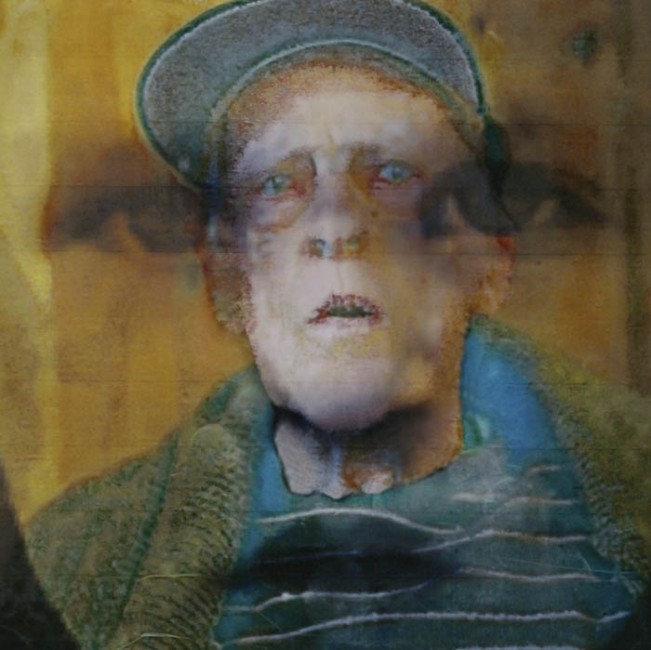

I began to photograph my father on his 94th birthday. As I continued, a portrait emerged of a man I knew but had never really noticed. His home and his possessions displayed a sense of beauty, whimsy and a strong sense of family, but the man himself was frail and vulnerable-no longer the looming presence of the past. The camera between us served not as a barrier, but as a bond. When he died four months after I started to photograph, I felt a sense of peace.

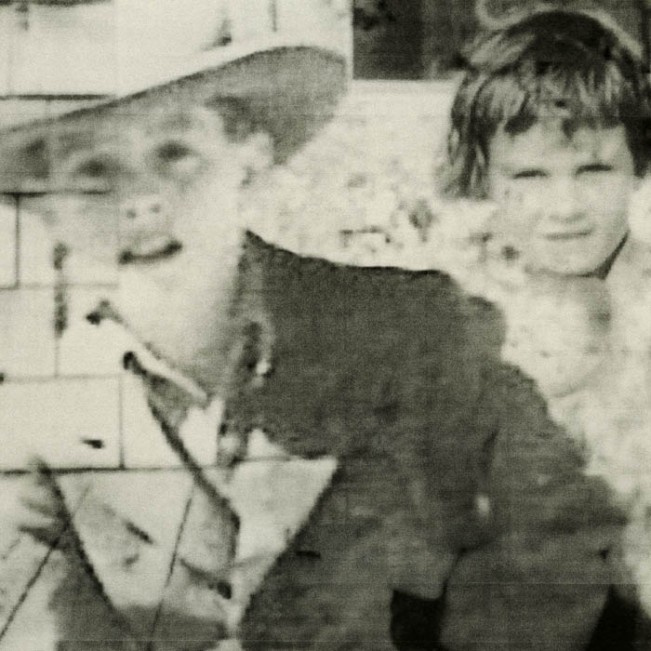

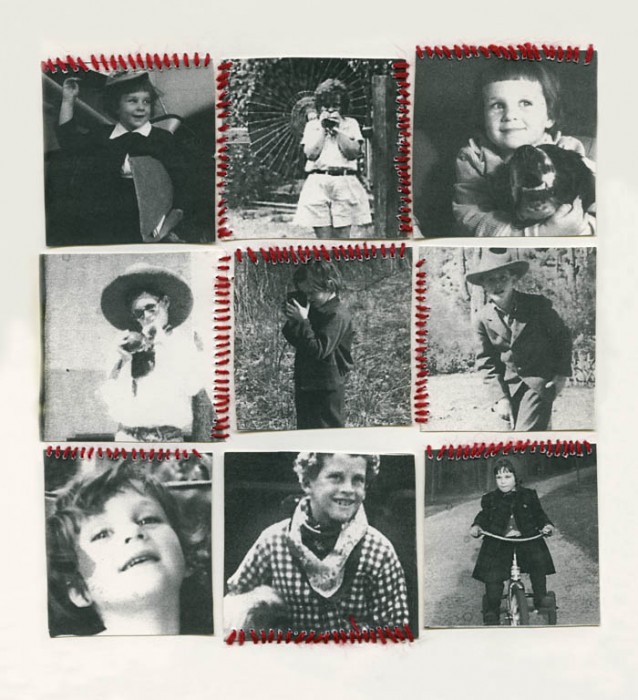

After my father died I decided that I wanted to have the conversation I always wanted to have with him-a give and take, gentle and loving. I found, nestled in boxes and desk drawers, photographs of him as a young boy, notes to his parents, drawings and all kinds of memorabilia. I also found pictures of myself as a young girl. A conversation began to emerge child to child. Using the tools of a child-scissors and glue-with his now empty house as a backdrop, I wove together, sometimes literally, the photographs. The similarities and differences are evident, but they sit side by side in a kind of harmony

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026