Ken Abbott: Useful Work: Photographs of Hickory Nut Gap Farm

Ken Abbott’s photography and Hickory Nut Gap Farm is a marriage made in heaven, or about as close as we get to heaven here in the Blue Ridge Mountains in western North Carolina. For almost a hundred years, one extended family has lived on and created a uniquely beautiful farm and community in this place. In Useful Work, Ken Abbott so thoroughly and beautifully depicts the surface and soul of this home and farm, that he reminds us how the best photographers can focus on something seemingly small, yet evoke our common humanity. This book represents an extraordinary achievement in life and in art.– Alex Harris, Center for Documentary Studies, Duke University

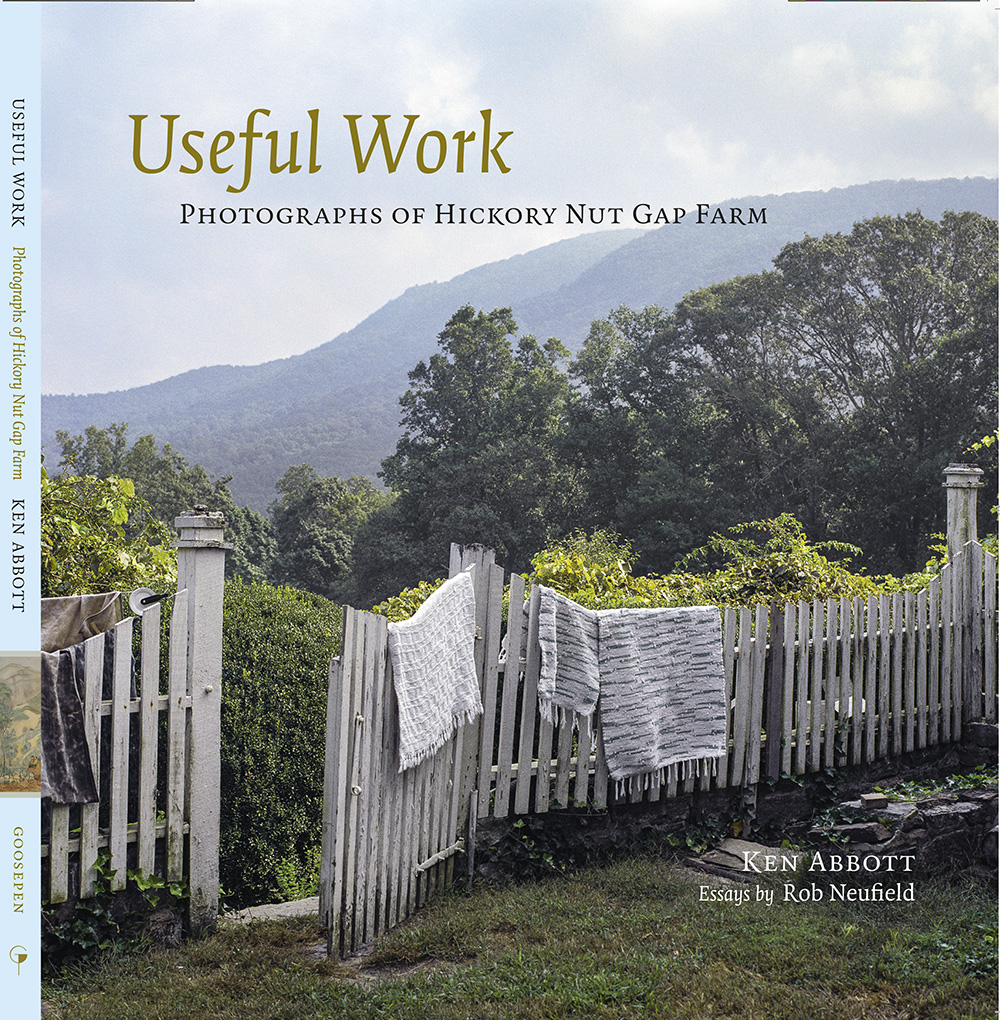

Photographer Ken Abbott has quietly and beautifully captured the Hickory Nut Gap Farm, “perched near the top of the Eastern Continental Divide, in Western North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains.” It’s a place that reflects over a century of American history, the owners maintaining a reverence to the land and the beauty it holds. Ken has created a book of this project, Useful Work: Photographs of the Hickory Nut Gap Farm, with essays by Rob Neufeld. Useful Work is being featured at the Turchin Center for the Visual Arts, at Appalachian State University, in Boone, NC through May 6, 2017, and at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke opening June 2, 2016.

Ken Abbott grew up along the front range of Colorado and received his MFA in photography from Yale University in 1987. He was the principal photographer for the University of Colorado at Boulder for fifteen years. He now lives with his family in Asheville, North Carolina, and received an NC Arts Council Fellowship Award for his photography at Hickory Nut Gap Farm in 2006. Useful Work: Photographs of Hickory Nut Gap Farm, was published in 2015 and is his first book.

Useful Work: Photographs of the Hickory Nut Gap Farm

In 2004, my daughter’s preschool class went on a field trip to Hickory Nut Gap Farm, a few miles outside of Asheville, in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Western North Carolina. Established in 1916 at what was formerly an inn and stage coach stop on one of the oldest roads from the southern Appalachians to markets on the coast, the farm became my regular destination over the next several years – a sumptuous and inspiring place with a history and community built around it that helped me dig deeper into what was at that time my new home.

I learned on that field trip that Jim and Elizabeth McClure had bought the old inn while on a honeymoon visit from Lake Forest, Illinois, and that Jim had founded there and administered during his life the Farmer’s Federation, and that their son in law, who’d passed away only a few years before our visit, had been a representative in the U.S. House. But the real hook for me was the beauty of the old inn and the gardens, which I learned I should credit to the family’s matriarch, Elizabeth, who had studied painting in Giverny, France, prior to WWI, and had once written in a letter to her cousin of how she and her classmates could walk into the fields adjacent to the school and watch as Claude Monet painted the haystacks.

Elizabeth had transformed the house and gardens, and I loved that her aesthetic was in evidence and cherished, but had not been fussily preserved by the family. Throughout the generations, the house had hosted the busy and thriving daily life of a family that was deeply enmeshed in the workings and engagements of the surrounding community, Fairview, as well as in the daily work of the farm, and the experience of those times showed, even glowed in the house, like the patina on a fine old bronze.

A friend recently wrote to me, “the subject of your book drew you in kind of gradually and made itself irresistible.” I will say that from the moment I first saw the house and farm, my work there seemed inevitable, and yet as my friend’s comment implies, I had some internal conflicts about it. Sometimes the photographs I made seemed almost too easy, and I worried that in some way my subject was just too beautiful. But eventually I learned to appreciate the abundance of the place for what it was, a gift, like the spring Elizabeth wrote of to her cousin in her early days at the house, “…the finest little spring you can imagine flowing so freely that it can be piped to the house by gravity….” Despite their ease and beauty, the pictures I was making at the house felt true and important to me. Elizabeth once wrote in a letter to Jim, “Everybody wants beauty––it seems always to quicken your sense of being alive and that means happiness and peace and a blessed conviction that you are really necessary in the scheme of things.”

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026