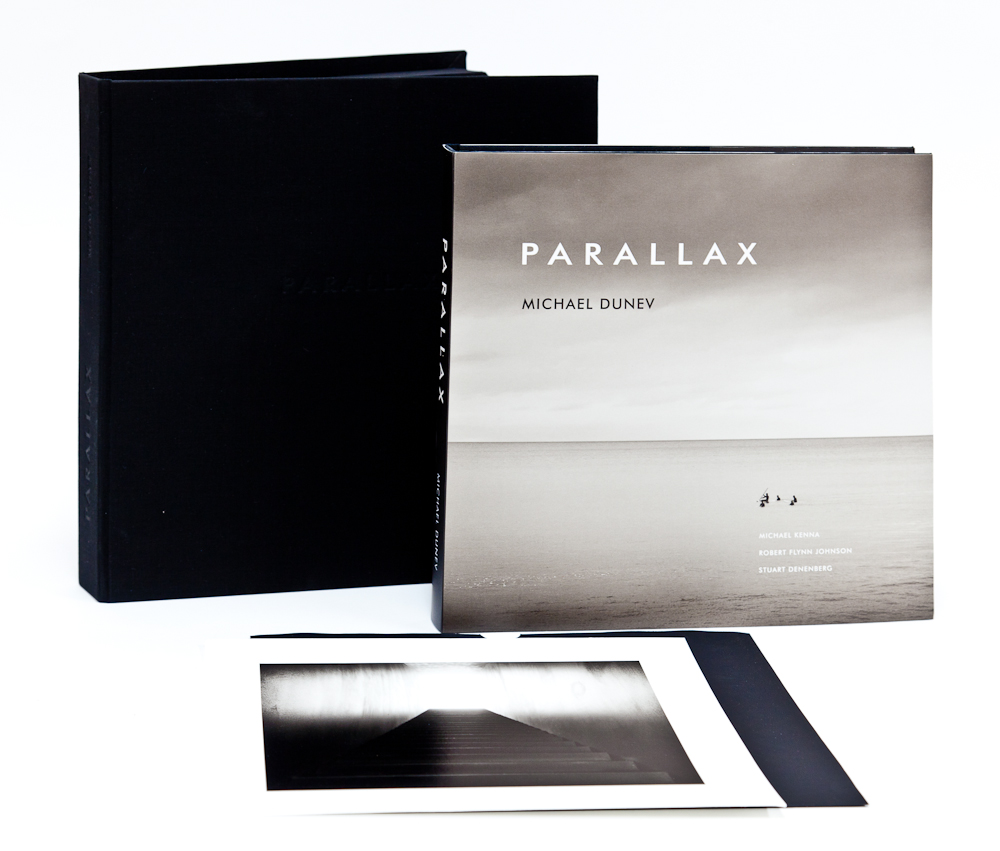

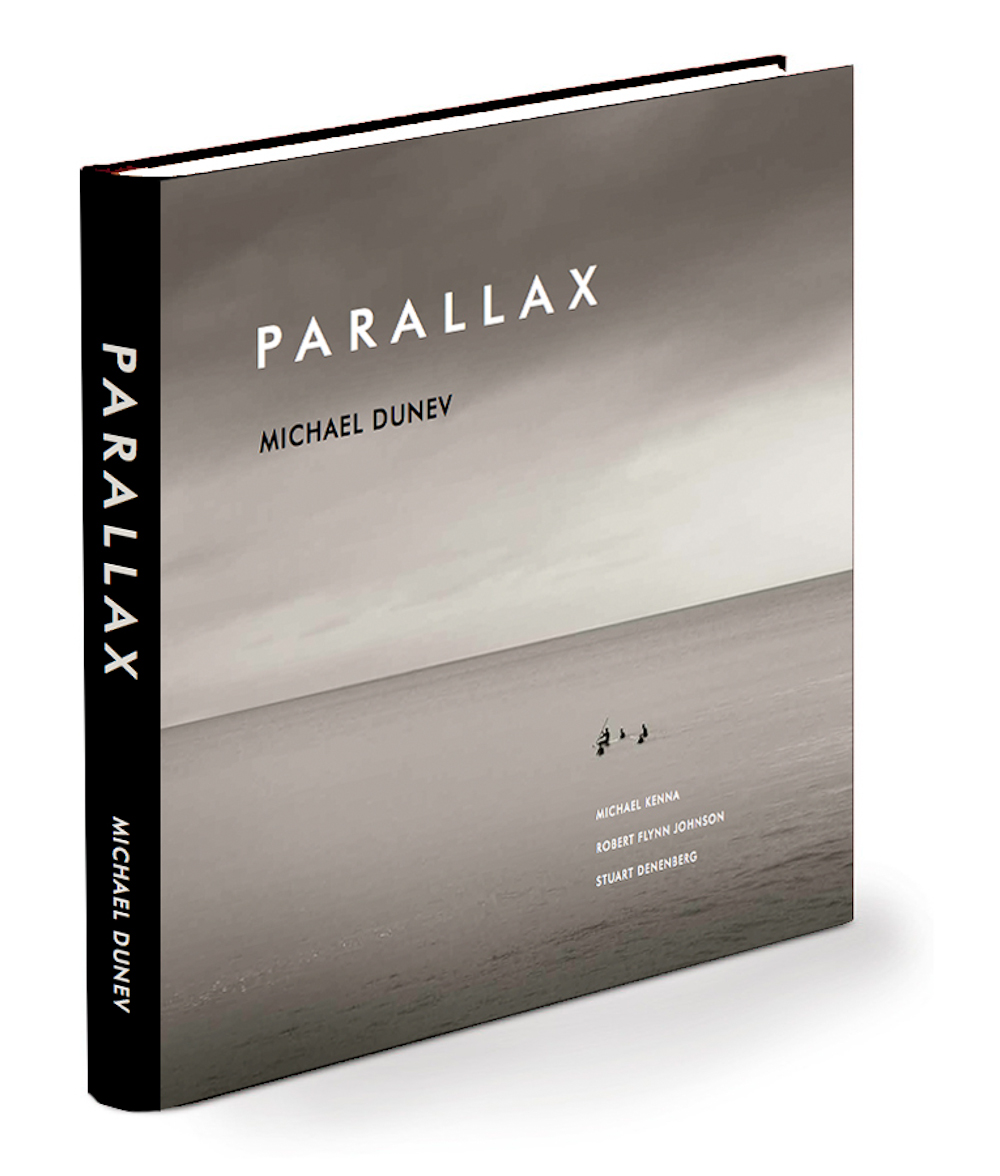

Michael Dunev: Parallax

Sometimes we get so caught up in the intention of photography or finding subjects to build a project on, that we forget the beauty of simply taking photographs. Michael Dunev has just released a significant monograph, Parallax, recently published by Poligrafa in Spain, showcasing 45 years of black and white stunning photography. Parallax offers an overview of images from time spent in Peru, Mexico, the United States and Europe and traces his personal development in photography since 1970. The book includes text by

Michael Dunev (Madrid, Spain, 1952) spent most of the seventies in South America, mainly in Peru and Brazil. In Rio de Janeiro he worked as a photojournalist, publishing his photographs in various Brazilian magazines. The eighties found him in the US, living in Vermont and California, where he combined his photographic work with theatrical lighting design and independent film projects.

A graduate of the San Francisco Art Institute, Dunev opened a contemporary art gallery in the same city in 1982, representing established and mid-career artists, an activity he has pursued to this day. In 1991 he founded an art press and became involved in the publishing of artists’ books and monotypes. Eight years later he sold the press and closed the San Francisco gallery to return to Spain, where he opened a contemporary art space in Catalonia.

An art gallery director, art publisher and photographer, Dunev has been loath to present his own work within the framework of his gallery, so many of his works have remained unseen to the general public. Recent gallery and museum exhibitions in Spain, however, have spurred an interest in his work as a photographer, resulting in the publication of Parallax, a monograph spanning over four decades of looking at the world.

Dunev’s images cover leitmotifs that have been of central interest to him during the last four decades, such as solitude, as manifested within the urban landscape, the intersection of man and nature, and the impact of mankind on the natural world. Drawing on his personal evolution in the field of photography since 1970, when he started using the camera as a means of visually registering and exploring the world, the subjects of these photographs were shot mainly in Europe, Peru, Mexico, and the US –places where the author has lived or repeatedly spent long periods.

As noted by Robert Flynn Johnson, Curator Emeritus of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, “The photographs of Michael Dunev exhibit a sophisticated understanding of modernist attention to structure, perspective and the dynamic framing of imagery. The fragments of experience his lens capture are, more often then not, spare and restrained with the moisture of extraneous detail wrung out. They elicit a de Chirico mood of retrospection in their elegant angled vacancies…. doors left open for our eyes and minds to enter and inhabit.”

On Parallax

We are told that a shift in the angle from which something is observed alters our perception of it and they call it parallax. In quantum mechanics, the physicist Werner Karl Heisenberg noted that the simple act of observing something alters its position and he called it the uncertainty principle.

The very nature of photography, that ability to capture a moment and revisit it later, at another time, allows us to peer into a window to the past and observe that moment frozen, like a fly trapped in amber. When reflex cameras are used, the instant of snapping the picture is unseen to us, as the shutter release raises the mirror, blocking our view of the object. It is only after it has been processed that we can see the photograph, and the results are often unexpected. With rangefinder cameras, like the old Leica used in many of these photographs, that instant is never concealed by the mechanism of the shot. Your mind’s eye registers the exact moment you choose to press the shutter and, in the processing that comes later, you seek affirmation in the film of that which you hoped to capture. Yet viewed from the distant perspective of time, the photograph takes on a quality of its own, you are no longer emotionally involved in its creation and a certain detachment occurs.

The photographs contained herein are a record of some things I have seen since I first began to use the camera as a framing tool in 1970. They are a subjective interpretation of topics that have concerned me over the years, such as loneliness in the urban landscape, the relationship between people and nature and the human footprint on our environment, transforming over the years, my own perception of the object of my gaze, to remain as still reminders of a single moment.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Carolyn Monastra: Divergence of BirdsFebruary 2nd, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Yi Wan Gyo: Nirvana-Beyond DarkJanuary 13th, 2026