Charlotte Woolf: 2018 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention

Congratulations to Charlotte Woolf for her Honorable Mention nod in the 2018 Lenscratch Student Prize Awards and for receiving her MFA from Purchase College, State University New York. I have had the privilege of following Charlotte’s trajectory over the past years and am so happy to celebrate her project, More Water Under the Bridge. Since graduation, Charlotte has been assisting Eric Gottesman with his studio practice in addition to running social media for Eric and Hank Willis Thomas’ collaborative project For Freedoms, during their 50 State Initiative campaign. This summer, Charlotte will be attending the Catskills Creative residency run by EcoPracticum in August, follow by the Wassaic Project residency for the month of September.

Charlotte Woolf (b. Greenwich 1990) is an interdisciplinary artist and educator with a focus on photography raised in Charlotte, North Carolina and based in Rye Brook, New York. She received her BA in Studio Art and Women’s & Gender Studies from Kenyon College and her MFA at SUNY-Purchase College of Art+Design.

Woolf has worked as a photographer around the country, including Chicago, IL, Park City, UT, Charlotte, NC, and New York, NY. She has also worked on farms in Maine, North Carolina, and Ohio – experiences which inspired her to attend ACRE (Artists’ Cooperative Residency and Exhibitions) in rural Wisconsin in 2013. In summer 2017 Woolf attended SOMA’s Summer Residency in Mexico City based around the theme of notions of authority in the art world. In September 2018 she will be in residence at the Wassaic Project in upstate New York. Woolf’s work has been exhibited in Chicago (ACRE Projects, Johalla Projects) and New York City (AIR Gallery, Local Projects, Equity Gallery).

Characterized by an acute attention to gender, Woolf aspires to continue her work not only through her camera lens, but also through radical politics and community based projects.

Woolf’s documentary style project Women in Agriculture (2011-2013), observed the livelihood family farms in Ohio and Wisconsin. The IUD Project (2015-current), focuses on women’s health and bodily autonomy during the Trump era through online community. Woolf’s long-term project More Water Under the Bridge (2014-current) is a response to her father’s death, interweaving her personal patriarchal legacy in construction of the United States in the 20th century. Through dealing with themes of family and power, her work reflects parallels between the failing infrastructure of the United States both physically and politically.

More Water Under the Bridge

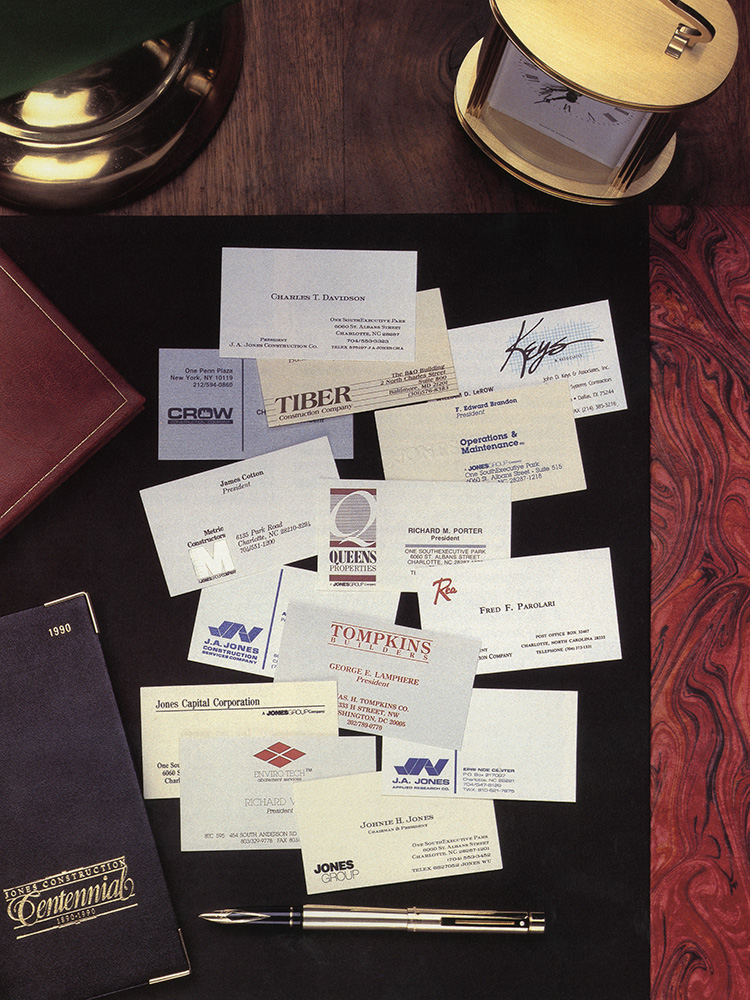

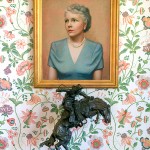

The subject on my mind in 2018 is: when great men fall, what is left behind? What will happen when the men who ruled the world are gone? Enter my work … In our contemporary version of culture wars, I examine the rubble of my family’s construction company which was an industry giant in the 1900s and went defunct in 2003. From my perspective as a queer woman who grew up with traditional values in North Carolina, I know what it’s like to not fit in, putting on a mask to play the part – I am critical of existing social norms. My interests in gender, power, and infrastructure has lead me to be a photographer, combining my photographs with archival sources, video and objects related to my family’s legacy in construction.

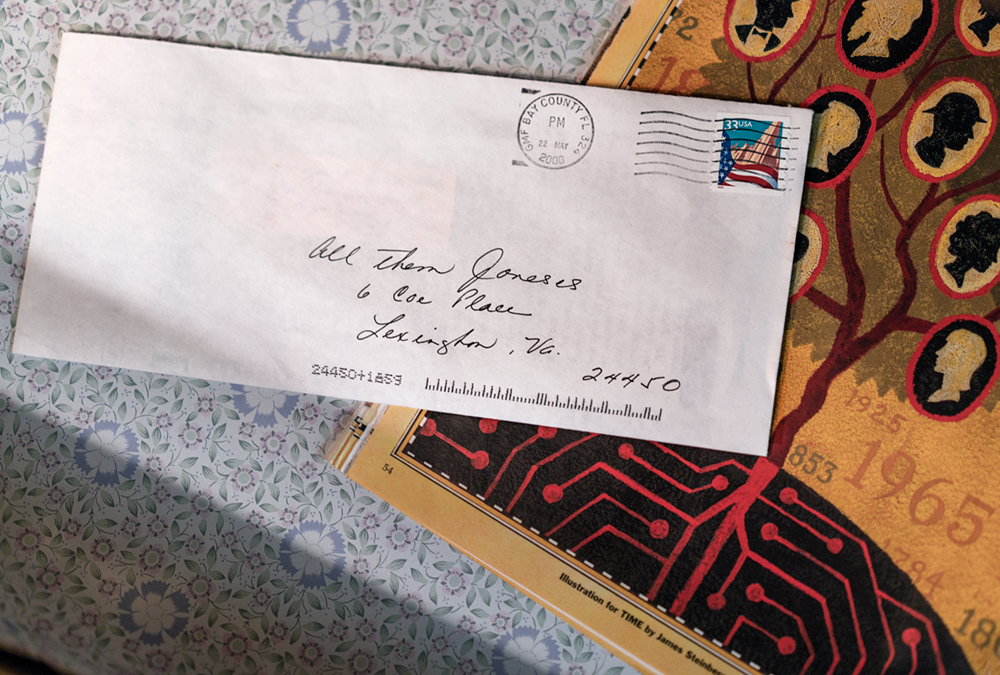

When my father passed away in 2014, his final piece of advice was to “let more water run under the bridge.” My father was a civil engineer, working between New York and North Carolina for over thirty years. Cryptic as it was, this has stuck with me as I have moved through the waves of grief and onward in my life finding meaning. Like a detective looking for clues, I have found the symbols in my life to place meaning on the advice through my work: making photographs and digging in the archive.

In my photographs, I am a seeking mystical solutions to unanswered questions about my life and family, a history just out of reach. I am searching for clues, following the light towards symbols (circles, flowers, books, chairs, hands) and connecting the dots. My questions become more complicated as I reach the center and realize there may never be an answer to death and decay. In a way, these questions link together like stars in a constellation. You can’t see the whole sky at once. In Eduardo Cadava’s Words of Light, Cadava aligns Walter Benjamin’s oeuvre with the history of photography, writing, “Photography is a mode of bereavement. It speaks to us of mortification. Even though it still remains to be thought, the essential relation between death and language flashes up before us in the photographic image.” Cadava continues” The history of photography can be said to begin with an interpretation of the stars.” Thus, in my work I often am looking through translucent layers, like a magnifying glass, window, mirror, and even water. Shooting through the camera lens adds another layer of glass, all creating distance between myself and the narrative as I rewrite my own interpretations of the family story by examining what remains.

By combining digital and archival materials, I create a sense of multiple generations going on at once in a room – something I always felt growing up with a father born in 1933 and a mother born in 1958. Furthermore, as a child of the nineties, I grew up during the teetering out of analog and the bitter takeover of digital photography. Questioning the originally of photography – thus the appropriated pictures are just as mine as Sherrie Levine’s Walker Evans was hers, my sizing, enlargements through scanning, and contextualization reclaims them into my own history giving them new meanings. Through this process of selection and enlargement, I am dealing with the presence or absence of the original source. In so doing, I weave the web of my family history from my own perspective. – Charlotte Woolf

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Nick Tarasov: 2018 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable MentionJuly 15th, 2018

-

Lindley Warren: 2018 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable MentionJuly 14th, 2018

-

Jasmine Clarke: 2018 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable MentionJuly 13th, 2018

-

Charlotte Woolf: 2018 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable MentionJuly 12th, 2018

-

William Douglas: 2018 Lenscratch Student Prize Third Place WinnerJuly 11th, 2018