Southbound: Photographs of and about the New South, Day 3

On the third day of our weeklong feature of Southbound: Photographs of and about the New South, the images are accompanied by an essay authored by Eleanor Heartney. Eleanor is a contributing Editor to Art in America and Artpress and has written extensively on contemporary art issues for such other publications as Artnews, Art and Auction, The New Art Examiner, the Washington Post and The New York Times. She received the College Art Association’s Frank Jewett Mather Award for distinction in art criticism in 1992. Her books include: Critical Condition: American Culture at the Crossroads (Cambridge University Press, 1997); Postmodernism (Cambridge University Press, 2001); Postmodern Heretics: The Catholic Imagination in Contemporary Art (Midmarch Arts Press, 2004); Defending Complexity: Art, Politics and the New World Order (Hard Press Editions, 2006) and Art and Today (Phaidon Press Inc., 2008), a survey of contemporary art of the last 25 years from Phaidon. She is a co-author of After the Revolution: Women who Transformed Contemporary Art(Prestel Publishing, 2007), which won the Susan Koppelman Award. Heartney is a past President of AICA-USA, the American section of the International Art Critics Association. In 2008 she was honored by the French government as a Chevalier dans l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres.

Salute to the Widows of Four North Carolina Soldiers, 2005 From the Southern Cause series Hollywood Cemetery, Virginia © Thomas Daniel

Photography, Poetry, and Truth – Eleanor Heartney

In considering examples that range from the so-called spirit photographs of the nineteenth century, whose doctored negatives purported to “prove” the existence of life after death, to today’s digitally altered Facebook images that place celebrity heads on compromised bodies, one can see that photography’s relationship to truth has always been somewhat tenuous. Documentary photography and its cousin photojournalism, in theory more reliable, have long been the tools of social crusaders and political activists intent on bringing us evidence of the real face of war, the gritty feel of poverty, and the evidence of crime and political malfeasance. Yet despite our desire to believe what we see in photographs, we know in our hearts that complete photographic veracity is an illusion. There is always an element of subjectivity and even deception in the most apparently objective images. A few cases in point: Renowned Civil War photographer Mathew Brady rearranged corpses on the battlefield to create more aesthetic compositions, Robert Capa staged his iconic photograph of a dying Republican soldier in the Spanish Civil War, and Walker Evans added an alarm clock to his photograph of a tenant farmer’s mantelpiece. Even when details are not consciously altered, photographers impose their biases through selection. As Susan Sontag remarked about photographers involved with the Works Progress Administration (WPA) project, they took dozens of images “until satisfied that they had gotten just the right look on film—the precise expression on the subject’s face that supported their own notions about poverty, dignity, and exploitation as well as light, texture, and geometry.”[i]

[i] Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1973), 4.

Big Black River Bridge, Mississippi, 2013. From the Broken Land series. Hinds County, Mississippi © Eliot Dudik

If this lack of absolute verism is true for historical photographs, it is even truer in the digital era when technological tools make manipulation of photographic images both effortless and seamless. These technical advances coincide with a growing ambivalence toward objectivity, further blurring the line between fact and fiction. We live in a time of “fake news,” “alternative facts,” and “truthiness,” the latter term coined by comedian Stephen Colbert to suggest the condition of something that feels true, even if it actually isn’t. Both academics and ideologues argue that reality is a construct and history a narrative written to advance preexisting political and social agendas. In this climate the traditional aims of documentary photography are increasingly met with suspicion and derision.

Fire Hose Baptism, 2013. From The Invisible Yoke, Vol. III: The Seven Cities series Newport News, Virginia © Matt Eich

Homecoming Kiss, 2012. From TheInvisible Yoke, Vol. III: The Seven Cities series Norfolk, Virginia © Matt Eich

Hot Afternoon, 2010. From The Delta: A Journey through the Deep South series. Willow Island, Mississippi River © Magdalena Solé

Family on Porch,2010. From The Delta: A Journey through the Deep South series. Lambert, Mississippi © Magdalena Solé

Southbound brings together fifty-six photographers who use their medium to probe the complexities of the American South. Only some of the artists here are documentary photographers in the strictest sense, but they all owe a debt to that genre. Many are directly influenced by figures like Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, and Gordon Parks, and a number have actually followed in the tracks of their idols, exploring the same or similar communities, locales, and themes. At the same time, they are keenly aware of the photographer’s role in shaping reality and of the slippery nature of photographic truth in contemporary times. Thus we might ask: What is the proportion of “fact” to subjective vision, political ideology, stereotype, and deliberate deception in the photographs on display? What or whose South do these photographers present?

Recent controversies over the display of Confederate monuments and symbols reveal the unsettled nature of Southern history. In the images here, one feels a tension between, on one hand, the powerful mythology of the Old South, described by William Faulkner as a “make-believe region of swords, magnolias, and mockingbirds,”[i] and, on the other, a history that includes still-vivid scars from the Confederacy’s defeat in the Civil War, the legacy of slavery, the persistence of rural poverty, and the scourge of class and racial tensions. The South of today floats between these conflicting visions of past and present. Photographer Mark Steinmetz describes the dilemma: “Most contemporary photographers of the South I think go a bit overboard in making the South seem like an overly gothic, romantic place, though there might be a few photographers who go overboard in the opposite direction by depicting the American South through a ‘new topographic’ prism that makes it seem indistinguishable from, say, the Belgian/German border. I love the South for the weeds growing through the cracks of its sidewalks, for its humidity and for its chaos.”[ii]

Steinmetz’s philosophy recalls German filmmaker Werner Herzog’s assertion about the nature of documentary film. In his Minnesota Declaration, he stated: “There are deeper strata of truth in cinema, and there is such a thing as poetic, ecstatic truth. It is mysterious and elusive, and can be reached only through fabrication and imagination and stylization.”[iii]

[i] William Faulkner, The Sound and the Fury, 2nd ed. (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1993), 229.

[ii] “Interview with Mark Steinmetz,” Ahorn Magazine, no. 5; http://www.ahornmagazine.com/issue_5/interview_mark_steinmetz/interview_steinmetz.html.

[iii] Werner Herzog, Minnesota Declaration: Truth and fact in documentary cinema (Minneapolis, Minnesota: Walker Art Center, April 30, 1999.)

Johnson City, Tennessee, 2004 © Mike Smith

The photographers in Southbound present a variety of strategies for getting at poetic truth. One widely practiced approach might be described as, Engage but also critique clichés. One of the most powerful of these is the trope of agrarian poverty. Photographers funded during the Depression by the WPA program, and later by magazines like Time and Life as part of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty, saw themselves as shock troops in the effort to expose the depth of destitution in Appalachia. Although they revealed real problems, in retrospect they also placed an indelible stamp on this region. Shelby Lee Adams, who was born in eastern Kentucky, struggles with this legacy in his own work. He notes that, as an adolescent, he was charged with assisting War on Poverty photographers, and he later felt that he and his community had been exploited. He remarks, “It seemed little consideration was given to the people’s feelings or the deeper life they actually lived and certainly the culture was considered and seen only one way—poor…. That sense of betrayal affected the entire region, not just me. It was an embarrassment to all and still troubles and affects many today.”[i] In his own photographic work, Adams struggles to provide a more rounded picture of the people and culture of Appalachia, creating portraits of individuals that preserve their humanity and dignity.

[i] Roger May, “Looking at Appalachia | Shelby Lee Adams—Part One,” Walk Your Camera (September 7, 2012); http://walkyourcamera.com/looking-at-appalachia-shelby-lee-adams-part-one/.

Green Mosque ,2006. From the Theater of War: The Pretend Villages of Iraq and Afghanistan series. Camp Mackall, North Carolina © Chris Sims

Casualty, 2005. From the Theater of War: The Pretend Villages of Iraq and Afghanistan series. Fort Polk, Louisiana © Chris Sims

The American South is a subject rich in contradiction and fraught with tension. Tamara Reynolds could be speaking for many of the photographers represented here when she says, “I cringe at how the country has stereotyped the South as hillbilly, religious fanatic, and racist. Although there is evidence of it, I have also learned that there is a restrained dignity, a generous affection, a trusting nature, and a loyalty to family that Southerners possess intrinsically. We are a singular place, rich in culture, strong through adversity. We are a people that have persevered under the judgment of the rest of the world. Ridiculed, we trudge carrying the sins of the country seemingly alone.”[i]

In On Photography, her classic meditation on the medium, Susan Sontag says, “To collect photographs is to collect the world.”[ii] This exhibition is part of that effort. There are so many faces here—young, old, white, black, Hispanic, grizzled, clean, careworn, pampered. So many landscapes—pitted country roads, threadbare main streets, expansive cotton fields, urban thoroughfares, mysterious bayous, sun-dappled swimming holes, manicured suburban lawns, disrupted waterways. So many reminders of history and markers of mortality—Confederate flags, historic churches, magnificent plantation houses, derelict trailers, dilapidated shacks. Revealed here is the dark side of the human soul, but also flashes of hope and happiness bursting through in musical celebrations, joyful communal rituals, and dusky skies darkened with flocks of birds. Represented in these photographs are personal visions and public spectacles, histories that were and histories that might have been. Together they create a mosaic that approaches reality, a South that is multifarious, and a truth that is manifold.

[i] Aline Smithson, “Tamara Reynolds: Southern Route,” Lenscratch (July 31, 2013); http://lenscratch.com/2013/07/tamara-reynolds-southern-route/.

[ii] Sontag, 1.

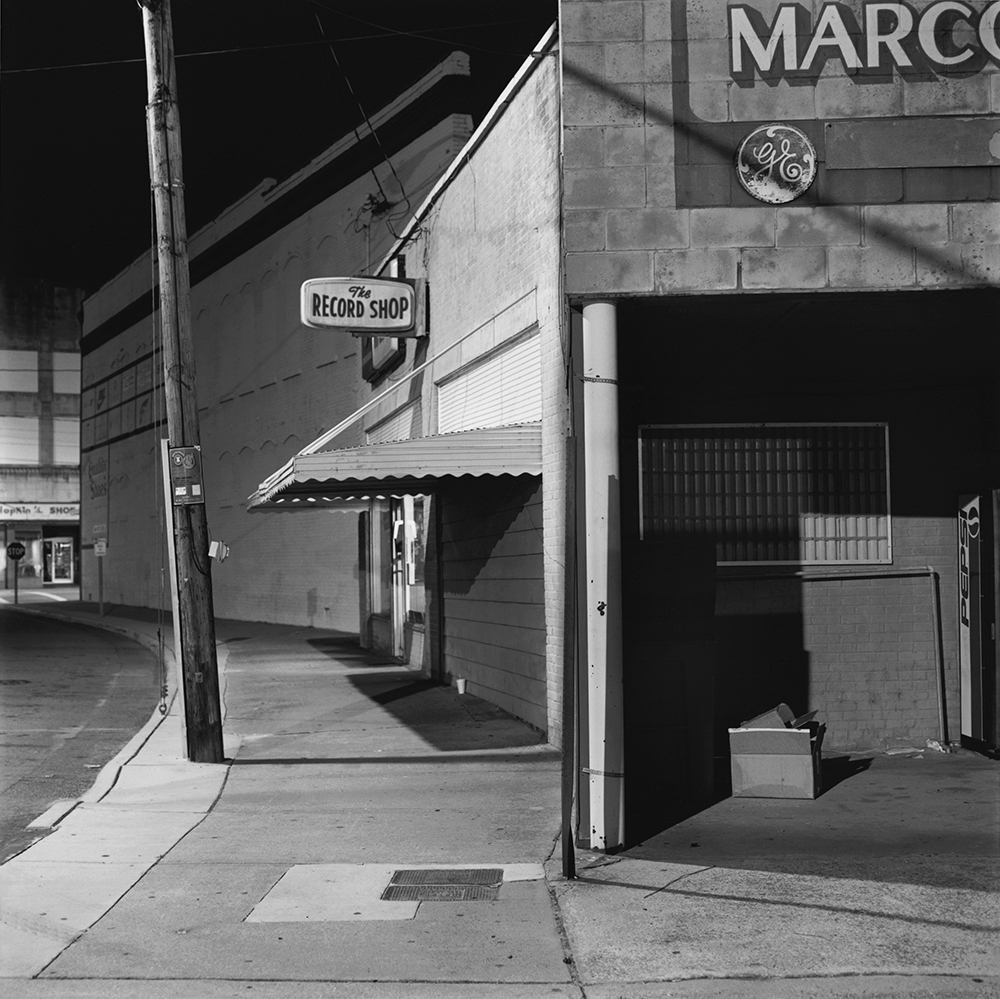

Williamston, Martin County, North Carolina,1998. From the Photographs from North Carolina series. Martin County, North Carolina © David Simonton

Johnston County, North Carolina,1998. From the Photographs from North Carolina series Johnston County, North Carolina © David Simonton

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Kevin Cooley: In The Gardens of EatonJanuary 8th, 2026

-

William Karl Valentine: The Eaton FireJanuary 7th, 2026

-

Sean Stanley: Ashes of SummerJanuary 6th, 2026

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026

-

Andrew Lichtenstein: This Short Life: Photojournalism as Resistance and ConcernDecember 21st, 2025