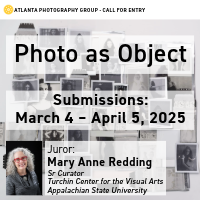

Thomas Alleman: Social Studies

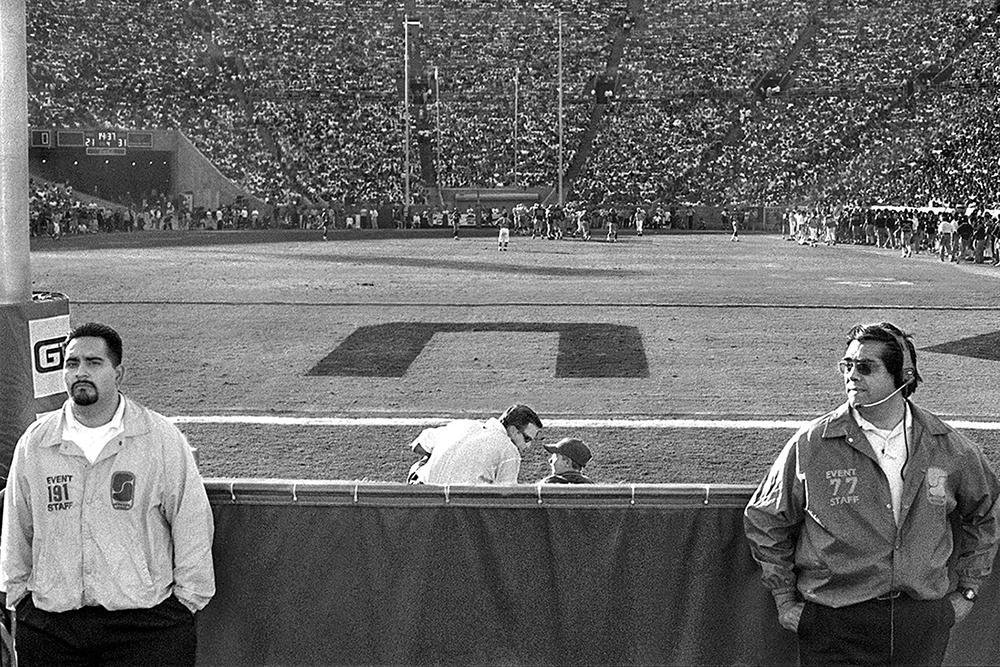

I never get tired of looking at Thomas Alleman’s remarkable photographs. His curiosity takes him into worlds personal, familiar, and unknown, and no matter the destination, he finds gold where ever he points his lens. His powerful project about his mother, The Unwinding garnered him a Top 50 nod in Critical Mass some years back. At the core of his abilities are two things–he is a humanist and has a history of getting the story, with a legacy of traversing streets and landscapes with laser sharp curiosity. Today we feature his project, Social Studies, an 18-year quest to find his photographic voice at the beginning of his stellar career.

Thomas’ work is being celebrated at the Los Angeles Center of Photography‘s STREET WEEK this week. Thomas will be teaching a workshop on the streets of Los Angeles on February 7th and later that evening his photographs will be on exhibition at the 6th Annual Street Shooting Around the World exhibition where he garnered 1st Place in the Series Competition (and $1000), juried by David Gibson. On February 8th at 4:30pm, Thomas will be speaking about his work at LACP.

Thomas Alleman was born and raised in Detroit, where his father was a traveling salesman and his mother was a ceramic artist. He graduated from Michigan State University with a degree in English Literature. During a fifteen-year newspaper career, Tom was a frequent winner of distinctions from the National Press Photographer’s Association, as well as being named California Newspaper Photographer of the Year in 1995 and Los Angeles Newspaper Photographer of the Year in 1996.

As a magazine freelancer, Tom’s pictures have been published regularly in Time, People,Business Week, Barrons, Smithsonian and National Geographic Traveler, and have also appeared in US News & World Report, Brandweek, Sunset, Harper’s and Travel Holiday. Tom has shot covers for Chief Executive, People, Priority, Acoustic Guitar, Private Clubs, Time for Kids, Diverse and Library Journal. Tom exhibited “Social Studies”, a series of street photographs, widely in Southern California.

“Sunshine & Noir”, a book-length collection of black-and-white urban landscapes made in the neighborhoods of Los Angeles, had its solo debut at the Afterimage Gallery in Dallas in 2006.Subsequent solo exhibitions include: the Robin Rice Gallery in New York in 2008 and 2013; the Blue Sky Gallery in Portland, OR in 2009 and 2015; the Xianshwan Photo Festival in Inner Mongolia, China, in 2010; and the Duncan Miller Gallery in Los Angeles, February 2013. “The American Apparel” debuted at the Redline Arts Center in Denver in 2015. Finally: Fifty-three of Tom’s photographs of gay San Francisco, shot between 1985 and 1988, debuted at the Jewett Gallery in San Francisco in December, 2012, under the title, “Dancing in the Dragon’s Jaws”. The workshops Tom teaches at the Los Angeles Center of Photography include “The Photographer’s Eye” and “Photographing in the Social Landscape.”

Social Studies

I studied literature in college and presumed I’d write novels afterward. As graduation neared, however, I was visited on several occasions by a stoner’s version of Marley’s ghost, who hectored my arrogance: I knew nothing at all, he told me, of life beyond the dormitories and little apartment blocks I’d lived in for four years, nothing at all of war or parenting or loss or the workaday life of regular people. What would I write about––smart-aleck rock philosopher’s like myself, wasting away at a teacher’s college in mid-Michigan? (Not the worst premise, I see now.) Chastened, I was persuaded to dip a toe into what some called “the real world”––to engage, for a while anyway, in some line of work that might acquaint me with the routines, experiences and attitudes of the wider world. For three years thereafter, I painted houses, worked for the local labor union, and waited tables in a popular Mexican restaurant, all while teaching myself, haltingly, to make photographs. I figured, if I could get a job at a newspaper someday, doing photojournalism, I might have access to “real life” on an even deeper level, which would later benefit the novelizing career I hadn’t yet given up on.

In those days before the internet, my sole inspirations came from the local library, where I found a tiny trove of untouched monographs among the dog-eared copies of Ansel Adams and Ernst Haas: Garry Winnogrand’s “Public Relations”; William Klein’s Aperture monograph; Lee Fridlander’s self-published retrospective from 1978; and Charles Harbutt’s “Travelog”. Even at first glance, I noticed the very liberal view of street photography they all shared: Besides working the bustling avenues in New York City, Friedlander shot parties with a ring flash, and Winnogrand did press conferences and rodeos, and Klein worked wide at demonstrations and Harbutt stalked suburban rituals like David Lynch with a press badge, creating ominous non-sequiturs. Those examples persuaded me that, however far I was from Midtown Manhattan, I could still avail myself of the communion parties, basketball matches and Labor Day Parades that proliferated there in Lansing, Michigan. Indeed, the first half-dozen pictures I made for “Social Studies”––which are still the foundation of that portfolio––were shot at a cocktail fundraiser, a spring prom, a boxing tournament, a county fair, a college graduation, and a Talking Heads concert. By terrific coincidence, the only tools I had on hand––a Minolta SRT 201 with a 28mm lens and a Vivitar 285 flash––were the perfect tools for those pictures; gear-wise, I was 100% outfitted for the job on Day One, utterly by accident.

Those tools aren’t to be underestimated. They define the photograph and shape the interaction between photographer and subject. Unlike the disposable, old-fashioned 50mm lenses that came with every camera in those days, that 28mm lens saw a wide, deep field, which a photographer had to wade through to get close enough for a decently intimate shot: to frame a couple from their waists to the top of their heads, a 50mm lens requires one stand about six feet away, while a 28mm halves that distance. That’s a lot of social space to cover, that three feet; that’s a whole different experience, standing within punching distance of one’s subjects. The relationship takes on a palpable edge; vectors of power, dominance and territory get weirder. Especially when the photographer introduces a blinding strobe to the scene. Certainly, the deployment of that tool is an act of aggression by the photographer, but it also makes her vulnerable in an unexpected way: she has revealed herself and her stratagems in a flash, and has become as much an object of interest and speculation to the wary subject as that subject had been to her, just a few seconds earlier. The rules-of-engagement are suddenly up for grabs.

But my interest in that Vivtar 285 wasn’t tactical; I didn’t knowingly wield it as a weapon in the here-and-now, while I shot. (Indeed, it hindered me in that, when I was a neophyte: after I’d fired off my first frame, everyone knew where I was, and they all sidled away like rabbits while I fumbled with the focus and exposure of my next shot, as if I were loading a musket.) The actual and obvious virtue of that strobe was not in-the-moment but on the negative: its use re-created the world of the room, by overwhelming the practical and natural illumination in there––the light from windows and lamps––with a source that was artificial, singular and authorial. It was white and bright, and it emanated from my camera position in a flat sheet and it bounced straight back to me, for my benefit alone. It pinned my subjects to the background, where the effects of that light on their hair and clothes and the planes of their skin could be studied in forensic detail; they were frozen in mid-gesture, half-glance. From the beginning, I’d intuited that necessity, to use lenses and light to create an unreal version of the hyper-real. As much as I could, I wanted to separate the photographs from the thing photographed, to create a two-dimensional document that referred to a three-dimensional source but which lived aside from it, a re-presentation.

By the end of the year, I understood almost everything I needed to know about that kind of work: the wide lens and the strobe technique, of course, but also the slyness and aggression, the thrust and move. More than that, I “got” the feel of those pictures, their anarchic attitude, the barely-controlled chaos. From studying my contact sheets obsessively––I slept with them all, inhaling their chemical stink––I realized that my most successful images were the ones that most disguised the nature of the event, that subverted the assigned narrative. The flash helped, by equalizing everything it touched, hiding the nominal subject amidst all the blasted data in the picture. The best shots filled the frame with disembodied shards of information, all of similar value to the non sequitur the picture had become.

I’d begun by aping those established photographers, but within months I believed I’d found a genuine voice of my own, for the first time ever. Twenty-five-years-old, I wondered if I’d ever get a foothold on some genuine artistic practice, and then, almost overnight in the winter of 1983, something had cracked open, and I knew I’d finally begun my real life. I spent the next 18 years working on “Social Studies”. As often happens with artists and projects, it ended with a whimper, inconclusively, as other interests and obligations oozed to the fore and stole away my time. After I made the eyeball picture in a train station in Vienna, I felt I’d come to the end of that relationship, that ambition and that way of seeing, and I turned my gaze elsewhere.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jordan Gale: Long Distance DrunkFebruary 13th, 2025

-

Looking Back: The Photography of Lewis WattsJanuary 18th, 2025

-

Marco Yat Chun Chan: Dollar Landscape and Savannah TreesSeptember 24th, 2024

-

Meryl Meisler: Street WalkerSeptember 14th, 2024

-

Photographers on Photographers: Kiên Hoàng in Conversation with Jamie Maxtone – GrahamAugust 15th, 2024