William Camargo: The 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize Third Place Winner

It is with so much pleasure that we announce the 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize 3rd Place Winner, William Camargo. He was selected for his outstanding project, Origins & Displacements: Making Sense of Place, Histories & Possibilities. William has recently received his MFA from Claremont Graduate University. His awards include a feature on Lenscratch, a mini exhibition on the Curated Fridge, and a Lenscratch T-shirt and Tote.

The jurors included Guanyu Xu – 2019 Student Prize Winner, Zora Murff- 2018 Student Prize Winner, Shawn Bush – 2017 Student Prize Winner, Drew Nikonowicz – 2016 Student Prize Winner, Elizabeth Moran – 2013 Student Prize Winner, Aline Smithson – Lenscratch Founder & Editor in Chief, Brennan Booker – Lenscratch Director of Special Projects, and Daniel George – Lenscratch Submissions Editor. We had a record number of submissions and the competition was fierce.

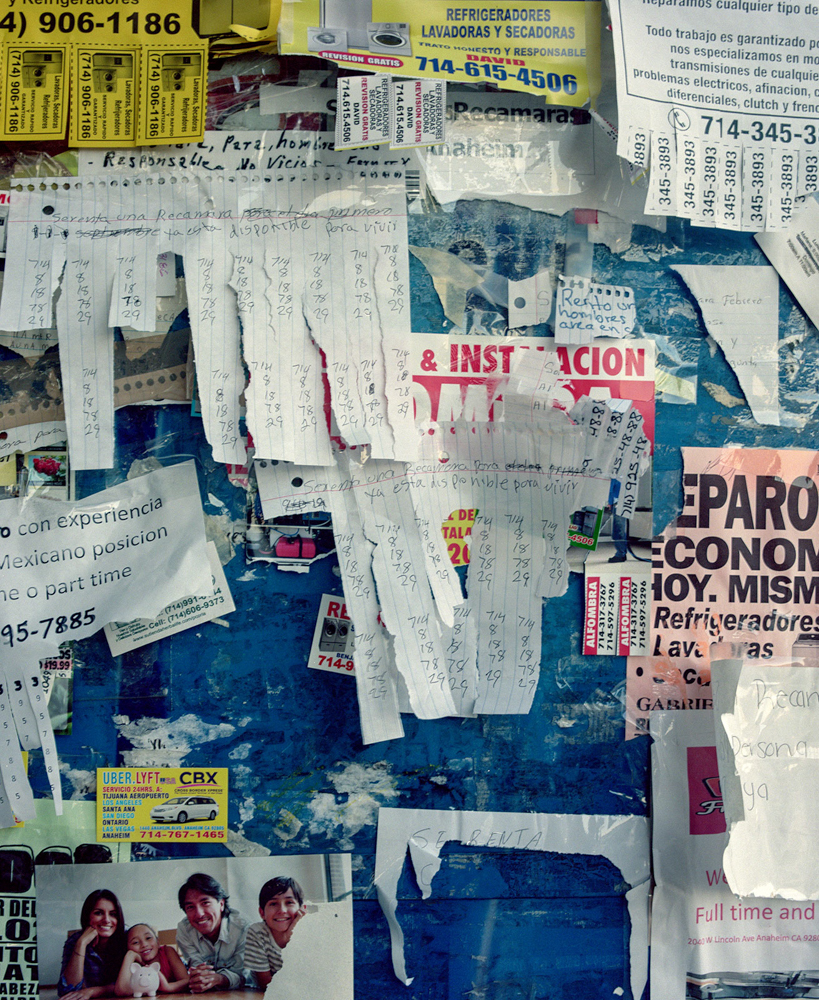

“Brown women used to pack oranges here,” reads a white rectangular sign obscuring the visage of its holder outside the Anaheim Packing House. The image’s composition, while simple and symmetrical, is steeped in metaphor and contains the undeniable symbology of violent erasure. Although brown hands clasping the corners of signs conveying similar messages continue throughout Willam Camargo’s series, Origins & Displacements: Making Sense of Place, Histories & Possibilities, so do traces of life perhaps not yet extinguished. Among these vestiges: freshly peeled orange skin, christian iconography, and a green comb placed just so. Then there are the people. Gentrification is ceaseless in it’s disregard to minority communities and yet Camargo’s portraits affirm and elevate the complex identities of Anaheim’s Latinx population. This visual affirmation stands in direct resistance to the cyclical narrative of systemic erasure at the hands of developers. It provides a moment of hope despite the inclusion of yet another sign this time reading “this area will gentrify soon.”

William Camargo is an Arts Educator, Photo-Based Artist and Arts Advocate born and raised in Anaheim, California, he is currently serving as Commissioner of Heritage and Culture in the city of Anaheim and working towards an M.F.A at Claremont Graduate University. He is the founder and curator of Latinx Diaspora Archives an archive Instagram page that elevates communities of color through family photos. He attained his BFA at the California State University, Fullerton, and an AA from Fullerton College in photography.

William has held residencies at Project Art, the Chicago Artist Coalition, ACRE, and at LA Summer held at Otis School of Art and Design. He has also participated in the New York Times Portfolio Review, NALAC’s Leadership(2018), and Advocacy(2020) Institutes. He is a current member of Diversify Photo an initiative started to diversify the photography industry. He was awarded the Friedman Grant from CGU and has given lectures at the University of Wisconsin-Parkside, Gallery 400(Chicago), University of San Diego, Cal State Long Beach, the Claremont Colleges, USC Roski School of Art, among others.

Additionally, his work has been shown at the Chicago Cultural Center, Loisaida Center(New York), the University of Indianapolis(IN), Mexican Cultural Center and Cinematic Arts(Los Angeles), Stevenson University(Baltimore), The Cooper Gallery of African and African American Arts at Harvard, Irvine Fine Arts Center, and upcoming at the Pheonix Art Museum and Salz Pollak Atrium Gallery located at Cal State Fullerton.

Origins & Displacements: Making Sense of Place, Histories & Possibilities

Origins & Displacements: Making Sense of Place, Histories & Possibilities

My artistic practice addresses issues of gentrification, Chicanx/Latinx histories in a city, and the systemic erasure of Brown people through the use of counter-narratives that amplify and extirpate hegemonic structures in local city narratives. Using photography, installation, political public performances, community archiving, and my role as an arts-based educator, I negotiate the legacies and disempowerment of Brown people in my hometown of Anaheim, California. I respond to found archives of the city through a historical art praxis that manifests as series-based artworks and strategies that address geographic place. Working with historically underrepresented narratives means dealing with the effects of systematic erasure, and implementing a critical pedagogical approach with room for further investigation of forgotten stories. By using hyperlocal histories, legacies, and contemporary news stories, I confront and challenge social constructs that are placed upon a city with historically racist policies and ideologies. I do this through liberatory actions that provoke new interpretations and elevates people’s hidden histories to the forefront. These issues of erasure, structural racism, and displacement become universal to other places and histories with similar power structures.

As a visual artist, art advocate, community archivist, and educator who examines structures of erasure, I continue to negotiate with placemaking, belonging, and constructed borders. For this reason, I use my own Brown body, one that was born and raised in Anaheim, to conduct these interventions. In the photographic body of work titled Yo, There Is A Bunch of Brown Folks On This Side, I place myself in front of a brown brick wall holding up a white sign that reads, “On This Side of the Wall Is a Predominantly Brown Working Class Neighborhood.” Using historical texts and contemporary stories, I aim to establish a connection in which the same forms of injustices are repackaged through language and neoliberal policies. The language in Yo, There is a Bunch of Brown Folks On This Side states “On This Side of the Wall Is a Predominantly Brown Working Class Neighborhood,” was found in a 2017 article in the Los Angeles Times about the city of Anaheim. Knowing that the demographics of the neighborhood are a majority of Brown(Mexican/American/Latinx) people, I inserted the word Brown to indicate the media’s reluctance to say it was also a racial issue. In the series An Attempt to Stop Flipping Houses, I document myself taking down house flipping signs throughout my neighborhood, keeping up with a system I created, of doing work in one geographic place. The impetus for this work has been mine and my community’s lived experience of gentrification and was created in hopes of making a dent in the predatory practice of house flipping. A method that displaces mostly Black and Brown people in communities of color.

In the photographic work titled After Stephen Shore but in Penquin City and Paisa, a continuation of my documentation of Anaheim, I place myself within the canon of the New Topographics in order to critique what I believe is the whiteness and banality of the genre and medium. This body of work deals with canonical issues in epistemic injustice that looks past and present Brown photographers, and more in-depth with testimonial injustice in which Brown perspectives in photography are overlooked or ignored.

My approach to documentation means working with the community and spending time researching local and concealed histories to create a collective meaning and validate the accounts of Brown people as knowledge. – William Camargo

Tell us about your growing up and what brought you to photography?

Growing up, a cheap plastic camera was always around, mostly the disposable cameras, and then my family upgraded to a longer-lasting point and shoot. I noticed something as an adult that there wasn’t many photos of me as a youth, I asked my parents and it turned out I would grab the camera and just photography away, sometimes taking several rolls without their permission. Growing up in public housing in the ’90s was something that you tend to see a lot of but what you see is mainly violence, trauma, and struggle, I believed that the images that came within were those of joy, triumph, and victory, and that gravitated me to step into archiving family photographs not only from mine but of the Latinx Diaspora. My first photography class was at my high school and shout out to Mr. Royster in Anaheim who upgraded me to an SLR one of the three he had for students. I didn’t realize that this class would do anything to me, to be honest, I took it because it was my senior year and didn’t want to put any work my last year in High School, I didn’t see a future in it or even a future in academia in general. After that class, I decided to change the path of my life and pursued it with a bit more intent. It took a while being a first-generation college student and son of immigrants my parents thought the best plant would be to become a doctor, lawyer or any career that would help us come out of poverty, but photography wasn’t letting me go that way.

We are always considering what the next generation of photographers are thinking about in terms of their careers after graduation. Tell us what the photo world looks like from your perspective. What you need in terms of support from the photo world? How do you plan to make your mark? Have you discovered any new and innovative ways to present yourself as an artist?

I would love to see the photo world be more equitable, during times like these, not only to uplifts Black photographers but after the front-page headlines are gone, how can we as non-Black photographers keep supporting them? Not only are there so many great Black photographers out there but they can photograph more than the medias race stories. We have seen the ugly photography has done to Black and POC communities, from eugenics and so on, that it is time to confront that issue. More BIPOC folks need to be in positions of leadership because photography is a tool for social justice. Career-wise we seem to be great at doing many photography careers, from photo editing, editorial to education, which all are important, imagine how we can challenge the cannon in photography, be able to deconstruct it and see more BIPOC folks in slideshows and creating lessons plans around Black and POC photographers that changed genres. I think it is time for the older generation to give up their positions of power in institutions across the photo world if they are really are in solidarity with Black and POC photographers then the real test is giving up that power. There needs to be a reconstruction of places and that is what kind of support the photo world needs to give to us. Making a mark is a loaded question, in my world becoming a world-famous artist isn’t the ultimate goal, my goal is to make space for other folks, to be able to teach the works of Laura Aguilar, Paul Sepuya, Leonard Suryajaya, Irene Reece, and other great photographers that destroy the canon and turn it upside down, that battle epistemic oppression with their work, that is how I want to make my mark, and if my works succeed then be it, but I wouldn’t be upset if it doesn’t.

Much of your artwork also functions as activism. How did you arrive at this intersection?

I spent many years working as a photojournalist in Los Angeles, Chicago, and Mexico and got fed up with the industry. How it sees BIPOC folks, most of the time, I was photographing stories of violence. As a person of color, it got me thinking a lot about my position as an image-maker, and how the role of a photojournalist and photography can be used as a tool for oppression as well. Seeing all that trauma, pain, and violence, that was also there growing up in a community of color, I felt that there were other ways to turn the camera into a tool for social justice. For me to tell the same stories, I did not have to be in the “front lines.” I could be in the front lines some other way, that is not to say photojournalist can be transformative, but at that time I thought that me physically organizing and being present without the camera was more powerful. I then started my practice of doing works that talked about displacement, violence, and other issues that are important to me, and at times organizations would ask to either donate some work for mutual aid funds. Knowing that in social justice movements art was always there to help a cause, I was thinking of the Black Panther Party, Brown Berets, Indian American Movement, and the Young Lords their use of art in their movements helped propel some change.

I had thought that art and activism were meant to stay separate but then realized that the intersection of both of those was much more powerful together. This was all the while seeing the works of Maria Gaspar and the 96 Acre project she started that talked about incarceration, and For the People Artists Collective, which made posters for protests and currently has free downloadable posters from various artists that centralize Black Lives Matter. That is when it really started seeing those two things work together so beautifully and realizing too that back home in Anaheim, this was a way to organize, making art that informs and allows it to be both art and activism.

Origins & Displacements: Making Sense of Place, Histories & Possibilities deals largely with gentrification and systemic erasure. How have you witnessed Anaheim transform over the years? Can you share a memory from your childhood alongside a recent experience to highlight this shift?

This body of work was first made several years ago during undergrad at Cal State Fullerton, while it has transformed a professor of mine and great artist Julie Orser, gave me this challenge to make images of my hometown, that project ended up being my undergrad thesis show. After that initial project, which was the first that made me look into issues in my city, I left Anaheim to Chicago for several years. I got involved in the fight against gentrification, which is a movement that is led by amazing Black femmes and other women of color, and I realized that this, too, was an issue in my hometown. In one of the works of Origins & Displacements was originated because of a park that I use to practice with my soccer team growing up had changed. after leaving and coming back, I went to that park thinking I could kick the ball around, but it had been turned into a dog park, and in that dog park is a statue of a police dog named Bruno while a less than 2 miles was the site of a police shooting of an unarmed Latinx man, who I went to high school with. Across the street, use to be various small business that would also support local soccer teams, and that was all gone, the city demolished it, and now are replacing it with luxury housing. That small section of the park had many memories, I took photos of my brother’s middle school graduation, they were really bad images, but I had made them and in a place that was special to my upbringing. I believe that gentrification is violence and is a new form of colonization.

How did education become a part of your practice? What do you believe your role is as an art educator?

I think education was always a part of my practice, but at the time, I just didn’t know it. While in undergrad, I would conduct photographic workshops at my old neighborhood schools, from then on, I continued to teach and taught in Chicago as well. Education and my art practice are mutual. I learn a lot from my students. I can see that the power of knowledge can be one of liberation, too, especially in the communities I was teaching, which always looked like the schools I went to as a kid. My role as an educator is one of liberation, of my freedom and the students too, I think art education and the system in which it currently lives in needs to be dismantled and built from the ground up, with Black art educators being in the forefront. I tend to always look at Bettina Love and Bell Hook’s books and other Black femme writers that look at education as freedom. The classroom can be a place of most radical change, that those spaces and as well as museum spaces can be places of liberation and imagining better worlds for BIPOC folks. Furthermore, as an art educator, a role I put on myself is to engage with the community. How can I bring their community into the space, how can I grow my list of BIPOC artist to build a curriculum around them? Going through public education and higher ed institutions, Latinx and Black artist were sometimes only taught as the “other” when in fact, they were artists who started movements but were always left out of that history.

Congratulations on your Lenscratch Student Prize! What’s next for you? What are you thinking about and working on?

Thank you for allowing me to show my work and giving me this platform, currently working on two exhibitions, and along with many other folks affected by Covid-19 plans sometimes don’t go your way, and that is okay. I plan to continue doing art education in my hometown in Anaheim, and elsewhere. I do plan on applying to a Ph.D. program in the future as well. I am also currently thinking of this Instagram conflict I had with John Divola, which is a longer conversation so I will just leave it at that. I have been delving into a lot of reading and consuming my photo books. While in quarantine I have also made new works, that I have put on my website and Instagram and hope to exhibit some of those in the near future. But also have been thinking a lot about the canon of photography, and the violence and trauma that at times those figures invoke, and how can we be critical of those works, which again leads to the conflict I had with a canonical figure in photography.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Amrita Stützle: The 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize Winner Honorable MentionJuly 29th, 2020

-

Leah Schretenthaler: The 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize Winner Honorable MentionJuly 28th, 2020

-

Hannah Altman: The 2020 Student Prize Winner Honorable MentionJuly 27th, 2020

-

Lindley Warren Mickunas: The 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable MentionJuly 24th, 2020

-

William Camargo: The 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize Third Place WinnerJuly 23rd, 2020