International Peace Week: Rodrigo Abd: Civil War Exhumations

Isabel Chopen Zotoi walks with flowes to adorn the houses in “El Adelanto” village, Solola, where forensic antrophologists are exhuming skeletons in a mass grave where 12 persons were buried after being massacred by the Guatemalan army in 1982, Friday, Aug 31, 2007. Forensic antrophologists try to recover the remains of some 20 persons murdered, but 8 of them will not be exhumed yet because the owners of the lands where they were buried want to wait until they pick their corn crops before allowing the exhumkation work of the antrophologists. During the Guatemalan Civil war, more than 200.000 people were killed or dissapeared. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

In honor of the International Day of Peace and Peace Week, Lenscratch has partnered with the National Center for Civil and Human Rights to feature photographic projects highlighting the lasting impacts of war, conflict, and displacement. Lauren Tate Baeza, Director of Exhibitions at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights, is our guest editor.

Since 1981, the International Day of Peace has been observed annually on September 21st. Declared a day of nonviolence and cessation, the UN General Assembly unanimously voted for a holiday to increase public awareness of the perils of war and encourage educational programming on topics related to peace. With a persistent need to pool resources to combat the COVID-19 global health crisis, this year carries an added sense of urgency for conflict resolution.

Wars are fought by soldiers and rebels, but they spare no one. The compounding fallout often spans for generations. This week’s selections examine burdens inherited by families and other bystanders. The Guatemalan Civil War lasted from 1960 to 1996, when peace accords were signed between guerillas and the military dictatorship. The war left hundreds of thousands of civilians dead or disappeared, a disproportionate amount of which were indigenous Mayan groups and rural poor the military considered supportive of guerillas. Rodrigo Abd’s series, Exhumations, includes emotive depictions of the retrieval of remains found at mass gravesites and, more than a decade after the war, the ongoing process of reconciliation as forensics aid in trial proceedings and family members provide proper burials for their loved ones in accordance with cultural and ancestral tradition.

Photojournalists navigate worlds beyond our reach and report back with visual evidence crucial to ensuring dignity and human rights. Since World War II, documentary narrative photography has informed populations and influenced major policy decisions, resulting in interventions that combat human rights atrocities, send aid and relief to regions impacted by hunger and natural disaster, and galvanize support and protections for minority groups, as was famously accomplished during the American Civil Rights Movement. This week, therefore, we both honor photojournalists and commemorate the pursuit of peace.

The skeletons of two of nine men who were tortured and massacred allegedly with the Guatemalan Army during the civil war are seen in a mass grave in Uspantan, Quiche, Monday, August 3, 2009. Forensic anthropologists have begun to use DNA sampling and analysis to identify victims of human rights abuses committed during this country’s 36-year-long civil war that left 200.000 dead and 40.000 disappeared. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

Civil War Exhumations

Accords for a “firm and lasting peace” were signed in Guatemala in 1996, officially ending 36 years of civil war between leftist guerrillas and military dictatorships that left more than 200,000 civilians dead or disappeared. According to the Historical Clarification Committee (CEH), in the 1980s the Guatemalan Army identified groups of the Mayan population as the internal enemy, considering them to be an actual or potential support base for the guerrillas. The Army perpetrated 626 massacres in Mayan communities, which often resulted in the complete extermination of these communities.

During the last decade and a half, as fears of retaliation quell, family members seek to exhume the remains of their loved ones that lie in unmarked, common graves, and rebury them according to ancestral traditions. This provides the wandering soul with a resting place, and the family members with a grave to honor on the Day of the Dead.

Forensic expert testimony resulting from exhumations have proved essential to criminal proceedings in national courts seeking justice for the extrajudicial killings, massacres, disappearances, and genocide.

Guatemala, 2003-2011.

A forensic antrophologist works to exhume the body peasant killed by the army in 1982 during the civil war , Chucalibal, Quiche, , 130 kilometers west of Guatemala City, Tuesday, May 17, 2005. The Guatemalan Foundation for Forensic Anthropology oversaw the exhumation which was visited by family members of victims of violence from around the world, including relatives of victims of the September 11 attacks in the US. (Ap Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

Rodrigo Abd nació en Buenos Aires, Argentina, el 27 de octubre de 1976.

Su carrera como fotógrafo comezó en los periódicos La Razón y La Nación en Buenos Aires, Argentina, de 1999 a 2003. Desde 2003 ha sido fotógrafo del personal de Associated Press con sede en Guatemala, con excepción del 2006, cuando tuvo su sede en Kabul, Afganistán. Rodrigo ha trabajado en asignaciones especiales de AP.

Junto con otros fotógrafos de AP, se les otorgó el Premio Pulitzer 2013 por Fotografía de noticias de última hora por su trabajo sobre la guerra civil siria. Actualmente con sede en Lima, Perú, cubriendo principalmente la zona de Latinoamérica.

Rodrigo Abd was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on October 27, 1976.

His career as a photographer began in the newspapers La Razón and La Nación in Buenos Aires, Argentina, from 1999 to 2003. Since 2003 he has been a staff photographer for the Associated Press based in Guatemala, with the exception of 2006, when he was based in Kabul , Afghanistan. Rodrigo has worked on special AP assignments.

Along with other AP photographers, they were awarded the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Photography for their work on the Syrian civil war. Currently based in Lima, Peru, mainly covering the Latin American area.

A skeleton is seen next to indigenous clothes at a mass grave where 12 persons were buried after being massacred by the Guatemalan army in 1982 in “El Adelanto” village, Solola, Guatemala, Friday, Aug 31, 2007. Forensic antrophologists try to recover the remains of some 20 persons murdered, but 8 of them will not be exhumed yet because the owners of the lands where they were buried want to wait until they pick their corn crops before allowing the exhumkation work of the antrophologists. During the Guatemalan Civil war, more than 200.000 people were killed or dissapeared. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

Diego Luz Tzunux takes a picture with his cell phone of his brother Manul Lux Tsunux, who dissapeared in 1980, and now is being exhumated by forensic anthropologists, Uspantan, Quiche, Monday, August 3, 2009. Diego Luz Tzunux was tortured and masacred allegedly by the Guatemalan Army during the civil war. Forensic anthropologists have begun to use DNA sampling and analysis to identify victims of human rights abuses committed during this country’s 36-year-long civil war that left 200.000 dead and 40.000 disappeared.(AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

Cristina Alfaro Mejia, whose husband and daughter were killed by soldiers during Las Dos Erres massacre in 1982, holds a rose as waiting to the sentence in Guatemala City, Tuesday, Aug. 2, 2011. Four military officers were sentenced to 6,060 years in prison for being involved in the 1982 Las Dos Erres massacre that resulted in the killing of more than 200 people as part of a “scorched earth” effort to eliminate communities supporting insurgent groups during the height of Guatemala’s 36-year civil war. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

Relatives look to the bones of Gaspar Terraza Matom, around 10 years old, who was killed during a massacre made by the Guatemalan Army in 1981, Nebaj, around 300 km northwest from Guatemala City, Monday, June 9, 2008. After the exhumation of 76 villagers killed April 16, 1981, in Cocop, Nebaj, a forensic antropologists team made a cientific study of the bones and clothes of the massacred villagers in order to identified them. After more than 2 years of study, the antroprologists are giving the remains to their relatives, do they can make a burial in the comunity. During the 36 years of civil war in the country, around 250.000 people were killed or dissapeared.(AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

Juana Brito cries after preparing for the burial the skeleton of her brother who was killed during a massacre made by the Guatemalan Army in 1981, Nebaj, around 300 km northwest from Guatemala City, Monday, June 9, 2008. After the exhumation of 76 villagers killed April 16, 1981, in Cocop, Nebaj, a forensic antropologists team made a cientific study of the bones and clothes of the massacred villagers in order to identified them. After more than 2 years of study, the antroprologists are giving the remains to their relatives, do they can make a burial in the comunity. During the 36 years of civil war in the country, around 250.000 people were killed or dissapeared.(AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

The skeleton of one of nine men who were tortured and masacred allegedly with the Guatemalan Army during the civil war is seen in a mass grave in Uspantan, Quiche, Monday, August 3, 2009. Forensic anthropologists have begun to use DNA sampling and analysis to identify victims of human rights abuses committed during this country’s 36-year-long civil war that left 200.000 dead and 40.000 disappeared. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

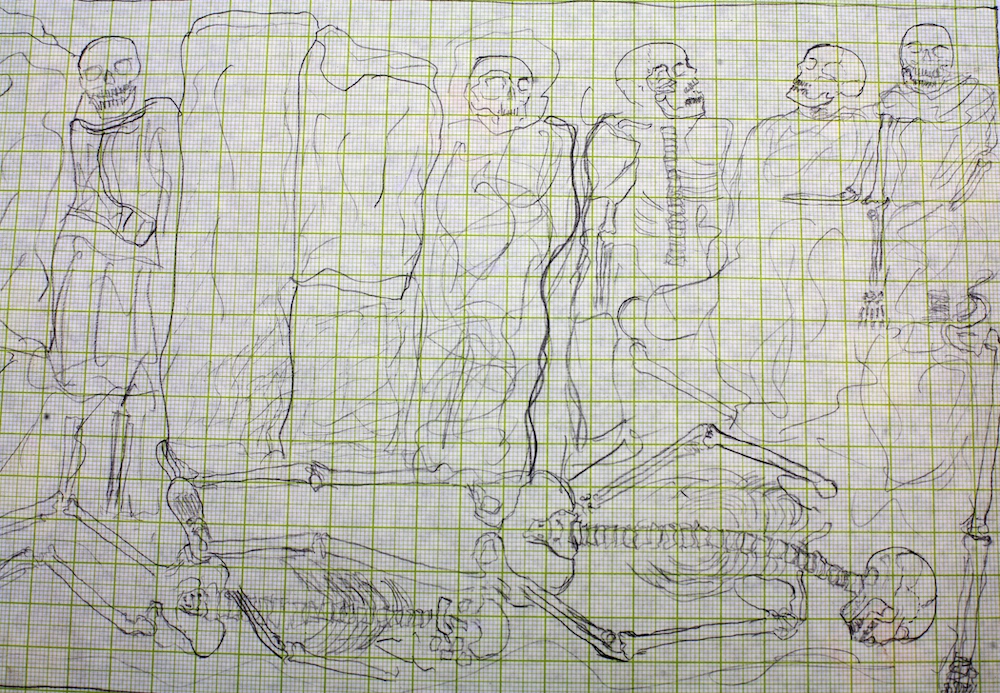

The drawing made by an antrophologist describes the mass grave where 12 persons were buried after being massacred by the Guatemalan army in 1982 in “El Adelanto” village, Solola, Guatemala, Friday, Aug 31, 2007. Forensic antrophologists try to recover the remains of some 20 persons murdered, but 8 of them will not be exhumed yet because the owners of the lands where they were buried want to wait until they pick their corn crops before allowing the exhumkation work of the antrophologists. During the Guatemalan Civil war, more than 200.000 people were killed or dissapeared. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

In this June 20, 2018 photo, a woman burns incense on the coffins with the remains of 172 people exhumed in a former military regiment in San Juan Comalapa, Guatemala. In a small town in Guatemala some of the 45,000 thousand disappeared during the civil war will now be able to rest in peace. The women of Comalapa, located in the department of Chimaltenango some 77 kilometers west of the Guatemalan capital, created a place to pay the missing from the war from 1960 to 1996 the tribute that the State has denied despite a request in that sense of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

Musicians perform during the burial of six members of a family killed during a massacre made by the Guatemalan Army in 1981, in Cocop,Nebaj, around 300 km northwest from Guatemala City, Monday, June 9, 2008. After the exhumation of 76 villagers killed April 16, 1981, in Cocop, Nebaj, a forensic antropologists team made a cientific study of the bones and clothes of the massacred villagers in order to identified them. After more than 2 years of study, the antroprologists are giving the remains to their relatives, do they can make a burial in the comunity. During the 36 years of civil war in the country, around 250.000 people were killed or dissapeared.(AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

Diego Matom dance next to the coffins of six members of their family killed during a massacre made by the Guatemalan Army in 1981, in Cocop,Nebaj, around 300 km northwest from Guatemala City, Monday, June 9, 2008. After the exhumation of 76 villagers killed April 16, 1981, in Cocop, Nebaj, a forensic antropologists team made a cientific study of the bones and clothes of the massacred villagers in order to identified them. After more than 2 years of study, the antroprologists are giving the remains to their relatives, do they can make a burial in the comunity. During the 36 years of civil war in the country, around 250.000 people were killed or dissapeared.(AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

A man carries a coffin of a villager killed during a massacre made by the Guatemalan Army in 1981, Cocop, Nebaj, around 300 km northwest from Guatemala City, Tuesday, June 10, 2008. After the exhumation of 76 villagers killed April 16, 1981, in Cocop, Nebaj, a forensic antropologists team made a cientific study of the bones and clothes of the massacred villagers in order to identified them. After more than 2 years of study, the antroprologists are giving the remains to their relatives, do they can make a burial in the comunity. During the 36 years of civil war in the country, around 250.000 people were killed or dissapeared.(AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

About the National Center for Civil and Human Rights

The National Center for Civil and Human Rights is a cultural institution and advocacy organization located in downtown Atlanta, Georgia. Powerful and immersive exhibits tell the story of the American Civil Rights Movement and connect this history to modern struggles for human rights around the world. The National Center for Civil and Human Rights has the distinction of being one of the only places to permanently display the papers and artifacts of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Events, educational programs, and campaign initiatives bring together communities and prominent thought leaders on rights issues. For more information, visit civilandhumanrights.org and equaldignity.org.

Join the conversation on @ctr4chr (Twitter), @@ctr4chr (Facebook), and @@ctr4chr (Instagram).

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

J. Lester Feder: The Queer Face of WarMarch 11th, 2026

-

L. Kasimu Harris: New Photography 2025: Lines of Belonging at MOMAMarch 10th, 2026

-

Kiana Hayeri: No Woman’s LandMarch 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026