The 2023 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Elena Bulet i Llopis

It is with pleasure that the jurors announce the 2023 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner, Elena Bulet i Llopis. Bulet was selected for her project, La balsa, and is currently attending the pursuing an M.F.A. at the Rhode Islands School of Design. The Honorable Mention Winner receives: $250 Cash Award and a Lenscratch t-shirt and tote.

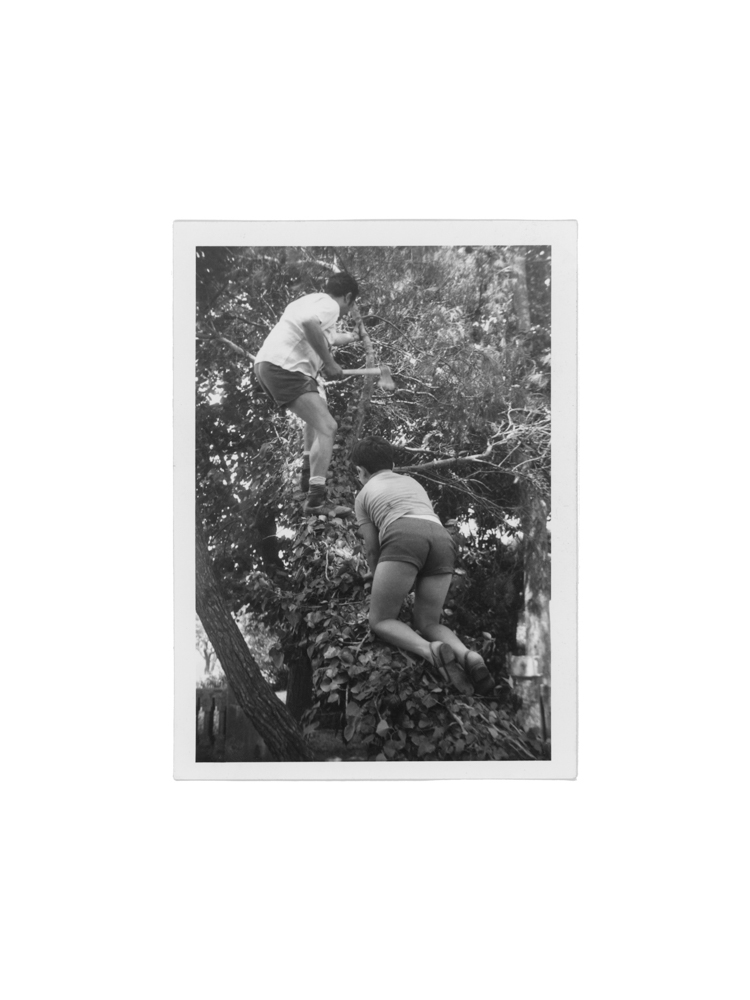

Elena Bulet i Llopis’ series, La balsa, tends to an intimate family history shrouded by the violences of Francoist Spain. The series collects archival family photographs alongside performed, revisited and reimagined scenes from Bulet i Llopis’–and her relatives’–remembered childhoods in Catalonia.

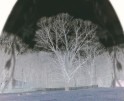

Amid the haunting but mostly absent backdrop of dictatorship and heteropatriarchy, La balsa proposes a meditation on “wounds,” “cracks” and “blanks” as sites of aching possibility. The series gestures toward corporeal histories through evidentiary marks: scars etched into skin, their ghostly reappearance as celestial tattoos, and the patterning of DNA in the wave and the color of hair. Such scars function as physical records–not unlike the photograph–and yet they also yield to sites beyond the “documentary.” La balsa brims with acts of performance, with speculative scenes that strain against the descriptive impulses of the camera: a gossamer-thin gown floats suspended in an arctic landscape; a silky void–a hole, a cavern–yawns above a precarious frame of false flowers. These scenes are magical in construction, but they are nonetheless unsevered from the material realities of lived experience, and they refuse to evade the problematic of present(ed) and absent(ed) bodies: the diaphanous gown recalls the absence of its owner; the silky orifice strategically diverts from the human figure escaping the edge of the frame. These pictures suggest that the polarities of harm–healing, fact–fabrication, document–performance, and body–specter are more deeply entangled and intimate than is comfortable to imagine.

La balsa also figures sites of tender but insistent contact: four hands tangled in a string game, two foreheads pressed together in grass, an arm splayed casually across a bare lower back. These representations of touch–of intimacy–gesture toward the tensions of proximity, one active between human bodies as well as between the present and history. Tending to history seems always to invite a haunting at the levels of desire and embodiment, and to this Bulet i Llopis confers: “How do we confront–and begin to weave–the unsaid, the suppressed, the broken, into emergent possibilities of being when so much of it preceded your own existence?” How does one deal with the desire to recover and redress history, when so many and so much of the lives entombed remain unknown? How does one come to terms with the gaps and the absences of un/official archives, when those crucial absences lay the foundation for one’s present embodiment?

Against the charged exercise of historiography–against a dictatorship’s administration of history and heteropatriarchy’s selective silencing–Bulet i Llopis works with archival gaps and the inherent discrepancies of memory. She revisits, reimagines and reconstructs sites of personhood and belonging; in the hairline fractures of uncertain histories, she finds the luminous potential of intimacy and play.

An enormous thank you to our jurors: Aline Smithson, Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Daniel George, Submissions Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Linda Alterwitz, Art + Science Editor of Lenscratch and Artist, Kellye Eisworth, Managing Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Alexa Dilworth, publishing director, senior editor, and awards director at the Center for Documentary Studies (CDS) at Duke University, Kris Graves, Director of Kris Graves Projects, photographer and publisher based in New York and London, Elizabeth Cheng Krist, Former Senior Photo Editor with National Geographic magazine and founding member of the Visual Thinking Collective, Hamidah Glasgow, Director of the Center for Fine Art Photography, Fort Collins, CO, Yorgos Efthymiadis, Artist and Founder of the Curated Fridge, Drew Leventhal, Artist and Publisher, winner of the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize, Allie Tsubota, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2021 Lenscratch Student Prize, Raymond Thompson, Jr., Artist and Educator, winner of the 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize, Guanyu Xu, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2019 Lenscratch Student Prize, Shawn Bush, Artist, Educator, and Publisher, winner of the 2017 Lenscratch Student Prize.

An enormous thank you to our jurors: Aline Smithson, Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Daniel George, Submissions Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Linda Alterwitz, Art + Science Editor of Lenscratch and Artist, Kellye Eisworth, Managing Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Alexa Dilworth, publishing director, senior editor, and awards director at the Center for Documentary Studies (CDS) at Duke University, Kris Graves, Director of Kris Graves Projects, photographer and publisher based in New York and London, Elizabeth Cheng Krist, Former Senior Photo Editor with National Geographic magazine and founding member of the Visual Thinking Collective, Hamidah Glasgow, Director of the Center for Fine Art Photography, Fort Collins, CO, Yorgos Efthymiadis, Artist and Founder of the Curated Fridge, Drew Leventhal, Artist and Publisher, winner of the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize, Allie Tsubota, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2021 Lenscratch Student Prize, Raymond Thompson, Jr., Artist and Educator, winner of the 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize, Guanyu Xu, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2019 Lenscratch Student Prize, Shawn Bush, Artist, Educator, and Publisher, winner of the 2017 Lenscratch Student Prize.

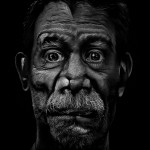

Elena Bulet i Llopis.(she/they) is a visual artist born and raised in Barcelona (1997). She uses still photography, experimental film, and archives to explore narratives related to intimacy, identity and trauma.

She has done projects in Spain, about women seeking asylum, in Chile, during the social outbreak, in Colombia, during the post-conflict and peace-building period and in New York, where she worked on stories about the LGTBQIA+ community and the ballroom scene.

She graduated in Journalism from the Autonomous University of Barcelona in 2020. During her Bachelor’s she also studied abroad in Prague, Czech Republic, where she worked doing cultural audiovisual reports for the Catalan TV program “Blog Europa”. She also did part of her undergrad at the University of Santiago de Chile. Since 2021, she has been studying in the United States. She graduated from the One-Year Certificate Program in Documentary Practices and Visual Journalism at the International Center of Photography in NY and she is currently studying an MFA in Photography at Rhode Island School of Design.

Her work has been published in several media such as “La Directa”, “Deriva”, “La Marea”, “diari Ara”, “Catalunya Plural”, “El Salto”, “El Diario de la Educación” or “El Jardí”. She has also produced and directed several audiovisual works, the last one, being the experimental documentary “Pretty” (2022).

Instagram: @ElenaBulet

La balsa

My grandma Mari, my mother’s mom, migrated from the south of Spain due to shortage and economic difficulties and built up a family in Catalonia. She died when I was three, and since then I have tried to find her in a yellow-flowered blanket that was at her house. Grandma Elvira, from my father’s side, is still with us, and she used to spend part of the summers in a house in the countryside with a pond. At first, the pond was used to water the surrounding agricultural fields. Decades later, it became the place where several generations of my family would swim together.

I began this project by looking at both of my grandmothers’ archives as visual articulators of place, belonging, and personhood. They showed the morality of a generation, in terms of what deserved to be included and what remained silent. But also were the basis for understanding the tensions that permeated their lives. People who grew up in times of postwar and dictatorship in Spain and who have been marked by heteropatriarchal violence from their partners.

To make the pictures, I investigate what it means to return to childhood as an adult. I perform activities my relatives used to do when they were young, like playing string games with their hands or collecting shells on the beach. I embrace the idea of play as a space where one can be imaginative and vulnerable, but also a space where one can be hurt.

There is a lot of pain that comes from the demands of heteronormative institutions, wounds that are unconsciously inherited and reproduced generation after generation. What tensions lie beneath the structures of masculine control and power within my family? How do we read between the cracks of this trauma: of my mother and her mother before her? Of my father’s mother? How do we confront–and begin to weave–the unsaid, the suppressed, the broken, into emergent possibilities of being when so much of it preceded your own existence?

I began this project with a partial aim to come to terms with the roots of my story. I have found that I do not need to render things visible, nor do I want to. The blanks of the archives have opened a universe of possibilities to rethink my grandmas’ lives in terms of agency and identity and–in some ways– have liberated the work from the weight of uniquely playing witness, despite my continued desire to acknowledge my grandmas’s paths.

Allie Tsubota: Congratulations on this honorable mention! To begin, tell us about what brought you to photography. What drew you to the medium?

Elena Bulet i Llopis: Thank you so much! I arrived at photography through journalism, but I feel what made me commit to it for years were the answers that the medium gave me. Through photography I was able to express and convey feelings that I could not put into words. I found it to be a way of building close relationships with people and allowing me to belong somewhere or to something, even an idea. Which for me meant a lot because I have always been afraid of loneliness and of not belonging.

A.T.: And what about La balsa? How and when did you arrive at this project?

E.B.:In the past, I have always worked on stories related to identity with people who decided to trust me and collaborate together. We were trying to visualize certain parts of their lives or evoke certain feelings that they were marked by. When I knew I was starting this two-year journey, which is the MFA at Rhode Island School of Design, I felt I wanted to take the time to analyze my own story. I felt it was the right thing to do for me, going through this process, being on the other side of the camera, even if that will never make you fully understand the people you photographed, because there will always be a power relationship. At the same time, there were several things about my story that I was not fully aware of, or that I had not worked through as much as I would have liked.

It is interesting, because when I was a child, I was always anxious about revisiting the past. These anxieties became a paralyzing impasse that troubled me for years, but doing this project has been a way of circumventing it. La balsa is a Spanish word to describe a pond, a water storage for agricultural fields. I love the tone of voice that Elvira, one of my grandmas, has when pronouncing it. The pond near our family country house was also the space where several generations of my family swam together, but it does not exist anymore. I started the project by scanning both of my grandmother’s archives and looking for traces, hints, things that could explain parts of their lives, but also that could connect to mine.

A.T.: I’m struck by the different modes of picture-making you use in La balsa. The project recalls photographs as evidence (e.g., family archives) as well as photographs as sites of play and performance. Can you talk about your relationship to these two photographic temperaments? Do you see a relationship between the two as they are expressed in La balsa?

E.B.: I have been thinking a lot about how to incorporate the archives into the project and about the role I wanted them to have. There were some attempts before this one, where I was trying to intervene in the archive or collage the archive with my images. But none of them seemed to convey the feelings I was looking for.

I feel that the archives that are included have a sense of an evidentiary past, but at the same time, they convey some intimacy and mysteriousness because of the way the pictures are taken. I was really interested in the images that had those additional layers of meaning, because they allowed me to weave the past with contemporary photographs. Despite all of this, however, the project happens in a fictional terrain. The people in the archives become actors in the project. In the contemporary images, there are many recreations of memories, both mine and those of my relatives, which come together and culminate into a subjective truth.

A.T.: Many of the pictures in La balsa gesture toward bodies and their absence; they signal a type of haunting at the level of corporeality. I’m struck by these pictures, by their reference to histories of domestic and state violences, and by the way you’ve contextualized them within the language of “wounds,” “tensions,” “cracks” and “blanks.” Can you talk about the way you see bodies inhabiting La balsa? Human, non-human, ghostly or otherwise?

E.B.: The project includes a lot of gestures that aim for a return to childhood. This is a stage that marked me and left me with things I want to heal. But at the same time, it is a stage where innocence, imagination and play are also really present. The way Joanna Piotrowska approaches bodies, gestures and performance in her photography has been a big inspiration.

I feel the people who appear in the project are suspended in time, in an imaginary space, waiting for something to happen. This sense of waiting comes to fruition in another part of the project. Sometimes there are two people holding hands or flowers that come back in a slightly different way… I wanted to create a space for the viewer to imagine, to fill in the blanks, or to just exist in between marks. I also wanted to allow myself to invent possibilities and new beginnings for my grandmas’ lives. To visualize their complexity. This is something I have been discussing at length with Laine Rettmer and Zoé Samudzi, who recommended the essay “Venus in Two Acts” by Saidiya Hartman, which became a huge inspiration as well.

In this project, I also understand space as interior landscapes. And the objects that appear on them as actors with a role and feelings to convey. Even if they are not human, like the apples in the desert or the hay in the barn, they still activate the image and have a purpose in the story.

A.T.: I’m drawn to the levels of intimacy in La balsa–between you and your grandmothers, between a viewer and a subject, and between lived experience and the histories that support it. What role does intimacy play in this project, and in your practice more generally?

E.B.: It means a lot that you can see intimacy in the project, because that was one of my biggest goals. I do not feel comfortable explaining all the details of the story, I want to preserve a level of opacity. But I was hoping to develop a project in which people could feel intimate and vulnerable with the photographs and also with each other. I really liked the concept of public intimacies that Giuliana Bruno describes in Sites of Screening: Cinema, Museum and the Art of Projection.

I tend to think of my work according to the atmosphere it conveys all together in a space. Hopefully, it also brings closer the people viewing the work at the same time. It can be hard to share from this emotional space, because we have built boundaries to protect ourselves. But at the same time, I feel it is the space in which trust appears.

This intimacy has also been a way to feel close to my grandmas, especially to la abuela Mari, because she died when I was really young, so there has been a lot of looking for her in the project. Looking for evidence of our relationship, of the love she had for her granddaughters… The photographs then have this duality, a search for something, but then the whole project becomes a personal proof of it.

A.T.: La balsa spans distance, both in space and time. Can you talk about how you negotiate making work across geographic distance (between Spain and the U.S.) as well as how you approach the distance between history and the “now”?

E.B.: It has been a challenge to do this. In a way, sometimes it is easier to think about your own story when you are far from the place you were born. It allows you to take the space to conceptualize certain things. But at the same time, I feel the need to reevaluate and reassess upon returning home to Catalonia, because my feelings, perceptions and memories change every time this happens.

In terms of photography, it also has been a journey to negotiate distance. For many of the images, I do not see it as a problem because ultimately everything in the pictures is a recreation of a memory, but I did want to make portraits of my family and revisit some of the important places of our childhood with them, and waiting for that until it could happen was one of the hardest things. But I feel the images I made when we could do that sort of became the base of the project and its visual language.

An important source of the project are my relatives’ memories. They recall things that happened in the past, but from the “now”, which probably makes them slightly different from what really happened in the specific events. I wanted to embrace the subjectivity of memory and the modifications that our mind does into our lived experiences, because it can also be a way of healing specific situations.

A.T.:We met just before you entered the graduate program at RISD. How has being in a graduate program and community affected your practice and your approach to making photographs?

E.B.: It has been incredible. The conversations that we have been having in the program have completely shaped my practice. I became more aware of who I am and what I want to say with my photography. I feel really lucky to be able to participate in a space in which there are so many talented people willing to listen and engage with your practice. My cohort and the faculty of not only the photo department, but also of other areas of RISD have been really helpful in terms of guidance and mentorship.

A.T.: Are there any mentors, teachers or personal champions that you’d like to acknowledge?

E.B.: This is a hard one, because there are so many people who have influenced my practice… Some of them I have already mentioned before, like Zoé Samudzi and Laine Rettmer. And also conversations with Jocelyne Prince, Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, Karen Marshall, Brian Ulrich, John Willis and Steve Smith marked me a lot during these last years.

For La balsa, I have also been coming back to the work of Widline Cadet, Seremoni Disparisyon, and of Lebohang Kganye, Ke Lefa Laka. I really admire the level of intimacy and depth they are able to reach with their photography.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2023 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Tristan SheldonJuly 30th, 2023

-

The 2023 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Hannah NigroJuly 29th, 2023

-

The 2023 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Elena Bulet i LlopisJuly 28th, 2023

-

The 2023 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Paola ChapdelaineJuly 27th, 2023

-

The 2023 3rd Place Lenscratch Student Prize Winner: Anna RottyJuly 26th, 2023