The 2023 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Hannah Nigro

It is with pleasure that the jurors announce the 2023 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner, Hannah Nigro was selected for her project, Office Files Not to be Taken Away, and is currently pursuing an M.F.A. at the Rhode Island School of Design. The Honorable Mention Winner receives: $250 Cash Award and a Lenscratch t-shirt and tote.

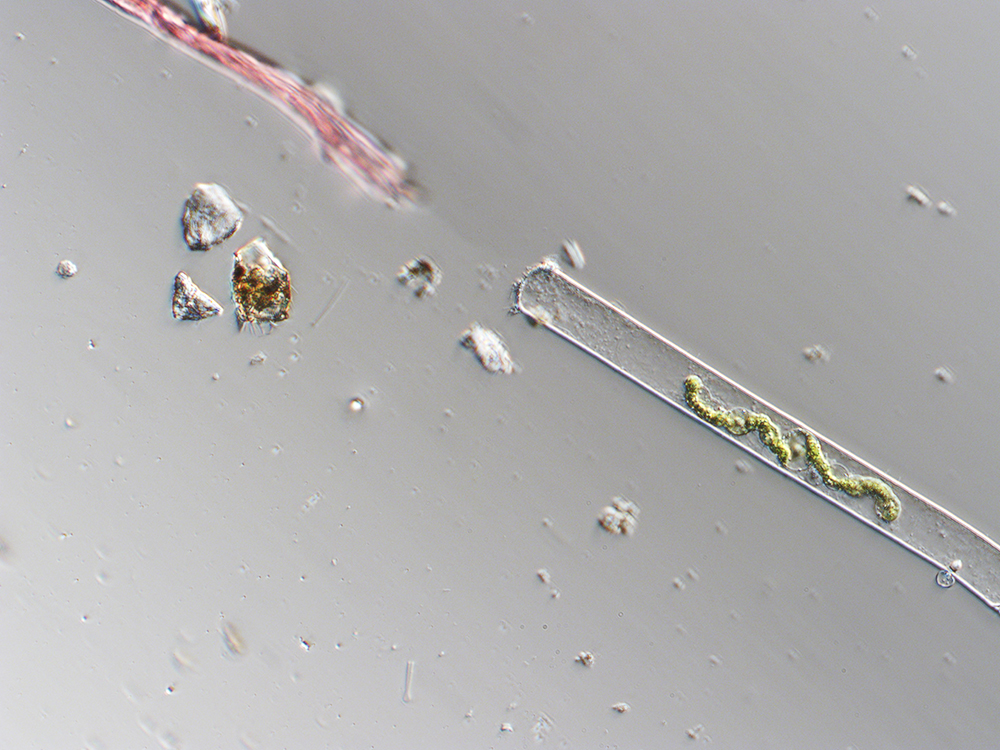

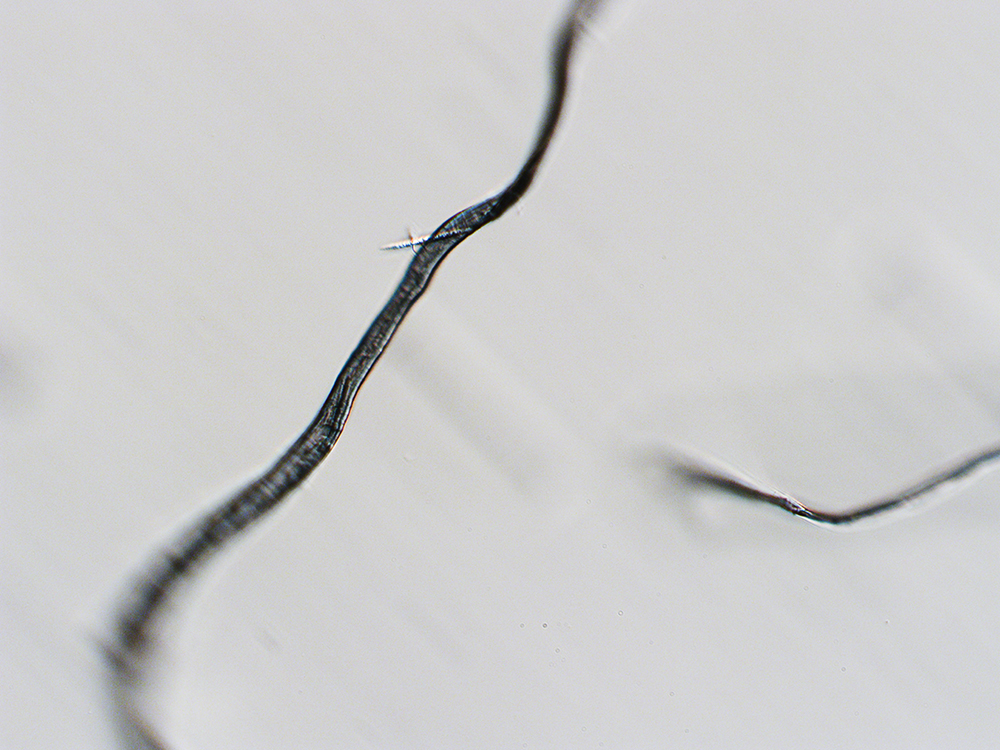

The water up here flows like a tide back and forth through time, but ultimately it always moves in one direction: to the city. It flows through the intentionally breached dam, flooding the new reservoir in 1915. It flows even today, through tunnels and aqueducts and more reservoirs and pipes and faucets, landing in your cup in New York City as liquid magic. Hannah Nigro takes the magic of water, with its powers of life and death, as her subject in her ongoing project, Office Files Not to Be Taken Away. Through absolutely gorgeous photography, cartography, microscopy, archival imagery, and soundscapes, Nigro explores the City’s water supply and the historical complexities of its creation. Magic here can leave a strange taste in one’s mouth.

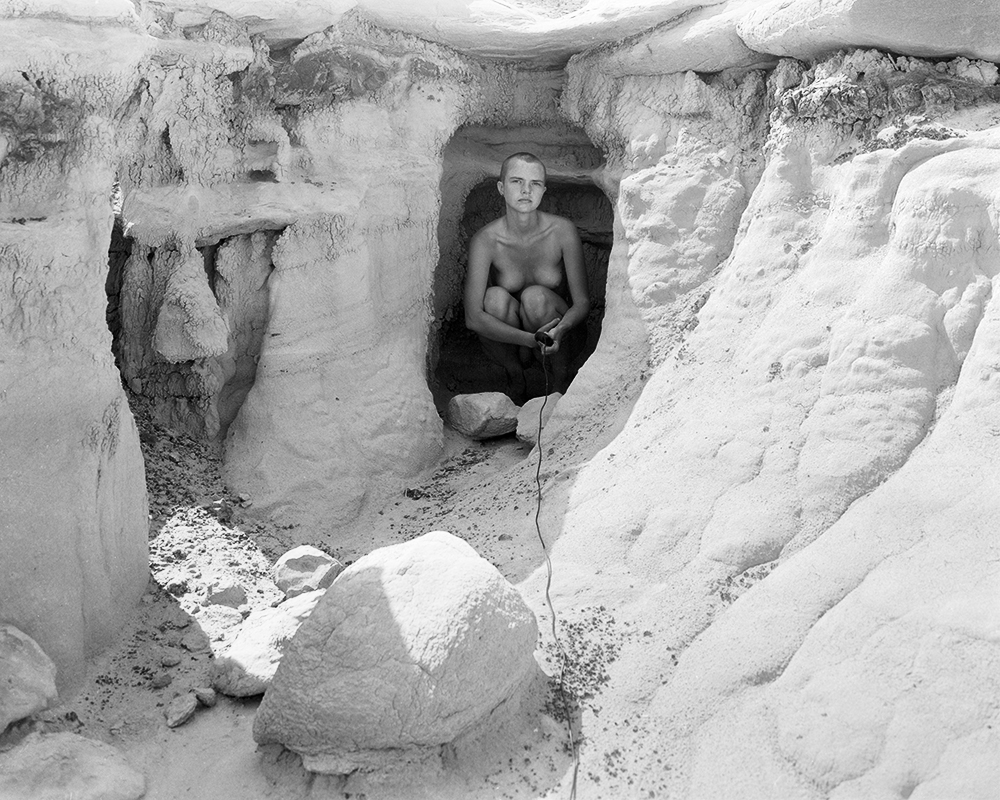

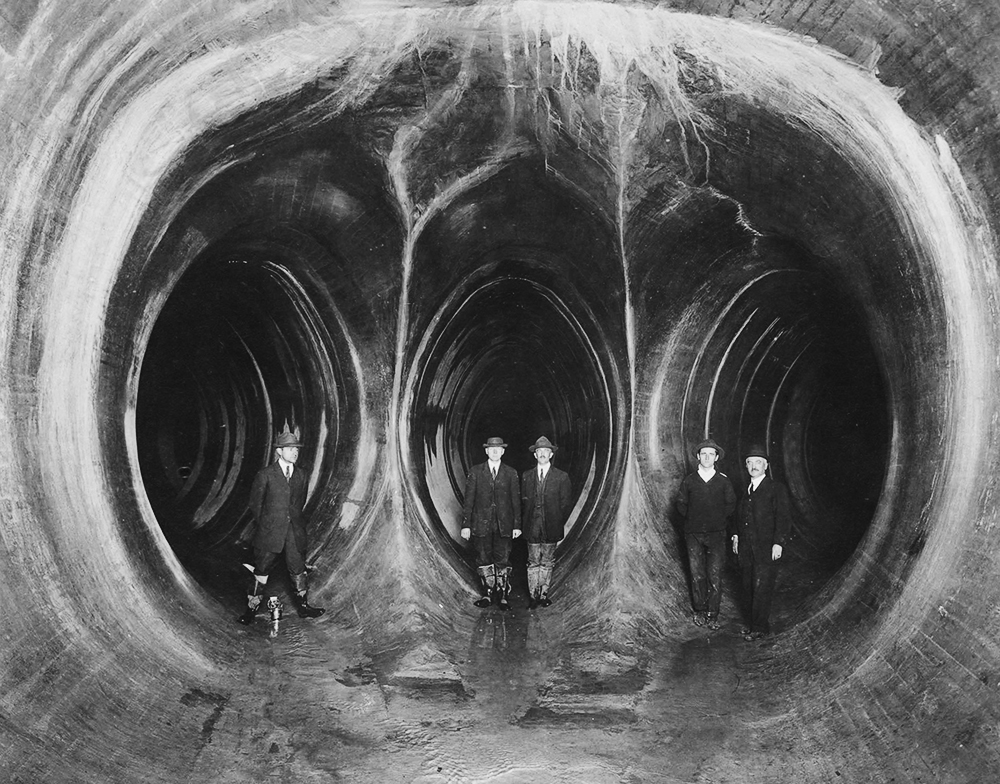

Hannah has done the dirty work of photography projects, getting into the woods and concrete structures that make up New York’s upstate reservoir system. Her contemporary images are full of texture, of mud, of flooded waters and lichen, that I cannot help but feel I am part of the reservoir. But it is when these contemporary images interact with photographs sourced from the archives that this project begins to take off. The building of the water system yielded stunning pictures of the hidden infrastructure beneath our feet. It is a triumph of Nigro’s own photography and skillful sequencing that such spectacular archival images do not overwhelm the project; instead they sit as silent witnesses to a nuanced past.

The history of these reservoirs is no walk in the park. Hundreds of buildings and residents, whole towns with churches, cemeteries, drug stores, and railroads were removed to make way for these vast bodies of water. Can one imagine watching their whole world, past and present, picked up and carted up the road? Can one imagine having to leave it behind to be flooded? Yet I confess I am torn by this history. The water of the reservoirs creates life just as easily as it destroys it. Can one imagine all of the raw humanity that has derived from it? Can one imagine a world without it?

Office Files Not to Be Taken Away stands out as a richly researched and thought out body of work. It grapples deeply with the complexities I have laid out, never shying away from humanity’s penchant for violently reshaping the land, towns and all, to suit our needs. But, as Nigro points out, there is something to, “The irony of their [ the town’s] destruction as a simultaneous act of preservation.” There are stories buried beneath the water here. Stories that Hannah Nigro continues to sift through with her camera.

An enormous thank you to our jurors: Aline Smithson, Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Daniel George, Submissions Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Linda Alterwitz, Art + Science Editor of Lenscratch and Artist, Kellye Eisworth, Managing Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Alexa Dilworth, publishing director, senior editor, and awards director at the Center for Documentary Studies (CDS) at Duke University, Kris Graves, Director of Kris Graves Projects, photographer and publisher based in New York and London, Elizabeth Cheng Krist, Former Senior Photo Editor with National Geographic magazine and founding member of the Visual Thinking Collective, Hamidah Glasgow, Director of the Center for Fine Art Photography, Fort Collins, CO, Yorgos Efthymiadis, Artist and Founder of the Curated Fridge, Drew Leventhal, Artist and Publisher, winner of the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize, Allie Tsubota, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2021 Lenscratch Student Prize, Raymond Thompson, Jr., Artist and Educator, winner of the 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize, Guanyu Xu, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2019 Lenscratch Student Prize, Shawn Bush, Artist, Educator, and Publisher, winner of the 2017 Lenscratch Student Prize.

An enormous thank you to our jurors: Aline Smithson, Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Daniel George, Submissions Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Linda Alterwitz, Art + Science Editor of Lenscratch and Artist, Kellye Eisworth, Managing Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist, Alexa Dilworth, publishing director, senior editor, and awards director at the Center for Documentary Studies (CDS) at Duke University, Kris Graves, Director of Kris Graves Projects, photographer and publisher based in New York and London, Elizabeth Cheng Krist, Former Senior Photo Editor with National Geographic magazine and founding member of the Visual Thinking Collective, Hamidah Glasgow, Director of the Center for Fine Art Photography, Fort Collins, CO, Yorgos Efthymiadis, Artist and Founder of the Curated Fridge, Drew Leventhal, Artist and Publisher, winner of the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize, Allie Tsubota, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2021 Lenscratch Student Prize, Raymond Thompson, Jr., Artist and Educator, winner of the 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize, Guanyu Xu, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2019 Lenscratch Student Prize, Shawn Bush, Artist, Educator, and Publisher, winner of the 2017 Lenscratch Student Prize.

Hannah Nigro (b. 1997, Minnesota) is an image-based artist dedicating her practice to chipping away at anthropocentrism. She is based in the Northeast United States, primarily splitting time between the ancestral lands of the Narragansett, Wampanoag and the Haudenosaunee peoples. Seeking to encourage the viewer to consider a larger scope of temporality beyond the anthropocene, she hopes to reveal the magical uncanniness of macro geological shifts that have enabled human micro existences. A fascination with the fossilisation of lived experiences over deep time grounds her art making. Her works have been exhibited throughout the Northeast. She is a current candidate for a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Photography from the Rhode Island School of Design, where she received the Harry Koorejian Memorial Scholarship. She is a big fan of : her part-feline part-gossip columnist cat Spike, Whale sharks, and her 8 year old green Nalgene (not sponsored). She dislikes private property and cilantro.

Instagram: @hannahnigro

“And in a single day and night of misfortune all your warlike men in a body sank into the earth, and the island of Atlantis in like manner disappeared in the depths of the sea.” —Timaeus

Office Files Not to Be Taken Away

In Italo Calvino’s “Invisible Cities,” the narrator poetically constructs cities for Ghengis Khan, who has asked him to discover the world. The city of Baucis swims in the clouds and Raissa’s inhabitants live two lives, at once unhappy and happy. At the end, the narrator reveals that he has only ever been describing one city : Venice. What if this city was Atlantis? Plato’s “Critias” tells of Atlantis, an island allotted to Poseidon, sunk by an earthquake after a failed battle with Athens. These folktales materialized for me out of the submerged towns of the Catskills that have been lost to water and time. Both Atlantis and the Catskills bear likeness in their pre-sunken states: rich in fertile soil and abound with flowing water. Just as “Critias” ends abruptly, leaving the history of Atlantis unknown, the continued lives of the sunken Catskill towns go untold. This project proposes to capture, dredge, and reconstruct the lives and structures of the very real, abandoned cities sapped and sacrificed for the good of the New York City metropolis.

In 1905 the New York State Legislature passed the McLellan Act, beginning the city’s long-lived campaign to obtain populated rural lands for use in an ongoing project to supply New York City’s increasing population with adequate water. The project was to be realized through the creation of a complex network of reservoirs and aqueducts which would alter and destroy the natural ecological landscape of the Hudson Valley. Within 10 days of an appraisal commission’s appointment, villages could be condemned and purchased for a fraction of their worth. Infrastructure would then be set ablaze, and submerged in water meant to be funneled south to the island of Manhattan. Valley lore claims that when the reservoirs’ levels drop low enough, remnants of homes peak through the water’s surface.

The conceptual draw of these water-logged hamlets is the irony of their destruction as a simultaneous act of preservation. Today the structures of these submerged towns survive as magical, subaquatic metropolises. The Catskills cradle the fantastical worlds of Ashokan, Neversink, Olive and twenty-three other towns which were glazed in a liquid encasing of time. Underwater ghosts continue familiar patterns of life – navigating bartering economies, preserving familial relationships rooted in land tilling, making yearly trips to the big town of Kingston. The once spiritual connection between the living and the land is marred by the state’s unforgiving history of exploitative use. How have such decisions that support production over sustainable stewardship rerouted lives and informed the current climate crisis?

My project deals with a living archive. While the majority of documentation is located in the early twentieth century when the project was first conceived of and realized, building continues today. Tunnel 3, a 60-mile-long water supply route, was only completed in 2021, acting as a third connection between Manhattan and the Upstate reservoirs. I am at once sifting through images from the fateful 1907 construction of the Catskill Aqueduct, and speculating about a future in which New York City’s water needs go unmet. I am fascinated by the events of forced land dislocation, motivated by capitalist priorities that at their core, further divide the “rural” and the “metropolis.” Destructive rumbles traced to over a century ago, still run through veins of the state’s topography. I’m interested in how this infrastructure decision and turning point served as a catalyst and foundation for land indifference.These images look to inform a narrative of upheaval and exploitation, tease out our complex relationships to the horrific yet enchanting ramifications of an engineered topography, and illustrate the disastrous decoupling of the environment and humankind — a cleavage that continues to affect our present, urgent realities.

With the funds awarded through this prize, I would return to Upstate New York to continue unearthing this project. This work has recently been presented as a solo exhibition as part of my thesis degree project, but there is so much more to do. With a contact I have who works for NYC Water, I hope to investigate the aqueducts in New York City. I would also like to collaborate with the present villages’ public libraries, to track down descendants of those affected by the enforced relocations. I would like to create a sound piece that strings together lively stories with cold legislative pieces. I also look forward to creating photographic prints combined with concrete, and pierced by rebar — two essential material components of the water system’s construction. Through purchases of film, materials, printing,ad travel expenses, the funds awarded by Lenscratch would enable me to develop this project further.

Drew Leventhal: Hey Hannah, congrats on being a Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention! Your project Office Files Not to be Taken Away seems very geographically rooted in the Hudson Valley and the Ashokan Reservoir. Can you talk a little about your interest in that region? Do you see the specific geography as important or can the pictures spread out and flow like so much water?

Hannah Nigro: I was spending a lot of time in the Catskills due to my partner at the time living there. I had already been spending time in a mine nearby where limestone was extracted for cement production for New York City building projects. After reading further into the history of the area, I remember coming across a local myth disguised as fact that when the reservoirs are low enough house foundations from towns eradicated by the reservoirs would peek through. Though I later discovered this to be untrue, I was gripped by the image of a submerged town that sometimes revealed itself to the terrestrial world.

I decided to spend that summer before my senior year living in the town of Catskill to root myself in the area and work further on this project that I knew would be my degree thesis. The more I researched the more apparent it became that these rich rural lands of the Hudson Valley were reduced to excavation sites for the benefit of furthering the progress of New York City. That history merged with the present as I bore witness to the migration of urbanites to the region that occurred during the pandemic and the resulting property increases and gentrification attached to that. This is all to say I was deeply fascinated by what I perceived to be a very one-sided, parasitic relationship between New York City and Upstate.

This project deals with themes that expand outside of the geography of the Hudson Valley, though New York City and this engineering project are important signifiers because of their megalithic nature. The relocating and destroying of towns for water infrastructure is not unique to this area; the Quabban Reservoir in my home state of Massachusetts has a similar history. So to that end, I think this project can point to multiple histories at once.

DL: One thing that really stood out to me is your use of the archive. There are some phenomenal images you pulled from the past. How has your relationship to these archival images changed as your project has developed?

HN: Funnily enough, I had the image of the three men in suits in the aqueduct on my computer long before this project took place. I sometimes scroll through the New York Public Library archives out of interest and that image immediately gripped me. It’s uncanny and bizarre, and for a long time I was drawn to it without ever knowing the history behind it. I was shocked to see it again in a book I was reading about the history of New York’s water supply. Like that image, much of the archive stands on its own, shots that seem unbelievable today but that represent sentiments still present. There’s one image of the engineers seated together for a celebratory feast…within the cold uniformity of the aqueduct and beneath a large American flag.

A lot of the images served as support for the research I was doing, powerfully manifesting the ideas contained in the written language.

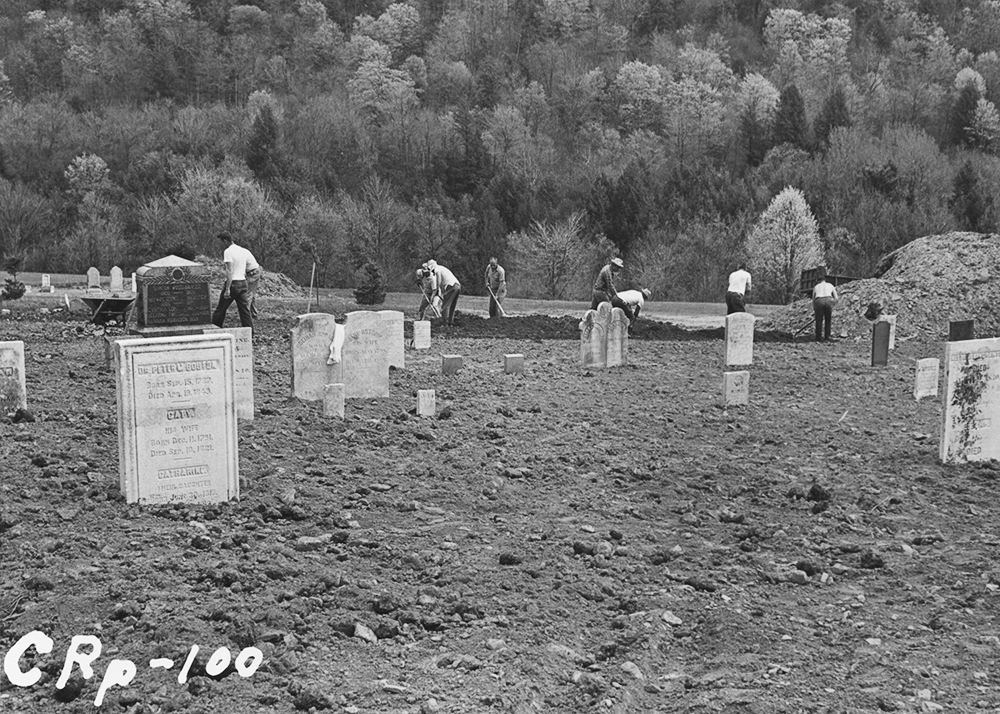

Many of my own images were shot without thinking of any specific archival imagery, but more so thinking about the ideas of power and ecological subjugation that are a through current in the archives. However, eventually I believe imagery from the past started to creep into my subconscious — I think of the image of Harper’s body strewn across the reservoir’s steps. To me, that image can not be separated from one of the men digging up bodies from the cemetery for relocation. So as time goes on, I think the archive dictates some of the images I am making, to further comment on the historical attitudes about land and community that continue into the modern day.

D.L.: In your statement you make a beautiful connection between Venice/Atlantis and the submerged towns that have been entombed by New York’s reservoirs. The complexity of water plays the central role in the story you are telling. Can you draw that connection out for me more? Does this body of work see water as life giving/sustaining or as a destructive force?

H.N.: As I mentioned earlier, the myth of a revealed house foundation immediately harkened back to Atlantis for me, of lives and towns continuing beneath the waters. As a child I ravenously consumed fantasy books, and I still maintain that attraction to the magical.

Water has always been super important in my life — growing up in a coastal state and being a stone’s throw away from the ocean, water has always been at the forefront of my mind and is super important to my being. I can never stray too far from the ocean without feeling unbalanced. I do think that there is this duality that you’ve mentioned where water is kind of the most essential element there is for human survival and at the same time it has this destructive nature. It has the power to destroy communities and also reshape landscapes and erode and make these great changes. In my opinion, the great issue facing us in our lifetime will be access to clean water. But we must be careful how we create clean water. As I just said, water has this incredible power and I think the lack of acknowledgement of this power, the desire to dominate and conquer forces beyond our control, has been man’s greatest folly. That attitude is ultimately why we have arrived at the climate crisis we are facing today, that specific desire to dominate. That’s what I was trying to draw out in the archive; traces of this vain attitude — of the men in their suits smiling with such pride for an engineering feat that is, ultimately, a feat of recarving the land: dictating how it moves, how water flows, how we harness its power to enable the existence of the metropolis. That pride has always been so naive to me, to not think about the consequences in intervening with ecology.

I just love water, that raw power against the beautiful ability to cleanse and rebirth and regenerate. There are elements of water that I try to emulate in my photography — the smooth, curving lines that occur in my more fantastical or magical attempts at photography. These directly contrast the imagery with harsh lighting jagged lines that I think speaks to more of a disregard for water and its power.

D.L.: Lastly, I am excited to hear about how you want to continue developing this project, it seems that there is so much to explore!

H.N.: This is one of those forever projects for me I think. I’m super excited to see where it goes. While I was grappling with it at school I was at times so overwhelmed because even the duality in myself of being drawn to the fantasy element of it, of these constructed Atlantis-like images in my head versus the rough and violent destruction that is the reality of this engineering project, and even grappling with how to balance that duality. These are really complicated feelings that I am excited to keep working on down the road!

©Hannah Nigro, Disinterment of deceased from cemeteries and burying grounds in the reservoir area and reinterment at Pepacton Cemetery. Placing memorials and concrete markers at graves, and resurfacing the cemetery by placing topsoil, seed and fertilizer. Work done by Board’s force. Camera located in roadway, 15′ south of Section 43, looking Southeasterly. View shows the Board’s force spreading material which was moved from the storage pile at upper right corner and dumped at Section 75 and 76. In the foreground is seen material which has been spread and graded, but not raked. The memorial to Dr. Peter W. Bouton and family, embedded in a concrete base (which has been covered) is seen in the left foreground.

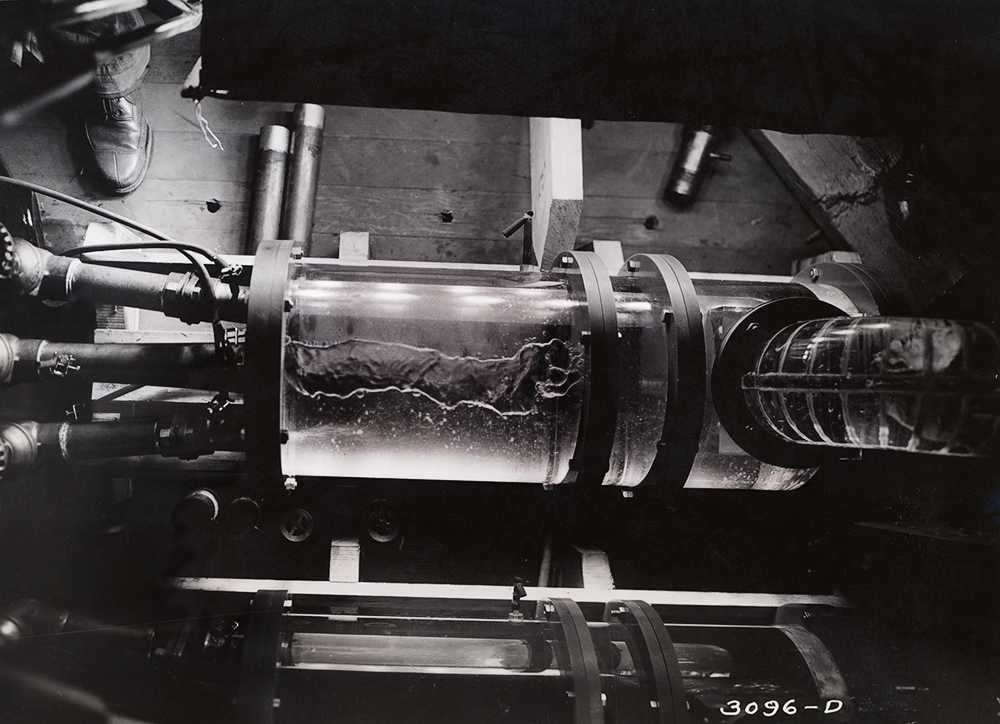

©Hannah Nigro, Rondout Reservoir. Delaware Aqueduct. Construction of Merriman Dam and portion of Rondout-West Branch Tunnel. Contract 340. Mason and Hanger Company, Incorporated, contractor. Model tests of Rondout Effluent Works. Tests at pumping station of Department of Water Supply, Gas and Electricity, Grant City, Staten Island. For description of Rondout Effluent Works, models and tests, see issues number 48, 73, and 74 of The Delaware Water Supply News, pages 202, 333 and 341. 1940.

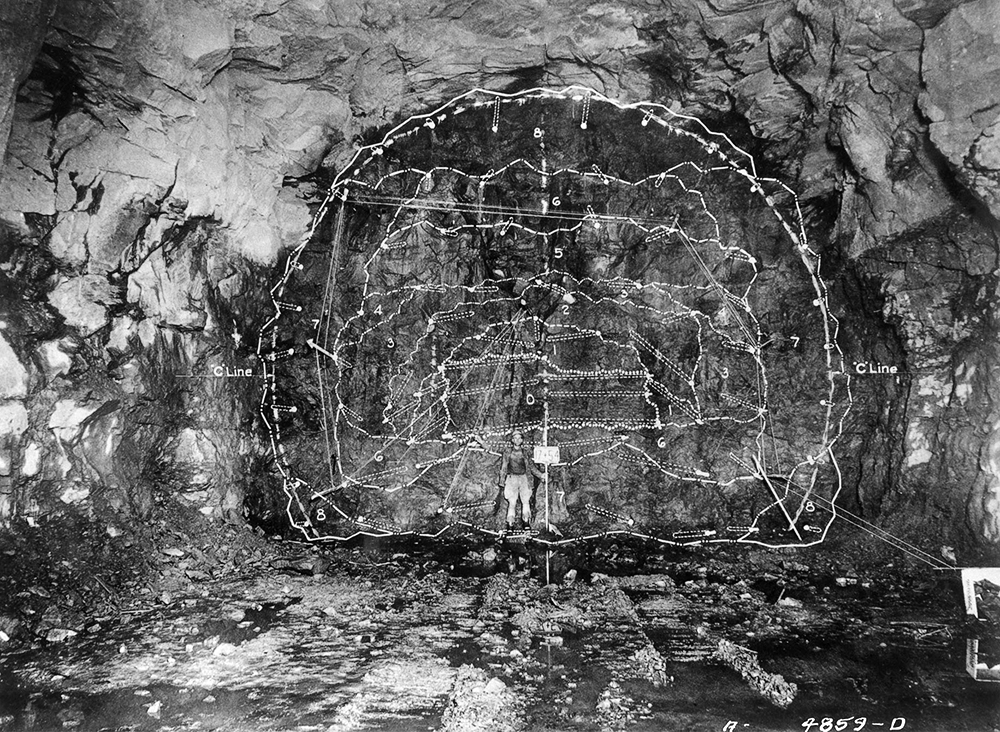

©Hannah Nigro, Neversink Reservoir. Neversink Dam. Neversink Division. Construction of coffer-dam and diversion tunnel and sinking of exploratory caissons. Contract 360. George M. Brewster and Son, Incorporated, contractor. Diversion tunnel south heading. Camera located on center line of diversion tunnel at Station 18+00 looking north. View showing heading, Station 17+54, with actual positioning and angling of its 68 drill holes. There were 6 cut holes 16 feet deep and 62 14-foot holes comprising first and second relievers, breakdown, lifters and line holes. Heading as loaded: 68 primers 1.25 inches by 8 inches at .40 pound, 40 percent gelatin; 1,240 plain sticks 1.5 inches by 8 inches at .56 pound, 40 percent gelatin. There are superimposed upon the photograph white lines diagrammatic of the break areas for the numbered delays. Drilling lies within the “C line” for full faced horseshoe shaped section averaging 26 yards to the foot, the bottom being 10+/- feet above finished invert. February 27, 1942.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2023 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Tristan SheldonJuly 30th, 2023

-

The 2023 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Hannah NigroJuly 29th, 2023

-

The 2023 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Elena Bulet i LlopisJuly 28th, 2023

-

The 2023 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention Winner: Paola ChapdelaineJuly 27th, 2023

-

The 2023 3rd Place Lenscratch Student Prize Winner: Anna RottyJuly 26th, 2023