The CENTER Awards: Excellence in Multimedia Award 1st Place Winner: Leonard Suryajaya

Congratulations to Leonard Suryajaya, for his First Place win in CENTER’S Excellence in Multimedia Award for her project, False Idol. The Excellence in Multimedia Award recognizes outstanding photo-media artists and storytellers working in a variety of media processes and subject matter. Supports a project that utilizes photography, video, installation, or other elements that expand on traditional methods of displaying and experiencing photography. Winners receive an opportunity to be part of the Winners Exhibition at El Museo Cultural de Santa Fe, complimentary participation and presentation at Review Santa Fe for the 1st place winner in each category, and an Online exhibition at VisitCenter.org

Juror Carrie Levy – Creative Director, The New York Times shares her insights:

As technology evolves so does the definition of multimedia art. However, it’s not the tools that make lasting art, it is how the artist uses these tools to express experiences and ideas. Reviewing the work for the CENTER Multimedia Award has been both creatively challenging and enlightening. Today people are not only being creative with media processes, they are reinventing new ways to share and tell facts and stories. The work that caught my attention are artists who are pushing multimedia forward in unexpected and imaginative ways, and at the same time touching pressing issues that both define and divide us.

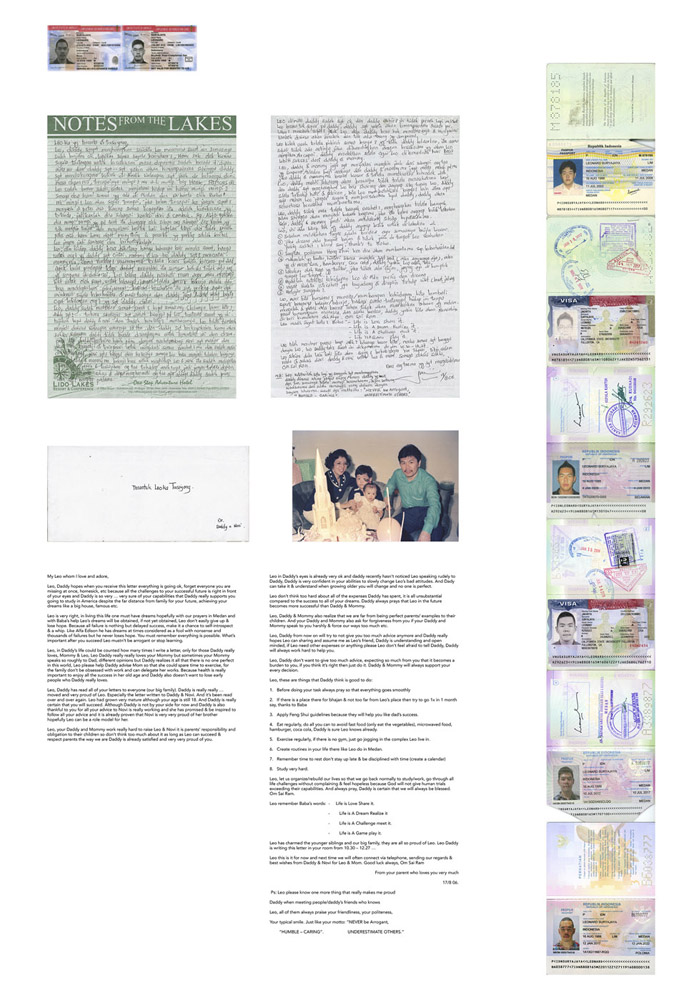

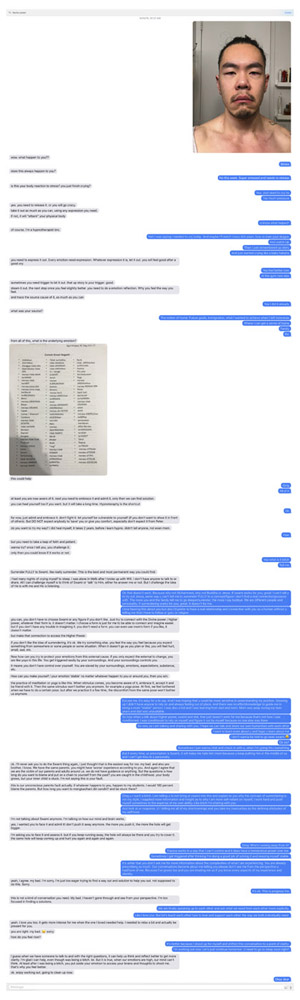

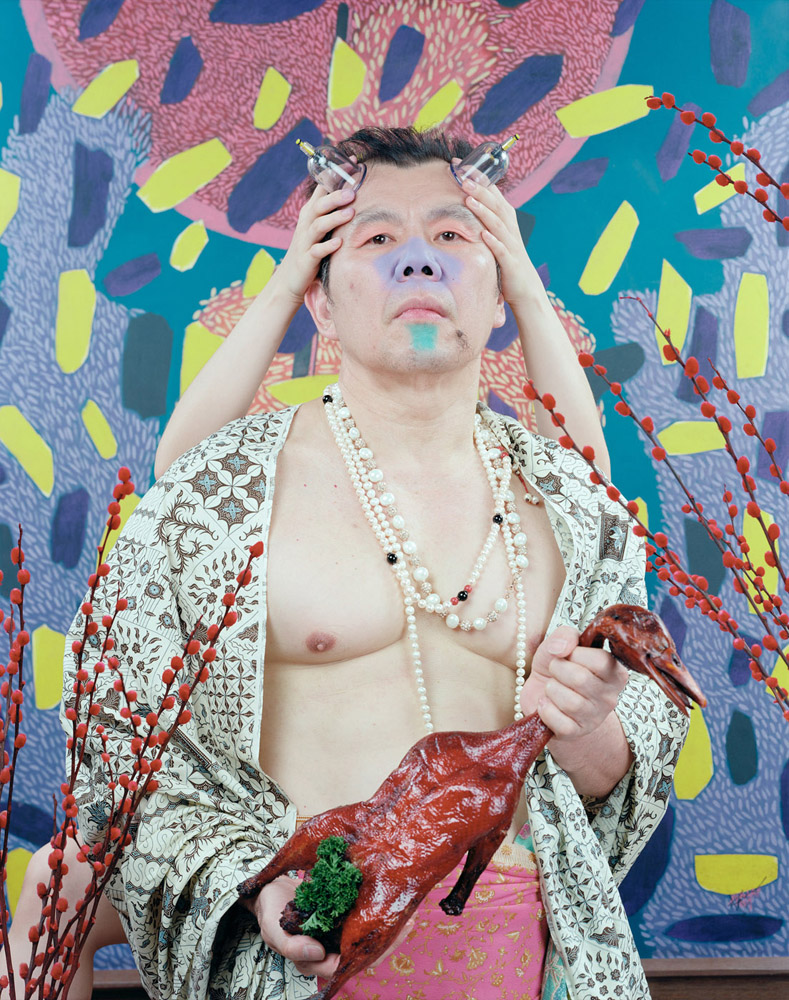

Leonard Suryajaya’s series False Idols pushes the boundaries of representation of his/our intimate relationships. Using his loved ones as subjects in his bizarre play, Suryajaya creates elaborate scenes that are beautiful, absurd and at times disturbing. He works with several different mediums to stretch our point of view on immigration and culture norms. Suryajaya’s collages are immediately curious and unusual, yet at the same time highlight a tenderness that is very familiar. Along with photographs and video, Suryajaya also uses text as part of his imagery, words appear handwritten in installations, prints are created from his text chains, or emails superimposed into his images. The mix of words and images create an elaborate stage for multi-generational and racially diverse cast who perform his unique visual language. In the end, his work highlights that being different comes at an awkward emotional cost even though it’s something we all understand.

Carrie Levy started her career as a photographer and photo editor. Today she is a Creative Director who concentrates on experiences and storytelling with emerging technology tools. Carrie has worked as a creative lead at Airbnb, Instagram, and Apple. She has worked at various prestigious publications including Wired, GQ, Newsweek, The Wall Street Journal and more.

False Idol

Play, Mess, and imagination all touch within the frames of Leonard Suryajaya. There are exquisite disruptions of patterns and people. fingertips buzzing, the colorful leaves of plastics and fruits, and mouths almost always stuffed with something extraterrestrial. Suryajaya photographs, films, and makes art of something equally unexpected, as it is familiar and ancestral. False Idol explores themes of camaraderie and theatre, fleeing a homeland and putting down roots. A Chinese-Indonesian immigrant, Suryajaya is ready for powers and authorities that want to question the legitimacy of his every last morsel. “I’m going to make this work over the course of my Green Card application. I want to use this body of work as a way to document, reimagine, and expose that process”.

Suryajaya is possessed by navigating respect with pushiness. The rules of government and patriarchy are in place to watch and pry; the works of False Idol fight back with astute dexterity. Why simplify anything? In these works there is bargaining and resilience. The world that lurks inside Suryajaya’s frames seems both informed by an established visual history as much as it seeks to find a new place in the future on a planet not too dissimilar from this one. Or perhaps that place is still Earth, one where limitations have been outsmarted. Where the bizarre, unexpected, and queer can co-mingle and couple.

Suryajaya stands in the middle of streets, collecting, gathering, thinking, and finding all these simple things so they can be exposed for how outlandish they are capable of being. Our world no longer has to be what we’ve come to expect of its we’re better than that, this world deserves better than us if we can’t push ourselves towards the discovery that combining opposites will empower us. Our trauma is real and will make things difficult. We will either be for one another or we will be against one another. Suryajaya offers us this confusion as a tool to see possibility.

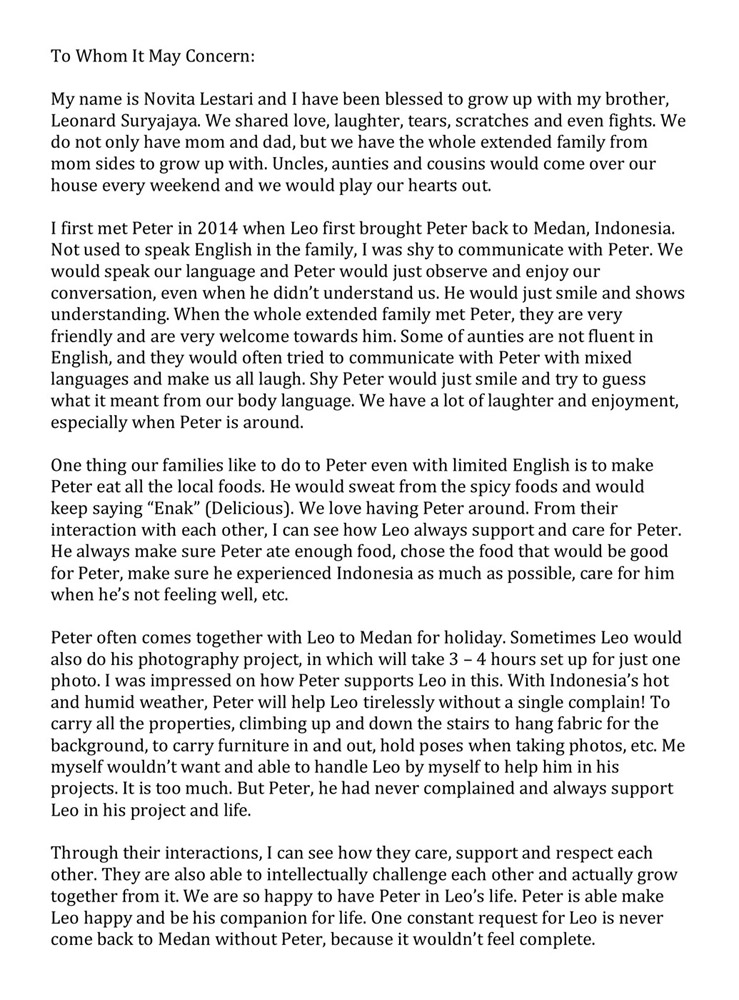

Leonard Suryajaya uses photography to test the boundaries of intimacy, community, and family. His works show how the everyday is layered with histories, meanings, and potential. In elaborately staged photographs bursting with competing patterns and colors, Leonard creates absurd but affectionate tableaux featuring his family. Enlisting his loved ones into his photographic project, he encourages ever more wild combinations and poses as means for them to perform their loyalty. The results are photographs that are tender and critical, bound up as they are with the struggles of familial authority and self identity. He has recently extended this in his work with school children and the complex but fragile societies they form among themselves and in relation to cultural forces both popular and traditional, local and global.

Many of Leonard’s investigations are rooted in the particularity of his upbringing as an Indonesian citizen of Chinese descent, as a Buddhist educated in Christian schools in a Muslim-majority country, and as someone who departed from his family and his culture’s definitions of love and family. Leonard explores these tensions in the everyday interaction, in the chance juxtaposition of culturally-coded objects, and in the disruptions stirred by queer relations. His works perform the ways in which life is soaked not just with one’s own emotional connections but larger, external histories of exile, religion, citizenship, duty, and belonging. His photographs work cumulatively to establish narratives, and he combines these images with videos that document family histories, that play out fantasies, that test group dynamics, or that use the format of the interview to turn his sitters’ gaze back upon his role as artist and facilitator. In all of these, we feel the push and pull of allegiance and autonomy in every odd detail that his works retain as reminders.

Mom in Chicago from Leonard Suryajaya on Vimeo.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)October 1st, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: George Nobechi (2021) and Ingrid Weyland (2022)September 30th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Amy Friend (2019) and Andrew Feiler (2020)September 29th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Jennifer McClure (2017) and JP Terlizzi (2018)September 28th, 2025

![In the early morning of Sunday, September 15, 1963, four members of the United Klans of AmericaÑThomas Edwin Blanton Jr.,Herman Frank Cash, Robert Edward Chambliss, and Bobby Frank CherryÑplanted a minimum of 15 sticks of dynamite with a time delay under the steps of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, close to the basement.

At approximately 10:22 a.m., an anonymous man phoned the 16th Street Baptist Church. The call was answered by the acting Sunday School secretary: a 14-year-old girl named Carolyn Maull. To Maull, the anonymous caller simply said the words, "Three minutes", before terminating the call. Less than one minute later, the bomb exploded as five children were present within the basement assembly, changing into their choir robes in preparation for a sermon entitled "A Love That Forgives". According to one survivor, the explosion shook the entire building and propelled the girls' bodies through the air "like rag dolls".

The explosion blew a hole measuring seven feet in diameter in the church's rear wall, and a crater five feet wide and two feet deep in the ladies' basement lounge, destroying the rear steps to the church and blowing one passing motorist out of his car. Several other cars parked near the site of the blast were destroyed, and windows of properties located more than two blocks from the church were also damaged. All but one of the church's stained-glass windows were destroyed in the explosion. The sole stained-glass window largely undamaged in the explosion depicted Christ leading a group of young children.

Hundreds of individuals, some of them lightly wounded, converged on the church to search the debris for survivors as police erected barricades around the church and several outraged men scuffled with police. An estimated 2,000 black people, many of them hysterical, converged on the scene in the hours following the explosion as the church's pastor, the Reverend John Cross Jr., attempted to placate the crowd by loudly reciting the 23rd Psalm through a bullhorn. One individual who converged on the scene to help search for survivors, Charles Vann, later recollected that he had observed a solitary white man whom he recognized as Robert Edward Chambliss (a known member of the Ku Klux Klan) standing alone and motionless at a barricade. According to Vann's later testimony, Chambliss was standing "looking down toward the church, like a firebug watching his fire".

Four girls, Addie Mae Collins (age 14, born April 18, 1949), Carol Denise McNair (age 11, born November 17, 1951), Carole Robertson (age 14, born April 24, 1949), and Cynthia Wesley (age 14, born April 30, 1949), were killed in the attack. The explosion was so intense that one of the girls' bodies was decapitated and so badly mutilated in the explosion that her body could only be identified through her clothing and a ring, whereas another victim had been killed by a piece of mortar embedded in her skull. The then-pastor of the church, the Reverend John Cross, would recollect in 2001 that the girls' bodies were found "stacked on top of each other, clung together". All four girls were pronounced dead on arrival at the Hillman Emergency Clinic.

More than 20 additional people were injured in the explosion, one of whom was Addie Mae's younger sister, 12-year-old Sarah Collins, who had 21 pieces of glass embedded in her face and was blinded in one eye. In her later recollections of the bombing, Collins would recall that in the moments immediately before the explosion, she had observed her sister, Addie, tying her dress sash.[33] Another sister of Addie Mae Collins, 16-year-old Junie Collins, would later recall that shortly before the explosion, she had been sitting in the basement of the church reading the Bible and had observed Addie Mae Collins tying the dress sash of Carol Denise McNair before she had herself returned upstairs to the ground floor of the church.](http://lenscratch.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/001-16th-Street-Baptist-Church-Easter-v2-14x14-150x150.jpg)