2025 PPA Photo Award Winner: Teela Misa DeLeón

Pasadena Photography Arts is thrilled to announce that the PPA Photo Award 2025 has been granted to Teela Misa DeLeón for their project, “Multivalent.” This year’s PPA Photo Award was an open call for “Excellence in Contemporary Photography” accepting projects from emerging and professional photographers around the United States. This award is dedicated to projects that have had limited or no prior public exposure or publication. We are proud to offer this annual award that gives a platform to voices and visions that deserve to be seen and heard.

Teela Misa DeLeón’s award winning project is featured below alongside an exclusive interview with guest juror Eve Schillo, Associate Curator of the Wallis Annenberg Photography Dept., Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA).

Join Pasadena Photography Arts on Wednesday, October 8th at 5:30pm PDT for a VIRTUAL artist talk where Teela will share their creative journey and story behind their winning project! Sign up here for FORUM: An Artist Talk with PPA Photo Award Winner Teela Misa DeLeón

Teela Misa DeLeón is an interdisciplinary artist and writer working primarily with experimental large-format photography and alternative process printmaking to explore perception, relationality, and transformation.

Rooted in patient and process-driven approaches, their work engages with in-between spaces— between document and dream, presence and absence, between what is seen and what resists visibility.

Through an integration of tactile making and conceptual inquiry, their practice traces intimate and historical intersections—where collective memory meets the emotional and material realities of bodies, identities, and our relationship to images. These images offer slow and intentional encounters—sites for intuitive sensing and reflection on a poetics of visibility and the subtle rituals of seeing embedded in everyday life that shape meaning.

DeLeón is based in Olympia, Washington, on the traditional unceded land of the Coast Salish peoples. Their work has been exhibited throughout the Pacific Northwest and United States, including venues such as Photographic Center Northwest, Verum Ultimum Art Gallery, and Plaxall Gallery. DeLeón studied Gender and Sexuality, Critical Theory, Psychology, and Visual Arts at UC Santa Cruz and Evergreen State College, and is currently pursuing an MFA in Photography at the Savannah College of Art and Design.

Recent bodies of work include Object Permanence, documenting queer and trans life through sentimental objects; Bind/Unbound/Bind, investigating relational perception through material rupture; and Legible Silences, exploring silence as presence rather than absence.

INSTAGRAM: @havenever.ever

My work explores how meaning resists containment—how perception, memory, and identity are layered, fragmented, and continually remade. Images can reflect things we can’t fully see or explain.

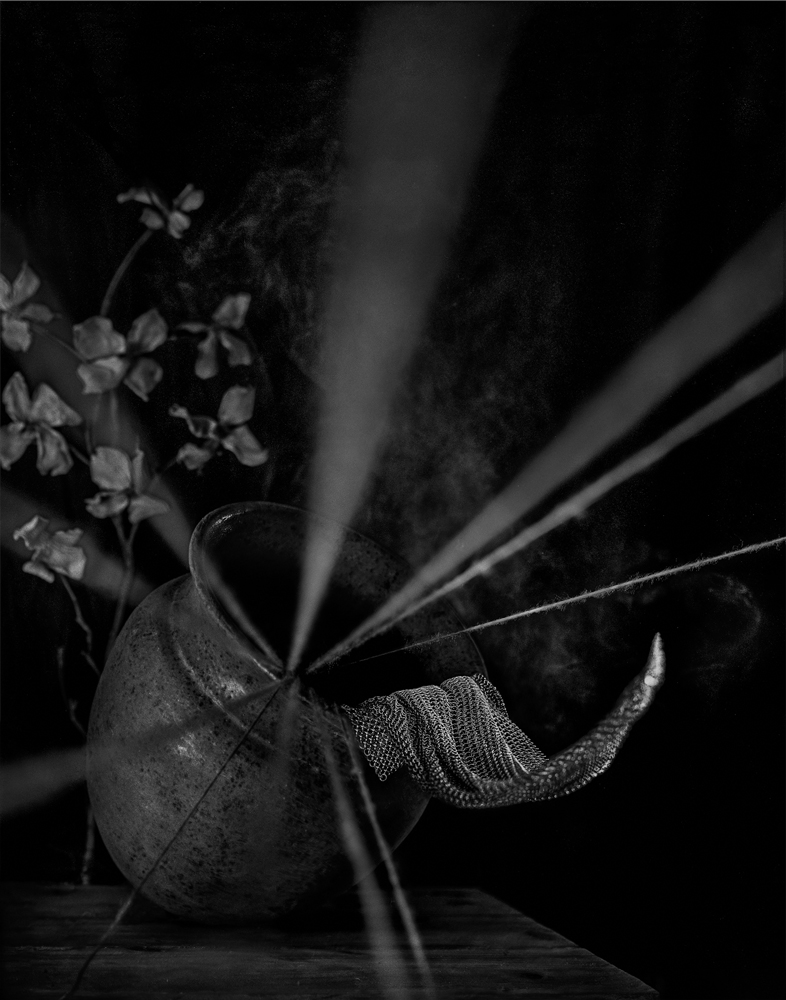

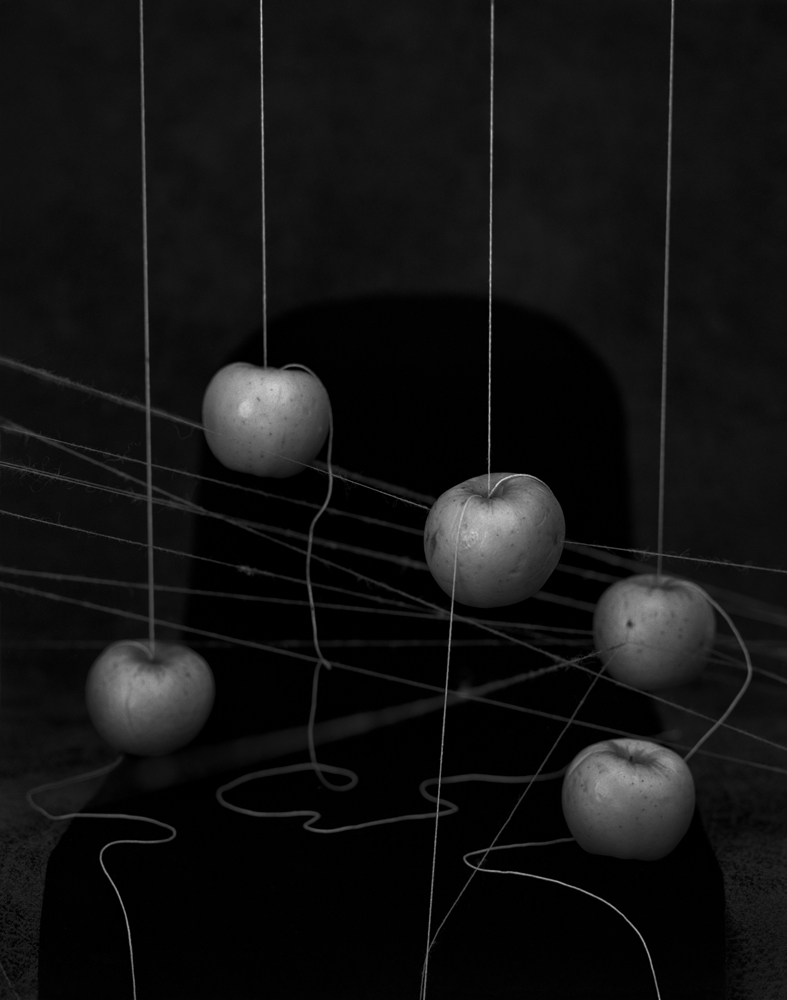

I use symbolic still life and emphasis on the evocative potency of form to suggest the complexity of stories and relationships that aren’t easily shown in a single frame. The works are symbolic and narrative in a way that is abstract and conceptual. They don’t tell a story that is easily deciphered; they stage encounters rather than conclusions.

Through arrangements of natural and constructed materials—flowers, mirrors, string, bone, pigment—I consider how stories unravel and reform across bodies, materials, and time. Like elements with multiple valences, objects and symbols combine differently with each viewer’s experience, creating meaning that is contingent—shaped by context, memory, and proximity.

This work is a visual poem revolving around my thoughts about nuance, dualities, and how we influence and transform each other. The sequence of images—like a sequence of events—suggests how stories bind, unravel, and reform across time and experience, revealing meaning-making as a continuous process. Our lives and rituals of meaning-making are connected even when we are apart. – Teela Misa DeLeón

PPA PHOTO AWARD ‘25 INTERVIEW

Eve Schillo (Guest Juror) x Teela Misa DeLeón (Award Winner)

[EVE] Your images are such a successful blend of photographic representation – recognizable objects, items we can land on and understand – and photography’s unsung ability to embrace abstraction and a different kind of ‘storytelling.’ Can you speak to what compels you in this direction?

[TEELA] What compels me in that direction is the particular way photography can be both a record of what really was and an opening into something beyond the immediate surface. Photography’s relationship to truth has always been unstable—not only because it can be manipulated, or is mediated through power, but because even the most purely representational image can’t contain the wholeness and complexity of life.

Integrity and integration have always been core themes in my life. I am interested in photography’s access to truth in sharing something real, I’m interested in abstraction for how it’s more in conversation with honesty than truth. How we look at painting and see not truth, but something more honest about how the painter feels about this piece of fruit or this body, accentuating its vibrance or vulnerability. I don’t see them as opposites. I want to engage both in their wholeness—to integrate them into a storytelling space.

In this era of constant digital image consumption, I’m drawn to how images might interrupt the easy surface read. Abstraction can be a way to hide, confuse, or collapse trust, and I’m not interested in that. My interest is in how abstraction can open a photograph into the mythic space between what happened and what can be felt—allowing perception to be more expansive and imaginative rather than corroding trust.

A single moment can hold far more than we see at first glance. My work tries to make room for that: an image as a place where truth and mystery can exist in the same breath.

[EVE] Can you speak to the symbolism of the specific materials in your constructed still lives? Or I’ve noted your use of the phrase ‘visual poetry,’ so perhaps strike ‘still life’!

[TEELA] I actually felt very strongly against still life as a genre for many years. I thought of it primarily in its aspect as a display of class—a taxonomy of wealth and refinement. Vanitas and memento mori have been read as bad-faith postures of piety, condemning earthly pleasures while indulging them visually—which is actually pretty funny. But looking more closely at how still life has shaped how we think about objects and symbolism, I wanted to use its architecture to explore and complicate those associations and encoded values.

Not only is symbolism not universal, it’s cultural, it’s also deeply personal. A rose is a symbol of love. Which rose—this rose? No. This rose has a history. It has its own memories of mornings and honeybees and garden shears, and its own history in relation to my life—which is different from how it exists in someone else’s mind, or for my friend to whom a rose was a weapon of abuse. It’s all contingent. We make meaning collectively, and we’re shaped by it collectively.

I choose materials for their charge, for the tensions they hold: a rope that can pull you to safety or bind you; armor that can protect or wound; a line that can connect or refuse. Choosing them is as much intuitive as intentional— like how if you’ve ever been surprised by how something felt in your hands. You expected by its appearance, for it to be delicate and light, but it was firm and heavy and felt like something ancient and enduring in its weight.

They are objects capable of holding history and contradiction—found, forgotten, and lost: a bundle of twine handmade of rose stem fibers and dog fur, an abandoned silver tray half buried in the woods, a brass urn with traces of ash, glass, stone, wood, bone, a bit of lace from who knows where. Elemental, organic, and fluid in time and significance. They touch on hegemonic value systems embodied in easy associations, but resist oversimplification. They become characters with their own bodies, memories, and complexities that can’t be reduced to easy generalizations.

Similarly, neither can we.

[EVE] You spoke about the importance of sequencing and seriality vs. the singular image. Is that just for this series or how you approach your practice overall?

[TEELA] Sequencing and seriality feel integral to my approach and how I think creatively in general. One of the most insightful forms of learning is through mistakes. The only image I ever made that I consider a complete failure was a singular portrait, not part of a larger body of work—it taught me my creativity doesn’t thrive on an individualistic level. My work is most interested in interconnected forms of understanding and how meaning accumulates relationally.

The way that sequencing builds a story feels like a score: repeated refrains and shifts in key, moments that crescendo and fall back, spaces that need the counterpoint of others to be fully heard.

From my own experience as a mixed nonbinary queer growing up in diverse creative queer and trans communities—it has felt natural to always notice gaps and overlaps, all the ways that people’s complexities so often are overlooked or don’t make it into singular frames. The categories available to describe people never fit the whole story—they can almost say something nearly accurate, but not completely.

Meaning is layered and emerges between things—between notes, between identities, between images, between people—not in isolation.

[EVE] I’ve thought of these images as being ritualistic in a satisfying way, but in a way I can’t quite describe further – maybe you can answer that?

[TEELA] How could I possibly? Haha, I’m pleased you have that experience with them. There is a slow and ritualistic process to the quiet stagecraft of bending abstraction into analog space—creating conditions where the photograph can behave like painting, or open the surface to reveal what is otherwise invisible and difficult to name. Anchoring in the real, but opening the space enough for multiplicity to exist without contradiction or erasure—it is my aim to create a safe container for that experience.

I think often about how we engage in rituals of seeing every day, how we have learned or are told to see certain things in certain ways. Here, the ritual space is arranged as open ground for perception—a place to practice seeing multiplicity without confusion, holding contradiction without collapse. An offering that is a threshold for meditating on thresholds.

About Pasadena Photography Arts

Pasadena Photography Arts (PPA) is dedicated to promoting diverse photography projects by established and emerging photographers worldwide. Through a series of both in-person and virtual events, PPA is creating a global art community for photographers, by photographers. To achieve the mission, PPA’s ongoing programming includes FORUM where we invite special guests including museum curators, art educators, and long-established photographers. And through Open Show – Pasadena/East LA, we support the projects of emerging and professional fine art, documentary and conceptual photographers. We hope to see you at a future event!

Follow us on IG: @pasadenaphotoarts

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)October 1st, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: George Nobechi (2021) and Ingrid Weyland (2022)September 30th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Amy Friend (2019) and Andrew Feiler (2020)September 29th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Jennifer McClure (2017) and JP Terlizzi (2018)September 28th, 2025