The Female Gaze: Anne Berry – Ode to the Blue Horses

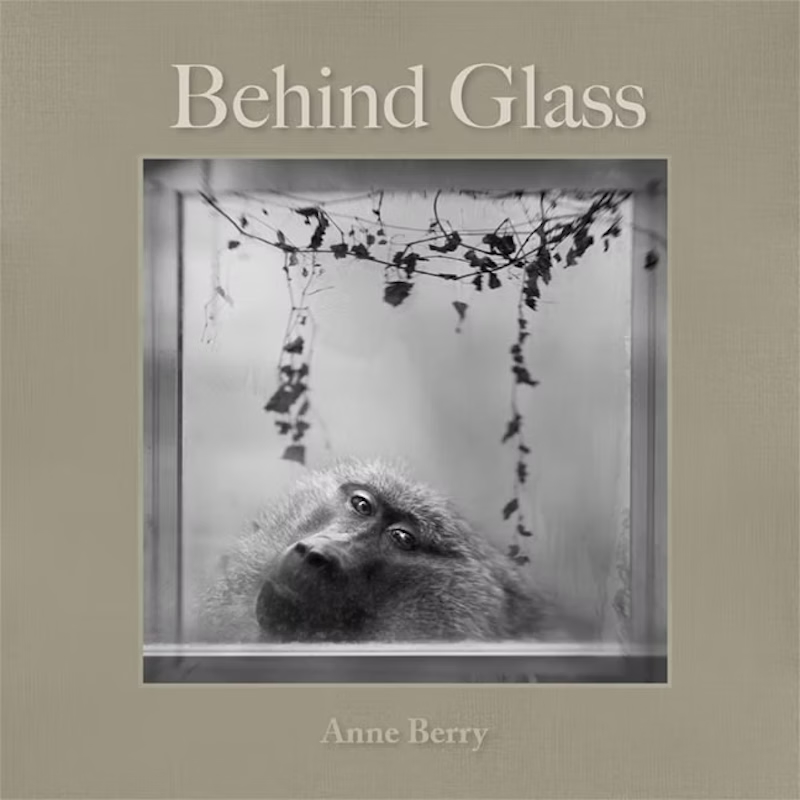

Anne Berry is an artist from Atlanta, Georgia. Berry’s photographs investigate the animal world, the domain of childhood, and the terrain of the Southern wilderness. The memories, stories, and settings of Berry’s Southern upbringing have influenced her work, infusing it with a darkly romantic, Southern Gothic feel. In 2013, 2014, and 2024, Critical Mass included Berry’s work in their Top 50 Portfolios. She has had solo exhibitions at the Centre for Visual and Performing Arts in Newnan, GA, the Lamar Dodd Art Center in LaGrange, GA, and the Rankin Arts Center in Columbus, GA. She has exhibited nationally and internationally, including at The Fox Talbot Museum in Lacock, England; SCAN Tarragona in Spain; The Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego; and the Ogden Museum of Southern Arts in New Orleans. Books include Through Glass (North Light Press, 2014), Primates (21st Editions, 2017), and Behind Glass (2021). Berry’s work has been featured in National Geographic Proof, Feature Shoot, Huffington Post, and Lens Culture, among others. Her work is in many permanent collections, including the National Gallery of Art.

I’ve been following Anne Berry’s work for years, mainly from the distance, admiring works I wish I had made. I’ve been taken by the Southern coast background of many of her works….I find something timeless and magical within the frame of these images. Berry characterizes that look as “Southern Gothic”, but, to be honest with you all, I am not really sure what that means. Other than one trip long ago traipsing from one end of Florida to the other, I haven’t spent any time in the South…unless, unlike me, you count the mega amusement parks as “the South.” I only know what I see in photographs.

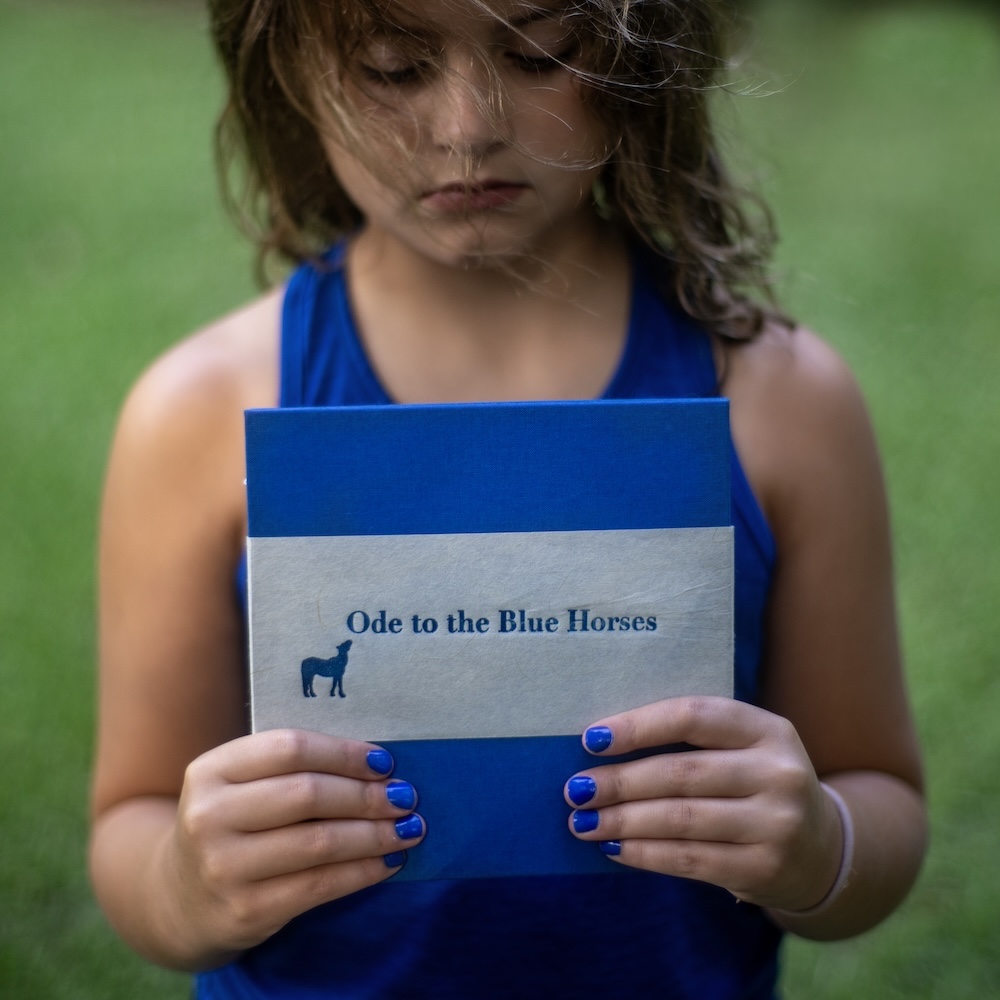

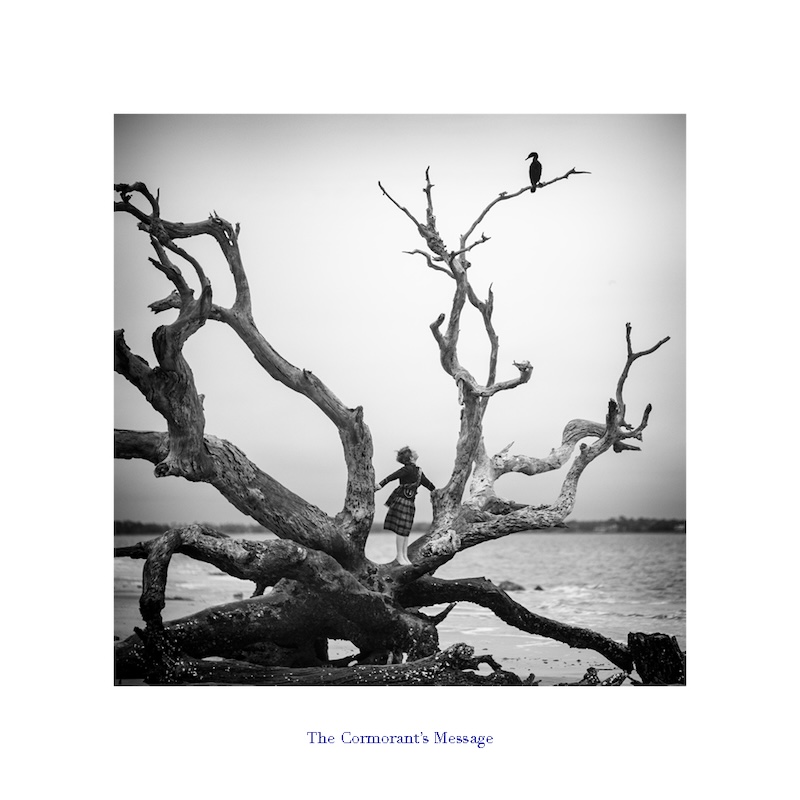

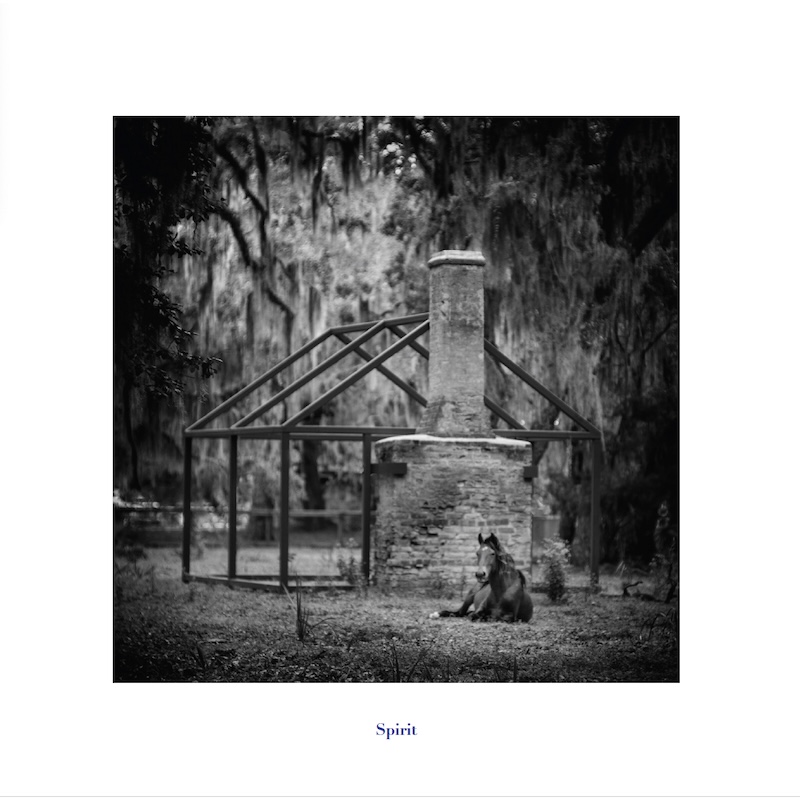

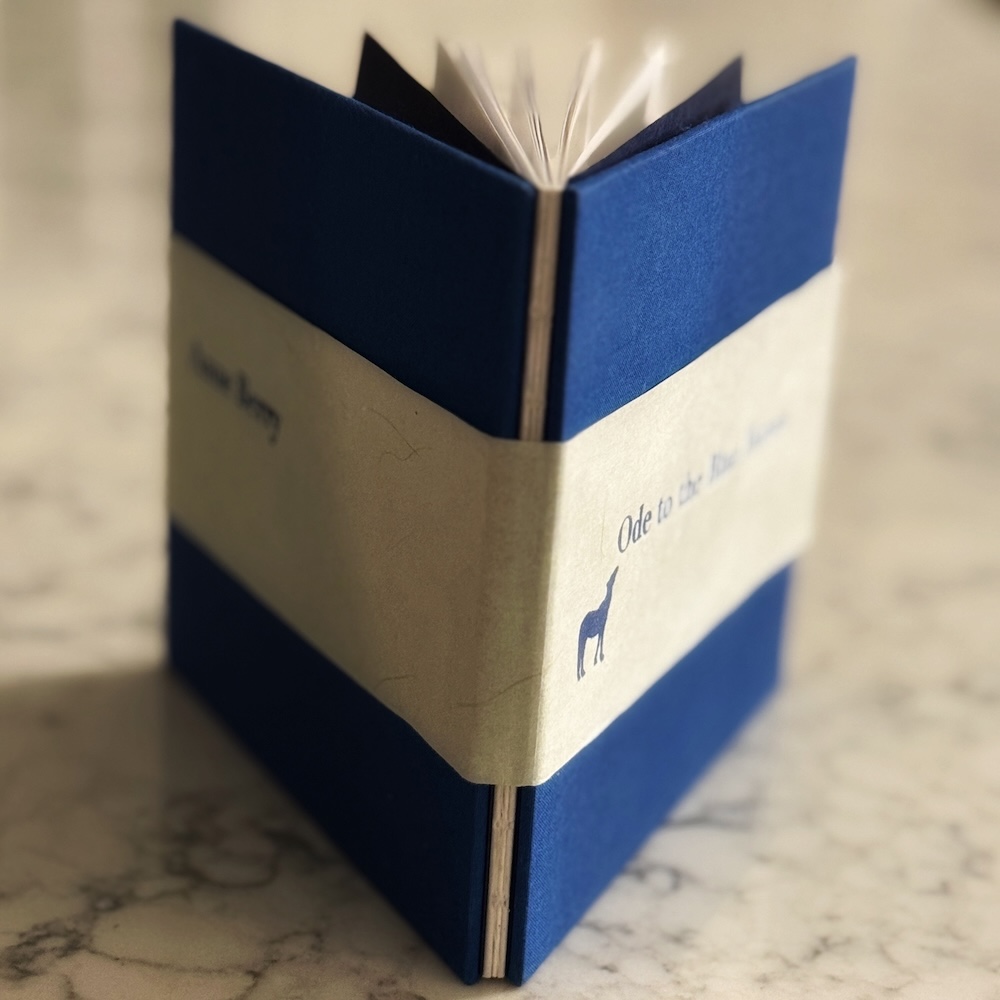

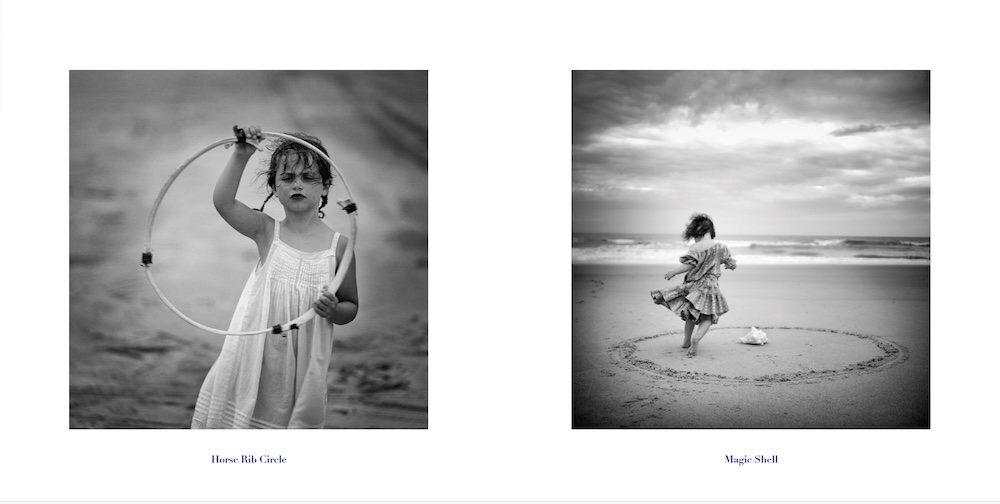

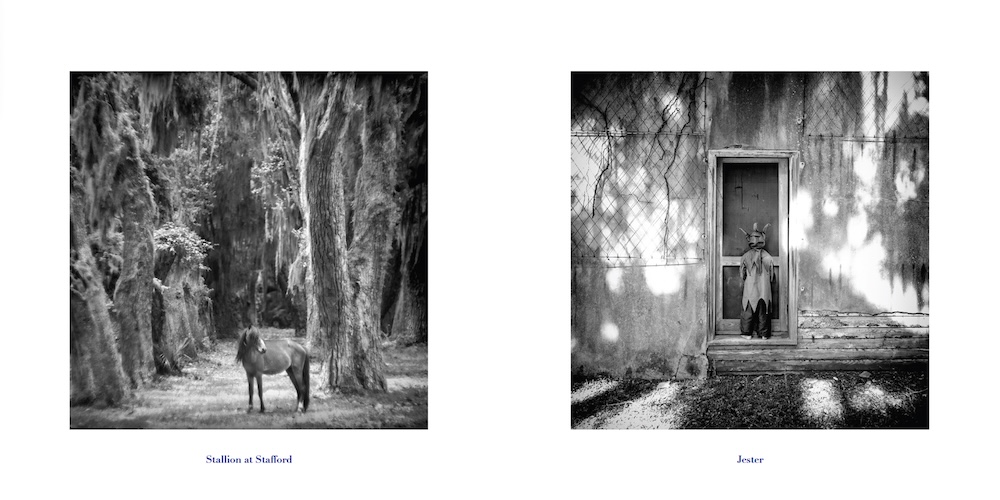

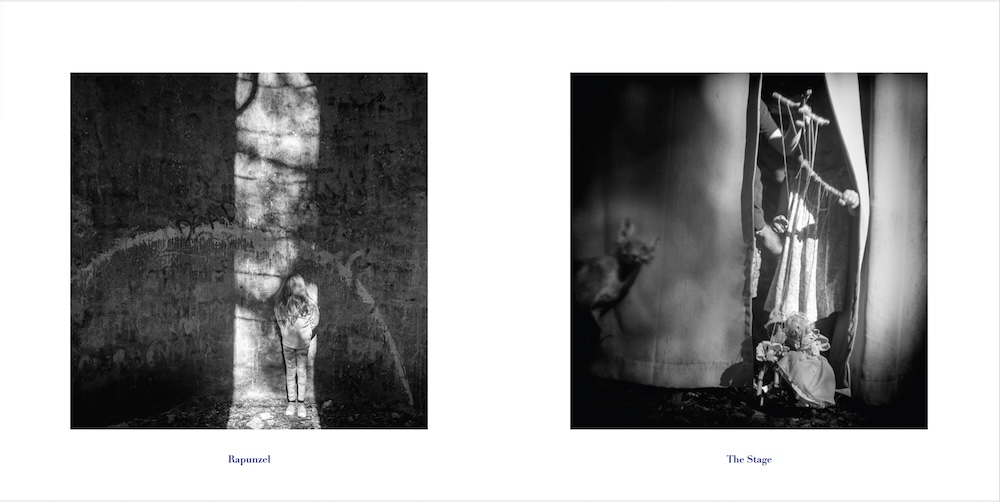

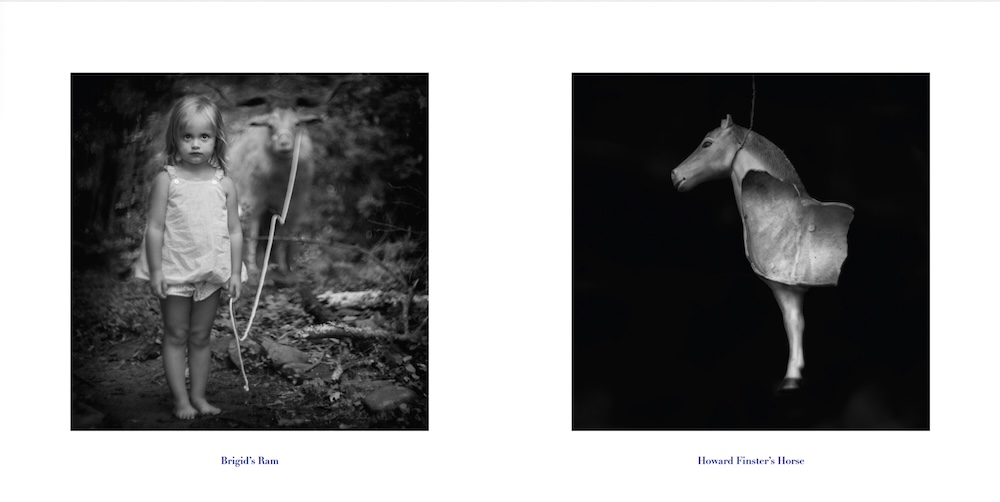

As soon as I saw Berry’s book, Ode to the Blue Horses, cross my Facebook timeline I knew I wanted to own it. This is not something I say frequently, as I literally have no space for a book collection…mostly every book I own is on Kindle or Audible. But I was entranced by the nod to the handmade that the book had, the reasonable price, and so, knowing I love her imagery, I jumped without seeing any content. And I am glad I did. The book arrived a few weeks ago, and it is everything I hoped it would be. I love the open spine, and the hand-printed belly band. The photographs, culled from an earlier series, are paired to prompt the viewer to make their own connections between the childhood activities and the lands they take place on. They are imbued with magic and a sort of wistful melancholy. The images evoke my own memories of my small town New England childhood adventures exploring the land behind the neighborhood’s homes, acting out stories and picking wild berries.

Although the focus of this feature is Berry’s book, I have included additional questions to put some context around her practice. I hope you enjoy reading about Berry and her work.

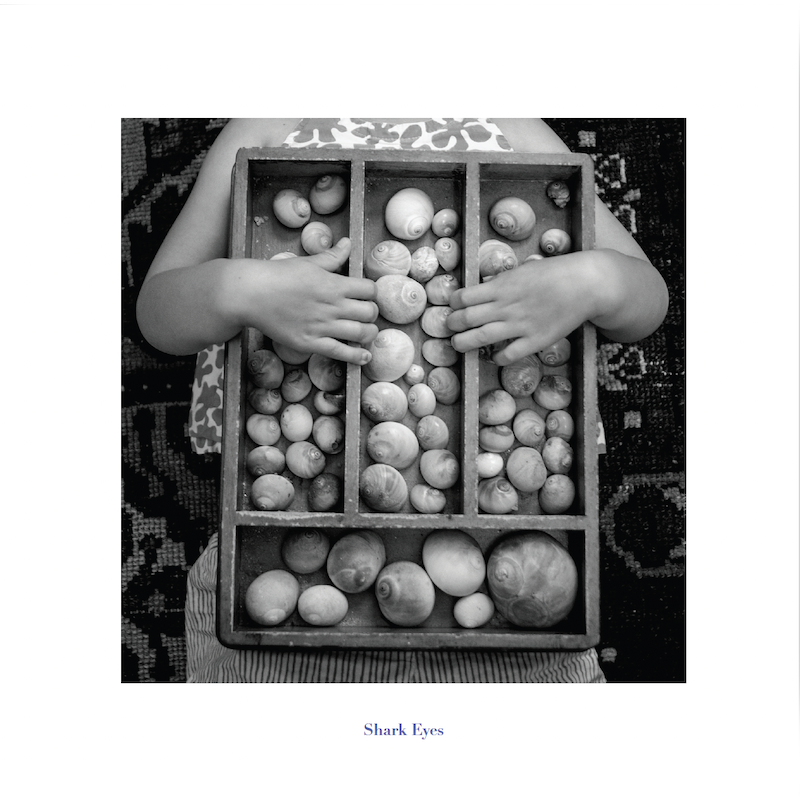

©Anne Berry – Porcupine’s Protection from the book Ode to the Blue Horses and the series Ode to Enchantment

DNJ: What were you like as a child?

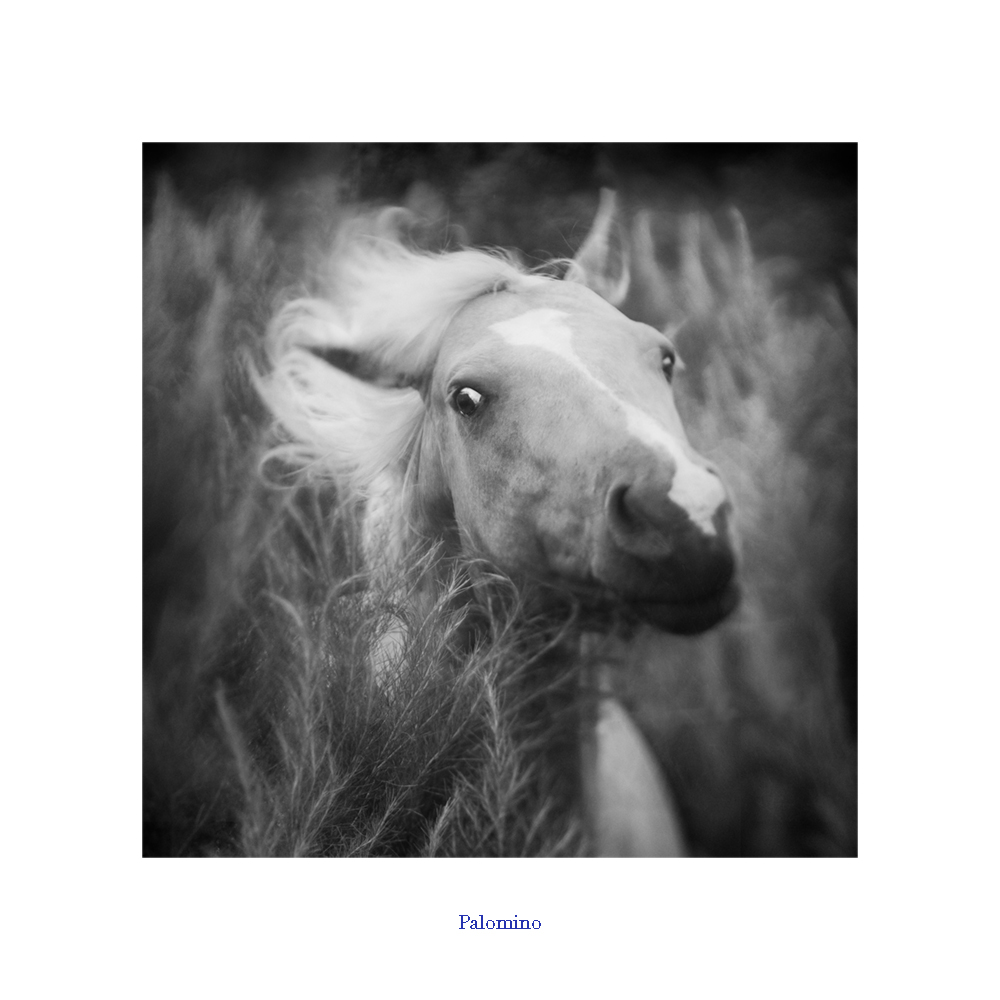

AB: I grew up in Atlanta, GA. As a child, I spent most of my time outdoors in our woods and creek with my three brothers, building forts, raising frogs from tadpoles, catching crawfish, and the snakes that sunbathed lazily on the asphalt driveway. I played in nature and with our dogs, rather than with dolls. I was obsessed with horses. That passion informed many of my early decisions. Art was always present. I looked at art in books and in museums, took painting lessons, made figures out of clay, and carved Ivory soap.

DNJ: If you remember when you took your first photograph, did it contribute to your future love of photography?

AB: During college my grandfather gave me my first camera, his old Nikkorex. I always approached looking at and making photographs the way I would make a drawing or painting; I was never interested in documentary photography.

©Anne Berry – I Have Had A Dream from the book Ode to the Blue Horses and the series Ode to Echantment

DNJ: What did you study in college?

AB: I went to a small liberal arts college on 3,000 acres in rural Virginia. I majored in English and art, but my passion was still horseback riding. I rode five or six days a week and planned to teach English and art so that I could ride every afternoon, which I did until I married. Later, I happily swapped riding horses for raising my three children.

When did you figure out art was your career path, and how did that happen?

AB: The void left by the absence of horses made room for my dormant passion for art to develop. I took photography classes in college, learning to make silver gelatin prints. I was practicing a craft, and I had not yet found my passion. After college, I experimented with different media: oil and watercolor painting, ceramics, and Polaroid transfers. Around 2009, I started studying photography and making silver gelatin photographs again. Polaroid had stopped making film, and Nikon introduced a digital SLR. Eventually, I started using the latter with a vintage Zeiss Jena 85 mm lens made for a medium format Pentagon Six camera. The adapter allowed me to tilt the plane of focus up to 9 degrees. This combination gave me the look I wanted, and at f2 I was able to shoot with natural light in primate houses for the “Behind Glass” project. I knew from the first images in this project that photography would be my path and my passion.

©Anne Berry – Donkey’s Parade from the book Ode to the Blue Horses and the series Ode to Enchantment

DNJ: Your earlier book, Behind Glass, received international acclaim. Jane Goodall wrote a message for it, which is very special to my thinking. With her recent passing, do you have any thoughts on Goodall’s involvement with your project?

AB: I’m honored to have been able to communicate with Jane Goodall about “Behind Glass” and to have received her kind words and encouragement. She understood what it meant for the primates in zoos to have visitors. Goodall stressed the importance of small actions. My photographs of primates won’t change the world, but they evoke empathy, and I hope that they will motivate people to feel compassion for primates and an obligation to protect them.

DNJ: Where do the ideas you work with come from?

AB: There’s a Southern Gothic atmosphere in all my work. I grew up with bluegrass ballads, cemetery wanderings, and ghost stories. We were frequent visitors to Andersonville Prison camp, and the Battle of Atlanta Cyclorama was a yearly school field trip. These repeated experiences of war’s sadness and destruction, the ballads of murder and death, and dwelling on the stories inscribed on tombstones contribute to a tendency towards a particular kind of imagery—poetic and haunting. But beneath this aura of longing and loss is beauty and mystery, a universal search for meaning: the wounded Fisher King searching for the grail that will heal both himself and the dry, sterile land.

DNJ: Can you share your typical work process with us?

AB: I use vintage analog lenses, and I shoot with a wide aperture, so I’m manually focusing on a small area. When I’m photographing animals, this process involves patience as I wait for them to appear and assume a stance, gesture, or expression.

I look for similar things when photographing children. These photographs are more constructed, but most often the gesture, expression, or use of a prop comes from the child rather than my direction.

In my latest project, I am experimenting with self-portraiture using prolonged exposure. I usually place myself as a ghostly figure in the setting of a ruin. This project is new and still unresolved.

DNJ: From my side of the table, you appear to have a full-hearted love and spiritual connection to the island country of Georgia. Is that accurate? How did that start?

AB: I spent the summers of my childhood in a little cabin down a red clay road on a lake in North Georgia. I loved the fog coming of the lake’s clear water in the morning and the solitary trips I made in my blue and white rowboat. That place only resides in my memory; it’s now all mansions and fast boats.

Now it is the landscape of coastal Georgia that captures my heart and my imagination more than any other place. There are fourteen islands off the coast of Georgia, ten of them remain undeveloped, separated from the mainland by marshland, populated by Yaupon holly and live oaks covered with Spanish moss, alligators, bobcats, shorebirds, and sometimes, feral hogs left by Spanish explorers, feral horses, Sicilian donkeys, and even a colony of lemurs.

A close friend shared Cumberland Island with me over 30 years ago, and it remains special. I visit the coast many times a year with my family. Since 2011, I’ve organized at least one annual trip to one of the wilderness islands with artist friends and colleagues via Pigs Fly Retreats and the Southern Wild Artist Residency. Magical things happen when creative people meet to work in this unique and fairy-like environment. Some of that work can be seen on my website in Addison Brown’s video of the “Touching Magic” traveling exhibition.

DNJ: I’d like to explore your latest book, Ode to the Blue Horses. Could you tell us about it?

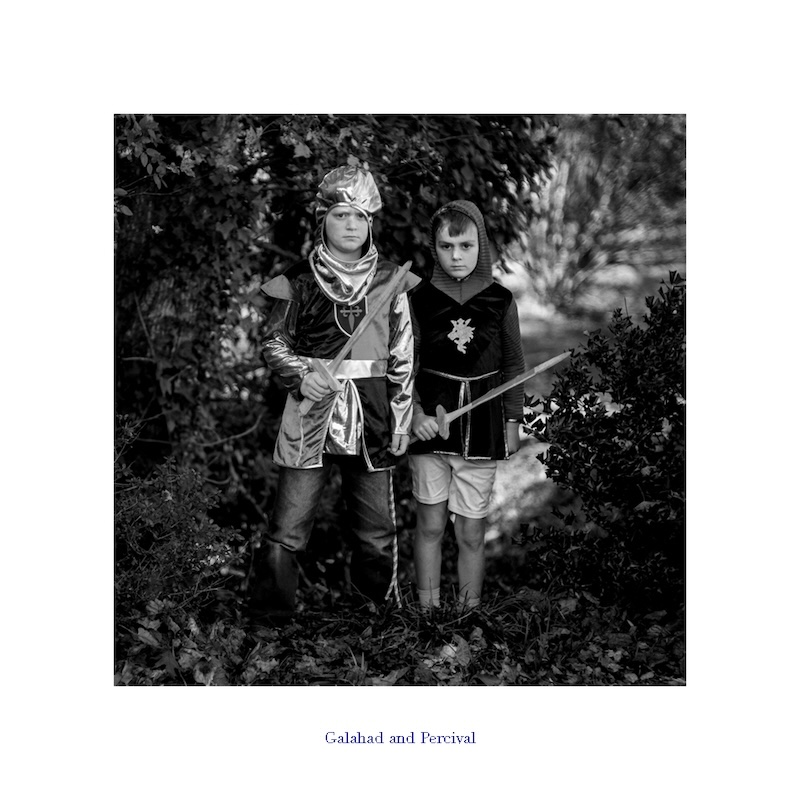

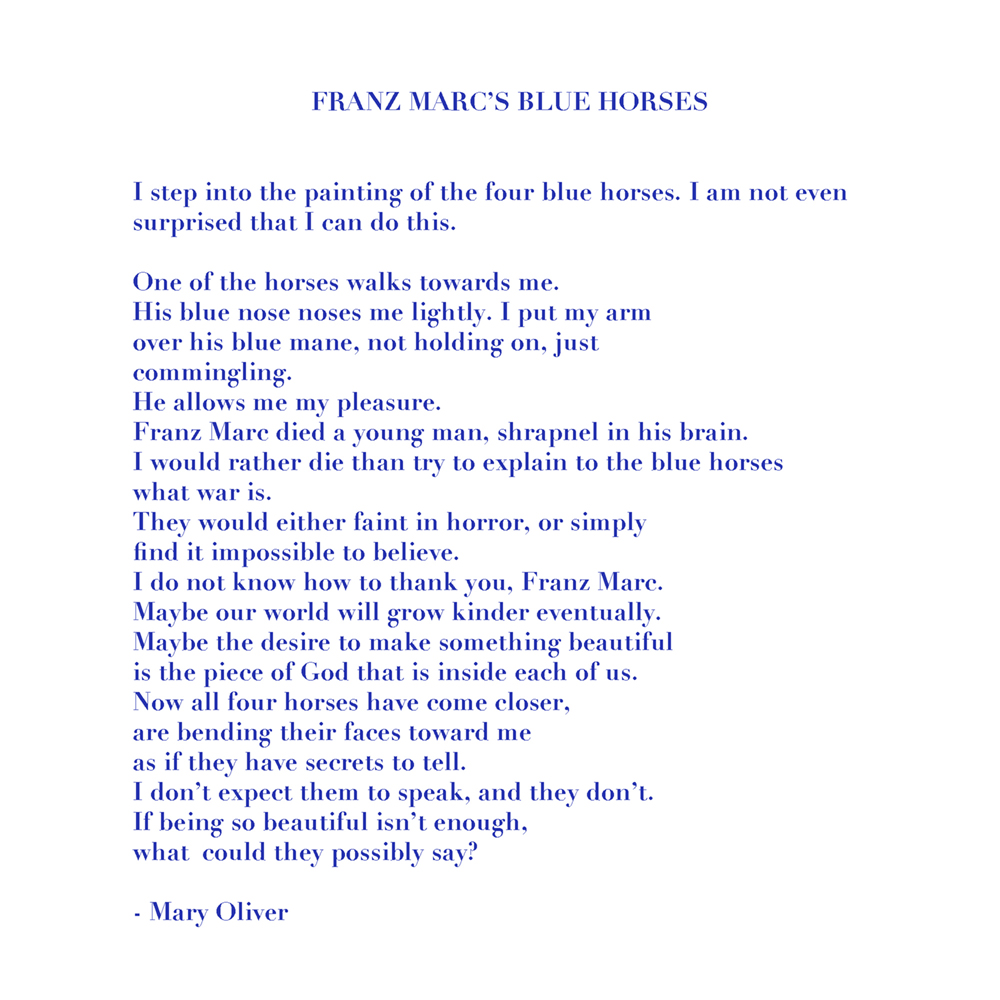

AB: My idea was to self-publish a small object of beauty that would offer value for supporters of my work. The book is a signed and numbered edition of 100 with a hand-pulled photogravure on mold-made paper included. Mary Oliver’s poem, “Franz Marc’s Blue Horses” by Mary Oliver, which is the focal point of the book. The poem is melancholy—shadowed by the war that killed Franz Marc, but also by the importance and power of beauty. The absence of color and the shallow focus suggest another reality, where magic rules and animals comfort and guide. Doors and windows are portals to uncertainty in the same world where a child runs joyfully around a circle, a symbol of eternity. The color blue might reference sadness, but it is also associated with strength, spirituality, and eternity. The reference to the color blue in a world otherwise monochrome, as well as the horses themselves, signifies something spiritual.

For this book, I grouped images from two series, “Ode to Enchantment” and “Land of the Yaupon Holly.” The photographs speak to one another and reference or echo themes touched on in the poem. Brilliant Graphics printed the duo-tone image pages and bound the book with an exposed spine. The fabric-covered hardcover is blue, and I attached a belly band of Japanese kozo onto which I letter-pressed the title.

The photographs hint at magical things, probing a mystical force that exists between the mundane and the superficial. Franz Marc’s horses touch this mystery and beauty that Mary Oliver speaks about in her poem. It’s the magic that allows us to step into the painting. It’s the source of hope that Jane Goodall begs us never to lose.

DNJ: What is next on the horizon for you?

AB: I’m getting ready for a two-person exhibition with Kirsten Hoving at Jo Brenzo’s The Photographic Gallery, which is an elegant little gallery in San Miguel de Allende, a charming city full of colonial architecture. The exhibit will run from January 16 to February 14, 2026. Kirsten and I will both attend the opening on the 16th; we would love to see some friends there!

DNJ: Thank you ever so much, Anne, for taking the time to speak with me today. I really look forward to seeing your ghostly self-portrait series come to life.

Note to readers: Ode to the Blue Horses is available for purchase from Anne Berry here.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The Female Gaze: Anne Berry – Ode to the Blue HorsesNovember 13th, 2025

-

The Female Gaze: Lara Gilks – Just Outside the FrameOctober 23rd, 2025

-

The Female Gaze: Jane Szabo – Recent WorkSeptember 21st, 2025

-

The Female Gaze: Karen Klinedinst – Nature, Loss, and NurtureAugust 23rd, 2025

-

The Female Gaze: Judith Nangala Crispin – A Committed PracticeJuly 31st, 2025