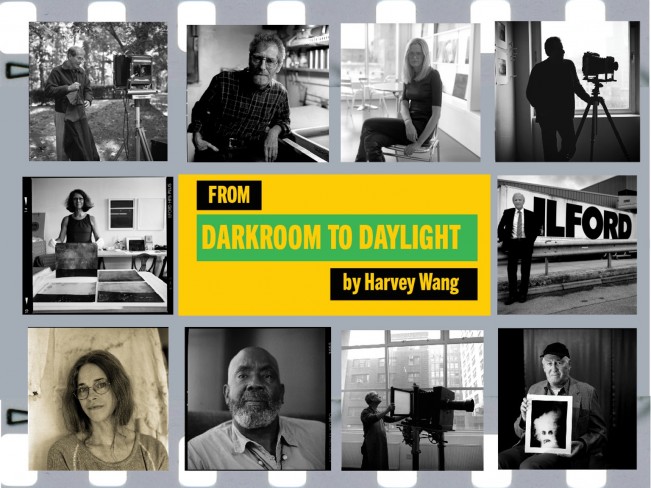

Harvey Wang: From Darkroom to Daylight

As a film photographer, I am intrigued by and appreciative of the heroic efforts of photographer and filmmaker Harvey Wang to examine the state of photography in 2015. His efforts have resulted in a book, From Darkroom to Daylight published by Daylight Books, and a movie with the same title. The project began as a personal exploration of how the dramatic change in photography from chemical to digital processes has affected photographers and their work. At first, a love letter to the silver process and darkroom, From Darkroom to Daylight touches on the history of photography, the coming of digital, and what became possible with digital methods. The story is told through the voices of many artists whose work and methods embody various aspects of the story. Harvey has spoken with over 40 important photographers including Sally Mann, David Goldblatt, Platon, Sid Kaplan, Richard Sandler, Jeff Jacobson, Stephen Wilkes, Constantine Manos, Gregory Crewdson, John Cyr, Alfred Gescheidt, Adam Bartos, George Tice, Jerome Liebling and Susan Meiseles.

As a film photographer, I am intrigued by and appreciative of the heroic efforts of photographer and filmmaker Harvey Wang to examine the state of photography in 2015. His efforts have resulted in a book, From Darkroom to Daylight published by Daylight Books, and a movie with the same title. The project began as a personal exploration of how the dramatic change in photography from chemical to digital processes has affected photographers and their work. At first, a love letter to the silver process and darkroom, From Darkroom to Daylight touches on the history of photography, the coming of digital, and what became possible with digital methods. The story is told through the voices of many artists whose work and methods embody various aspects of the story. Harvey has spoken with over 40 important photographers including Sally Mann, David Goldblatt, Platon, Sid Kaplan, Richard Sandler, Jeff Jacobson, Stephen Wilkes, Constantine Manos, Gregory Crewdson, John Cyr, Alfred Gescheidt, Adam Bartos, George Tice, Jerome Liebling and Susan Meiseles.

The film took five years to complete and was shot by cinematographer Derek McKane and a talented group of other shooters, edited by Edmund Carson, and scored by Stephen Greenberg, Jeet Baidyaroy, and Jesse Maynard. Everyone involved has donated their time and talents.

I visited the Ilford factory in England to talk to Howard Hopwood about film production, and spoke with Steven Sasson, who invented the digital camera while at Kodak. I was also able to meet with Thomas Knoll who recounted how he and his brother invented Photoshop, the software that changed the world.

Much of my own published photography has been about disappearance–of trades, neighborhoods, ways of life–and to live through this transition in my own craft has enabled me to document the state of the art as both an insider and also as a documentary photographer.

The initial support for the project came through a grant from The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. I’ve also received a grant from The Adobe Foundation. All the interviews will be housed at The Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona in Tucson upon completion of the project.

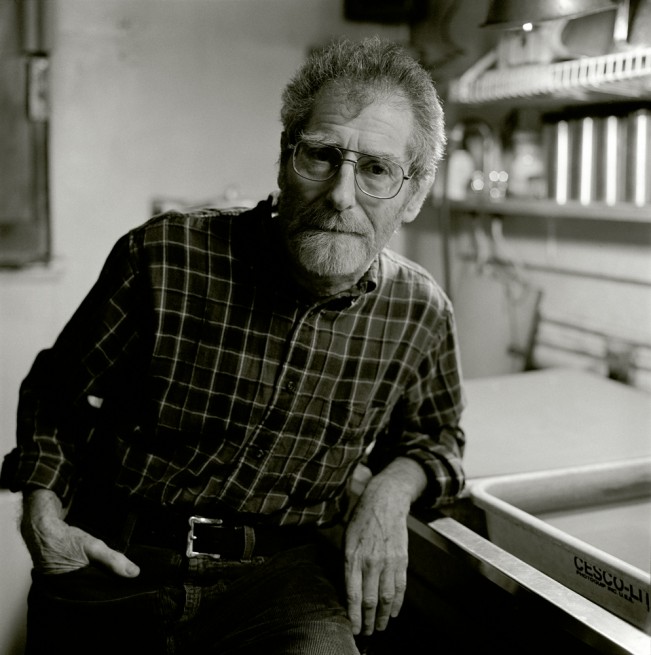

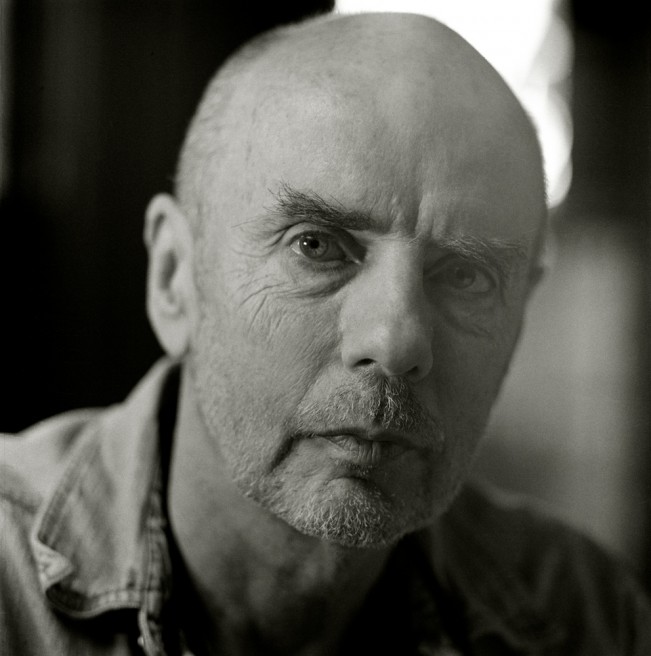

Sid Kaplan

Photographer, Educator, and master printer for anyone and everyone, including Edward Steichen, Robert Frank, Weegee, Louis Faurer, Allen Ginsberg, W. Eugene Smith, Cornell Capa, Philippe Halsman, and Duane Michals.

Interviewed by Harvey Wang on November 18, 2008, in his darkroom in New York City

One time my grandson was here and I was printing. So we’re talking while I’m printing, and I

started saying, yep, I’ve been doing this from 1955 till now, 22-hour days, it just goes on and on.

And he’s listening to all of that, and then at the end he says, “When you’re doing that all that

time, what are you thinking?” And I said, “Everything, from the minute I was born to what I

gotta do for the future.” Unless you’re talking to somebody else who does this thing there’s no

way of ever explaining why you do it.

In some ways I think right now I’m exactly where I was 60 years ago, where anybody that had a

wet darkroom in their house was somewhat unusual. People say, “Oh, you’ve got a darkroom in

your house?” And I say, “No, the whole house is a darkroom, and I just found a corner to

sleep in.” The adventure, though, is still getting a good picture. If I thought about all this other

stuff, about where it’s going or where I’m heading, it wouldn’t be fun. I’m at the point that it’s

time to start wrapping things up. If there’s no more developer around, no more Dektol, no more

paper, well I got my 60-year merit badge. But there’s still a few more negatives I’d like to

print.

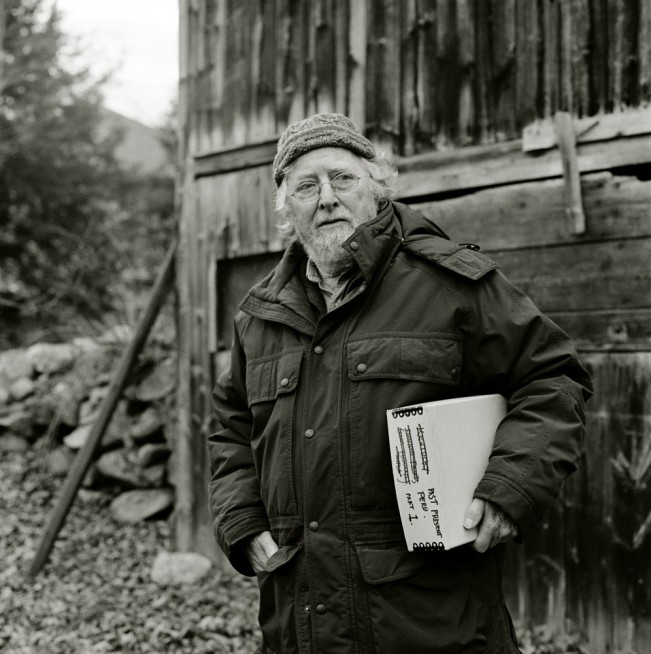

John Cohen

Photographer, filmmaker, musician, musicologist, distinguished educator

Interviewed by Harvey Wang on November 18, 2008, at his home in Putnam County, NY

When I see something that’s exciting to me—that’s a good situation. It’s the excitement that counts, not whether it’s digital or analog. Of course, I’m talking from a weird perspective. One of the recordings that I made in Peru, of a little Peruvian girl singing a song unaccompanied, was put onto a gold-plated phonograph mounted onto the side of the Voyager spacecraft. It’s going to be out there for a while. It’s outside of the solar system. I don’t know who’s going to listen to it, if they’re going to like it or not. But, you know, you get into these weird, odd moments that make the whole discussion about photographic media seem stupid. But we live in the stupid world and not out in outer space.

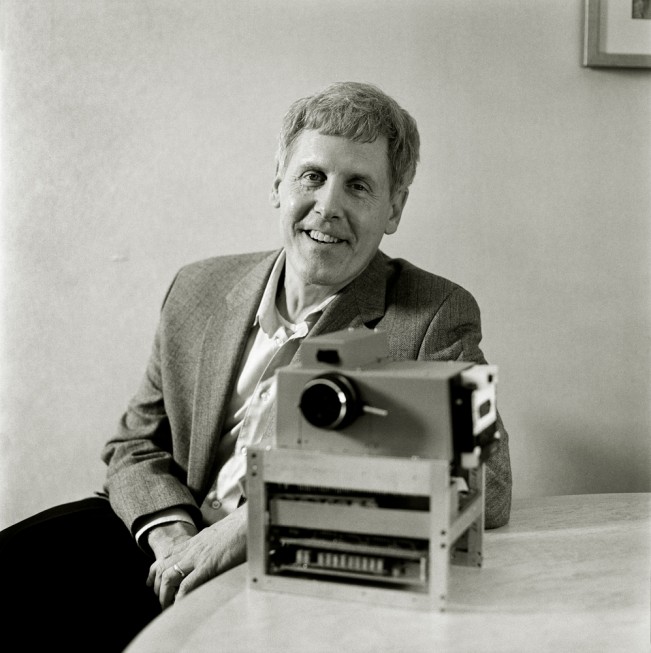

Steven Sasson

Electrical Engineer at Eastman Kodak Company (Retired) co-Inventor of the Digital Camera

Interviewed October 17, 2009, in Rochester, New York

Film is an incredible technology. It always has been, and it remains that way. Think about it—that little piece of film you can put in your camera. It gets manufactured somewhere; it can be stored on shelves for years, put in a camera, any camera, taken anywhere around the world, and then for a fraction of a second be exposed to light; and it retains that image maybe for years, until it’s developed. And then that same piece of film is used for maybe projecting onto a print, right? Well there’s no single element in the digital chain that even comes close to what that piece of film does. It’s really amazing when you think about it. The electronic approach decomposed the elements of that film into different functions. And all those functions were developed, and a microprocessor came along, digital signal processing, digital memory came along, CCDs came along. So it decomposed that whole chain, you know, made it all come together in the digital camera. But that piece of film did everything, all by itself. You’ve just got to marvel at that.

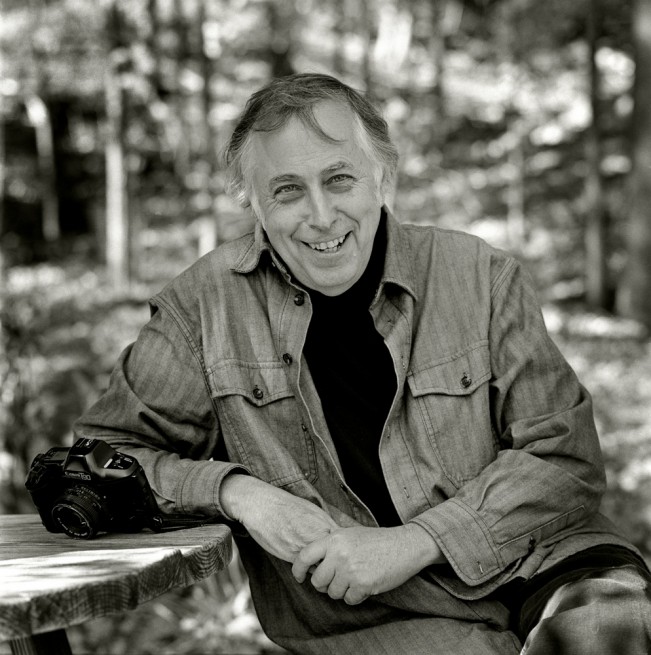

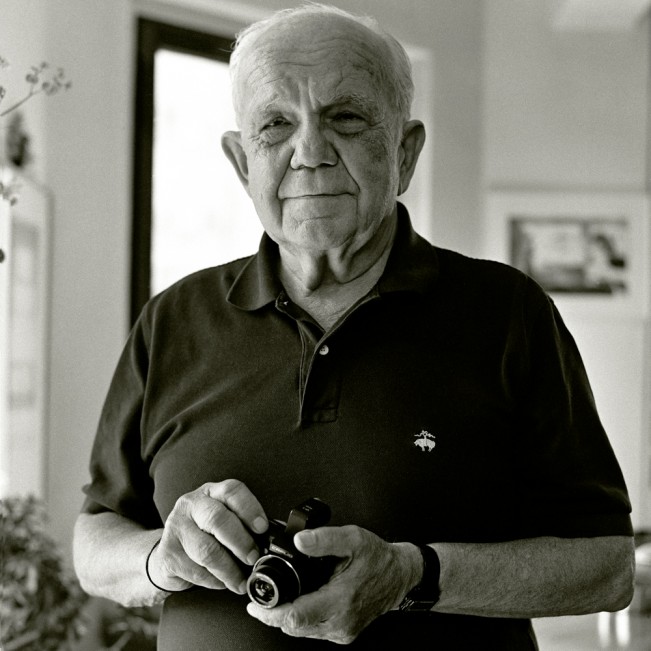

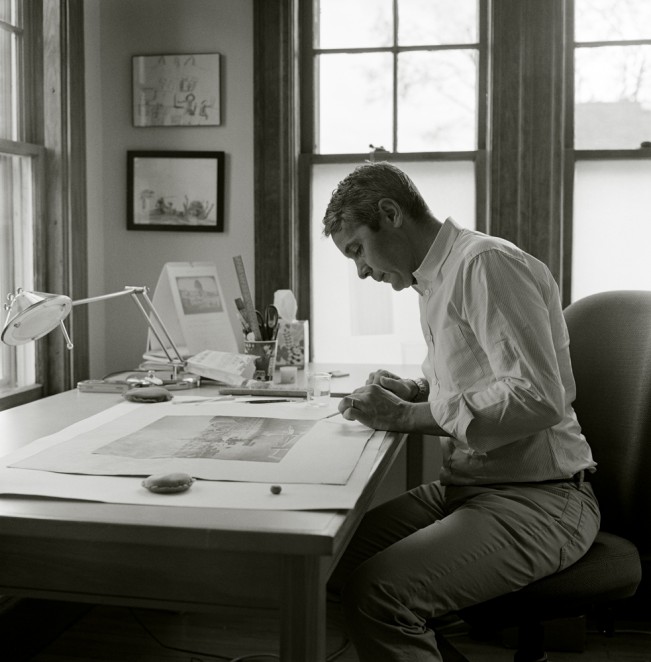

Jeff Jacobson

Photographer

Interviewed by Harvey Wang on September 29, 2009, at his home in Mount Tremper, New York

It seems to me that digital is about post-production. That’s where the magic happens. Kodachrome’s about the moment of shooting. Still photography used to be, you go out, you may be on the road for a week, two weeks, a month, whatever, you wouldn’t see anything. So the process is going on in your unconscious, and digital brings that up to the conscious. I think that’s a real change in photography, and I’m not at all sure it’s a change for the better.

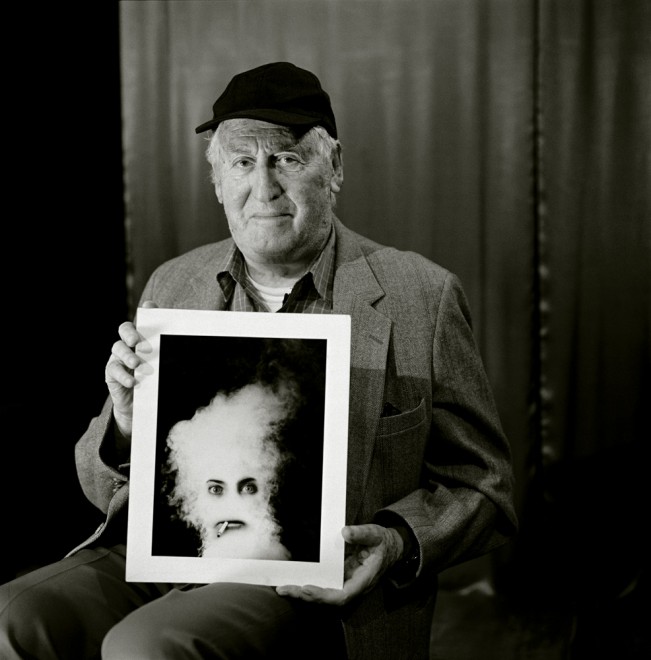

Alfred Gescheidt (1926–2012)

Photographer

Interviewed by Harvey Wang on February 3, 2011, at his home in New York City

You still have to have an idea. And you have to be able to execute it. A computer would certainly make a lot of this much easier. Yeah. But I don’t feel in a way that I missed anything. I did what I had to do the long way, the short way, the complicated way, the throw-out way, whatever way it was. I just stayed with it, and so it doesn’t bother me. I mean, if I was 25 years old and was in the field, I’d certainly have a computer. That’s the way it goes. But the idea is king, however you do it. I would never walk in a room and say [of myself], “Here’s a guy that doesn’t use computers, he doesn’t even know what Photoshop is.” Let them say that. And they say, “Hey, how’d you do that without Photoshop?” Well, I did it the hard way. Man Ray didn’t have computers.

Mark Bussell

Photographer, Former Picture Editor of the New York Times and New York Times Magazine

Interviewed March 17, 2011, in New York City

There’s a tendency to love what you know and not to want to give it up, especially when new things happen. But, you know, people probably felt that way about their horses when trains and cars were invented. And so, while I wasn’t dying to let go of Kodachrome or black and white,

I also realized that digital had some potential. This had the potential for moving images quickly, for changing them, for distributing them in ways that didn’t exist before. And while I had no idea of where it might go or end up, I found it intriguing.

As a kid, I had an acoustic guitar. Got a little older, got an electric guitar. It didn’t mean that the acoustic guitar that I had, or any great acoustic guitar playing that I ever heard, was less meaningful. In fact, it’s enhanced by the fact that there’s even more that you could judge and compare it to. So I think black and white to color is acoustic to electric.

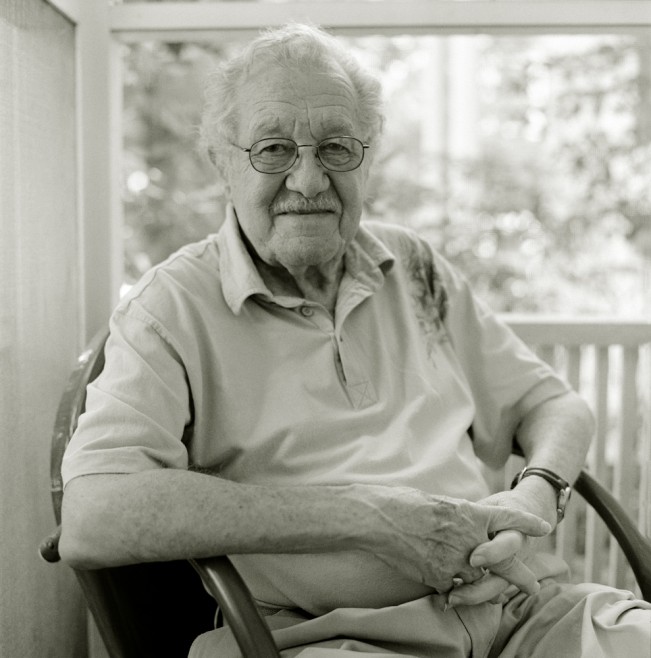

Jerome Liebling (1924–2011)

Photographer, Photo League, and Distinguished Educator

Interviewed by Harvey Wang on August 11, 2009, at his home in Amherst, Massachusetts

The computer is here. It is here. And how deeply it’s here, and how it’s changing the facts of life is what you’re searching for. People say, “Hey, Jerry hold still,” and they take out the telephone and they take a little picture. I don’t know where it goes or what happens to it. I think within photography, the cusp is over. The daguerreotype is dead; the dry plate is dead. Can you go back and make a dry plate? Yeah. A wet plate, or whatever they call them, an ambrotype? Yes. But so what? If I walk through the streets with my Rollei, people say, “Oh, is that a new camera?” I think the scariest term was when somebody said, “Oh, Jerry, you still practice alternative processes.” That the negative, and film, is an alternative process? It’s not a frontline process! That hurt. [laughs]

Alison Nordstrom

Independent Writer/Curator

Interviewed October 17, 2009, at George Eastman House, when she was Senior Curator of Photographs, Rochester, NY

I think we have changed the nature of how we make photographs, which has caused us to change the nature of how we keep photographs. But I don’t think that has yet changed the way we

think about photographs. And even the way we make photographs—it’s changed technically, but not culturally. And that’s not surprising.

There’s been discussion in my field about, you know, let’s start in 1839 and let’s end in 1980 and just sort of say this was this time of the chemical photograph. But I’m not so interested in the photographs as I am in the people who made them, cared about them, or didn’t care about

them, and I don’t see why I should shut the door on the 100 pictures on your iPhone. And again, technically, we can figure out how to save your phone and how to save the pictures on it, and we can interpret them in the context of photographs people have been treasuring of people theylove ever since they could have a photograph.

Charles Harbutt

Photographer, Distinguished Educator

Interviewed by Harvey Wang May 20, 2010, at his home in New York City

The problem for photographers still is very simple: What do you point the camera at, where do you stand to point it, when do you shoot? How do you record and deliver the image? Students are far superior to me in their ability to work with Photoshop. But what they’re doing with Photoshop is really—some of them aren’t—but many are so used to the perfect image from advertising that they shoot what to my mind is a dull photograph, something that illustrates some concept or theory. They then spend weeks and weeks spotting it, getting the colors right, blowing it up to mural size. And you look at it and you think, you did all of that? Why? What’s the point? I remember the delight I had when looking at Robert Frank’s retrospective book and discovering a lovely picture of Mary Frank and Pablo with a huge unspotted hair. Yes, I thought, that’s what photographs look like in their natural state. A very liberating idea. Who cares about perfection? The world’s not perfect, so a perfect picture is a lie.

Thomas Knoll

Co-Inventor of Photoshop

Interviewed October 24, 2012, in New York City

The original reason we did Photoshop was because it was really fun to manipulate images on a computer. We weren’t thinking of any practical uses of it at all, but as soon as people saw that they could manipulate images very easily on a computer, they developed uses. And every time I watch really good users using Photoshop, I’m amazed by the variety of things they can do with it, that I would never have thought of when I was writing the program.

I’m still the first name on the Photoshop splash screen. Fortunately, it’s just a name and it’s not a face, and I can live a fairly anonymous life most of the time.

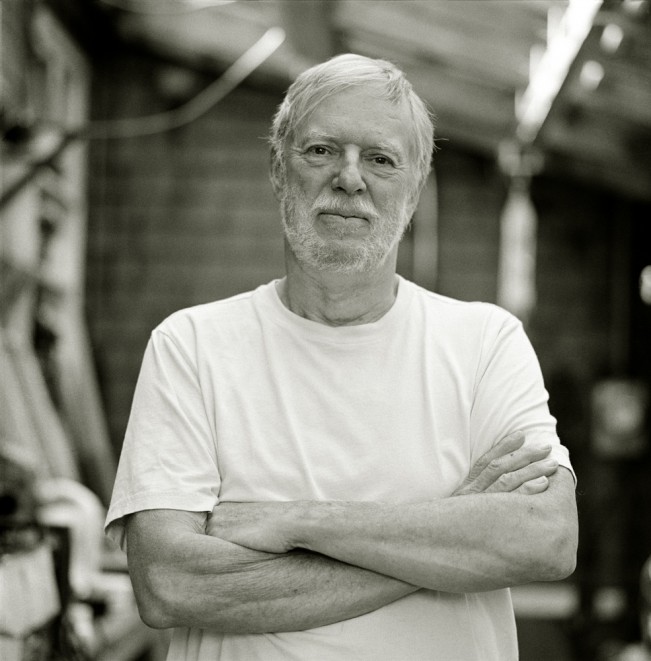

Richard Benson

Master Printer, Photographer, Distinguished Educator

Interviewed October 5, 2012, at his home and studio in Newport, Rhode Island

Silver is basically dead, and by God, it should be. It’s overdue. It was great while we had it. I think the digital capture is far superior on every level.

The speed of the transition, I think, has been remarkable. I think it’s happened for two reasons. One reason is the very rapid development of the new technology, and the other reason is the inability of the huge silver-based entities to adapt. I mean it’s quite astonishing that Agfa and Kodak both fell like mammoths being shot with a gun.

Technology is a wave front, and you can decide to get on that wave and surf it, or you can decide to bounce up and down in the water as the waves go by. And if you get up on the wave and surf it, you’re going to tumble half the time, but it’s going to be an exciting ride, and you’re going to go somewhere that the person doesn’t go who sits in the water in one place. The wave moves and the water doesn’t, and if you stay in the water, you just bob up and down like some old thing. So it’s always more interesting to me to get on that front of technology and go somewhere where we don’t know where we’re going. That’s what I’m really interested in.

Sally Mann

Photographer

Interviewed by Harvey Wang on November 23, 2012, at her home and studio in Lexington, Virginia

You pick your materials to suit your aesthetic and your vision. Sometimes it’s the other way around. Sometimes the process informs you what your vision really wants to be. I’ve had moments where I didn’t know what I was doing, but the film showed me, or the material showed me.

There is something about this (wet plate) process that’s a little more contemplative. And also, here’s another thing about these long exposures, something goes on with the eyes. There’s a certain sadness and depth that’s revealed in someone’s face, I think. You know you’re sort of sitting for the ages, and I don’t think an iPhone picture makes people think that they’re sitting for the ages.

Eugene Richards

Photographer

Interviewed January 4, 2013, at his home in Brooklyn, New York

Anyway, when all is said and done, what’s the point of complaining? Nothing will hold back the changes coming. The world is moving faster and faster, with exponentially more pictures being made, more often on cell phones and the like by nonprofessionals, with these pictures being transmitted and, in turn, devoured more and more quickly. If there’s an obvious cost to this, it’s the cost to old-fashioned storytelling, utilizing multiple pictures and points of view. Magazines, websites, online devices now tend to display not multiple images or stories, but single pictures that purportedly speak of life in a single glance. We want to look at things fast, want life thrown out in front of us in basic, graphic, attention-grabbing, quickly digested ways.

Susan Meiselas

Photographer, Filmmaker, Curator, Distinguished Educator

Interviewed June 13, 2012, at her home in New York City

I’ve been someone who embraces technology and enjoys exploring it, to figure out what it can do, along with what I can imagine. The question is, can you continue to invent a role where you belong? And maybe now I’m not quite sure where I belong anymore, both with my authoring, or even with the collective framing process—my collaborative process. That’s part of a complete reevaluation, crucial to do now.

If the iPhones are mostly the source of the billions of images we’re seeing uploaded daily, they’re mostly familiar subjects, friends and so on. Are the people who take these photos interested in other people’s perceptions? Whether or not you’re a “storyteller,” you’re making images. How interested are you in what the image is of? How is that image functioning in relation to a larger community? I don’t know what it means to just put things up into the ether of iCloud, Flickr, or whatever—storing life up there, instead of living life down here.

Paul Messier

Photograph Conservator

Interviewed by Harvey Wang April 27, 2011, at his conservation studio in Boston, Massachusetts

I think we’re at the end of an era, but that doesn’t really upset me at all. Imaging with light- sensitive materials is still going on. A charge-coupled device is a light-sensitive material just as a silver halide is a light-sensitive material. I think there is a lot of nostalgia right now in a way, looking back mournfully that we’re losing this, and I can relate to that. But it doesn’t bother me. What would bother me is if the knowledge of the materials was lost—if we lost the understanding of 20th-century photography, what it was to make a photograph in the 20th century. And what I’m trying to do is to preserve that knowledge. I think this is a really exciting period to care about photography, to watch it change. It’s kind of a privileged position to be in. I mean, arguably, we haven’t had a transition like this in the history of photography.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The Art of Documentary Photography: Rania MatarOctober 25th, 2025

-

Aiko Wakao Austin: What we inheritOctober 9th, 2025

-

Mara Magyarosi-Laytner: The Untended GardenOctober 8th, 2025

-

Diana Cheren Nygren: Mother EarthOctober 3rd, 2025

-

Joe Johnson: Sometimes Always NeverSeptember 3rd, 2025