Christopher Capozziello: Critical Mass Top 50: Living with Cerebral Palsy

This week Lenscratch is looking at some of the top 50 portfolios from Critical Mass….

Conneticut photographer, Christopher Capozziello, focuses on documenting both life around him, and stories that are outside of his own experiences. It’s important for him to tell the truth and his work has been recognized by World Press Photo, the Alexia Foundation, the Golden Light Awards, the National Headliner Awards, and the China International Press Photo Contest. His work is featured in a wide variety of publications including The New York Times, TIME, Newsweek, L’Express, The Dallas Morning News, and The Wall Street Journal. Christopher’s work is compelling, engaging, and incredibly moving.

The project he submitted to Critical Mass is Living with Cerebral Palsy and reflects his life with a twin brother who struggles with cerebral palsy.

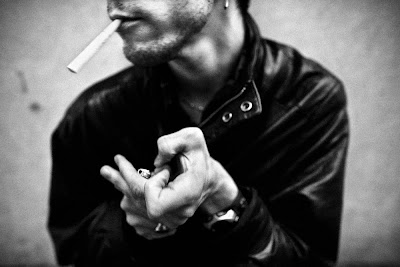

Initially, photographing my twin brother was not something I set out to do; but over the years, one picture has lead to another, and a story has emerged. The time I have spent photographing him has forced me to ask questions about suffering and faith, and why anyone is born with disease. Nick has Cerebral Palsy. Born with this neuromuscular disease, he is able to walk and speak and function on a fairly normal level, except for the fact that at any moment his muscles may spasm and cramp. When this occurs, his body becomes contorted, and he is unable to talk. A cramp may last minutes, or hours; sometimes his body is cramped for days. The pictures have been a way for me to deal with the reality of having a twin brother who struggles through life in ways that I do not. CP has kept Nick from many common things in life that most may take for granted: playing sports, holding a job, learning to drive, having a girlfriend.

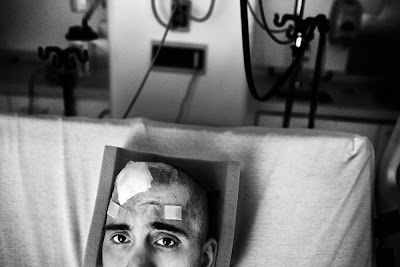

One of the hardest parts of being Nick’s twin is living my life, knowing that most of my experiences will forever be out of his grasp. Suffering raises countless questions. From time to time, someone will ask if I ever feel guilty for ending up the healthy one. I do. I look at him and think that it could have been me, and am constantly reminded and aware of his struggle. I wonder why he has to be the one who struggles on a moment-to-moment basis. It stirs up this process of grieving that never seems to end, like one long lament. Nick recently underwent Deep Brain Stimulation Surgery. For the first time in our family’s lives, we wait with great anticipation and hope that things will change for him. The doctors say that while the surgery may not completely stop his muscles from cramping, it may significantly decrease the effects of the cramps on his body. Already, Nick has seen improvement, lifting everyone’s hopes and expectations.

The pictures have been a way for me to deal with the reality of having a twin brother who struggles through life in ways that I do not. CP has kept Nick from many common things in life that most may take for granted: playing sports, holding a job, learning to drive, having a girlfriend. One of the hardest parts of being Nick’s twin is living my life, knowing that most of my experiences will forever be out of his grasp. Suffering raises countless questions. From time to time, someone will ask if I ever feel guilty for ending up the healthy one. I do. I look at him and think that it could have been me, and am constantly reminded and aware of his struggle.

I wonder why he has to be the one who struggles on a moment-to-moment basis. It stirs up this process of grieving that never seems to end, like one long lament. Nick recently underwent Deep Brain Stimulation Surgery. For the first time in our family’s lives, we wait with great anticipation and hope that things will change for him. The doctors say that while the surgery may not completely stop his muscles from cramping, it may significantly decrease the effects of the cramps on his body. Already, Nick has seen improvement, lifting everyone’s hopes and expectations.

Christopher also recently won the Berenice Abbott Prize for an Emerging Photographer through the Julia Dean Workshops in Los Angeles.

When I make pictures, I ask the permission of others to be allowed into their lives– to observe, and to ask questions – in order to learn and understand somethingthat is outside of my own experience. Sometimes, however, photographs are made that offer little understanding. Sometimes we walk away with questions that offer no answers. The more time I spend with Klansmen, Klanswomen, and their families, the more I find myself with the unanswered questions of why these specific people continue on in a course of segregation and hatred. And sometimes, in rare moments, someone in front of my lens begins to open up in ways that can give us a glimpse into answering these “Why” questions.

When I first began photographing members of the Klan, the question I came to them with is, “What is the real reason you believe in segregation, or racial superiority, or discrimination?” The problem with asking that question, is that we often do not truly understand why we do the things we do; often we cannot even deal with the reality of why we believe what we believe. It is always because of something else. Something deeper. Something behind it all.

One summer night, in 2002, after hours of interviewing, I turned off my tape recorder and stopped asking questions of David, a young member of the Klan. He lay on the hood of his car outside a trailer, and, looking up at the night sky, he explained to me that two black men murdered his mother in 1992, when he was only twelve years old. His voice was hard when he told me this, but not angry. She was a taxicab company owner, and they robbed her, getting away with only $17. I had just spent hours with him, asking him questions about why he was involved, how he had become a Klansman, what he believed, and I had come no where near this. It seemed David had a reason to turn to something so dark, yet it was a reason he could not even vocalize.

Earlier that same night, while explaining to me how the Klan justifies what they believe, David quoted John 3:16

“For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life.”

I told him about a close friend of mine, who was a Christian, and an African-American man. I wanted to know if he would not be permitted eternal life based on that scripture, because he was black. David paused a moment and said he had never thought about it that way before. He said, based on the scripture, he thought my friend would have eternal life.

A couple of months later, I received an email from David, and he said that, based on my questions and our conversations, he began to feel that the Klan had it wrong, and that he had decided to leave. All of this, because I was just doing what I was supposed to do: ask questions.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Lorraine Turci: The Resilience of the CrowMarch 16th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Awards: Natalia Garbu: Moldova LookbookMarch 15th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Rayito Flores Pelcastre: Chirping of CricketsMarch 14th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Alena Grom: Stolen SpringMarch 13th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Louise Amelie: What Does Migration Mean for those who Stay BehindMarch 12th, 2024