Bill Miller

Bill Miller became preoccupied with photography when he attended high school in Manhattan, but I think he was studying painting with Clyfford Still in another lifetime. Bill’s stunning Broken Polaroids images don’t necessarily reflect his rich photographic roots; He graduated from Bard College where he studied photography with Larry Fink and Stephen Shore. He’s been a photojournalist and documentary photographer ever since then and has worked with Saveur, Harpers, Paris Match, Spin, GQ, Stern, The Globe and Mail, the NY Daily News, as well as organizations such as Doctor’s Without Borders, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Human Rights Watch and he’s been a photographer for the New York Post for close to 10 years.

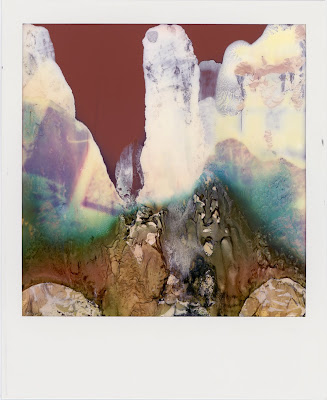

Broken Polaroids: These pictures are taken with a camera that is, by most definitions, broken. I found an old Polaroid SX-70 camera under a pile of junk at a yard sale last summer. I’ve always loved this camera for its weird, mysterious, and enchanting qualities. It is an ingeniously conceived, complicated bundle of gears and switches with hundreds of moving parts packed in tight like a chrome and leather pistol. As digital cameras become smaller and quieter with no moving parts, the Polaroid with its noisy engine, gears, and rubber bellows seems increasingly charming and archaic to me. What was a cutting edge technology in 1972 is now teetering on the edge of extinction.

With its first use I realized the camera wasn’t functioning properly. It sometimes spills out 2 pictures at a time and the film often gets stuck in the gears, exposing and mangling the images in unpredictable ways. This is common with Polaroids. I’ve been shooting this SX-70 film my whole life and from my experience at least 5% of the time the images fail for one reason or another. Over time you stop noticing. The failed Polaroids are discarded with the packaging, a statistical casualty of such a complicated mechanism. It was only when my statistical casualties jumped to nearly 100% that I realized that even against my will, this camera was making, totally by chance, some interesting, and occasionally beautiful pictures. It’s this kind of unpredictability that makes old cameras and processes appealing and it wasn’t until I noticed what was happening that I started saving them. I must have thrown out scores of ruined Polaroids over the years. Millions of happy accidents have probably been discarded, unappreciated over the last few decades around the world.

As my SX-70 became more eccentric the film showed less and less of what was in front of the lens. Yet out of habit or instinct or lack of common sense I kept pointing it at things. “It’s a camera, after all. Isn’t it?” I thought, even though it appeared to be totally indifferent to the objects I focused on. Maybe it’s a camera that was dropped on its head, got amnesia and became a photographic painting machine.

Either way, I was impressed with the old technology’s resilience and before long I was participating in its process, collaborating with it. Over time I’ve figured out how to control and accentuate aspects of the camera’s flaws but the images themselves are always a surprise. Each one is determined by the idiosyncrasies of the film and the camera.

I found that when I was looking at the prints I couldn’t get close enough, not with my eye, not with a lupe. So I started scanning them at high resolutions so I could see what wasn’t readily viewable. What I found was a rich variety of color texture made from crumpled and stressed emulsion inside the Polaroids, reminiscent of topographical landscapes. I used huge files (600mb) to make 30×36 in prints where these details could be seen. I kept the classic Polaroid white border to give a sense of its scale.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Month: Photographers on Photographers, Dennis DeHart in conversation with Laura PlagemanApril 16th, 2024

-

Luther Price: New Utopia and Light Fracture Presented by VSW PressApril 7th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Eren SulamaciMarch 27th, 2024

-

European Week: Sayuri IchidaMarch 8th, 2024

-

European Week: Jaume LlorensMarch 7th, 2024