Photographers Of Color: Aaron Turner: Arkansas

Since the beginning of my photo journey, I have thought a lot about the community in which I make work. When I first started out, I was aware that women had a way to go – a male centrist climate was shaping the kind of work that made it on to museum and gallery walls. I remember a conference where out of several hundred attendees only three women were in attendance – I was one of those three. Over the years the statistics have changed significantly, but now when I survey the photo landscape, I wonder, where are the photographic artists of color? I know am not the only person asking this question. Our community is hungry for other voices, other points of view, and different narratives. I have attended numerous photo festivals and portfolio review events, and I can count on one hand the number of photographers of color in attendance. And because those events are where I often find work to feature on LENSCRATCH, this limits the range of work I show, which has long been a frustration.

To shift this paradigm, I reached out to photographer Aaron Turner, who curates the Twitter site Photographers of Color, and asked for his help. Going forward, several times a year on LENSCRATCH, Aaron will feature posts on photographers of color (beyond the voices we already feature), bringing into focus a richer photographic community with more diverse voices and visions. Today on LENSCRATCH, we share his project, Arkansas, along with an insightful interview. I am grateful for his participation and insights and look forward to discovering new artists.

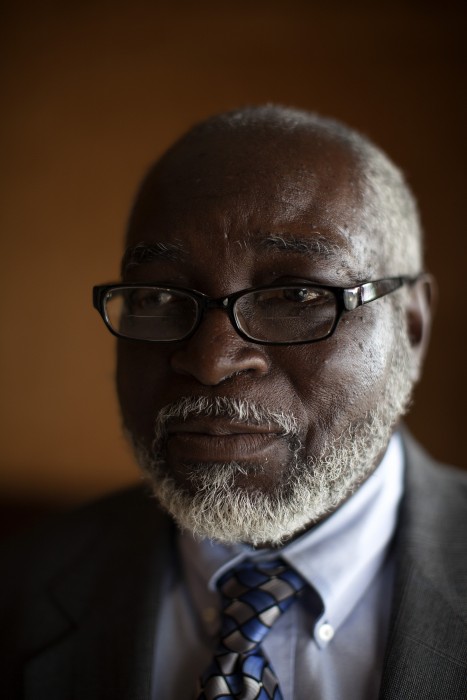

Aaron Turner (b.1990) is a photographer and educator currently based in the Hudson Valley working as Technical Director in the Film and Electronic Arts Department at Bard College. He uses photography to pursue personal stories of people of color, in two main areas of the U.S., the Arkansas and Mississippi Deltas. Aaron has a deep interest in the role that documentary photography plays in both the art and journalism worlds and the crossover this creates in contemporary photography. He recently graduated from the Mason Gross School of Art at Rutgers University with his MFA.

Arkansas

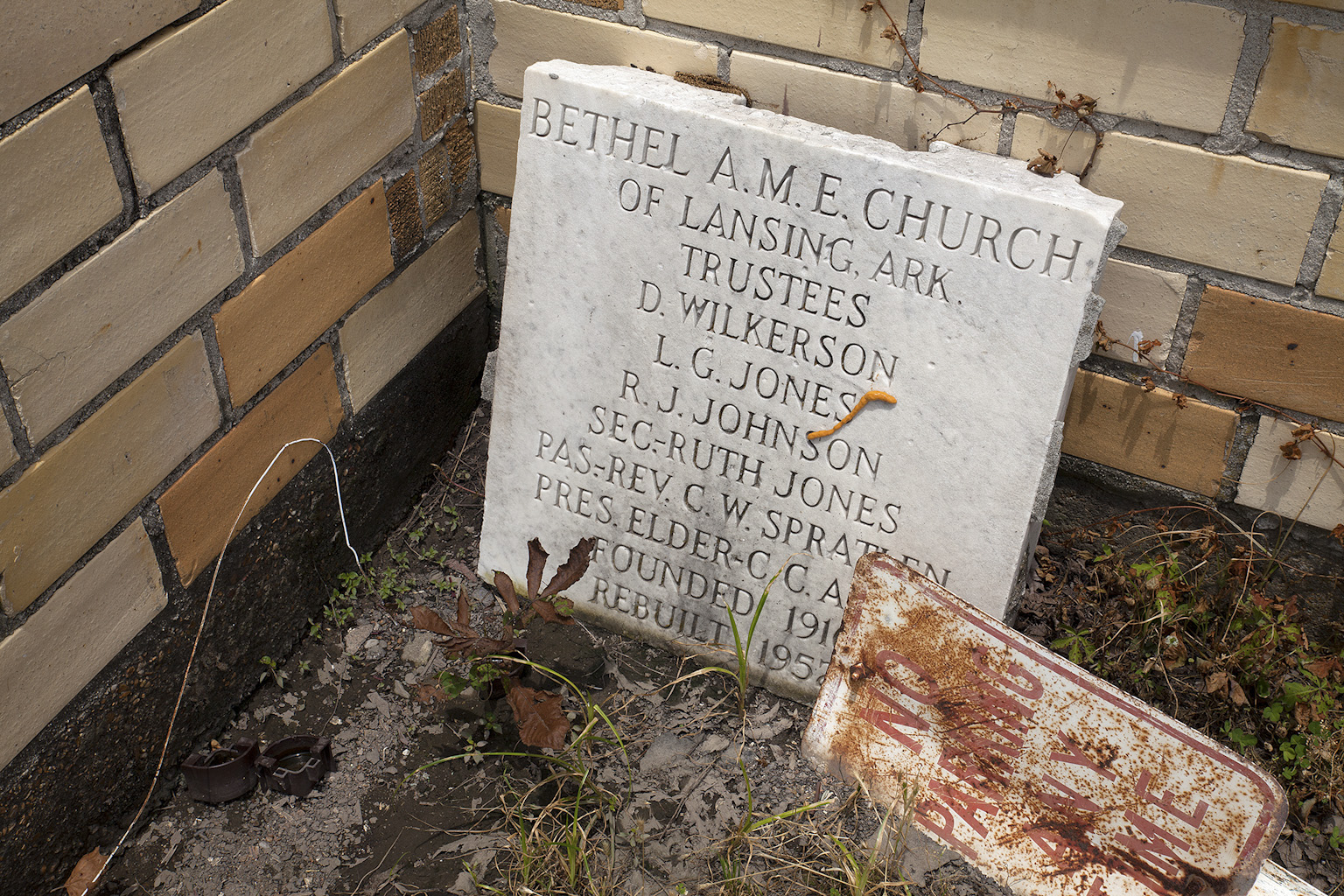

The Arkansas Delta is not only a series of river basins that empty into the Mississippi from the west but also a conglomerate of cultural richness which consists of farming, religion, music, and food to name a few. During the 70s and 80s the fading of sharecropping and technological advancements in farming equipment caused major shifts in farming and other local industries, resulting in people looking elsewhere for work. Photographer Eugene Richards photographed the Delta 40 years ago in the late 60s and early 70s. The landscape of the Arkansas Delta has remained the same but the people who inhabit it have shifted dramatically, through population loss. My project, Home: The Arkansas Delta, looks at complex remnants of the region tradition, population loss, sharecropping, king cotton, my own family and many other topics in between. Growing up in the Arkansas Delta in a small town called West Memphis, and looking back on things, resilience has always been deeply rooted in those around me. My approach to documenting the region is through photography to capture the resilience of people and the region itself, from an insider’s perspective. I use photographs as a visual representation to talk about the present and future while comparing it to the past. I want to share the story of my own family within a larger context of the region itself.

Aaron, can you tell us a bit about yourself and what brought you to photography?

Well, I grew up in a town called West Memphis, Arkansas located on the edge of the Delta across the Mississippi River from Memphis, Tennessee (in a tri-state region of Arkansas, Mississippi, and Tennessee). I first got into photography from a journalistic approach because I was majoring in journalism at the University of Memphis. I wanted to add taking photos to my writing skills for newspapers (this was around the time everyone was being laid off from papers and being able to do it all was being heavily emphasized), but one day in class my professor showed Robert Capas photos from Normandy Beach, from that day forward I wanted to be a photojournalist, a war photographer even. They didn’t have photojournalism as a major at University of Memphis so I decided to go to Ohio University for their master’s program in Visual Communications. This was my first broad experience with photography, and overall this experience further got me interested in photography as a whole.

I felt like I was only getting one side of the story in a way. There had to other reasons people were making photographs other than for a newspaper, this is why I decided to attend Mason Gross School of the Art at Rutgers University; to get a different perspective. I’ve always been interested in what people outside of photography think about images. This program exposed me to painting, sculpture, performance, video, and art in a broad context. It was an interesting two years there for sure.

As a black man, how do you see the current photography landscape and your place in it?

I see myself in the current landscape of photography, as a black man, in two very opposite ways: The first being that my skin color doesn’t matter and that all I need to do is hustle, continue getting better at photography, make the connections, and generate solid ideas to make work about. I’ve had other photographers of color tell me this about the photo world and myself and my work; it pops up every now and then. Secondly, I can see the photo worlds landscape as there only being a select few people who look like me, that are really achieving a major level in the photo world, but there is a gap amongst the emerging to mid-career artists. And even sometime, those who don’t look like me achieve success – photographing people who look like me. I’ve gone to the New York Times Portfolio three times now, once to be reviewed and twice as a volunteer, each time I meet some of the best photographers of color currently making work, and many of them have or recently started to achieve at a very successful level. But compared to the larger scheme, there are always more people out there. I think photography is one of those professions where you really have to put in the time and wait your turn in line, and it depends on what you’re doing, why you’re doing it, and sometimes where you’re doing it, determines how long you wait.

What made you begin to curate Photographers of Color on Twitter?

What made me begin Photogs of Color on Twitter were a few personal experiences along with spending a lot of time trying to find other photogs of color who often sit outside the mainstream of the photo world. I started to realize we all didn’t know about each other and that’s why I wanted a place to connect everyone as best as I could, so everyone could see each other’s work. I know I still haven’t found all current photographers of color currently making work whether they are in school or out of school, and not everyone is on Twitter. But, I’m just slowly trying to amass as many projects and people on that Twitter page as I can.

Why do you think we don’t see more work celebrated by photographers of color? Certainly, there are stellar image makers that have garnered much attention, but what about the emerging to mid-career artists?

This question makes me think about Kerry James Marshall, a Chicago based painter who is African American. He talks about the work that black artists make and often times the topics of that work will be viewed as marginalized and quickly written off. People may say, hey, the work is out of date, it’s not up to par, and it’s not referencing anything in art history etc…

I encourage everyone to go hear him speak whenever you can and also listen to one of his many talks online. From listening to him talk, one of the ways he approached making work was to know what they know. The they being the people who write about art, the curators at the big museums, etc. He sought to have the same level of understanding of art and art history as they did and that affected the way he made his paintings. All of his paintings have a black figure in them, because his goal was to make viewers aware and used to seeing a black figure in a museum, where it’s most likely not going to be (or is) seen.

With all that being said, I think that the powers that be in the photo world sometimes may not even see work made by photographers of color, and when they do, if the work happens to be on a subject of race or anything related to it, or if it’s not of a certain style then it has the greater chance to be written off.

As photographers of color, let’s know what they know, let’s know as much as you can about the history of photography, the business side of things editorial or gallery, know how to market your work, how to network, strategize, use the strength of numbers, put money together to rent out a space and show as a collective, but do all these things to the best of your ability and in the most professional way possible.

As far as the emerging to mid-career artist, I would say get your work exposed to a broader audience in traditional ways: magazines in print and online, galleries, museums. Those arenas will mainly be dominated by those who already have made a name for themselves, but think about achieving at the highest level. There are many routes and avenues these days to get your work out– everyone is making books and if you bring a level of excellence to it’s presentation and your project is unique enough, it will grant you a lot of success in different ways. But again I would say there is strength in numbers: get together, present as best you can, and get people to pay attention.

What can our community do to change things? How can we broaden our exposure?

I don’t think that photographers of color are necessarily being deliberately ignored; I would say that it’s more like the second question here, what’s the rate of exposure? And also what’s the expectation, if the most famous photographer of color you know is Carrie Mae Weems and you expect all photographers of color to look like hers, well she already has that style sort of locked in, she’s already done it, so how does one who’s interested in the same things as Weems make it different than she did and always contribute to the conversation of photography in a profound way. If you don’t consider these things carefully you can get caught up in a comparison game and the work is at a stand still.

Ways people can broaden their exposure is by following Photographers of Color on Twitter, also Qiana Mestrich, Strange Fire Collective, John Edwin Mason, Mark Speltz, Dr. Debora Willis, there are some many more. But if you want more exposure to the modern and historical topics dealing with photographers of color, you’ll find among these names here.

Let’s talk about your own work. We are going to feature your Arkansas work on Lenscratch today, but first I’d like to focus on your series Isolated Truths. In setting out to learn about the Underground Railroad in Southeastern Ohio (Appalachia), you discovered something more complicated about the African American communities that surround the area. Can you share that discovery?

Yes indeed, it’s a complicated discovery and a project that I plan on continuing in the future. I was living in Appalachia for the first time, but I always had an obsessive type of wondering about what makes up Appalachia. And of course I was interested in discovering black communities in Appalachia. Everything that sort of promotes, and brands Appalachia is certainly not a black face or identities, you just don’t see it. But I knew that there had to be black communities surrounding Athens, Ohio where I was living.

After reaching out to a few elders in the area I got the lay of the land but also what things like the Trail of Tears and the Under Ground Railroad helped shift and make up the current racial make up of the area.

There are people known as Melungeon throughout Appalachia but I think that’s more of a derogatory term to some, you have to be careful how you address people depending on where you are in the region. Each community identifies in different ways. Melungeon is a way of saying my genealogical makeup is White, Indian, and Negro or WIN, some identify as person of color, some people look white and identify as black, some people’s parents look white but they are of a darker complexion and so on. This mixture is said to come from people being mixed before they even migrated to America, from Indians who hid out and escaped during the Trial of Tears, Free black who settled in the area, Slaves who came through the Underground Rail Road (which most of continued on to Canada), and you average Dutch, Irish etc… who settled in the area. There were a lot of mixed communities who cohabitated with one another and there was no friction, they accepted each other.

Fast forward to now , it’s still going on and even more complex, but when you talk to the people I photographed, it’s just who they are, they don’t necessarily carry in around on their sleeves, there is a lot of tension still boiling over from slavery and segregation, and people just want to move on with their lives and live in peace. The Klan is still active in this part of Ohio and there are known sun down towns, if you’re of a certain racial make up, it’s encouraged that you don’t remain in that area after sundown. Now it’s not anything too crazy I would think but I’m also not totally sure because things still operate on a more covert level now in these really small communities.

Did the discovery shift your historical thinking?

It never really shifted my historical thinking on race but more so the specifics of how it happened in this specific region. It’s in my own family so I was always aware of it when my dad and granddad shared the family history with me all the way back to our ancestors who were enslaved and the family who owned them back to England. In both my mom and dads family there is a mixture of races but the specificity around if is very vague because it’s not something people wanted to talk about in those days especially. But I can see in how people within my family look and in old family photos, it’s there.

I read a book called Passing by Nella Larson as an undergrad student, and that has informed what I’ve been interested in as far as photography since then. The main character in the book during a time of segregation struggled with being able to pass for white and enjoy a better life and having to disown her mother who was visibly black and disowning herself as a black person. This topic still affects many people today, and it’s very relevant, this still very much affects people in their everyday life even today.

Your MFA thesis project is much more conceptual than the rest of your work—is this a new direction for you?

Yes, this work from my thesis is a new direction ascetically, but at the heart of the work it’s still trying to talk about and deal with issues of race. It’s deliberately black and white for that reason, but abstract so that the viewer can experience it in a different way than usual. It’s very much motivated by Nella Larson’s book Passing and historical artifacts that deal with race. I’m experimenting with talking about race through abstraction, and why black artists use it to talk about race. There are many more people who came before me back then and even now in this modern era who are making work from a similar standpoint. My whole approach was to critique making work about being black as a black artist in the assumption that most people who would view my work would not be black. I make the work that I do because I want to see why people think the way they do about race, not necessarily to script a specific narrative but to see why that narrative exist.

What have been some of your artistic influences?

I would say my two main influences have been Hank Willis Thomas and again Kerry James Marshall. Hank Willis Thomas’ work is so blunt and people kept telling me you can’t make work like that, but I saw his work and he was doing just that in many cases. The challenge to myself was to find out why he was choosing those things ascetically and the ideas behind them.

Marshall’s ideas about art just appeal to me in such a powerful way; I could talk about him in the length of an entire interview that how much his work influences me even though he is a painter.

I also like Barbara Kasten and Leslie Hewitt, Gordon Parks, William Eggleston, Glen Ligon, and David Hammons.

Your series, Arkansas, is about memory and growing up. Can you tell us how you got started on this project?

I got started on this project as a class assignment. When I was at Ohio University we had a class called Magazine where we had to go out and shoot in the field for ten days, gather content and comeback to create our own publication. I was living far away from home for the first time at this point and to sort of cope with that I thought of home a lot and family memories were on my mind more than usual than they had been my entire life. So I decided let me go home and attempt to capture this feeling and memory I was having about home. I saw Eugene Richards work about the Arkansas Delta and saw he made pictures in my hometown of West Memphis, Ark, that was a turning point because I said, well I definitely need to go back and make pictures in that area too, being from there and all. The area is still in transition; people are still leaving the area and looking for work. Farming in the area is just not what it used to be, even though a few people are still doing well at it. Most of my family has moved from the area including myself; my Dad still lives there. So my intent for this project is to continue working on it, meeting with family still there and trying to meet people who still remain and capture my own memories of going to church, the rural areas, food, and music through them.

The portraits in the project are quite exceptional—are those captured with a 4×5?

The portraits in this project are not 4×5 but I wish they where. Everything is taken with my Canon 5D Mark II, although the work form my thesis is all 4×5. I plan on using different formats as I continue to go back to the area, just to changed things up and give my self a different way of seeing things I may have missed.

What did you learn about yourself in creating this project?

Doing this project and continuing to work on it I learned that everything about growing up in this part of Arkansas made me who I am, and that I’ll always keep going back. Hopeful live permanently again one day. It’s hard to explain in words, it’s mostly a feeling, but I hope that the photos I take help capture a little bit of that at least.

What’s next for you?

I just moved to the Hudson Valley in New York. I took a job at Bard College. I don’t know how long I’ll be here but it’s where I am for now. I’m just going to work on small projects in this area, and continue making the thesis work I started and keep going back to Arkansas when I can. I have some plans to make a few small book editions in the next year or two, so hopefully that keeps me busy until the next thing comes around.

And finally, describe your perfect day.

A perfect day for me is sort of hard to pin point because everyday isn’t perfect, but I would say on average my week includes several elements that would make up a perfect day for me personally. Things like a good meal at lunch or dinner, then being able to get work stuff out of the way early. Something photo related but it doesn’t have to be actually photographing, I stopped photographing everyday from a serious mindset for a few years now, I just like to try and enjoy things first without photography, but I’m always seeing pictures, especially when I’m just out and about walking around.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Ian van Coller: Naturalists of the Long NowApril 22nd, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Tyler Green in Conversation with Megan JacobsApril 15th, 2024

-

Shari Yantra Marcacci: All My Heart is in EclipseApril 14th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Cansu YildiranMarch 29th, 2024

-

Broad Strokes III: Joan Haseltine: The Girl Who Escaped and Other StoriesMarch 9th, 2024